September 09, 2004

Type like a pirate day

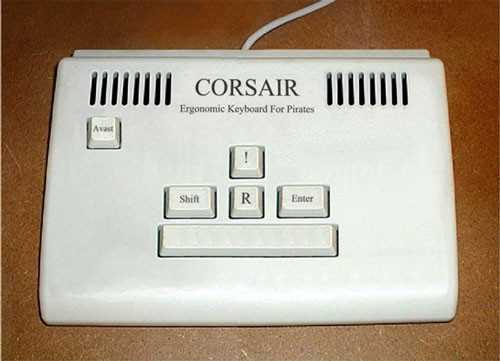

It's only nine days until Talk like a Pirate Day. Linguists know that talking is primary, but blogging is mainly a textual form, so some of you may want to Type Like a Pirate instead, using your trusty old Corsair ergonomic keyboard:

The link I used when I blogged this last fall is dead. There are lots of copies out there on the net, including this one from 9/19/2003, but I don't know who's the original creative force responsible for this picture. If someone will tell me (myl at cis.upenn.edu) I'll give a proper attribution.

Pop-culture kitsch aside, real pirates were (and still are) a pretty reprehensible group. One particular set of pirates played an important role in the early history of the United States: the Barbary Pirates, who operated with (city-)state support out of Tripoli, Tunis, Morocco and Algiers. After an independent United States lost the protection of the British government -- which paid subsidies or tribute to the pirates as protection money -- U.S. shipping was at risk, and Congress allocated $80,000 as tribute in 1784. However, in 1785, two American ships were captured by the Algerians, who asked for $60,000 in ransom for their crews. An on-going sequence of threats, tribute and ransoms eventually led to nearly 15 years of intermittent war.

An interesting discussion of this history, written by Gerald Gawalt, the manuscript specialist for early American history in the Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, can be found here. Some quotes are below:

In his autobiography Jefferson wrote that in 1785 and 1786 he unsuccessfully "endeavored to form an association of the powers subject to habitual depredation from them. I accordingly prepared, and proposed to their ministers at Paris, for consultation with their governments, articles of a special confederation."... "Portugal, Naples, the two Sicilies, Venice, Malta, Denmark and Sweden were favorably disposed to such an association," Jefferson remembered, but there were "apprehensions" that England and France would follow their own paths, "and so it fell through."

Paying the ransom would only lead to further demands, Jefferson argued in letters to future presidents John Adams, then America's minister to Great Britain, and James Monroe, then a member of Congress. As Jefferson wrote to Adams in a July 11, 1786, letter, "I acknolege [sic] I very early thought it would be best to effect a peace thro' the medium of war." ... "From what I learn from the temper of my countrymen and their tenaciousness of their money," Jefferson added in a December 26, 1786, letter to the president of Yale College, Ezra Stiles, "it will be more easy to raise ships and men to fight these pirates into reason, than money to bribe them."

Jefferson's plan for an international coalition foundered on the shoals of indifference and a belief that it was cheaper to pay the tribute than fight a war. The United States's relations with the Barbary states continued to revolve around negotiations for ransom of American ships and sailors and the payment of annual tributes or gifts. Even though Secretary of State Jefferson declared to Thomas Barclay, American consul to Morocco, in a May 13, 1791, letter of instructions for a new treaty with Morocco that it is "lastly our determination to prefer war in all cases to tribute under any form, and to any people whatever," the United States continued to negotiate for cash settlements. In 1795 alone the United States was forced to pay nearly a million dollars in cash, naval stores, and a frigate to ransom 115 sailors from the dey of Algiers. Annual gifts were settled by treaty on Algiers, Morocco, Tunis, and Tripoli.

When Jefferson became president in 1801 he refused to accede to Tripoli's demands for an immediate payment of $225,000 and an annual payment of $25,000. The pasha of Tripoli then declared war on the United States. Although as secretary of state and vice president he had opposed developing an American navy capable of anything more than coastal defense, President Jefferson dispatched a squadron of naval vessels to the Mediterranean. As he declared in his first annual message to Congress: "To this state of general peace with which we have been blessed, one only exception exists. Tripoli, the least considerable of the Barbary States, had come forward with demands unfounded either in right or in compact, and had permitted itself to denounce war, on our failure to comply before a given day. The style of the demand admitted but one answer. I sent a small squadron of frigates into the Mediterranean. . . ."

The American show of force quickly awed Tunis and Algiers into breaking their alliance with Tripoli. The humiliating loss of the frigate Philadelphia and the capture of her captain and crew in Tripoli in 1803, criticism from his political opponents, and even opposition within his own cabinet did not deter Jefferson from his chosen course during four years of war. ... Jefferson was able to report in his sixth annual message to Congress in December 1806 that in addition to the successful completion of the Lewis and Clark expedition, "The states on the coast of Barbary seem generally disposed at present to respect our peace and friendship."

In fact, it was not until the second war with Algiers, in 1815, that naval victories by Commodores William Bainbridge and Stephen Decatur led to treaties ending all tribute payments by the United States. European nations continued annual payments until the 1830s.

[Update: more here.]

Posted by Mark Liberman at September 9, 2004 08:49 AM