May 20, 2007

Dolphin dialect science?

Inspired by Geoff's post, this morning's Breakfast ExperimentTM at Language Log Labs deals with dolphin dialects. West Philadelphia is a bit short of suitable experimental subjects, so we've had to work with simulated cetaceans. However, there are some significant results, reported below.

Inspired by Geoff's post, this morning's Breakfast ExperimentTM at Language Log Labs deals with dolphin dialects. West Philadelphia is a bit short of suitable experimental subjects, so we've had to work with simulated cetaceans. However, there are some significant results, reported below.

Since we need accurate parameters for the simulation, our crack web search team went looking for the scientific research behind the media hype. Consistent with our well-known glass-half-full outlook, I'm happy to say that we found some. In contrast to the cow dialect story, which was spun up out of nothing by a PR firm promoting regional cheese, there is some real science here.

The Shannon Dolphin and Wildlife Foundation really does exist, and there really is a marine biologist named Simon Berrow, the author of works such as "Discarding Practice and Marine Mammal By-Catch in the Celtic Sea Herring Industry" (Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, 98B (1), 1998) and "EU Habitats Directive and Tourism Development Progammes in the Shannon estuary, Ireland". And there really is an MSc student named Ronan Hickey, who has been funded by the Sea Watch Foundation to do a Comparative study of bottlenose dolphin whistles in the southern Cardigan Bay SAC and in the Shannon Estuary, and who reported some of the results as a poster presentation "Comparison of Whistle Characteristics of Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops Truncates) in Cardigan Bay (Wales) and Shannon Estuary (Ireland) Populations" at the 20th Annual Conference of the European Cetacean Society, April 2-7, 2006, in Gdynia. He won the student paper award -- congratulations, Ronan!

Of course, the fact that there's some actual science behind the media reports doesn't mean that the media reports are informative, responsible or even minimally truthful. The BBC News version is merely exaggerated ( "Bay dolphins have Welsh dialect", but the Times, among others, went completely gaga (Helen Nugent, "Meet the bottlenose boyo of Cardigan Bay – they all speak Welsh at his school", 5/18/2007):

First it was cows who moo with a Somerset drawl. Then it was birds with regional accents. Now scientists say that dolphins living off the coast of Wales have developed a Welsh dialect.

This is a preposterous way to present Ronan Hickey's MSc research, which is less tendentiously described in two abstracts, one from the Cetacean Society conference and one from the web of the Sea Watch Foundation. Both are given in full at the end of this post, with links. On the most optimistic interpretation of this research, the media response has been foolish and exaggerated, as usual. Unfortunately, while there is certainly some serious research going on, a less generous reading leaves it far from clear that there's actually any dolphin dialect discovery to exaggerate.

The abstracts don't give us enough information to evaluate the "dialect" claim, or even to understand exactly what it is, but there are some things in the Sea Watch Foundation abstract that raise significant questions about whether the propensities of Irish and Welsh dolphins to vocalize actually differ at all. First,

Cardigan Bay whistles were collected actively, onboard survey vessels using a deployed hydrophone, while Shannon Estuary whistles were collected passively via a fixed hydrophone.

The difference in collection methodology is obviously a problem. Maybe some of the vocalizations collected from the Cardigan Bay survey vessels meant things like "Damn noisy boats!" or "Hey, let's surf the wake!"; maybe the fixed Shannon Estuary hydrophone was located near a popular dolphin pick-up area ("Any hot babes out there?") or feeding spot ("Wow, herring!").

But an equally serious question has to do with sampling statistics:

Whistles were compared using a series of quantitative parameters and sorted into categories using contour shape. Overall 1882 whistles were analyses [sic] throughout the course of this study. The Vast majority were collected in the Shannon Estuary. A total 32 different whistle categories were described, of which 21 were observed in both populations, 8 were exclusive to the Shannon Estuary and 1 was exclusive to Cardigan Bay

Can we can reject the hypothesis that the cited differences were simply a statistical accident? Not from the information published so far.

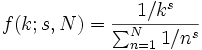

We aren't told what "Vast majority" means, but let's say that 1,600 whistles were collected in Ireland and 282 were collected in Wales. Let's grant that the 32 categories are well defined and were accurately and unambiguously identified, and assume that the relative frequencies of the different categories have the expected "Zipf's Law" type of distribution, where the relative frequency of the kth most common of N categories is given by

Then if we set the exponent s=1.6 (this paper suggests a range of 1.6 to 2.4) and select 1,600 items at (Zipfian) random from a set of 32 categories, we find that our sample is missing one or more of the 32 categories about 20% of the time. If we select 282 times at random from exactly the same distribution, our sample will be missing 8 or more of the 32 categories about 53% of the time. (If someone asks me, I'll post the code that I used to do these simulations, so you can check my work or try the effect of different assumptions.)

Now, Ronan Hickey's actual counts and distributions might be different from my guesses, in ways that would lead to a different conclusion. But from what we've learned so far, there's no reason to be convinced that the underlying repertoires of Welsh and Irish dolphin whistles are actually different at all.

[...] The differences observed in the whistles characteristics between the two populations could be representative of behavioural, environmental, or morphological differences between the Cardigan Bay and Shannon Estuary populations.

Indeed. But the differences could also be representative of sampling error, from what we know so far.

Further Research is required to expand upon the results of this study before the variance in whistle characteristics of Cardigan Bay and the Shannon Estuary populations can be fully understood.

Further research is always good. But a full report of the research done so far would tell us a lot. When a piece of work like this gets into the popular press, the details behind it -- to whatever extent they exist -- should also be made available. In this case, putting Ronan Hickey's MSc thesis on the web would be a good start. (If it's out there and I just couldn't find it, or if there's some other source of published information on this research, please let me know.)

______________________________________________________________________________________________-

As promised, here are the full abstracts:

R.H. Hickey, "Comparison of Whistle Characteristics of Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops Truncates) in Cardigan Bay (Wales) and Shannon Estuary (Ireland) Populations", European Cetacean Society 20th Annual Conference, April 2-7, 2006, Gdynia.

Comparisons of whistle characteristics between geographically isolated populations of delphinid species have reviled variance between locations. The waters of Britain and Ireland are home to three known resident populations of bottlenose dolphins Tursiops truncates: Cardigan Bay (Wales), the Shannon Estuary (Ireland) and the Moray Firth (Scotland). This study compared the whistle repertoires and characteristics of two of these populations; Shannon Estuary and Cardigan Bay. Whistles were compared using a series of quantitative parameters and sorted into categories using contour shape. A total of 32 different whistle categories were described of which 21 were observed in both populations 8 were exclusive to the Shannon Estuary and 1 was exclusive to Cardigan Bay. The average duration of whistles from the Shannon Estuary population was found to be longer than whistles from Cardigan Bay. The average starting, ending, maximum, minimum, and mean frequency of whistles from Cardigan Bay was significantly higher than Shannon Estuary whistles. There was no statistical difference in the whistle rate between the populations. The differences observed in the whistles characteristics between the two populations could be representative of behavioural, environmental, or morphological differences between the Cardigan Bay and Shannon Estuary populations. 66% of the whistles described in this study were common to both populations. This similarity of whistle repertoire between the populations could be the result of a recent divergence time between the populations or possible transition of individuals between the locations. To further understand the whistle characteristics of bottlenose dolphins in Britain and Ireland, it would be necessary to include whistles from the Moray Firth population in Scotland.

Seawatch Foundation web site: Ronan Hickey, University of Wales, Bangor: Comparative study of bottlenose dolphin whistles in the southern Cardigan Bay SAC and in the Shannon Estuary.

In previous studies, comparisons of whistle characteristics between geographically isolated populations of delphinid species have revealed variation between locations. The waters of Britain and Ireland are home to three known resident populations of bottlenose dolphins Tursiops truncatus : Cardigan Bay (Wales), the Shannon Estuary (Ireland) and the Moray Firth (Scotland). This study compared the rate, repertoires and characteristics of whistles of two of these populations: Shannon Estuary and Cardigan Bay. Comparisons between years, groups and different group sizes were also carried out within the Shannon Estuary population. Cardigan Bay whistles were collected actively, onboard survey vessels using a deployed hydrophone, while Shannon Estuary whistles were collected passively via a fixed hydrophone. Whistles were compared using a series of quantitative parameters and sorted into categories using contour shape. Overall 1882 whistles were analyses throughout the course of this study. The Vast majority were collected in the Shannon Estuary. A total 32 different whistle categories were described, of which 21 were observed in both populations, 8 were exclusive to the Shannon Estuary and 1 was exclusive to Cardigan Bay. The average duration of whistles from the Shannon Estuary population was found to be longer than whistles from Cardigan Bay. The average starting, ending, maximum, minimum, and mean frequency of whistles from Cardigan Bay was significantly higher than Shannon Estuary whistles. There was no statistical difference in the whistle rate between the populations. Variations in whistle parameters and frequency of occurrence of whistle categories were also observed in comparisons within the Shannon Estuary population. Whistle rates increased with increasing group size. On a side note, dolphins in the Shannon Estuary were observed to have cyclic behaviour, which was influenced by tidal times. Dolphins were most commonly encountered during the mid ebb tide. The differences observed in the whistles characteristics between the two populations could be representative of behavioural, environmental, or morphological differences between the Cardigan Bay and Shannon Estuary populations. Further Research is required to expand upon the results of this study before the variance in whistle characteristics of Cardigan Bay and the Shannon Estuary populations can be fully understood.

The SDWF has a web site with a page that describes the "dialect" research, which lists two papers:

Hickey, R. (2005) Comparison of whistle repertoire and characteristics between Cardigan Bay and the Shannon estuary populations of Bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) with implications for passive and active survey techniques. School of Biological Sciences, University of Wales, Bangor

Berrow, S.D., O’Brien, J. & Holmes, B. (2006) Whistle production by bottlenose dolphins Tursiops truncatus in the Shannon estuary. Irish Naturalists' Journal 28(5), 208-213.

The first of these is apparently Hickey's MSc report, which hasn't been published and isn't available on the web, as far as I can tell. The second one is an archival publication, but is not available in digital form -- and also doesn't include the "dialect" comparison.

Some other research suggesting that the idea of "dolphin dialects" is not an unreasonable one:

Rendell, L. and H. Whitehead (2001). Culture in whales and dolphins. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 24(2): 309-24; Discussion 324-82.

Abstract: Studies of animal culture have not normally included a consideration of cetaceans. However, with several long-term field studies now maturing, this situation should change. Animal culture is generally studied by either investigating transmission mechanisms experimentally, or observing patterns of behavioural variation in wild populations that cannot be explained by either genetic or environmental factors. Taking this second, ethnographic, approach, there is good evidence for cultural transmission in several cetacean species. However, only the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops) has been shown experimentally to possess sophisticated social learning abilities, including vocal and motor imitation; other species have not been studied. There is observational evidence for imitation and teaching in killer whales. For cetaceans and other large, wide-ranging animals, excessive reliance on experimental data for evidence of culture is not productive; we favour the ethnographic approach. The complex and stable vocal and behavioural cultures of sympatric groups of killer whales (Orcinus orca) appear to have no parallel outside humans, and represent an independent evolution of cultural faculties. The wide movements of cetaceans, the greater variability of the marine environment over large temporal scales relative to that on land, and the stable matrilineal social groups of some species are potentially important factors in the evolution of cetacean culture. There have been suggestions of gene-culture coevolution in cetaceans, and culture may be implicated in some unusual behavioural and life-history traits of whales and dolphins. We hope to stimulate discussion and research on culture in these animals.

Rendell, L.E. and H. Whitehead (2003). Vocal clans in sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus). Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological Sciences 270(1512): 225-31. ISSN: 0962-8452.

Posted by Mark Liberman at May 20, 2007 09:55 AMAbstract: Cultural transmission may be a significant source of variation in the behaviour of whales and dolphins, especially as regards their vocal signals. We studied variation in the vocal output of 'codas' by sperm whale social groups. Codas are patterns of clicks used by female sperm whales in social circumstances. The coda repertoires of all known social units (n = 18, each consisting of about 11 females and immatures with long-term relationships) and 61 out of 64 groups (about two social units moving together for periods of days) that were recorded in the South Pacific and Caribbean between 1985 and 2000 can be reliably allocated into six acoustic 'clans', five in the Pacific and one in the Caribbean. Clans have ranges that span thousands of kilometres, are sympatric, contain many thousands of whales and most probably result from cultural transmission of vocal patterns. Units seem to form groups preferentially with other units of their own clan. We suggest that this is a rare example of sympatric cultural variation on an oceanic scale. Culture may thus be a more important determinant of sperm whale population structure than genes or geography, a finding that has major implications for our understanding of the species' behavioural and population biology.