June 04, 2004

Writing System Reform

People sometimes wonder why we couldn't reform the awful English spelling system. Some of the relevant factors are:

- People want those who come after them to suffer the same way they did.

- The ability to spell correctly serves as a sign of social class. If spelling were easy, this marker would not be available.

- Those who learn to read in a revised system would have difficulty reading everything published prior to the reform.

- The market for spellcheckers and monolingual dictionaries would be greatly reduced.

- Spelling bees would disappear.

There has been debate in Japan about whether Chinese characters should be eliminated, replaced by the exclusive use of ひらがな [hiragana] and カタカナ [katakana] or by roman letters, since the late 19th century. After the Second World War the push for romanization became particularly intense. At one point, it seemed likely that the Occupation authorities would impose romanization. A spelling reform did in fact take place, but it just reduced the number of Chinese characters in official use, simplified the form of many characters, and eliminated historical spellings. For instance, 行こう [iko:] "let's go" used to be written 行かむ [ikamu], which is how it was actually pronounced some hundreds of years ago.

[For the curious, what happened is that the /m/ dropped out. Then the /a/ and the /u/ merged into a long [ɔ:]. At this point Japanese had five short vowels but six long vowels, with a contrast between [ɔ:] and [o:]. After a while, [ɔ:] merged with [o:]. The same changes explain why the city of Kobe [ko:be] is written 神戸, which we would expect to pronounce [kamibe]. Actually, you'd probably expect it to be [kamito] or [kamido], but for simplicity's sake we'll assume that you already know that 戸 is pronounced [he] in some placenames, and of course you know that [he] is likely to become [be] at the beginning of the second member of a compound noun. First [kamibe] became [kamube]. Then the changes just described led from [amu] to [o:].]

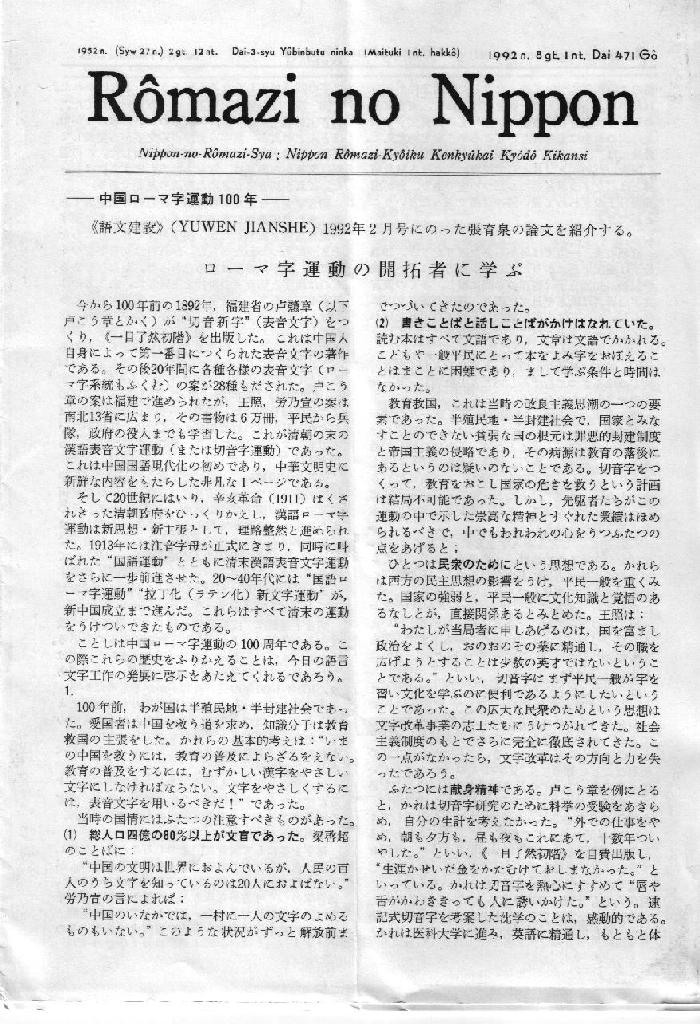

Although it seems very unlikely that Japan will shift to romanization, there is still an organization that promotes the use of romanization, the Japanese Romanization Society. You can easily see how unlikely the Society is to attain its goal by looking at its newsletter, and you don't even have to be able to read Japanese. Here is the first page of the issue of August 1, 1992, which I happen to have on hand. The lead article celebrates the centennial of the Chinese romanization movement. I used to be on their mailing list, but I guess I fell off it due to moving around.

As you can see, most of the page is in the usual Japanese mixture of Chinese characters and kana. I'd say that of the issues I've read, not one was more than 50% in romanization. That isn't because anyone would be unable to read it. All Japanese learn romanization in Grade Five and also study English. Even the Romanization Society can't quite bring itself to make the change.

Posted by Bill Poser at June 4, 2004 01:32 AM