May 27, 2007

In the weeks and months

At President Bush's May 24 press conference, his opening statement included the following passage:

This summer is going to be a critical time for the new strategy. The last of five reinforcement brigades we are sending to Iraq is scheduled to arrive in Baghdad by mid-June. As these reinforcements carry out their missions the enemies of a free Iraq, including al Qaeda and illegal militias, will continue to bomb and murder in an attempt to stop us. We're going to expect heavy fighting in the weeks and months. We can expect more American and Iraqi casualties. We must provide our troops with the funds and resources they need to prevail.

His prediction has been featured in broadcast news sound bites over the past couple of days, and every time I hear it, I notice the apparent failure to complete the thought. "In the weeks and months ahead"? "In the weeks and months to come"? Presumably something like that was in the original text.

The disfluency before "weeks" (a broken-off production of "month"?) makes it clear that something went wrong in the president's performance:

Another phonetic signpost of trouble was the size of the silent pause preceding that sentence: 2.25 seconds, vs. about 1.5 to 1.7 seconds for W's within-paragraph pauses up to that point.

In reporting on the news conference, some stories supplied a suitable time modifier in parentheses or outside the quotation marks:

“We’re going to expect heavy fighting in the weeks and months” to come, Bush told a White House news conference.

"This summer is going to be a critical time for the new strategy," said Bush. "We're going to expect heavy fighting in the (coming) weeks and months."

Others relied on a semantically complete paraphrase, or gave up and just used the quote intact, relying on their readers to understand the meaning in context.

In fact, not much context is required. I suspect that if you ask practiced readers of journalistic, political and commercial discourse in English to complete the phrase

in the weeks and months __

most of them would supply "ahead" or "to come" as their first guess.

That's certainly what an algorithm based on contextual frequency would do. Google finds 310,000 pages containing {"in the weeks and months"}, and almost two thirds of them continue either as "in the weeks and months ahead" (140K) or "in the weeks and months to come" (65K). If we add "in the weeks and months following" (27.3K), "in the weeks and months after" (27.2K), and "in the weeks and months that followed" (14.1), we get 273.6K, or 88%. (Yes, I know that assuming superposition of Google counts is naive, but the additivity of counts is probably good enough, these days, to support this particular argument.)

To use one of the president's signature words, I find it interesting that "in the weeks and months __" is so radically biased towards the future. In comparison, Google has only 2 hits for "in the weeks and months earlier", 7 for "in the weeks and months previous", 8 for "in the weeks and months that preceded". The only even reasonably common past-oriented continuation that I can come up with is "in the weeks and months before", with a mere 966.

But I wonder what larger patterns this is part of. Is it just a fact about particular English conjunction "weeks and months", or perhaps the prepositional phrase "in the weeks and months"? Or could there be a more general bias towards following events into the future rather than tracking them back into the past? It's obviously time for a Breakfast Experiment™.

The president's example can be generalized in many directions. Given the available tool of textual search on the web, the easiest dimensions to check are the ones defined by simple string substitutions. So I'll pour another cup of coffee and give it a try.

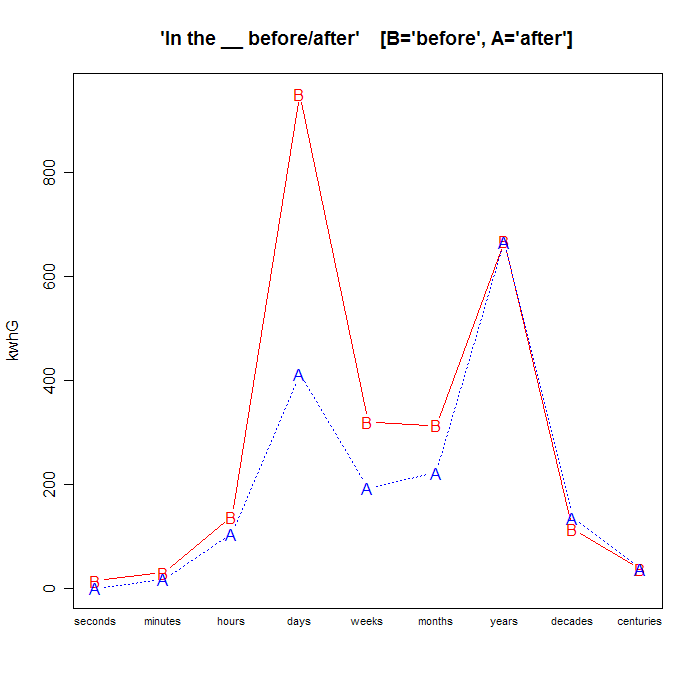

If we look at a range of time-units from seconds to centuries, and limit ourselves to the common past- vs. future-oriented continuations "before" and "after", we get this:

seconds |

minutes |

hours |

days |

weeks |

months |

years |

decades |

centuries |

|

| "in the __ before" | 15.4K |

30.6K |

138K |

952K |

320K |

314K |

668K |

115K |

37.6K |

| "in the __ after" | 799 |

18.1K |

106K |

413K |

193K |

223K |

667K |

137K |

38.5K |

| before/after ratio | 19.3 |

1.7 |

1.3 |

2.3 |

1.7 |

1.4 |

1.0 |

0.84 |

0.98 |

| before percentage | 95% |

63% |

57% |

70% |

62% |

58% |

50% |

46% |

49% |

The ratio of total before counts to total after counts is 1.44 (2.59M to 1.8M), and the overall percentage of before in the before+after total is 59%.

So it's clear that there's no general bias in favor of looking towards the future -- in this particular set of string-substitution contexts, the past is winning.

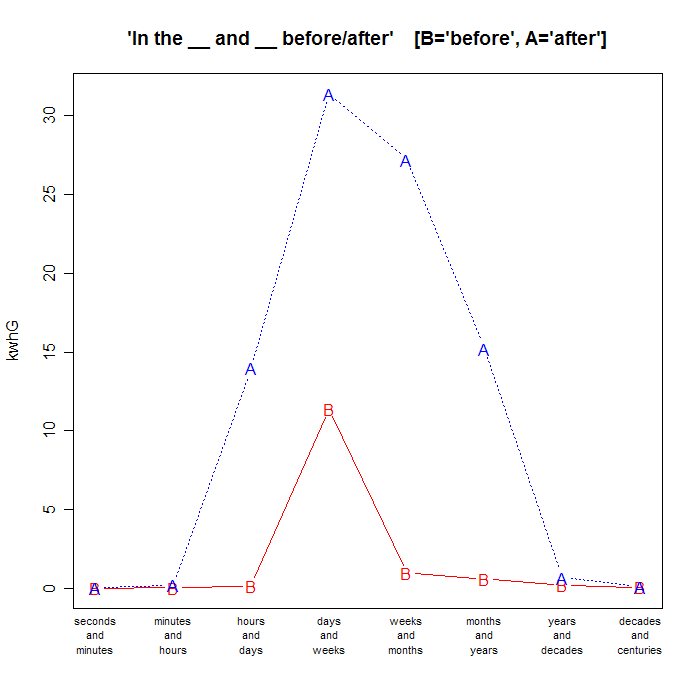

But if we do the same thing with conjunctions of adjacent pairs of time units in order of increasing size, like "in the seconds and minutes before" or "in the hour and days after", we get this very different pattern:

| seconds and minutes |

minutes and hours |

hours and days |

days and weeks |

weeks and months |

months and years |

years and decades |

decades and centuries |

|

| "in the __ before" | 1 |

51 |

155 |

11.4K |

966 |

597 |

198 |

69 |

| "in the __ after" | 8 |

208 |

14K |

31.4K |

27.2K |

15.2K |

688 |

85 |

| before/after ratio | 0.13 |

0.25 |

0.01 |

0.36 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

0.29 |

0.81 |

| before percentage | 11% |

20% |

1% |

27% |

3% |

4% |

22% |

45% |

Now the ratio of total before counts to total after counts is 0.15 (13.4K to 88.8K), and the overall percentage of before in the before+after total is 13%. When we look at the all the conjunctions of time units in ascending order of size -- not just "weeks and months" -- the future is winning by a landslide!

Here's the same data, presented graphically. When the phrasal head is a single time unit, the past generally wins:

But when the phrasal head is a conjunction of time units in ascending order, the future kicks the past's ass:

What's going on here?

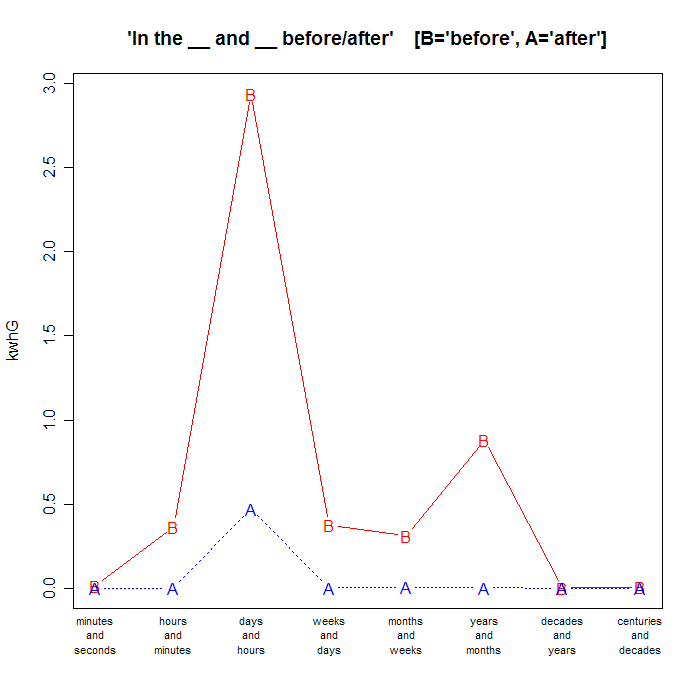

The consistency of the pattern across time-units makes it clear that it's not a fact about any particular lexical item, or about any particular collocation of lexical items. Is the effect due only to the conjunction of (adjacent?) time units, or does it matter that tme units are ordered from smaller to larger? Let's try it the other way around:

| minutes and seconds |

hours and minutes |

days and hours |

weeks and days |

months and weeks |

years and months |

decades and years |

centuries and decades |

|

| "in the __ before" | 15 |

367 |

2.94K |

376 |

314 |

882 |

2 |

6 |

| "in the __ after" | 1 |

1 |

474 |

3 |

6 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

| before/after ratio | 15 |

367 |

6.2 |

125 |

53 |

221 |

- |

- |

| before percentage | 93.8% |

99.7% |

86% |

99% |

98% |

99.5% |

100% |

100% |

Changing the order of the time units, so that the larger one comes first, flips the effect towards the past. Now the ratio of total before counts to total after counts is 10 to 1 (4,902 to 489), and the overall percentage of before in the before+after total is 91%. Graphically:

OK, I think it's clear what's going on.

It's natural to think of the time-scale narrowing down -- zeroing in -- as our perspective gets closer in time to the event under discussion. And it's natural to think of (say) "hours and days" as hours followed (temporally) by days, while "days and hours" is days followed temporally by hours.

From those two assumptions, it follows that a conjunction of time units in order of increasing size (like "hours and days") will more naturally be used to describe time after an event; while a conjunction of units in decreasing-size order (like "days and hours") will more naturally be used for time before an event.

And that's what happens!

If this theory is right, then the same thing ought to happen in French or Chinese or Turkish -- as long as the assumptions continue to hold, about zeroing in on events and listing time periods in chronological order.

[Update -- Anatol Stefanowitsch writes:

cool.

It also works in German (see attached .csv file).

Turned into html tables, the file that Anatol attached looks like this:

Table 1 -- smaller units first:

| sekunden und minuten |

minuten und stunden |

stunden und tagen |

tagen und wochen |

wochen und monaten |

monaten und jahren |

jahren und jahrzehnten |

jahrzehnten und jahrhunderten |

|

| in den _ (vor|bevor|davor|vorher) | 1 |

1 |

10 |

871 |

992 |

87 |

181 |

18 |

| in den _ (nach|nachdem|danach|nachher) | 0 |

7 |

203 |

1350 |

1270 |

411 |

310 |

18 |

| vor/nach ratio | - |

0.14 |

0.05 |

0.65 |

0.78 |

0.21 |

0.58 |

1 |

| vor percentage | 100% |

13% |

5% |

39% |

44% |

17% |

37% |

50% |

Table 2 -- larger units first:

| minuten und sekunden |

stunden und minuten |

tagen und stunden |

wochen und tagen |

monaten und wochen |

jahern und monaten |

jahrzehnten und jahren |

jahrhunderten und jahrzehnten |

|

| in den _ (vor|bevor|davor|vorher) | 0 |

9 |

116 |

382 |

66 |

33 |

0 |

3 |

| in den _ (nach|nachdem|danach|nachher) | 0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| vor/nach ratio | - |

- |

116 |

- |

33 |

- |

- |

- |

| vor percentage | - |

100% |

99% |

100% |

97% |

100% |

- |

100% |

I venture to suggest that the kind of research represented by this collective Breakfast Experiment™ deserves a name. "Yes", I hear you say, "how about 'Computational Linguists With Way Too Much Time On Their Hands'?" No, actually, what I had in mind was something more like "Google Cognitive Linguistics".]

Posted by Mark Liberman at May 27, 2007 07:03 AM