October 04, 2006

Terroir alert

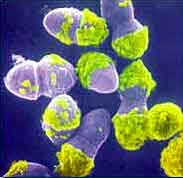

In the cheese business, the terroirists are winning. In Britain, they've gotten a phonetician to vouch for the local dialects of cows. Here in the U.S., they're focusing on local molds and bacteria. Well, they try not to mention the bacteria -- they use the term microflora, with an occasional tasteful presentation of the word "mold" as if it were a species of flower.

In the cheese business, the terroirists are winning. In Britain, they've gotten a phonetician to vouch for the local dialects of cows. Here in the U.S., they're focusing on local molds and bacteria. Well, they try not to mention the bacteria -- they use the term microflora, with an occasional tasteful presentation of the word "mold" as if it were a species of flower.

In today's NYT ("The Earth is the Finishing Touch"), the reporter, Marian Burros, lists all the types of wee beasties involved:

As cheesemaking and the appreciation of good cheese have matured in the United States in the past few years, American cheesemakers have begun to better understand the place of microflora — bacteria, yeast, molds — in the process of aging cheese. In these new caves and cellars, cheeses are exposed to an array of the tiny organisms local to the area.

But the word "bacteria" seems to be avoided in the quotes from cheese people:

By going underground, Mary and David Falk have stayed on top of most artisanal cheesemakers in this country.

For 10 years, at their Love Tree Farmstead in Grantsburg, Wis., they have been aging cheeses in caves dug into a hillside, their concrete walls painted with pictographs. The Falks say it’s the only way to produce deeply flavored, nuanced, natural-rind tommes and wheels like those of European cheesemakers.

“We believe in fresh-air aging, pollens, molds, humidity,” Ms. Falk said. “And we’ve positioned our cave so that it is surrounded by a wildlife refuge. It’s really a head trip to see semis pull up in the woods to get the cheese. It’s like from ‘The Twilight Zone.’ We wanted something that worked on the natural rhythm of the area. We took the microflora from what was there; we get humidity from the springs.”

Mary Falk waxes lyrical about the mold:

Ms. Falk describes the mold that forms on cheese as “a miniature flower garden, with the flowers sucking air into the cheese and pulling out the gas, and every little mold having its own little flavor profile.”

Jeff Roberts, author of the forthcoming Atlas of American Artisan Cheese, sticks with the formal and neutral "microflora", adding the all-purpose positive word "community" to make it clear that no disrespect is intended:

“Caves are not only great in terms of maintaining temperature and humidity but they also reflect the unique microflora communities,” Mr. Roberts said. “The microflora interacts with cheese; the cheese obtains a certain level of quality and so does the microflora. The cheese evolves over time and you can’t regulate it. It has a powerful connection to place.”

The complexity of the bacterial contribution to this process (whether in a warehouse or in a cave) is indicated by this abstract (M. Morea, F. Baruzzi and P.S. Cocconcelli, "Molecular and physiological characterization of dominant bacterial populations in traditional Mozzarella cheese processing", Journal of Applied Microbiology 87 574, 1999:

The development of the dominant bacterial populations during traditional Mozzarella cheese production was investigated using physiological analyses and molecular techniques for strain typing and taxonomic identification. Analysis of RAPD fingerprints revealed that the dominant bacterial community was composed of 25 different biotypes, and the sequence analysis of 16S rDNA demonstrated that the isolated strains belonged to Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. mesenteroides, Leuc. lactis, Streptococcus thermophilus, Strep. bovis, Strep. uberis, Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis, L. garviae, Carnobacterium divergens, C. piscicola, Aerococcus viridans, Staphylococcus carnosus, Staph. epidermidis, Enterococcus faecalis, Ent. sulphureus and Enterococcus spp. The bacterial populations were characterized for their physiological properties. Two strains, belonging to Strep. thermophilus and L. lactis subsp. lactis, were the most acidifying; the L. lactis subsp. lactis strain was also proteolytic and eight strains were positive to citrate fermentation.

You can learn a lot more about this by asking Google Scholar about {cheese fermentation} or {cheese bacteria}.

Rhetorical exercise for the day: write a description of bacterial fermentation in cheese that's as appetizing as Mary Falk's prose poem about the molds ("a miniature flower garden, with the flowers sucking air into the cheese and pulling out the gas, and every little mold having its own little flavor profile").

Memo to the artisanal cheese industry: if you need expert linguistic advice, for example about the analysis of bacterial discourse, I'm available to consult. I try to set out an interesting sampling of artisanal cheeses at Tuesday night study breaks in the college house at Penn where I live, and I could use some help with the budget.

Posted by Mark Liberman at October 4, 2006 09:15 AM