March 02, 2007

The globalization of educational fads and fallacies

This morning, Fabrice Nauze sent a link to an Op-Ed piece from yesterday's Le Figaro about educational policy in France: Dr. Lucien Israel, "À quand une vraie réhabilitation de l'enseignement primaire?" ("When will there be a real rehabilitation of primary education?"). Fabrice was amused by this article's Gallic version of the Eskimo snow-words myth :

Le registre lexical est pauvre et, par conséquent, la compréhension du monde, de soi-même et des autres bien moindre. Je prendrai l'exemple concret des Esquimaux : leur langue comporte une soixantaine de mots différents pour évoquer la neige : ils perçoivent, par conséquent, une foule de nuances que nous-mêmes ne voyons pas.

The lexicon is poor, and as a result, understanding of the world, of oneself and of others is even less. I will take the specific example of the Eskimo: their language includes about sixty different words for referring to snow: they therefore perceive a host of nuances that we do not see.

But I was more interested in something else. The article revealed to me that there is also a Gallic version of the "whole language" approach to reading instruction, known in France as "la méthode globale". I guess that I should have realized that globalization spreads educational fads just as efficiently as other aspects of culture.

[I need to note that "la méthode globale" is a general pedagogical philosophy, most of which has nothing to do with methods of reading instruction, and that it has a long tradition of independent development in France. The role of international influence in the spread of wholistic, anti-analytic reading-instruction methods during the last decades of the 20th century is not clear to me, though it seems unlikely to be an accident that such methods became widely adopted in the U.S. and in France during the same period. See the bottom of this post for some additional notes and links. ]

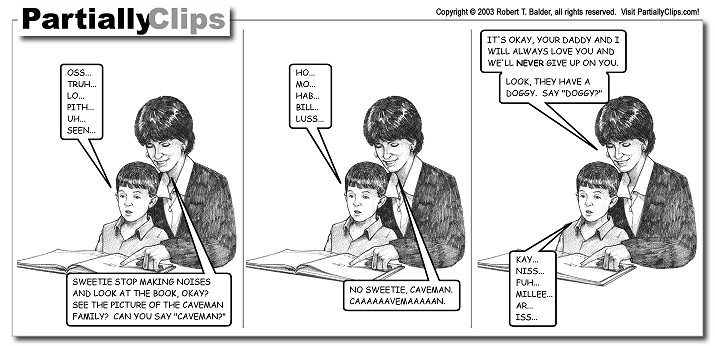

"Whole language" is the idea that children can and should learn to read text in the same easy, natural way that they learn to understand speech -- by being exposed to meaningful communications in everyday situations. On this view, you shouldn't try to teach children to sound out words, or even teach them what the letters of the alphabet are. In cartoon form, it works like this:

Or rather, it doesn't work. As I understand the situation, "Whole language" instruction has been a disaster in practice, ameliorated somewhat by the fact that many teachers don't really apply it, and some children get reading instruction from other sources.

There are few linguistic topics on which scientific opinion -- outside of some unfortunately influential corners of the education-research establishment -- is so unanimous. When David Pesetsky and Mark Seidenberg can join as co-authors of an influential report (republished in Scientific American as K. Rayner, B. Foorman, C. Perfetti, D. Pesetsky and M. Seidenberg, "How Should Reading be Taught?"), you know that something interesting is going on.

For those of you who aren't familiar with the intellectual politics of linguistics, this is roughly like a policy statement on governmental organization co-authored by Friedrich Engels and Otto von Bismarck. David Pesetsky is a staunch supporter of "innate ideas", and Mark Seidenberg is, well, not. Here's what Mark says about the innate-ideas debate in his Overview of Current Research:

... since Chomsky's early work, knowledge of language has been equated with knowing a grammar. Many consequences followed from this initial assumption. For example, if the child's problem is to converge on the grammar of a language, then the problem does seem intractable unless there are innate constraints on the possible forms of grammar. What if we abandon the assumption that knowledge of language is represented as a grammar in favor of, say, neural networks, a more recently developed way of thinking about knowledge representation, learning, and processing? Do the same conclusions about the innateness of linguistic knowledge follow? The answer is: not at all.

The innateness debate is historically relevant here, since as the Wikipedia article on Whole Language explains,

The whole language approach ... grew out of Noam Chomsky's conception of linguistic development. Chomsky believed that humans have a natural language capacity, that we are built to communicate through words. This idea developed a large following in the 1960s. In 1967, Ken Goodman wrote a widely-cited article calling reading a "psycholinguistic guessing game" and chiding educators for attempting to apply unnecessary orthographic order to a process that relied on holistic examination of words.

Though Goodman may have been inspired by Chomsky, most Chomskians have never accepted his views. David Pesetsky's case against the Whole Language approach, as laid out in the handout for a talk he gave in 2000, "The Battle for Language: from Syntax to Phonics", also starts by making the argument that "language is special", with special evolved mechanisms for primary (spoken) language learning. However, the next step in his reasoning is completely different: because no such evolved mechanisms exist for learning written language, children can't rely on any innate "reading acquisition device", and must learn to read by different (and more general-purpose) methods.

Another version of Pesetsky's arguments was presented in 1997 to the ASNE Literacy Committee: "If Language Is Instinctual, How Should We Write and Teach?"

Mark Seidenberg's arguments against the Whole Language approach, as laid out in a 2004 paper (Harm, M. W., & Seidenberg, M. S. Computing the Meanings of Words in Reading: Cooperative Division of Labor Between Visual and Phonological Processes, Psychological Review 111, 662-720), start from the assumption that language is not special at all. On his theory, most knowledge and skills are learned by general methods -- but for reading, this empiricist epistemology converges with Pesetsky's nativist one. And when Seidenberg and Harm trained a neural net model to "read", it learned better and faster when taught using writing-to-sound-to-meaning and writing-to-meaning correspondences than it did when trained by either route alone. Here's a graph from that paper:

I've added colored highlighting, so that the progress of the "Orthography→Semantics" (i.e. writing-to-meaning) system is shown in pink, and the "Orthography→Phonology→Semantics" (i.e. writing-to-sound-to-meaning) system is shown in turquoise, compared to the system with both, which is highlighted in pale green. A popular-press presentation of this research can be found in Emily Carlson, "New study shows phonics is critical for skilled reading", Wisconsin Week, 7/14/04.

My own view is that there is some truth in both the Pesetsky and Seidenberg arguments -- and also in the large volume of other research on the subject, almost entirely antithetical to Whole Language in its conclusions. (See here and here for additional background.)

The most curious -- and perhaps the saddest -- part of this story has been the politicization of the debate. As a blog post at I Speak of Dreams explains ("Whole Language Reading Instruction Is a Continuing Educational Disaster", 12/17/2003):

If you believe in whole language, you are likely to be on the liberal-to-socialist spectrum; if you believe in direct phonics instruction, you have to march in the same parade as Phyllis Schafly, the Eagle Forum, and Dr. Blumenfeld.

An extreme form of this is on display in a 2002 article by Stephen Metcalf ("Reading Between the Lines", The Nation, 1/10/2002):

Why is the same conservative constituency that loves testing even more moonstruck by phonics? For starters, phonics is traditional and rote--the pupil begins by sounding out letters, then works through vocabulary drills, then short passages using the learned vocabulary. Furthermore, to teach phonics you need a textbook and usually a series of items--worksheets, tests, teacher's editions--that constitute an elaborate purchase for a school district and a profitable product line for a publisher. In addition, heavily scripted phonics programs are routinely marketed as compensation for bad teachers. (What's not mentioned is that they often repel, and even drive out, good teachers.) Finally, as Gerald Coles, author of Reading Lessons: The Debate Over Literacy, points out, "Phonics is a way of thinking about illiteracy that doesn't involve thinking about larger social injustices. To cure illiteracy, presumably all children need is a new set of textbooks."

David Pesetsky responded (letter to The Nation 3/7/2002):

The debate was always scientific and educational, not political: To what extent can written language be acquired naturally (the way spoken language is), and to what extent is structured teaching necessary? Representatives of one theory, whole language, asserted in the 1970s and '80s that written language can be acquired naturally. But whole language contradicted what linguistics and cognitive psychology teach us: that written language is a subtle code for spoken language; learning to read is unlike learning to speak; and explicit instruction--phonics--is essential for many. Although whole language should have been a nonstarter, it had a significant impact because of its political marketing. Whole language wrapped itself in liberation rhetoric, promising such things as "the empowerment of learners and teachers." The right wing was jubilant. Here was a left-wing conspiracy that could imperil children's literacy! A flurry of newsletters and websites appeared attacking the left-wing menace of whole language and vigorously promoting phonics.

and poignantly adds:

The war against phonics was a Lysenkoist aberration. It is time to put it to rest. There is no connection between politics and how we should teach children to read, and there never was.

For those of you who aren't familiar with the history of Stalinist science, Trofim Lysenko was a Soviet biologist who claimed to be able to demonstrate the inheritance of acquired characteristics -- which pleased Stalin because it suggested that selfishness and other unsoviet attitudes would disappear from the descendents of people living under socialism. Lysenko's style was congenial to Stalin in other ways -- he came from a peasant family, he supposedly made rapid progress by ignoring the bourgeois formalist skeptics and elevating practice over theory, etc. Stalin put Lysenko in charge of Soviet biology, and thereby destroyed it.

So David is implicitly making a very strong point. Lysenkoism was a politically correct but scientifically mistaken theory of genetics, whose imposition by the Soviet state destroyed Soviet biology for almost 40 years. By analogy, Whole Language is a politically correct but scientifically mistaken theory of reading instruction, whose adoption by the educational establishment has ...

Well, you finish the sentence.

Anyhow, I'm truly sorry to learn that France has been infected by la méthode globale.

And since Dr. Israel is trying to cure this infection, I'm also sorry to tell you that inclusion of the Eskimo snow-words myth is far from the only fault of fact or logic in his article: it offers one misconception after another about language, the brain and reading. This post is already too long, and I've run out of time, so I'll pick the thread up again in a couple of days.

Since I agree with his prescriptions, it's a shame to have to disagree with his arguments. But the misuse of neuroscientific arguments is also becoming an epidemic, perhaps not as fatal as ineffective methods of reading instruction, but still debilitating to the body politic. And it would be a mistake to avoid treating the symptoms because of the politics of the patient.

[Yes, yes, I know, the PartiallyClips cartoon is unfair. But it's funny, and they deserve it.]

[Update -- David Fried writes:

Just a thought. . . is it merely an accident that "whole language" teaching of reading has infected France and not some other country? I'm not referring to the French love of theory, either. It seems inconceivable that whole-language could catch on as a method of teaching reading in any country where the writing system corresponds closely to the phonemic system. I'd be surprised if this particular fad holds any appeal in Spain or Korea. Using phonics to teach reading is certainly tougher when you're contending with the vagaries of English or French spelling, especially considering how the commonest words often have the most peculiar spellings, like "night" and "enough" and "l'oignon" and "fils" and "ville." Does whole language appeal to teachers of Irish Gaelic? It should, if my theory is right . . .

In the case of Irish, there's an additional complicating factor, because most teaching of Irish (even to elementary-school children) is second-language teaching.

And David's general point seems logical, but I'm not sure it's right. For example, the school system in Finland (where the orthography is as rigorously phonemic as it is anywhere) is said to be based on the general pedagogical ideas of Célestin Freinet, who appears to be a patron saint of "la méthode globale". Freinet's ideas were mostly not about reading instruction -- he was more a French John Dewey or a French Maria Montessori than a French Ken Goodman -- but there's clearly some affinity, as suggested by Charles Temple et al., "The 'Global Method' of Celestin Freinet: Whole Language in a European Setting?", Reading Teacher, 48(1) 86-89, 1994. However, according to Marit Korkman et al. "Effects of Age and Duration of Reading Instruction on the Development of Phonological Awareness, Rapid Naming, and Verbal Memory Span", Developmental Neuropsychology, 16(3) 415-431 1999:

Finnish children start school in the autumn of the year they turn 7, and letters or reading-related skills are not taught at all before that. Reading instruction is intense in Grades 1 and 2, and is uniformly based on teaching phonemic analysis and phoneme-grapheme conversions.

It's interesting that the Finns seem to have adopted Freinet's ideas in general, while entirely rejecting (what is said to be) his approach to teaching reading and writing. This emphasizes the need to disentangle general pedagogical (and political) philosophies from the specifics of reading instruction, both in theory and in practice. That is likely to be very difficult to do, I'm afraid. ]

[Bill Poser has more on the history and future of reading instruction here.]

Posted by Mark Liberman at March 2, 2007 04:21 PM