October 11, 2003

Emergence of birdsong phonology

It's like watching life emerge from the primordial ooze. Ofer Tchernichovski at CCNY has produced some amazing animations of the dynamics of birdsong development.

Ofer studies song learning in zebra finches -- here is some background information, and here is a 2001 Science paper by Ofer and others (requires a subscription).

Ofer raises the birds in a controlled environment -- made from beer coolers! -- so that he can specify everything that they hear, and record every sound they make, over a period of months.The recorded songs are automatically detected and segmented into "syllables" with fairly high accuracy, and the individual syllables are automatically characterized in in terms of 12 acoustic properties like duration, average pitch, amount of frequency modulation, and so on. The result is a sequence of many millions of feature vectors for each bird, representing its entire vocal output over the time when it is learning and mastering its song.

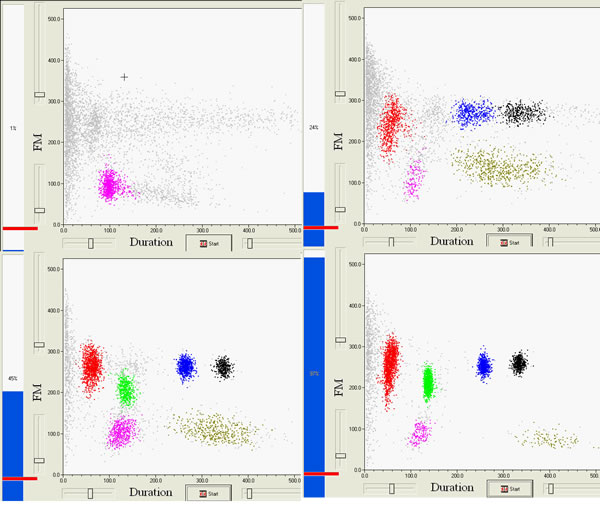

At the end, the bird's song is a sequence of complex "syllables," which are individually very different from one another in repeatable ways, and are produced in a stereotyped (though not invariant) order. In the beginning, the bird's "proto-song" is a series of proto-syllables that seem to have less individual structure, and are more variable in their properties and less well differentiated from one another.

Each frame of one of Ofer's movies shows a few thousand syllables from a given bird, plotted on a couple of dimensions such as duration and amount of frequency modulation. These dimensions don't give a complete picture of a syllable's sound by any means, but they express some of its properties that seem to be important. The sequence of frames in the movie follows the progression of time over the 100 days or so that it takes the bird to master its song completely.

The picture below shows four frames from the beginning, middle and end of such a movie, arranged left-to-right and top-to-bottom. The blue bar on the left of each frame shows the progression through 100 days of the bird's life, starting before first exposure to an adult song model, and ending after full mastery of the song. The colors in the scatter plots are automatically assigned by a clustering algorithm.

In some sense, we're seeing symbols emerge from signals. The syllable clusters are not "symbols" in the strong sense of "signs with meanings"; but they are symbols in the weaker sense, a finite set of well-differentiated types to which behavioral tokens belong. The fully-developed song then functions for some purposes as a sequence of syllable types, independent of the variable details of their performance. The zebra finch audience probably responds to virtuosity and perhaps to other aspects of performance variation, but birdsong (like human speech) develops "phonological" categories that clearly play a central role in organizing the behavior.

Why? In human spoken language, Hockett's "duality of patterning" is a plausible evolutionary motivation: if you want to have a vocabulary of a hundred thousand items with good transmission fidelity, the coding had better be digital. But these birds don't connect particular "syllable" sequences with particular meanings, and in fact a zebra finch only has one song, whose meaning Ofer glosses as "I love you" when it is directed to a female, and "get lost" when it is directed to another male. Does their system "go digital" just as a side-effect of the need to create signals that are impressively complex from the perspective of other birds?

The movie is much more compelling than the excised frames; I'll ask Ofer if he can post it somewhere.

Update -- here it is:

Posted by Mark Liberman at October 11, 2003 08:24 PM