December 28, 2006

An apology to our readers

This morning, I was suddenly seized by the compulsion to correct an injustice. Geoff Pullum and I were the perpetrators, and our motives were pure. The victim was the BBC News organization, which amply deserved what we did, and worse. But an injustice it was nonetheless: we used an unfair and misleading argument.

The BBC's reporters and editors might be lazy and credulous, scientifically illiterate, bereft of common sense, dishonest, and given to promoting dubious products, but they deserve to be confronted with sound arguments based on solid facts. (A bit of humor is OK as well -- they're an easy target --but that's not the point here.) More important, our readers expect and deserve sound arguments and solid facts from us. But when Geoff and I took the BBC to task for their 12/12/2006 story "UK's Vicky Pollards 'left behind'", we used an invalid argument. It may have cited genuine facts and reasoned to a correct conclusion, but a step in between was, well, fudged.

I felt a little bad about it, but the general outlines of the argument were right, and I didn't have time to do a better job. My conscience has been nagging at me, though, and so this morning I'm going to set the record straight. Or at least, I'll set it as straight as I can. I'm handicapped by the fact that the the particular batch of nonsense that the BBC was serving up on December 12 was based on their misinterpretation of an unpublished, proprietary report, prepared by Tony McEnery for the conglomerate Tesco.

So I can't do the calculations that would allow a fair version of the argument. I'll do what I can for now, and I'll ask Tony if he'll do the corresponding calculations on the data that's unavailable to me. In any case, there's some conceptual value in the discussion, I think, even if we never learn the whole truth about this particular case.

The thing that set it off was the second sentence of the BBC story:

Britain's teenagers risk becoming a nation of "Vicky Pollards" held back by poor verbal skills, research suggests.

And like the Little Britain character the top 20 words used, including yeah, no, but and like, account for around a third of all words, the study says. [emphasis added]

Arnold Zwicky, who still likes to think of the BBC as run by sensible and honest people, commented in passing ("Eggcorn alarm from 2004", 12/14/2006):

[T]his could merely be a report on the frequency of the most frequent words in English, in general. If you look at the Brown Corpus word frequencies and add up the corpus percentages for the top 20 words (listed below), they account for 31% of the words in the corpus. But that would be ridiculous, and it wouldn't distinguish teenagers from the rest of us, so what would be the point?

The point, I figured, was to pander to their readers' stereotype of lexically impoverished teens. To help readers understand this, I made the same general argument that Arnold did, at greater length and with some different numbers ("Britain's scientists risk becoming hypocritical laughing-stocks, research suggests" 12/16/2006):

The Zipf's-law distribution of words, whether in speech or in writing, whether produced by teens or the elderly or anyone in between, means that the commonest few words will account for a substantial fraction of the total number of word-uses. And in modern English, the fraction accounted for by the commonest 20 orthographical word-forms is in the range of 25-40%, with the 33% claimed for the British teens being towards the low side of the observed range.

For example, in the Switchboard corpus -- about 3 million words of conversational English collected from mostly middle-aged Americans in 1990-91 -- the top 20 words account for 38% of all word-uses. In the Brown corpus, about a million words of all sorts of English texts collected in 1960, the top 20 words account for 32.5% of all word-uses. In a collection of around 120 million words from the Wall Street Journal in the years around 1990, the commonest 20 words account for 27.5% of all word-uses.

I should have pointed out that the exact percentage will depend not only on the word-usage patterns of the material examined, but also on

- the details of the text processing (the treatment of digit strings and upper case letters makes a big difference, as does the frequency of typographical errors);

- the size of the corpus -- larger collections will generally yield smaller numbers;

- the topical diversity of the corpus -- new topics bring new words.

(The first factor, by the way, explains why Arnold got 31% and I got 32.5% for the Brown corpus.)

Without controlling carefully for those factors, citing the percent of all words accounted for by the 20 commonest words is almost entirely meaningless. That was the BBC's second mistake. Their first mistake was to imply that a result like 33% is in itself indicative of an impoverished vocabulary.

And in my desire to demonstrate in a punchy way the stupidity of this implication, I did something unfair -- I cited the comparable proportion for the 1190-word biographical sketch on Tony McEnery's web site:

And in Tony McEnery's autobiographical sketch, the commonest 20 words account for 426 of 1190 word tokens, or 35.8% . . .

In fact, Tony used 521 distinct words in composing his 1190-word "Abstract of a bad autobiography"; and it only takes the 16 commonest ones to account for a third of what he wrote. News flash: "COMPUTATIONAL LINGUIST uses just 16 words for a third of everything he says." Does this mean that Tony is in even more dire need of vocabulary improvement than Britain's teens are?

Now, I knew perfectly well that this was an unfair comparison, since the BBC's number was derived by unknown text-processing methods applied to unknown volumes of text on an unknown range of topics. I considered going into all of that -- but decided not to, partly for lack of time, and partly because it weakened the point. So I decided to put forward my own little experimental control instead:

In comparison, the first chapter of Huckleberry Finn amounts to 1435 words, of which 439 are distinct -- so that Tony displayed his vocabulary at a substantially faster rate than Huck did. And Huck's commonest 20 words account for 587 of his first 1435 word-uses, or 40.9%. So Tony beats Huck, by a substantial margin, on both of the measures cited in the BBC story. (And just the 12 commonest words account for a third of Huck's first chapter: and, I, the, a, was, to it, she, me, that, in, and all.) We'll leave it for history to decide whose autobiography is communicatively more effective.

This evened the playing field, since Huck gets a higher 20-word proportion than Tony, for the same text-processing methods applied to a slightly larger text. And I thought it was a good way of underlining the point that Geoff made back on Dec. 8 ("Vocabulary size and penis length"):

Precision, richness, and eloquence don't spring from dictionary page count. They're a function not of how well you've been endowed by lexicographical history but of how well you use what you've got. People don't seem to understand that vocabulary-size counting is to language as penis-length measurement is to sexiness.

Geoff Pullum was then inspired to give the BBC a dose of their own medicine ("Only 20 words for a third of what they say: a replication"), and observed that in the 402-word "Vicky Pollard" story itself, the top 20 words account for 36% of all words used -- more than the 33% attributed to Britain's teens.

This is a great rhetorical move -- the BBC's collective face would be red, if they weren't too busy misleading their readers to pay attention to criticism. But at this point, in fact, Geoff and I may have misled our own readers.

I'll illustrate the problem with another little experiment.

A few days ago, I harvested a couple of million words of news text from the BBC's web site. I then wrote some little programs to pull the actual news text out of the html mark-up and other irrelevant stuff, to divide the text into words (splitting at hyphens and splitting off 's, but otherwise leaving words intact), removing punctuation, digits and other non-alphabetic material, and mapping everything to lower case. As luck would have it, the first sentence, 23 words long, happens to involve exactly 20 different words after processing by this method:

the

father

of

one

of

the

five

prostitutes

found

murdered

in

suffolk

has

appealed

for

the

public

to

help

police

catch

her

killer

This of course means that the 20 commonest word types -- all the words that there are -- account for 100% of the word tokens in the sample so far. If we add the second sentence, 19 additional word tokens for 42 in all, we find that there are now 36 different word types, and the 20 commonest word types occur 26 times, thus covering 26/36 = 72% of the words used. The third sentence adds 24 additional word tokens, for 66 in all; at this point, there 53 different word types, and the 20 commonest ones cover 33/66 = 50% of the words used. After four sentences, the 20 commonest words cover 35/75 = 47% of the words used; after five sentences, 48/105 = 46%.

By now you're getting the picture -- 100%, 72%, 50%, 47%, 46% ... As we look at more and more text, the proportion of the word tokens covered by the 20 commonest word types is falling, though more and more gradually.

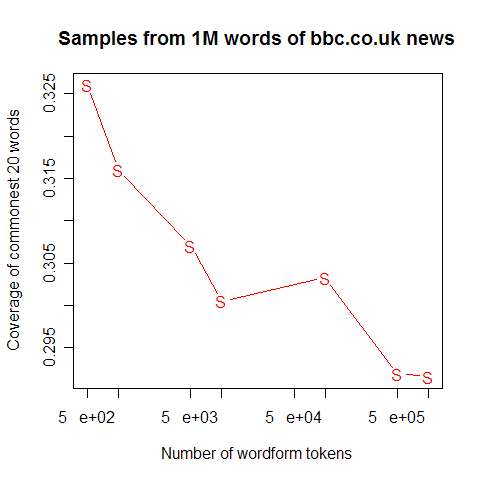

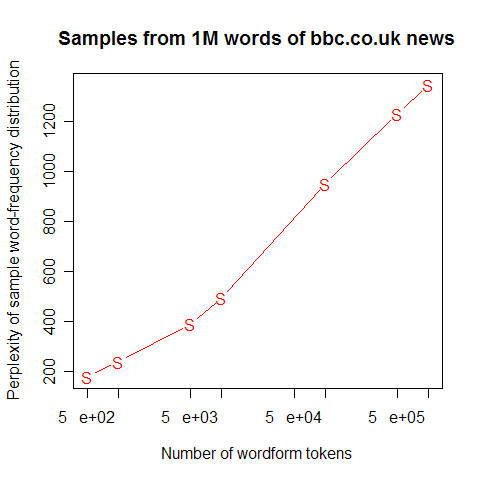

What happens as we increase the size of the sample? Well, the proportion continues to fall in the same sort of pattern. Here's a plot showing the values from 500, 1k, 5k, 10k, 100k, 500k and 1m words in this same sample of BBC text:

So the first 500 words -- roughly one story -- yields a value of about 33%, or about the "one third" that the BBC story cited for Britain's Vicky Pollards. But the million-word BBC sample winds up with a value of about 29%, which is somewhat lower. And if we went to a billion words of text, the number would go a little lower still. So we were in the position of countering a misleading statistic with another misleading statistic.

In fact, the whole notion of using the coverage of the 20 commonest word-types as a measure of effective vocabulary size is not a very good one. The result depends completely on the relative frequency of a few words like "the", "to", "of", "and", "is" and "that". Small differences in style can have a big impact on this value. Dropping or retaining all optional instances of "that", writing in the historical present (which boosts the relative frequency of "is"), systematically choosing phrases like "France's king" instead of "the king of France", etc. -- none of these have any real connection to effective vocabulary size, in any intuitive sense, but they can have a large impact on the relative frequency of the 20 commonest words.

Instead, we'd like a measure that depends on the whole word-frequency distribution.

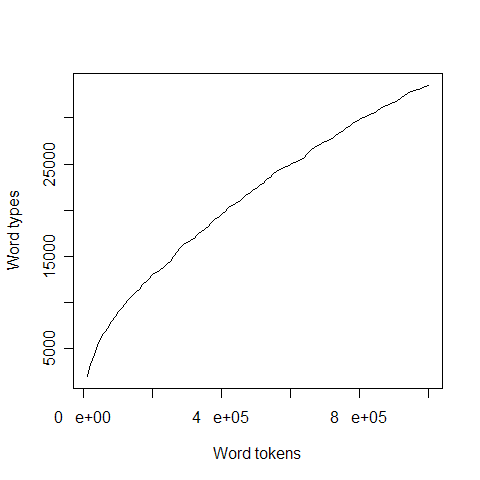

Just measuring the total number of different words is not the right answer -- this number has many of the same difficulties. In particular, it very much depends on the size and topical diversity of the corpus surveyed. As the following plot shows, over the course of a million-word sample of BBC news, the overall vocabulary size, measured in terms of number of distinct word-forms used, continues to increase steadily:

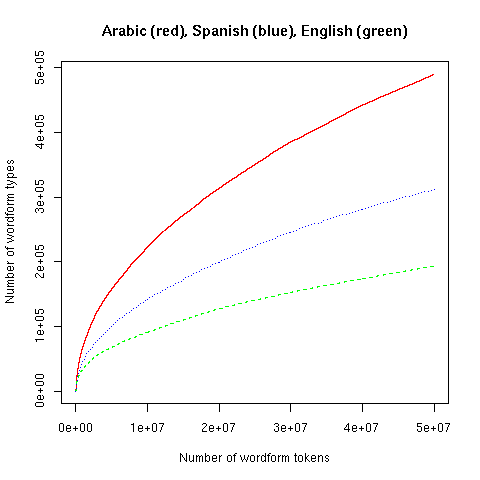

This increase will continue up through much larger corpora than we are likely ever to collect from individual speakers or writer. It makes some sense to quantify active vocabulary in terms of the rate of growth -- this raises some interesting mathematical issues about how to parameterize the function involved, which would be a good (if a bit geeky) topic for another post. Unfortunately, however we quantify it, this will depends on a bunch of very delicate decisions about what a "word" is. Consider the following plot, which follows "vocabulary" growth in the same way through 50 million words of newswire text in English, Spanish and Arabic:

So, it seems, the Arabic vocabulary is about five times richer than the English vocabulary. (Please, people, don't tell the BBC!) No, that's not the right conclusion -- the difference shown in the plot is due to differences in orthographic practices and differences in morphology, not differences in vocabulary deployment. Arabic writing merges prepositions and articles with following words, as if in English we wrote "Thecat sat onthemat" instead of "The cat sat on the mat". And Arabic has many more inflected variants of some word classes, especially verbs. (And Arabic-language newswire also appears to have more typographical errors than English-language newswire, in general.)

This problem makes comparisons across languages difficult, but it also arises for within-language comparisons. You'll get an apparent overall "vocabulary" boost from a wide variety of topical, stylistic and orthographical quirks, such as writing compounds solid; frequent use of derivational affixes like -ish, -oid and -ism; eye dialect; use of proper names; spelling variants and outright bad spelling. As corpus size increases, such factors -- even if they are relatively rare events -- can come to dominate the growth in the type-token curve.

As this suggests, the total count of words that someone (or some group) ever uses is not a very helpful measure of what their ordinary word usage is like. We'd like a measure that reflects the whole distribution of word frequencies, not just the total number of word-types ever spotted, which is almost as arbitrary a measure as the relative frequency of the top 20 words.

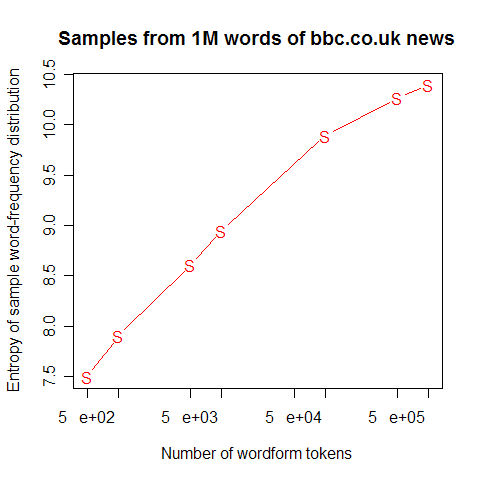

One obvious choice is Shannon's measure of the information content of a probability distribution -- its entropy. This gives us a measure of the information acquired by seeing one additional word from a given source. If we express this as perplexity -- 2 to the power of the entropy -- we get a measure of the vocabulary size that would be associated with a given amount of per-word information, if all vocabulary items were equally likely.

The trouble is, simple measures of entropy (or perplexity) also grow with corpus size. Here's what happens to (unigram) entropy and perplexity over the course of the first million words of BBC news that I harvested the other day:

Now, we could pick some plausible standard corpus size, say 100,000 words, and determine the perplexity of the word-frequency distribution for that corpus (using some well-documented text processing method), and use that as our measure of effective vocabulary. Conclusion: "a 100,000-word sample of BBC newswire has an effective vocabulary, in information-theoretic terms, of 950 words". If we knew what the corresponding number was for Tony McEnery's samples of British teen speech transcripts and weblogs, we'd have some sort of fair comparison.

That's a nice bit of rhetoric, but it's not really what we want. There are at least two sorts of problems. One is that we ought to be measuring information content in terms of how well we can predict the next word in a sequence, not how well we can predict a word in isolation. Another problem is how to find a measure that isn't so strongly dependent on corpus size.

There's a simple (and very clever!) solution, though you have to be careful in applying it. However, it takes a little while to explain, and this post is already too long, so we'll come back to it another day.

BBC News functioned true to type here -- lazy and credulous, scientifically illiterate, bereft of common sense, and the rest of it. You can add class prejudice and age stereotyping in this case as well. And the basic point that Geoff and I made was correct -- the BBC was bullshitting when it implied that British teens are lexically impoverished by noting that in their conversations, "the top 20 words used ... account for around a third of all words". Although the teens probably do need vocabulary improvement, the cited statistic doesn't address that question one way or the other.

But what Geoff and I did was, in effect, to use the journalists' own techniques against them, and our readers deserve better than that.

Posted by Mark Liberman at December 28, 2006 09:42 AM