February 01, 2008

Incorrections in the newsroom: Cupertino and beyond

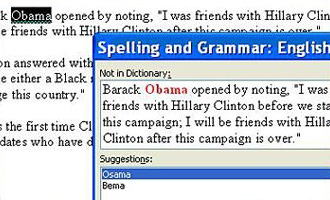

Many of the journalistic "incorrections" we've noted here recently, from the "Muttonhead Quail Movement" to "GOP cell phones," can be blamed on the inattentive use of spell-checkers, otherwise known as the Cupertino effect. Thierry Fontenelle of the Microsoft Natural Language Group gave us some insight into efforts on the programming side to improve the advice given by spell-checkers, such as the addition of new words to the speller dictionary, as MySpace was added to the Office 2007 dictionary. And Mark Liberman was recently told by Fontenelle that Obama has been added by Microsoft, available as a part of an update to Office 2003 or 2007. But as Nitya Venkataraman of ABC News now reports, those who haven't updated Office 2007 will get an unfortunate first suggestion for Obama: Osama. A Microsoft PR representative went into damage-control mode, explaining to Venkataraman that the Office spell-checker is not "specifically targeted towards the word 'Obama' to change it to 'Osama.' Instead, the spell-checker just didn't have 'Obama' in its dictionary, so it tried to provide alternative suggestions based on closest match."

Many of the journalistic "incorrections" we've noted here recently, from the "Muttonhead Quail Movement" to "GOP cell phones," can be blamed on the inattentive use of spell-checkers, otherwise known as the Cupertino effect. Thierry Fontenelle of the Microsoft Natural Language Group gave us some insight into efforts on the programming side to improve the advice given by spell-checkers, such as the addition of new words to the speller dictionary, as MySpace was added to the Office 2007 dictionary. And Mark Liberman was recently told by Fontenelle that Obama has been added by Microsoft, available as a part of an update to Office 2003 or 2007. But as Nitya Venkataraman of ABC News now reports, those who haven't updated Office 2007 will get an unfortunate first suggestion for Obama: Osama. A Microsoft PR representative went into damage-control mode, explaining to Venkataraman that the Office spell-checker is not "specifically targeted towards the word 'Obama' to change it to 'Osama.' Instead, the spell-checker just didn't have 'Obama' in its dictionary, so it tried to provide alternative suggestions based on closest match."

Venkataraman bemoans the fact that harried campaign reporters are "one careless spell-check away" from turning Obama into Osama. But it's not just word-processing spell-checkers that can cause trouble for journalists editing their work under deadline pressure. There are other types of automatic replacement than can lead to incorrection, when a global search-and-replace is conducted to conform to a news outlet's style policies. There's an old story that a newspaper once published an article using the expression "back in the African American," presumably due to a politically correct search-and-replace on the word black. According to the urban legend trackers at alt.folklore.urban, the Fresno Bee did actually run an article with "back in the African-American" in 1990, but it turns out it was more of a practical joke than an automated "correction." Nonetheless, there have been a few recent examples where this sort of stylistic search-and-replace has wreaked havoc on published news reports.

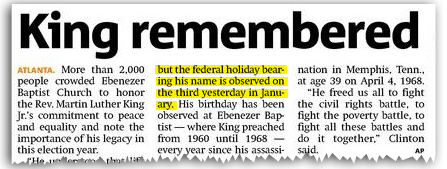

M.C. De Marco brings to my attention one such case, in the Jan. 22 edition of the Boston Metro, a free daily newspaper. As noted on the Random Squeegee blog, an article about the observation of Martin Luther King Day explained that "King's birthday is Jan. 15, but the federal holiday bearing his name is observed on the third yesterday in January."

It looks like what happened here is that the Metro, which relies heavily on wire reports for its news content, was making sure that any story mentioning "Monday" would be changed to "yesterday" for the Tuesday paper. So someone went a little too far with the search-and-replace, altering a "Monday" that was not in fact the day before that Tuesday. Thus the deictically grounded use of "yesterday" was entirely inappropriate, leading to a bit of gibberish. ("For the record, the third yesterday in January is January 2," observes John of Random Squeegee.)

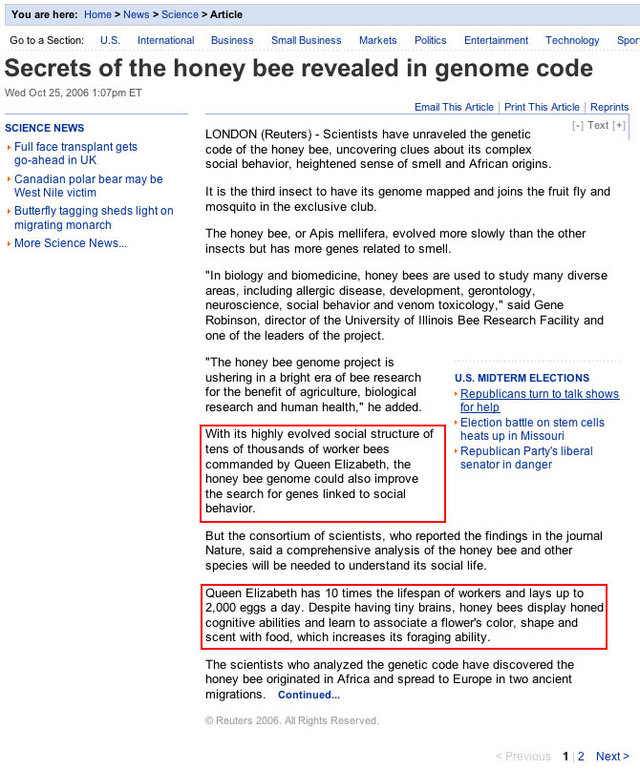

A more startling search-and-replace gaffe turned up in an October 2006 Reuters article about honey bees. The eagle-eyed folks at Regret The Error got a screenshot before it was corrected:

Reuters style apparently avoids mentions of "the Queen" (of England, that is), instead favoring the full name "Queen Elizabeth." But that rule of thumb is of course very misguided when applied to a sentence like "The queen has 10 times the lifespan of workers and lays up to 2,000 eggs a day." British tabloid media had a field day with this one, but they should know better: any journalist can fall victim to the perils of search-and-replace.

Posted by Benjamin Zimmer at February 1, 2008 11:54 PM