July 26, 2005

The the the and the thee the

Turns out people reduce the and a a lot. In case we doubted it, Mark showed us here, here, here, here and here. But when do speakers produce the fully articulated form, and when do they reduce?

For the, Jean Fox Tree and Herb Clark found the answer back in 1997: speakers mostly use the full form when they can't figure how to say whatever the hell they want to say next, and otherwise they say thuh. An extended theeeee (...uhhh...) may be both a way of biding time while you figure out that troublesome word or phrase, and a way of telling your audience "bear with me a moment: I'm about to say something so amazingly surprising even I can't figure out what it is. No really, it's gonna be absolutely fascinating. Nearly there now, I've totally focused all available neural circuitry on producing something special just for you, so please give me a few centiseconds more of processing time... you're starting to look distracted, but this is *definitely* going to be worth the wait... ok, here it comes...."

So the is normally reduced, but tends to occur with a full vowel, or even a greatly extended vowel, when the speaker is having difficulty planning or producing a following constituent. Furthermore, there's evidence that hearers use this information in real time.

The Fox Tree and Clark abstract gives a good idea of what's in the paper:

| Jean Fox Tree and Herb Clark, Pronouncing "the"

as "thee" to signal problems in speaking, Cognition 62 (1997) 151 - 167. Abstract: In spontaneous speaking, the is normally pronounced as thuh, with the reduced vowel schwa (rhyming with the first syllable of about). But it is sometimes pronounced as thiy, with a nonreduced vowel (rhyming with see). In a large corpus of spontaneous English conversation, speakers were found to use thiy to signal an immediate suspension of speech to deal with a problem in production. Fully 81% of the instances of thiy in the corpus were followed by a suspension of speech, whereas only 7% of a matched sample of thuhs were followed by such suspensions. The problems people dealt with after thiy were at many levels of production, including articulation, word retrieval, and choice of message, but most were in the following nominal. |

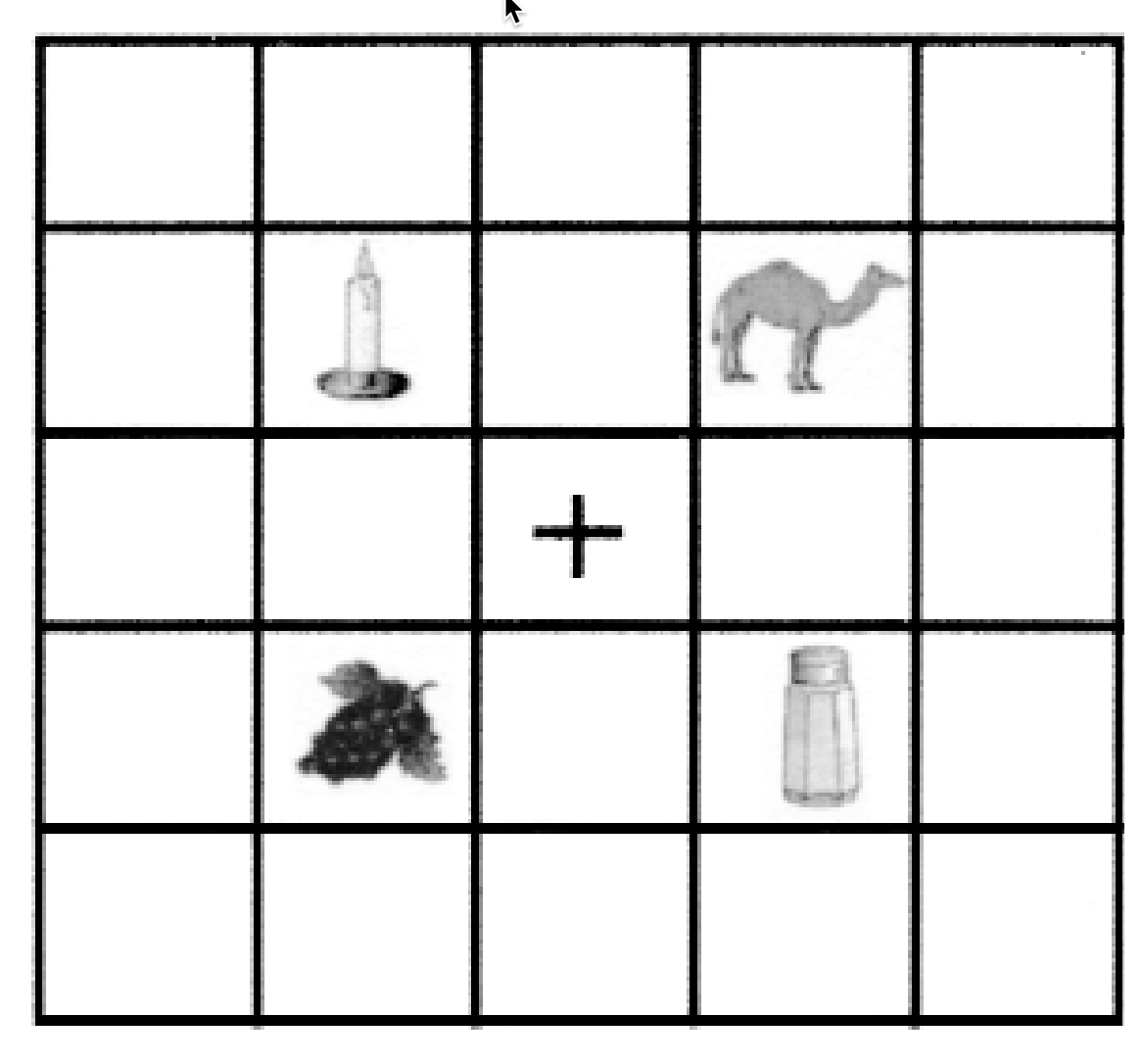

Clark and Fox Tree think use of full or extended the is a signal (albeit not one we are normally consciously aware of) given by the speaker as part of the coordination game played by conversational participants. Elsewhere on Language Log we discussed a similar argument from Clark and Fox Tree that speakers use uh and um as signals. But can hearers use such subtle indications? Jennifer Arnold, Maria Fagnano, and Michael Tanenhaus later provided evidence that hearers are quite sensitive to this sort of signalling (Disfluencies Signal Theee, Um, New Information, Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, Vol. 32, No. 1, January 2003). Here's a picture they used in their experiment:

When hearers looking at the picture above (and wearing eye-tracking devices) are asked e.g. to put theee uhh camel below the salt shaker, the theee uhh (as opposed to simple thuh) leads them to move their eyes to previously unmentioned objects. Presumably, this strategy is based on an assumption that the speaker is more likely to have processing difficulty when saying something new than when talking about something previously mentioned. So we can use a signal of processing difficulty to help us predict the meaning of an as yet unsaid word. Who'da thought?

I don't know of any equivalent results for full vs. reduced a, but I'll stick my neck out and guess that occurrences of full a correlate to some extent with following disfluencies.

All of this supports Mark's attempt to turn on its head the idea that reduced the/a is a sign of sloppiness. On the contrary, in fluent speech the and a are reduced: it's full renditions of the and a which, at least sometimes, indicate that the speaker is in trouble. That's not to say that full renditions are always bad. Perhaps the very nice full a Mark discusses here in George Vecsey of the NYT's phrase he goes out as a great champion with a clean record is an indication of processing difficulty, but perhaps it isn't. Maybe Vecsey just felt like putting clean record into its own intonational phrase for emphasis or contrast, meaning that an a got stuck as the ending to a previous intonational phrase.

Note that the word clean was probably very carefully chosen, given the swirl of unproven doping rumours that suround the seemingly superhuman Armstrong. So a pause before clean may have been needed either to allow Vecsey to conjure the word up in just the right way, or in order to to give it a perceptually distinctive frame in which to sit. Either way, the a would then need to be fully articulated in order to carry what intonational phonologists call a boundary tone, the marker of the end of an intonational phrase. (Technical note: phonologists distinguish between full intonational phrases and smaller units termed intermediate phrases. But I'll ignore that difference here.) Mind you, putting a at the end of an intonational phrase would itself be linguistically interesting, since it implies that Vescey treats he goes out as a great champion with a as an intonational unit. That's notable because some theories of intonation would forbid such a division of the sentence: he goes out as a great champion with a is neither a syntactic constituent nor (more importantly) a semantically natural unit. Then again, and quite informally, I've noticed that radio broadcasters tend to do intonationally weird stuff right at the end of a story, riding slipshod over semantics for the sake of a final rhetorical flourish. Maybe Vescey was doing his best radio voice.

In the interests of full disclosure of anything that might make me seem vaguely important or knowledgeable about this subject, Jean Fox Tree, who's now at UC Santa Cruz, and I were students together way back when in Edinburgh (yeah, ok, so she hadn't started working on the yet, but you know, the vibes were there man), and Herb Clark has an office a mere stone's throw from mine, though the angles would be tough. And Jennifer Arnold is an old friend who was still completing her PhD at Stanford when I arrived as a baby professor. I figure that by mental osmosis I must now be an expert on pronounciations of the. Plus, somewhere I have an LP by The The, or the The The as I like to call them when I meet someone as minutiae minded as me and need to start an argument. And since Mark has now set a tough standard (tough for a semanticist like me anyway) whereby each LL post has to have a new audio segment, here is an innocent little number from my The The album, and here is a complete jukebox of their recordings.

Posted by David Beaver at July 26, 2005 08:09 PM