April 20, 2004

Generational changes: decline or progress?

A few days ago, I complained about the lack of evidence for Camille Paglia's claim that "Interest in and patience with long, complex books and poems have alarmingly diminished", and that today's students "cannot sense context and thus become passive to the world, which they do not see as an arena for action". I hope that some of the people who really know about this sort of thing will eventually post an annotated guide to the literature on these questions.

Meanwhile, I've done a bit of poking around. I haven't been able to find anything that directly measures changing "interest in and patience with long, complex books" or ability to "sense context" over the past few decades. However, I can point to a couple of well-known trends that seem somewhat relevant, one of which has been heading steadily up for a century (the "Flynn effect" in IQ tests), while the other is now flat after pointing down for a couple of decades (U.S. verbal SAT scores). In neither case does it seem likely that TV, PCs and video games are responsible for (much of) the change.

The "Flynn effect", which is named for a social scientist named James Flynn who first discovered it about 20 years ago, involves "an average increase of over three IQ points per decade ... for virtually every type of intelligence test, delivered to virtually every type of group."

"For one type of test, Raven's Progressive Matrices, Flynn found data that spanned a complete century. He concluded that someone who scored among the best 10% a hundred years ago, would nowadays be categorized among the 5% weakest. That means that someone who would be considered bright a century ago, should now be considered a moron!"

There is a great deal of controversy about whether these changes are "real", what causes them, and what they might mean. The increases seem to be accelerating, to the extent that it is possible to measure rates accurately enough to tell. Though all aspects of all types of tests are affected, "the increase is most striking for tests measuring the ability to recognize abstract, non-verbal patterns. Tests emphasizing traditional school knowledge show much less progress."

On the other hand, there was a significant decline in SAT verbal scores in the U.S. from the early 60s through the late 70s, when the scores leveled out.

It seems even less clear in this case what is going on. Here is an ETS document about SAT norming. It seems that some but not all of the change can be attributed to demographic changes in the population of students taking the test. The residual effects have variously been attributed to changes in educational standards; to the effects of television; to 1960s cultural mindrot; and so on.

One of the more interesting of these arguments is presented in a paper entitled "Schoolbook simplification and its relation to the decline in SAT-verbal scores", by Donald Hayes, Loreen Wolfer and Michael Wolfe (American Educational Research Journal. 33(2), 1996, pp. 489-508). Here's the abstract:

Argues that the 50+ point decline in mean SAT-verbal scores between 1963 and 1979 may be attributed to the pervasive decline in the difficulty of schoolbooks found by analyzing the texts of 800 elementary, middle, and high school books published between 1919-1991. When this text simplification series is linked to the SAT verbal series, there is a general fit for the 3 major periods: before, during, and after the decline. Long-term exposure to simpler texts may induce a cumulating deficit in the breadth and depth of domain-specific knowledge, lowering reading comprehension and verbal achievement. The two time series are so sufficiently linked that the cumulating knowledge deficit hypothesis may be a major explanation for the changes in verbal achievement. A simple, low-cost experiment is described that schools can use to test how schoolbook difficulty affects their students' verbal achievement levels.

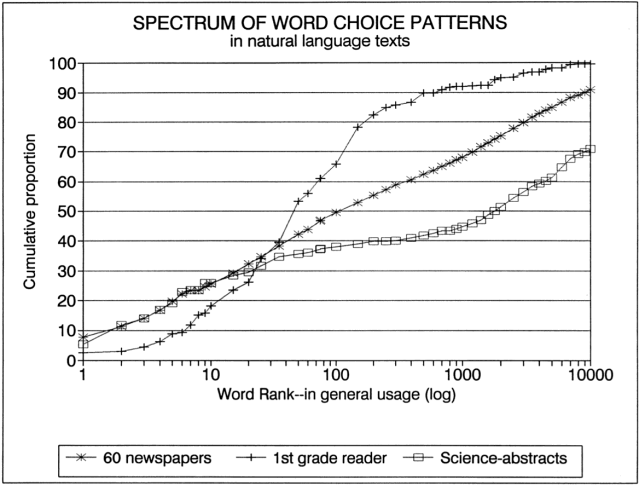

You can learn more about the measures of text difficulty used, and download software for doing the calculations as well as spreadsheets with all the raw text-difficulty data, from Donald Hayes' web site at Cornell. Hayes' text complexity measure is entirely lexical -- it depends only on the frequency distribution of the words in a text. The general idea is illustrated in the figure below, which compares the distributions for a large newspaper corpus with a first-grade reader (which uses fewer rare words) and a set of scientific abstracts (which use a larger proportion of rare words).

It's a bit unexpected not to include any measures of syntactic complexity -- even something as simple as mean sentence length. However, anyone who has looked a collection of historical schoolbooks quickly gets the impression that they have gotten simpler over time, and it's nice to see that Hayes is able to document this using purely lexical measures.

[Thanks to Mark Seidenberg for a pointer to Hayes' web site]

Posted by Mark Liberman at April 20, 2004 12:14 AM