November 25, 2004

Thanks Giving

Revisionists and debunkers are fond of noting the Thanksgiving holiday's history of blood, failure and fakery. Despite this, it's my favorite holiday, one of the many valuable tributes that vice pays to virtue. In addition to whatever contemporary blessings of family, health and prosperity we may enjoy, we can be thankful for the lessons of the associated history, in its darker as well as its nobler aspects.

The history really starts in 1827, or perhaps in 1863, as much as in 1621:

The establishment of the day we now celebrate nationwide was largely the result of the diligent efforts of magazine editor Sarah Josepha Hale. Mrs. Hale started her one-woman crusade for a Thanksgiving celebration in 1827, while she was editor of the extremely popular Boston Ladies’ Magazine. Her hortatory editorials argued for the observance of a national Thanksgiving holiday, and she encouraged the public to write to their local politicians.

In addition to her magazine outlet, over a period of almost four decades she wrote hundreds of letters to governors, ministers, newspaper editors, and each incumbent President. She always made the same request: that the last Thursday in November be set aside to "offer to God our tribute of joy and gratitude for the blessings of the year."

Finally, national events converged to make Mrs. Hale’s request a reality. By 1863, the Civil War had bitterly divided the nation into two armed camps. Mrs. Hale’s final editorial, highly emotional and unflinchingly patriotic, appeared in September of that year, just weeks after the Battle of Gettysburg, in which hundreds of Union and Confederate soldiers lost their lives. In spite of the staggering toll of dead, Gettysburg was an important victory for the North, and a general feeling of elation, together with the clamor produced by Mrs. Hale’s widely circulated editorial, prompted President Abraham Lincoln to issue a proclamation on October 3, 1863, setting aside the last Thursday in November as a national Thanksgiving Day.

However, Mrs. Hale was by no means the first post-colonial American to suggest a national day of thanksgiving. In 1808, the Rev. Samuel Miller asked Thomas Jefferson to proclaim a national thanksgiving day devoted to fasting (!) and prayer. Whatever our opinion on the legal issues involved, we should be grateful that Jefferson refused:

I consider the government of the U S. as interdicted by the Constitution from intermeddling with religious institutions, their doctrines, discipline, or exercises. ... But it is only proposed that I should recommend, not prescribe a day of fasting & prayer. That is, that I should indirectly assume to the U.S. an authority over religious exercises which the Constitution has directly precluded them from. It must be meant too that this recommendation is to carry some authority, and to be sanctioned by some penalty on those who disregard it; not indeed of fine and imprisonment, but of some degree of proscription perhaps in public opinion. And does the change in the nature of the penalty make the recommendation the less a law of conduct for those to whom it is directed? I do not believe it is for the interest of religion to invite the civil magistrate to direct its exercises, its discipline, or its doctrines; nor of the religious societies that the general government should be invested with the power of effecting any uniformity of time or matter among them. Fasting & prayer are religious exercises. The enjoining them an act of discipline. Every religious society has a right to determine for itself the times for these exercises, & the objects proper for them, according to their own particular tenets; and this right can never be safer than in their own hands, where the constitution has deposited it.

Though doubtless beneficial to our spiritual and physical health, a Thanksgiving of fasting rather than feasting would emphasize the cramped and defensive tendencies in American culture, instead of the generous and optimistic side. (And I doubt that it would be a very popular holiday...)

Despite the Puritan's reputation for asceticism, when they invited Massasoit (Grand Sachem of the Wampanoag) to celebrate their first harvest, it was not for fasting. The feast lasted for three days, even though neither group at that point had a lot to celebrate at that point other than lack of total extermination. The food was prepared by the four adult women among the colonists who had survived the previous year -- thirteen others had died of cold, starvation and disease. And by 1621 the mainland Wampanoag had been nearly wiped out by "three epidemics which swept across New England and the Canadian Maritimes between 1614 and 1620", reducing their population from 8,000 to about 2,000. The resulting conflicts made their situation even more precarious:

For the Wampanoag, the ten years previous to the arrival of the Pilgrims had been the worst of times beyond all imagination. Micmac war parties had swept down from the north after they had defeated the Penobscot during the Tarrateen War (1607-15), while at the same time the Pequot had invaded southern New England from the northwest and occupied eastern Connecticut. By far the worst event had been the three epidemics which killed 75% of the Wampanoag. In the aftermath of this disaster, the Narragansett, who had suffered relatively little because of their isolated villages on the islands of Narragansett Bay, had emerged as the most powerful tribe in the area and forced the weakened Wampanoag to pay them tribute.

Massasoit, therefore, had good reason to hope the English could benefit his people and help them end Narragansett domination.

The alliance with the English seems to have worked out for a decade or so:

To the Narragansett all of this friendship between the Wampanoag and English had the appearance of a military alliance directed against them, and in 1621 they sent a challenge of arrows wrapped in a snakeskin to Plymouth. Although they could barely feed themselves and were too few for any war, the English replaced the arrows with gunpowder and returned it. While the Narragansett pondered the meaning of this strange response, they were attacked by the Pequot, and Plymouth narrowly avoided another disaster. The war with the Pequot no sooner ended than the Narragansett were fighting the Mohawk. By the time this ended, Plymouth was firmly established. Meanwhile, the relationship between the Wampanoag and English grew stronger. When Massasoit became dangerously ill during the winter of 1623, he was nursed back to health by the English. By 1632 the Narragansett were finally free to reassert their authority over the Wampanoag. Massasoit's village at Montaup (Sowam) was attacked, but when the colonists supported the Wampanoag, the Narragansett finally were forced to abandon the effort.

However, the events subsequent to 1632 gave the Wampanoag little reason to celebrate:

As more British colonists arrived in Massachusetts, they began displacing Wampanoag people from their traditional lands, particularly by plying them with alcohol and obtaining their signatures on land sale documents while they were drunk. The Wampanoag leader Metacomet, known as "King Philip" to the English, tried to get this practice outlawed, and when the British refused, a war ensued. The British won decisively, sold many of the Wampanoag survivors into slavery, drove the rest into hiding, and forbade the use of the Massachusett language and Wampanoag tribal names.

As I understand this history, the English colonists were no more violent, aggressive or dishonest than the other groups competing for domination in the area; but they were more numerous and somewhat more advanced in the technologies of both war and peace, and their growth overwhelmed the nations who had been there before them.

The archives of the American Philosphical society include a recording of a prayer in Wampanoag, made in 1961 by the last semi-speaker. No transcript is provided. According to the Ethnologue entry for Wampanoag, there was a bible translation done in 1663-1685, which is discussed at greater length in this page about Harvard's "Indian College":

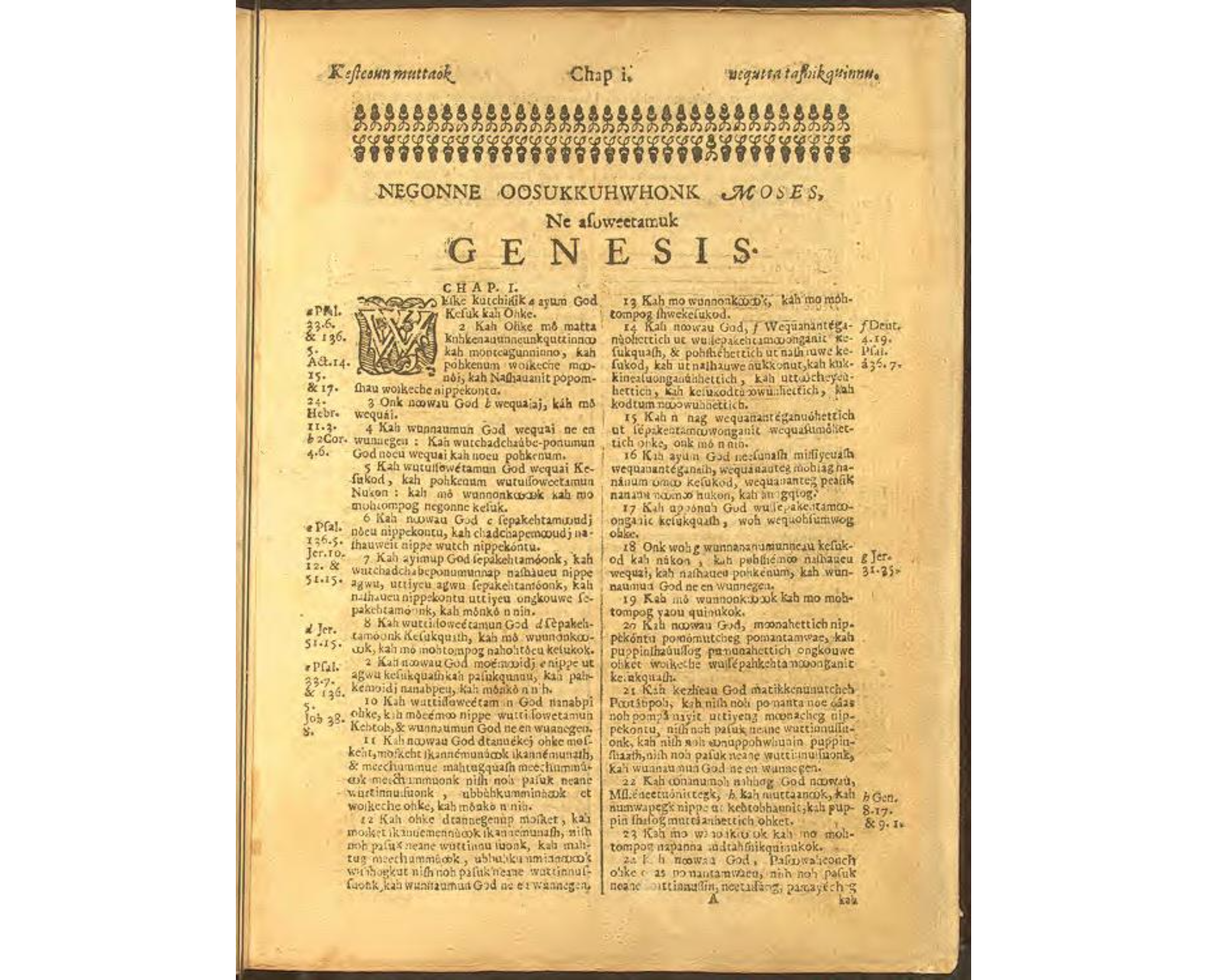

In 1655, Harvard completed building the Indian College — a two-story brick structure intended to house twenty scholars. The Indian College was the fourth building erected in the “Yard” and was situated near the southern end where Matthews Hall now stands. Within the new Indian College, Harvard installed a press that had previously been housed in the College president's house since 1638. From 1661 to 1663, John Eliot, "the Apostle to the Indians," printed a translation of the Bible into the Wampanoag language-- the first Bible printed in North America. John Eliot's translation remained in use some 200 years later. Between 1655 and 1672, printing presses at the Indian College produced books and pamphlets, along with primers, catechisms, grammars, and tracts— one-eighth of which were in Wampanoag. James Printer, a Nipmuc Indian who had attended Harvard several decades earlier, worked the presses.

Despite this apparently promising multicultural beginning, the "Indian College" seems to have matriculated only five native students, only one of whom graduated, and the building was torn down in 1693, 50 years before Thomas Jefferson was born.

This page gives some further information on the John Eliot's Indian Bible, entitled Mamvsse wunneetupanatamwe up-biblum God naneeswe nukkone testament kah wonk wusku testament / ne quoshkinnumuk nashpe wuttinneumoh Christ noh asoowesit John Eliot, nahohtoeu ontchetoe printeuoomuk. Cambridge [Mass.] : Printeuoop nashpe Samuel Green, MDCLXXXV:

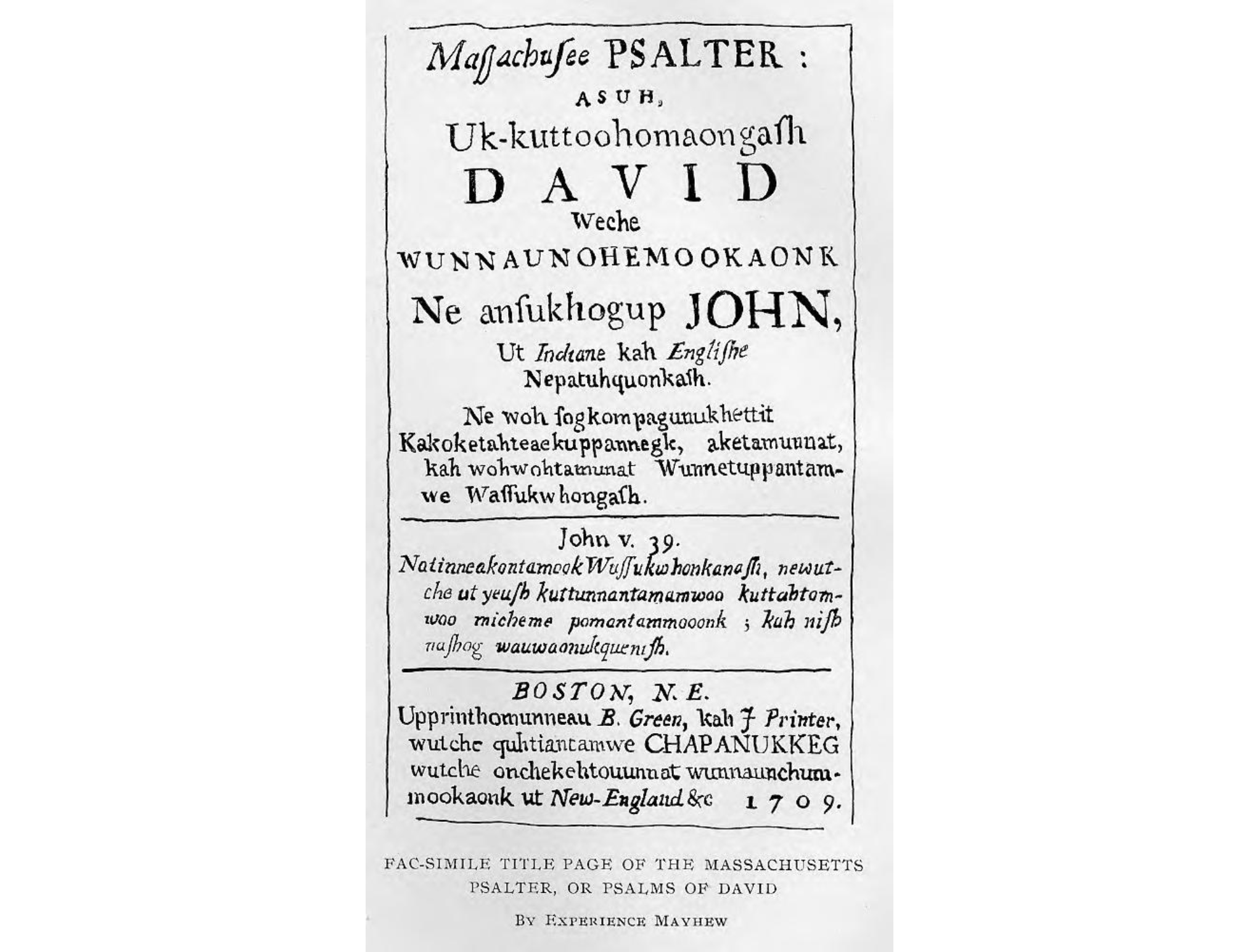

and The Massachuset Psalter, or, Psalms of David : with the Gospel according to John : in columns of Indian and English : being an introduction for training up the aboriginal natives in reading and understanding the Holy Scriptures. Boston, N.E. : Printed by B. Green and J. Printer for the honourable Company for the Propagation of the Gospel in New-England, 1709 (translated by Experience Mayhew):

The only federally-recognized Wampanoag group today is the Wanpanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah), living on the western end of Martha's Vinyard, at the opposite end of the island from Chappaquiddick. Other organized bands include Assonet, Herring Pond, Mashpee, and Namasket, with a total membership of about 3,000.

Posted by Mark Liberman at November 25, 2004 10:12 AM