December 01, 2007

American Indian hyphens

A few days ago, Jeffrey Kallberg sent a note asking about the practice of writing American Indian words -- especially proper names -- with multiple internal hyphens.

I write with a query having to do with a current project of mine on Chopin's Berceuse, as it might relate to the composer's broader world view in the 1840s.

The essay deals in part with Chopin's interest in a group of Ioway (Baxoje) Indians "exhibited" in Paris by George Catlin; Chopin may have visited two of the Ioway himself, in the company of George Sand, who was particularly taken with the native Americans (she wrote a long essay about them). And he certainly read a number of the articles about them that appeared in the Parisian press.

In a letter to his family, echoing the practice found in all the press accounts I've seen, he gives the names of the husband and wife as "Shin-ta-yi-ga" and "Oké-wi-me." There are variant spellings of the individual syllables of these names, but the names themselves always appear in this hyphenated form.

My question has to do with the history of this hyphenating practice. I assume that it derives from the practices of the various Western missionaries and explorers who first documented their encounters with the native Americans. And I presume equally that the hyphens have little do with Baxoje self-representation. Has anyone written about why hyphens came to be used so prominently in writing the names of native Americans? It obviously draws attention to the "unusual" (to Western eyes) syllables - but you don't see this (I think) when people write about "unusual" eastern European names (to take one area I know pretty well).

Prof. Kallberg relays a hypothesis:

A colleague who works on native American (and Canadian) music opined that European notions of "primitive" culture might lead them to think that the language they encountered had only monosyllabic words. (She noted that she didn't know of any Native American languages with short words since most are polysynthetic -- making whole sentences by adding syllables into the middle of words). Hence the hyphens may have been a means of marking what they thought were word divisions.

Gene Buckley commented:

I've always thought this was a holdover from the 19th-century style of phonetic transcription, such as that in John Wesley Powell's "Introduction to the Study of Indian Languages" from 1880. I have copies of a "schedule" from that book -- lists of vocabulary to elicit -- in Alsea (coastal Oregon), and hyphens separate nearly all syllables. I don't have the instructions for the schedule in front of me but I think this practice is specifically advocated. I do have the printed "Indian linguistic families of America north of Mexico" by Powell and he uses hyphens when he gives the native pronunciations of various language names.

Other sources also did this frequently, which is helpful when the phonetic alphabet was fairly primitive and sometimes vulnerable to regular orthographic interpretation. Early transcribers probably sounded things out syllable by syllable anyway. This was the way that many of the languages were first written down, so the hyphenated style at least has tradition behind it, and doesn't require the same linguistic training to interpret as the 20th century transcriptions do.

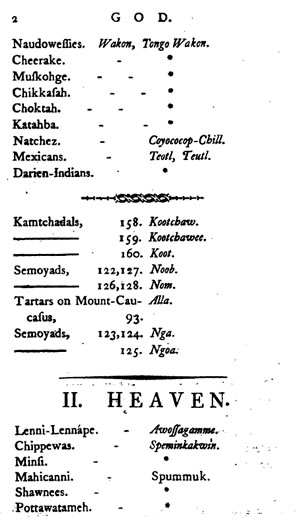

But there's more to it, because earlier sources don't use this style. Thus Benjamin Smith Barton's "New views of the origin of the tribes and nations of America", 1797, contains long vocabulary lists compiled from multiple sources, in which hyphens are quite rare. Here's p. 2 of his word lists, for example:

The same is true for the word lists in Alexander MacKenzie's 1793 journal, described in Bill Poser's post "Words from the West" (9/27/2004).

After a very short search, the earliest hyphenated examples that I've been able to find are in John Tanner's 1830 work A Narrative of the Captivity and Adventures of John Tanner (U.S. Interpreter at the Saut de Ste. Marie) During Thirty Years Residence Among the Indians in the Interior of North America (1830). Thus the subheading to Chapter 1 reads:

Recollections of early life -- capture -- journey from the mouth of the Miami to Sa-gui-na -- ceremonies of adoption into the family of my foster parents -- harsh treatment -- transferred by purchase to the family of Net-no-kwa -- removal to Lake Michigan.

Describing his abduction by a Shawnee band at the age of nine, he writes:

The Indians who seized me were an old man and a young one; these were, as I learned subsequently, Manito-o-gheezhik, and his son Kish-kau-ko.

So apparently the hyphenation practice arose at some time between Barton's book in 1797 and Tanner's book in 1830.

As in the original examples "Shin-ta-yi-ga" and "Oké-wi-me", Tanner's hyphenation is usually syllable-by-syllable but sometimes not. (Another example from Tanner with a polysyllabic part: the name Taw-ga-we-ninne. ) This seems most likely to be meant to represent morphological division; but perhaps it sometimes reflects some perceived difference in prosody.

Some words are left entirely unhyphenated. In some cases, this might be because they are treated as having been borrowed into English. Thus:

The kindness of this family of Tus-kwaw-go-mees continued as long as we remained near them. Their language is like that of the Ojibbeways, differing from it only as the Cree differs from that of the Musk-ke-goes.

But there are other unhyphenated examples that do not seem plausibly to be borrowings:

Lakes of the largest class are called by the Ottawwaws, Kitchegawme; of these they reckon five; one which they commonly call Ojibbeway Kitchegawme, Lake Superior, two Ottawwaw Kitchegawme, Huron and Michigan, and Erie and Ontario. Lake Winnipeg, and the countless lakes in the north-west, they call Sahkiegunnun.

Hyphenation is sometimes applied to common nouns as well as proper nouns:

...The sugar trees, called by the Indians she-she-ge-ma-winzh, are of the same kind as are commonly found in the bottom lands on the Upper Mississippi, and are called by the whites "river maple".

Whatever the explanation for Tanner's hyphenation choices, it does not seem likely to have been a difficulty in determining pronunciation, or a misapprehension about the nature of the morphemes involved, as he lived among Indians as one of them for more than 30 years, and then worked as an interpreter.

If you know anything more about the origins and spread of this orthographic practice, please tell me.

[Update -- David Eddyshaw writes:

Might this be connected with the practice one sees in old-fashioned King James Versions of the Bible, of similarly splitting up Hebrew (and even Greek) names, eg Sol-o-mon, Je-sus, Neb-u-chad-nez-zar, The-oph-i-lus?

I'm fairly sure this is goes back to the nineteenth century, but I can't quote chapter and verse to prove it (uurgh).

The original KJV was not hyphenated this way. I'm not sure which later editions might have followed such a practice. ]

[A bit of Google Scholar search turns up Lonnie Underhill's "Indian Name Translation" (American Speech 43(2) 114-126 1968). Underhill cites a 1902 directive from the Commissioner of Indian affairs including 10 rules about the use of Indian names, of which number 6 is:

Spell the names, whether Indian or translated, as one word, and do not use hyphens, as Onehatchet or Miahvis.

The same paper contains a number of interesting anecdotes about hyphenated phrasal names, e.g.

One case arose on the Pawnee Reservation, Oklahoma, where an indian was named Coo-rux-rah-ruk-koo. Commonly he was known as Afraid-of-a-bear. A literal translation of his Indian name was "fearing a bear that is wild." From this translation the agent recorded him as Fearing B. Wilde.

However, Underhill doesn't tell us where or when the practice of hyphenation arose.

The hyphenation of phrasal names in translation can be seen in many late nineteenth and early twentieth century works, for instance Rudyard Kipling's "How the first letter was written":

ONCE upon a most early time was a Neolithic man. He was not a Jute or an Angle, or even a Dravidian, which he might well have been, Best Beloved, but never mind why. He was a Primitive, and he lived cavily in a Cave, and he wore very few clothes, and he couldn't read and he couldn't write and he didn't want to, and except when he was hungry he was quite happy. His name was Tegumai Bopsulai, and that means, 'Man-who-does-not-put-his-foot- forward-in-a-hurry'; but we, O Best Beloved, will call him Tegumai, for short. And his wife's name was Teshumai Tewindrow, and that means, 'Lady-who-asks-a-very-many-questions'; but we, O Best Beloved, will call her Teshumai, for short. And his little girl-daughter's name was Taffimai Metallumai, and that means, 'Small-person-without-any-manners-who-ought-to-be-spanked'; but I'm going to call her Taffy. And she was Tegumai Bopsulai's Best Beloved and her own Mummy's Best Beloved, and she was not spanked half as much as was good for her; and they were all three very happy. As soon as Taffy could run about she went everywhere with her Daddy Tegumai, and sometimes they would not come home to the Cave till they were hungry, and then Teshumai Tewindrow would say, 'Where in the world have you two been to, to get so shocking dirty? Really, my Tegumai, you're no better than my Taffy.

]

[A bit more searching has antedated the use of hyphens in American Indian names by a bit, to Edwin James, "Account of An Expedition From Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains, Performed in the Years 1819, 1820 ... ", published in 1823. James occasionally uses hyphens, mostly (as far as I have seen) in contexts where he is apparently intending to give morphological divisions. At least, he seems to use hyphenated forms whenever he also gives a translation, and not otherwise. Thus from Chapter X ("Account of the Omawhaws. -- Their manners and customs, and religious rites. ..."):

When the guests are all arranged, the pipe is lighted, and the indispensable ceremony of smoking succeeds.

The principal chief, Ongpatonga, then rises, and extending his expanded hand towards each in succession, (see Language of Signs, no. 43. App. B.) gives thanks to them individually by name, for the honour of their company, and requests their patient attention to what he is about to say. He then proceeds somewhat in the following manner. "Friends and relatives: we are asembled here for the purpose of consulting respecting the proper course to pursue in our next hunting excursion, wor whether the quantity of provisions at present on hand, will justify a determination to remain here to weed our maize. If it be decided to depart immediately, the subject to be then taken into view will be the direction extent, and object of our route; whether it would be proper to ascend Running-Water creek, (Ne-bra-ra, or Spreading water), or the Platte, (Ne-bres-kuh, or Flat water), or hunt the bison between the sources of those two streams; [...]

When Ongpatonga is first introduced, in an earlier chapter, he too is hyphenated as well as translated (p. 155):

On the 14th of October, four hundred Omawhaw Indians assembled at Camp Missouri. Major O'Fallon addressed them in an appropriate speech, stating the reasons for their being called to council; upon which Ong-pa-ton-ga, the Big Elk, arose, and after shaking by the hand each of the whites resent, placed his robe of otter skins, and his mockasins under the feet of the agent, whom he addressed to the following effect, as his language was interpreted by Mr. Dougherty.

]

[Barbara Zimmer writes to remind us of the connection to Hiawatha, which was was written a bit later than Chopin's letter, but was based on sources published slightly earlier:

Obviously the romance of the Native Americans and their various languages influenced Longfellow who started his poem Hiawatha in 1854; it was completed and published in 1855.

Longfellow obtained much of his knowledge from legends and stories collected by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft who was superintendent for Indian Affairs for the state of Michigan from 1836 to 1841. From an introduction to Hiawatha available online:

Schoolcraft married Jane, O-bah-bahm-wawa-ge-zhe-go-qua (The Woman of the Sound Which the Stars Make Rushing Through the Sky) Johnston. Jane was a daughter of John Johnston, an early Irish fur trader, and O-shau-gus-coday-way-qua (The Woman of the Green Prairie), who was a daughter of Waub-o-jeeg (The White Fisher), who was Chief of the Ojibway tribe at La Pointe, Wisconsin.

Jane and her mother are credited with having researched, authenticated, and compiled much of the material Schoolcraft included in his Algic Researches (1839) and a revision published in 1856 as The Myth of Hiawatha. It was this latter revision that Longfellow used as the basis for The Song of Hiawatha.

From another online article about Longfellow's poem "Hiawatha" we can see a chart of many of the words that Longfellow used, and can learn that

Though Hiawatha is an Iroquois hero, Longfellow's poem is set in Minnesota, and most of the Native American words he uses in it come from the Minnesota Indian languages Ojibwe (Chippewa) and Dakota Sioux. The story Longfellow relates, too, is primarily based not on the Iroquois legend of Hiawatha but rather on the Chippewa legend of Nanabozho, a rabbit spirit who was the son of the west wind and raised by his grandmother.

Like James' Account of an Expedition..., is available for full download from Google Books. ]

[James Crippen writes:

The "dread hyphen disease", as I call it, affected even the Russians in Russian America (later Alaska). The American Russian Orthodox Church has been digitally retypesetting documents in several Alaska Native languages from the 19th century, including the language I study, Tlingit. The document below was purportedly published in 1901 but was probably composed much earlier given the low sophistication of the Tlingit transcription. Much better ones were published in 1846, so this is probably earlier than that.

http://www.asna.ca/alaska/tlingit/indication-pathway-part-1.pdf

For the 1846 document, see:

http://www.asna.ca/alaska/research/zamechaniya.pdf

I'm still working out how the orthography in each of the Cyrillic Tlingit documents was structured.

]

Posted by Mark Liberman at December 1, 2007 07:13 AM