November 17, 2007

Heynabonics

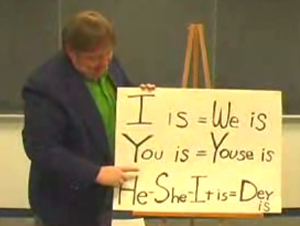

One of the latest YouTube sensations is, surprisingly enough, a metalinguistic exploration of the speech patterns of northeastern Pennsylvania. It's called "Heynabonics," and it's the handiwork of the comedy troupe One Laugh at Least. The sketch takes place in a classroom, with a hyper-demotic teacher instructing clueless outsiders in "the unofficial dialect of nort'eastern Pennsylvania." Though the short film now posted to YouTube was created in 2005, the troupe has actually been performing the sketch since 1998, when the Oakland Ebonics controversy was still fresh in the national consciousness. (More background here and here.)

One of the latest YouTube sensations is, surprisingly enough, a metalinguistic exploration of the speech patterns of northeastern Pennsylvania. It's called "Heynabonics," and it's the handiwork of the comedy troupe One Laugh at Least. The sketch takes place in a classroom, with a hyper-demotic teacher instructing clueless outsiders in "the unofficial dialect of nort'eastern Pennsylvania." Though the short film now posted to YouTube was created in 2005, the troupe has actually been performing the sketch since 1998, when the Oakland Ebonics controversy was still fresh in the national consciousness. (More background here and here.)

The word Ebonics has generated various other jocular folk-dialectal labels via blending, notably redneck-bonics and y'allbonics — though both of those examples are used to mock routinely stigmatized Southern dialect features. The "Heynabonics" sketch, on the other hand, pokes fun at a dialect region that most Americans don't consider salient enough to stigmatize. For instance, if you watch the US version of "The Office," which takes place in Scranton, Pa., you won't hear much of anything identifiable as local dialect (besides a suitably glottalized pronunciation of "Scra'on"). So the YouTube video is for many viewers probably their first exposure to the regional speech of northeastern Pennsylvania, or at least a caricature thereof.

For students of perceptual dialectology the video is reminiscent of many other folk-dialectal representations from around the U.S. Even staying within the state of Pennsylvania one can find many self-mocking catalogues of features from the Pittsburgh dialect region. Barbara Johnstone, as part of her Pittsburgh Speech & Society project, has analyzed local works of folk lexicography that instruct readers "how to speak like a Pittsburgher." And just as y'all is taken as emblematic of Southern speech, the second-person plural pronoun yinz or yunz is seen as embodying Pittsburghese, to the extent that Pittsburghers sometimes call themselves yinzers and refer to their home town Yinzburgh. In the "Heynabonics" video, the regionally emblematic feature is not a pronoun (even though the instructor drills the students on non-standard youse) but rather a tag question: heyna.

The Dictionary of American Regional English treats this tag question under the heading haina and supplies the following 1986 citation from its files, given by a respondent from northeastern Pennsylvania:

The Dictionary of American Regional English treats this tag question under the heading haina and supplies the following 1986 citation from its files, given by a respondent from northeastern Pennsylvania:

Putting haina on the end of a statement makes the statement a question. It doesn't matter who you're talking to, or when the thing happened. "You're going dancing Friday night, haina?" means "Are you going dancing Friday night?" "He did that last night, haina?" means "Did he do that last night?"

Coalspeak, an online glossary of Pennsylvania's anthracite coal region, provides this definition:

hayna or heyna or henna or haynit: request for affirmation, like "ain't it so?" or "isn't that right?". See hain't. This is primarily a Luzerne County word, very common in Hazleton, Wilkes-Barre, and surrounding areas. On a related note, many Pennsylvania Dutch sentences end with the phrase "say not". That sure smells like sulfur, henna?" "It sure is cold tonight, heyna or no?"

And under hain't it has:

hain't: another variation on ain't. "Hain't it?" is likely where heyna comes from.

DARE supports this derivation, since it cross-references haina with ainna, identified as a contraction of ain't it, influenced by German nicht wahr. (The citations for ainna come from areas with historically large German settlements, such as Milwaukee.) Coalspeak's linkage of heyna/haina to Pennsylvania Dutch say not may have some validity — in a discussion on the American Dialect Society mailing list last year, Arnold Zwicky mentioned another Pennsylvania Dutch variant, ai not. Elsewhere, Arnold explained that "the Pa. Dutch English tag is just a straight-out borrowing from Pa. Dutch (which is surely a calque on a German dialect tag)." Paul Johnston, meanwhile, suggested a possible connection to the Scottish tag ai no, since Ulster-Scots were also early settlers in the region, though that seems less likely.

Interestingly enough, Hindi has a similar tag question formation, hai na, roughly translatable as 'is not?'. The ADS discussion last year was sparked by a mention of the Hindi tag in a BBC News report on a dictionary of "Hinglish" as used by South Asian immigrants in Britain. The dictionary, The Queen's Hinglish, evidently derives the popular British tag question innit from Hindi hai na. An article in The Telegraph elaborates, "The ubiquitous tag 'innit' is believed to have started among Indians in the West Midlands in the 1970s via 'haina'." This conjecture, however, fails to account for much earlier attestations of innit in British English, which would seem to be a simple shortening of isn't it. Granted, the spread of innit as an invariant tag (meaning that it does not require agreement for person, tense or number) could very well have been helped along by similar tags in the native languages of immigrants to Britain, but according to Peter Trudgill the key influence was from the Caribbean rather than South Asia:

There is an enormous body of literature on the invariant tag innit in English English, The origin appears to be in London-based Caribbean-influenced varieties, where it seems to have served originally as a 'translation' of Caribbean English Creole 'no?". It is worth noticing that such invariant tags are very common in areas where English has a history of being learnt as a second language, e.g Welsh English invariant "isn't it?"; broad South African English "is it?"; West African English "is it?", Indian English "isn't it?"; Singaporean English "isn't it? / is it?"

In any case, I'm pretty sure that Hindi hai na has no connection to northeastern Pennsylvania's heyna, but we might want to check with Kelly Kapoor.

[Update #1: Craig Close points out some blog synchronicity: on the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel's Word to the Wise blog, Tom Tolan discusses ain(n)a, a remnant of Milwaukee's German settlers. Tolan writes:

My favorite short explanation of where aina came from I found in an article online about German-American dialect songs, by University of Wisconsin-Madison professor James Leary. He writes: "'Aina' or 'Enna,' from the English 'ain't' and the German 'ne' (a dialect rendering of 'nicht'), is a venerable 'Milwaukeeism' meaning roughly 'isn't that so?'" (This in a passage about a song called "Aina Hey" by Milwaukee musician Sigmund Snopek III, in which "Snopek chants the phrase over and over, creating a musical and verbal icon of Upper Midwestern Anglo-Germanic fusion — an abstract, modernist dialect song.")

And see Arnold Zwicky's post immediately after this one for a bit more on British innit.]

[Update #2: A nice note from the creators of "Heynabonics":

We can now say "WE'VE MADE IT." We noticed Heynabonics was featured on the U of P Language Log. Whoo Hoo!

Thanks for your great article.

By way of background, Chris O'Donnell is the writer and the 'student' with glasses was born and raised in Wilkes-Barre, the heart of Northeastern Pennyslvania. The 'teacher' Greg Korin, lived in Las Vegas and Montana before moving to NEPA for a radio gig. Shivaun O'Donnell, the female 'student' moved to NEPA to go to college. Born to two Wilkes-Barre residents who'd had the heyna wacked out of them, she spent her first two years in Wilkes-Barre trying to figure out what people were saying.

The other core members of the troupe, Karen Novick, Jack Gibbons and John Schurgard were all born and raised in NEPA.

Thanks again.

Shivaun O'Donnell and all of us at One Laugh at Least.

Also, discussion about heyna and other tag questions has been going on over at Languagehat.]

Posted by Benjamin Zimmer at November 17, 2007 05:14 PM