September 06, 2007

The "fiction gap": empathy, prestige, or what?

According to Eric Weiner, "Why Women Read More than Men", NPR.org, 9/5/2007,

A couple of years ago, British author Ian McEwan conducted an admittedly unscientific experiment. He and his son waded into the lunch-time crowds at a London park and began handing out free books. Within a few minutes, they had given away 30 novels.

Nearly all of the takers were women, who were "eager and grateful" for the freebies while the men "frowned in suspicion, or distaste." The inevitable conclusion, wrote McEwan in The Guardian newspaper: "When women stop reading, the novel will be dead."

You can read that whole story here: Ian McEwan, "Hello, would you like a free book?", The Guardian, 9/20/2005. According to McEwan's report, he gave away the 30 novels to the "lunchtime office crowds picnicking on the grass" near his house in London, and only one man "was tempted", so that 97% of the books went to women. Eric Weiner gives a more general market statistic that is almost as striking:

When it comes to fiction, the gender gap is at its widest. Men account for only 20 percent of the fiction market, according to surveys conducted in the U.S., Canada and Britain.

I haven't been able to track down any of those surveys -- if you know a reference, please tell me. I did find Reading at Risk: a Survey of Literary Reading in America, NEA Research Division Report #46, June 2004, which says that in 2002, 55.1% of American women over the age of 18 read "literary" works, as opposed to 37.6% of men. (If they read equal amounts, that would give women 59% of the market; but presumably the women read more.)

We'll come back to some other facts from this report later on; for now, let's go forward with Weiner:

Theories attempting to explain the "fiction gap" abound. Cognitive psychologists have found that women are more empathetic than men, and possess a greater emotional range -- traits that make fiction more appealing to them.

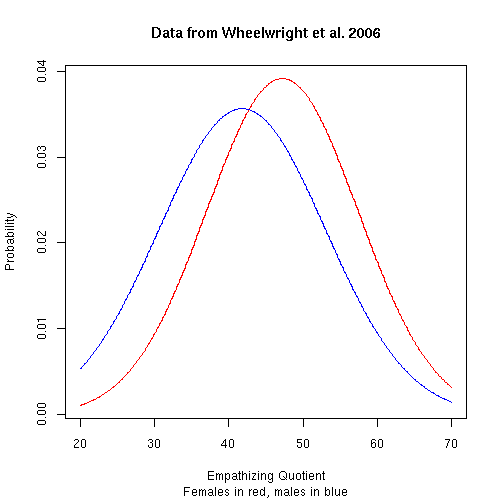

This is all true, but it's not clear that it's enough to explain what's going on. Simon Baron-Cohen and others have devised what they call an "Empathizing Quotient", and tested many men and women for it. On the basis of the data presented in a paper of their that I discussed at length last year ("Stereotypes and facts", 9/24/2006), the distribution of EQs for men and women in the general population should look something like this (mean 41.8, sd 11.2 for men; mean 47.2, sd 10.2 for women):

I guess you could make something up about non-linear amplification of the effect, but it's not obvious that this difference should translate into 80% of the fiction market for women.

But let's go on, because we're about to meet an old friend:

Some experts see the genesis of the "fiction gap" in early childhood. At a young age, girls can sit still for much longer periods of time than boys, says Louann Brizendine, author of The Female Brain.

"Girls have an easier time with reading or written work, and it's not a stretch to extrapolate [that] to adult life," Brizendine says. Indeed, adult women talk more in social settings and use more words than men, she says.

Dr. Brizendine, apparently not any more impressed by recent contrary evidence that by earlier contrary meta-analyses, continues to show that she was a worthy winner of the Goropius Becanus award for 2006. For lagniappe, she turned Wiener on to mirror neurons:

Another theory focuses on "mirror neurons." Located behind the eyebrows, these neurons are activated both when we initiate actions and when we watch those same actions in others. Mirror neurons explain why we recoil when seeing others in pain, or salivate when we see other people eating a gourmet meal. Neuroscientists believe that mirror neurons hold the biological key to empathy.

(Mirror neurons are actually located both in the inferior frontal gyrus and in the inferior parietal lobule -- which is "behind the eyebrows" only in the sense that the whole brain is -- and according to some theories of their function, this pairing of posterior and anterior brain regions is essential to their function in abstracting over perception and action. But anyhow...)

The research is still in its early stages, but some studies have found that women have more sensitive mirror neurons than men. That might explain why women are drawn to works of fiction, which by definition require the reader to empathize with characters.

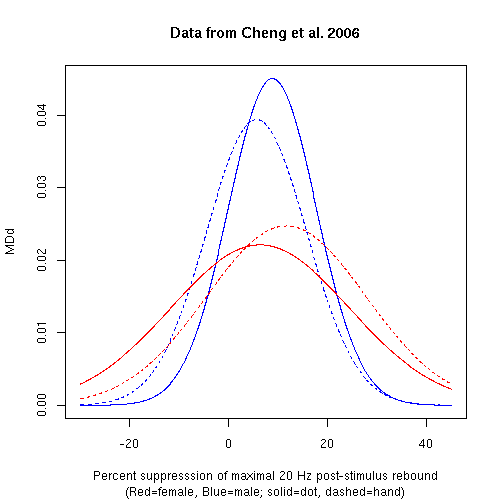

I've only found one study, Ya-Wei Cheng, et al., "Gender differences in the human mirror system: a magnetoencephalography study", NeuroReport, July 31, 2006, 17:11. They studied 10 males and 10 females (all Taiwanese) between 20 and 32 years old.

Neuromagenetic mu (∼20 Hz) oscillations were recorded over the right primary motor cortex, which reflect the mirror neuron activity, in 10 female and 10 male participants while they observed the videotaped hand actions and moving dot. In accordance with previous studies, all participants had mu suppression during the observation of hand action, indicating activation of primary motor cortex.

As you'd expect for a paper published in NeuroReport (which is a sort of quick sketch-pad for neuroscience results that are interesting but not yet ready for prime time), the gender-related effects are not very strong:

When the normalized suppression of the maximal 20 Hz post-stimulus rebound was quantified, women had the mean ± SEM as 11.6±5.1% in the hand and as 6.3 ± 5.7% in the dot. For men, the mean ± SEM was 5.6 ± 3.2% and 8.8 ± 2.8%, respectively. The statistical results did not show a major effect in the gender itself (F1,18 = 0.767, P = 0.393), but in the condition itself (F1,18 = 4.521, P = 0.048) and their interaction (F1,18 = 9.331, P = 0.007).

Converting SEM ("standard error of the mean") to standard deviations, and plotting gaussians with the cited values, we get something like this:

The men had a bit less mu suppression for the hand compared to the dot, while the women had a bit more, and the interaction was statistically significant -- but it's not an enormous effect. (The biggest and most obvious trend, actually, seems to be that the women were more variable. Oh, and please note that this is not really a picture of their data distribution -- it's a display of gaussian distributions based on the means and standard errors that they cite. Their actual data is probably quite a bit messier.)

Cheng et al. note some problems with their study -- including the fact that the moving hand was a male one -- to be addressed in further work:

The significant interaction between the conditions and the genders may in part result from the different strategy of the participants (women versus men) during the observation of moving dot. Men might treat this stimulus as an 'object' to trigger the canonical neurons of the premotor cortex, but women did not. One MEG study by Hari et al. [5] reported that the viewing of a moving dot did suppress the ∼20 Hz poststimulus rebounds, but the suppression was weaker than that observed during action viewing. Here it was found that such suppression was modulated by the participant's gender. Moreover, the present findings might reflect partially the opposite-gender response, that is, female participants responded stronger to the displayed male hand, although the equivalent conjectural rate between the genders was controlled to ensure the male hand rendered androgynous. To address this issue, we need a further study with the displayed female hand.

These results are less striking, I think, than the much more direct measures of empathy reported by Baron-Cohen's group -- this seems to be another example where the neuroscience, though interesting and suggestive from a scientific point of view, actually adds nothing but empty intellectual prestige-symbols to the larger argument (which here is about the role of empathy in explaining the "fiction gap").

Overall, I'm not impressed by the strength of the argument from empathy (and the mirror-neuron stuff doesn't increase the strength of the argument at all, it just adds logically-irrelevant pizzazz). What else might be going on?

Well, let's take a look at some of the other data from the 2004 NEA study. The differences among racial and ethnic groups were as large as, or larger than, the differences between males and females:

Do we think that "White Americans" are more empathetic than "African Americans", who in turn are more empathic than "Hispanic Americans"? I certainly don't -- those differences must have some other explanation. (And it's not hard to come up with several hypotheses.)

What about the huge effects of education? Again, do we think that people with more education are more empathetic? And what about the effects of income, which are smaller than the effects of education, but (at the extremes) are as large as the effects of sex?

I'd like to suggest looking in a different direction to explain at least some of these effects. Most sociolingustic variables pattern in exactly the same way with respect to education, socio-economic status, and sex. (You can read all about one example, with graphs and tables, in a Language Log post from a few years ago: "The internet pilgrim's guide to g-dropping", 5/10/2004).

The fact is, reading "literary works" is a cultural trait associated with prestige groups in our society. In most cases, traits associated with education, prestige and formality are also found more strongly in women rather than men, other things equal.

It's uncertain, not to say controversial, why this is; and the effect (though sometimes large) is probably not strong enough to explain an 80% market share (but maybe that figure is exaggerated, I don't know). All the same, I bet that (whatever accounts for) the sex-prestige interaction has as much to do with the fiction gap as those mirror neurons do.

[In both cases, the amount of explanation might well be "not much" -- but this is an interesting example of amplifying effect of ideology. Someone who was disposed to do so -- as I certainly am not -- could make up a story about how this shows us, once again, that women are insecure social climbers obsessed with displays of status markers. That story would be at least as well supported by the "scientific" evidence as the story about how women are motivated to read fiction because, as Brizendine told Wiener, ""Reading requires ... the ability to 'feel into' the characters. That is something women are both more interested in and also better at than men." ]

[Helen DeWitt writes:

(Hand to brow)

I have a friend, Lawrence Powers, who once demonstrated the circumstances in which men, given the chance, will talk your ear off -- we met at an art exhibition in Kreuzberg, he happened to mention that he was obsessed with soundtracks of video games (Americans play Japanese games, hence prog rock soundtracks, playing on non-hackable consoles, Europeans play European games, disco soundtracks, on hackable computers, hence demo parties, hence open-source movement, to condense ruthlessly), WOW, I said, and the rest was history, or rather a 5 hour discourse punctuated by the occasional WOW... Anyway, the discourse was definitely WOW-worthy, because Lawrence was talking also about generations of game-players, in the game world, he explained, a generation is about 6 years, he has 2 brothers, an older and a younger, but they belong to different generations, they played different games...

While he was talking I was thinking -- yeah, but I'll bet this is only really true of boys, there are girls who play games, sure, but I don't think they fall into generations according to the games they play, I don't think computer games define the sensibility of a cohort of girls...

The medium through which people prefer to engage with fiction may well be indicative of /something/. But if one group of people likes novels, and another group likes computer games, and a third likes films, taking one particular form of fiction without looking at the others tells us nothing about liking for fiction, let alone empathy. (It's not clear why an engagement with fiction in textual form should show a greater degree of empathy than an engagement with fiction in other forms.)

As far as McEwan's experiment goes, anyway, the observer may have affected the observations. I used to live in East London, spent a lot of time reading in pubs; I used to get into conversations with men who'd left school at 16 to go into the Army. As it turned out, they'd read a fairly wide range of fiction -- Nabokov, Welsh, Barnes and Mailer were some names that were mentioned. If a blonde American were to walk up to strange men in a British park and offer them a choice of novels she might get more takers than a 50-something-year-old British man. McEwan's slapdash approach to experiment design, of course, confirms all our worst fears about the scientific woollymindedness of both men and women in the arts.

Well, I wish I could say that that men and women in the sciences were uniformly clear-headed on such topics. McEwan's failure to control for the sex of the book-distributors is exactly mirrored by the failure of the mirror-neuron experimenter to control for the sex of the imaged hand -- though they did worry about it, perhaps because a reviewer brought it up. And in the more general domain of over-interpretation, (some of) the scientists are likely cross the finish line well in front.

The 2004 NEA report finds a large relative decline in male "literary" reading during the past 10 years, roughly as computers and digital gaming and the internet have spread. I like the idea of computer/video games as empathy projected through contemporary male culture. Even if the empathy sometimes comes disguised as giblets...]

[Russell Borogove writes:

Regarding the experiment of handing out free novels, besides controlling for the sex of the book distributors, I'd be very interested to know what books, exactly, were being given out (Tom Clancy, Stephen King, Christopher Moore, Barbara Kingsolver?), and what happens if you try and give away something non-book but relatively gender-neutral -- calendars of landscape photography, for instance.

Me too. But mostly, I'd like to track down that 80%-market-share feature. You could almost get it from another widely-quoted statistic -- that romance novels amount to 53% of fiction sales (I quote the figure from memory, but I think it's as I've read it.) If essentially all the romances were bought by women, and the rest of the fiction were divided half-and-half, you'd have about 77% market share, which would round up to 80%.

][Ann Bartow at Feminist Law Professors has a discussion of Weiner and related articles. ]

Posted by Mark Liberman at September 6, 2007 08:53 AM