August 14, 2005

What happened to the 1940s?

There are several different ways to refer to decades -- "the seventies", "the 1970s", and so on. Of these, the textual form YYY0s is the most unambiguous -- a bit of web searching for patterns like {1990s} should convince you that nearly all uses refer to ten-year spans of time rather than to model numbers or the like.

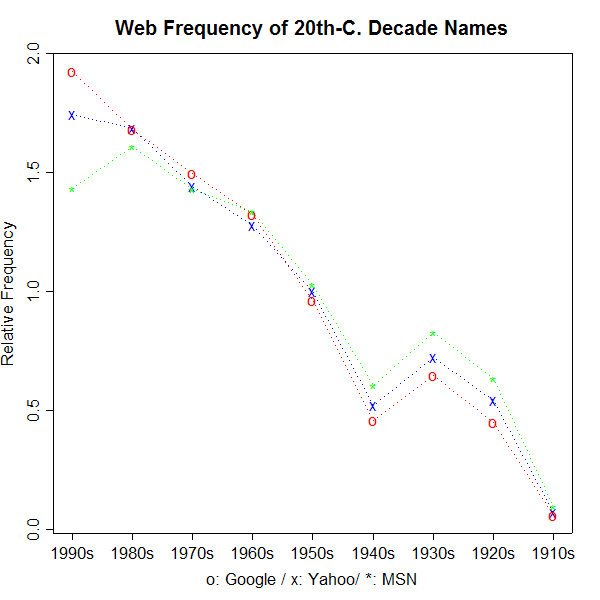

And looking through the counts for the decades of the 20th century shows a main effect of recency: counts decline more or less linearly as the dates move backwards. But there are some divergences from this trend. In particular, the 1940s (and less clearly, the 1910s) are under-represented.

Here the effect is shown graphically:

In order to compare the counts from Google, Yahoo and MSN, I've expressed each search engine's results in terms of ratios to its average for the nine decades cited. The actual counts that I got are given in the table below, in millions. Note that MSN gives exact-seeming counts, while Google and Yahoo give approximations.

Google |

Yahoo |

MSN |

|

| 1990s | 27.4 |

50.1 |

4.524152 |

| 1980s | 23.9 |

48.4 |

5.078620 |

| 1970s | 21.3 |

41.4 |

4.502463 |

| 1960s | 18.8 |

36.7 |

4.219955 |

| 1950s | 13.7 |

28.7 |

3.249855 |

| 1940s | 6.53 |

15.0 |

1.908465 |

| 1930s | 9.19 |

20.8 |

2.609433 |

| 1920s | 6.38 |

15.6 |

2.000209 |

| 1910s | 0.801 |

2.04 |

0.301935 |

The three search engines disagree about the status of the 1990s, but the 1940s and the 1910s are apparently below the trend line in all three counts. Is this because the 1940s and the 1910s were dominated by WW II and WW I respectively? I'm not sure.

I stumbled on this particular oddity because I was setting up to write something about an interesting recent paper by Anatol Stefanowitsch entitled "The function of metaphor" ( International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, Volume 10, Number 2, 2005, pp. 161-198). You can't read it, unless you have a subscription or are willing to pay the extraordinary sum of $37.17 -- a dollar a page plus change -- because, alas, the IJCL is not open access. If you could read the article, you'd find some interesting ideas about using collocational frequencies to explore the functions of metaphorical language. Specifically, Stefanowitsch contrasts what he calls "cognitive" and "stylistic" theories about the nature of metaphor. I thought I'd try to explain the basic issues for people who might not otherwise come across the paper, and especially to describe the methods used, which could be applied much more widely. So I started out to reproduce and extend a couple of Stefanowitsch's test cases, which deal with the distribution of metaphorical (e.g. "the dawn of <time period X>") and literal (e.g. "the beginning of <time period X>") expressions that are more-or-less referentially equivalent.

Stefanowitsch's idea is that we ought to find clues to the nature of the choice between metaphorical and literal expressions by looking at the words that tend to be more closely associated with each of them. He calls these collocational associates "collexemes". Thus with respect to "dawn of" vs. "beginning of", he writes that

...the events and time spans referred to by the collexemes of the literal pattern ... are much shorter and much more clearly delineated than those referred to by the distinctive collexemes of the metaphorical expression ...

I'll save the details (of S's paper and my reactions to it) for another post or two. But as a teaser, here's a bit of the data that I collected for looking at collocations relevant to metaphorical and literal time-period references. S used the British National Corpus, which is only about 100 million words; using the 5-10 trillion words on the web, we can examine some particular semantic fields in much more detail than he did.

For example, we can see that the 21st century is about 35 to 55 times more dawnish than the 18th. This makes metaphorical sense, I guess, but not because the 18th century is either shorter or more clearly delineated:

(Google) "the dawn of the_ " |

(Google) "the beginning of the _" |

(Google) Ratio |

(Yahoo) "the dawn of the_ " |

(Yahoo) "the beginning of the _" |

(Yahoo) Ratio |

(MSN) "the dawn of the_ " |

(MSN) "the beginning of the _" |

(MSN) Ratio |

|

| 21st century | 64,900 |

129,000 |

2.0 |

206,600 |

390,000 |

1.9 |

44,177 |

91,834 |

2.1 |

| 18th century | 466 |

33,600 |

72.1 |

1,280 |

114,000 |

89.1 |

252 |

29,322 |

116.4 |

As another example, the 1960s seem to have been two or three times as dawnish as the 1980s:

(Google) "the dawn of the_ " |

(Google) "the beginning of the _" |

(Google) Ratio |

(Yahoo) "the dawn of the_ " |

(Yahoo) "the beginning of the _" |

(Yahoo) Ratio |

(MSN) "the dawn of the_ " |

(MSN) "the beginning of the _" |

(MSN) Ratio |

|

| 1980s | 831 |

60,500 |

72.8 |

2,530 |

135,000 |

53.4 |

762 |

44,519 |

58.4 |

| 1960s | 983 |

19,500 |

19.8 |

2,410 |

48,100 |

20.0 |

464 |

12,300 |

26.5 |

Again this makes post hoc sense, but again the key is not the concreteness of the time period referenced.

[Update: Rob Malouf writes to draw my attention to Pollmann T. and R.H. Baayen, " Computing Historical Consciousness. A Quantitative Inquiry into the Presence of the Past in Newspaper Texts", Computers and the Humanities, Volume 35, Number 3, August 2001, pp. 237-253(17). From the abstract, it looks relevant and interesting:

In this paper, some electronically gathered data are presented and analyzed about the presence of the past in newspaper texts. In ten large text corpora of six different languages, all dates in the form of years between 1930 and 1990 were counted. For six of these corpora this was done for all the years between 1200 and 1993. Depicting these frequencies on the timeline, we find an underlying regularly declining curve, deviations at regular places and culturally determined peaks at irregular points. These three phenomena are analyzed.

Mathematically spoken, all the underlying curves have the same form. Whether a newspaper gives much or little attention to the past, the distribution of this attention over time turns out to be inversely proportional to the distance between past and present. It is shown that this distribution is largely independent of the total number of years in a corpus, the culture in which it is published, the language and the date of origin of the corpus. The phenomenon is explained as a kind of forgetting: the larger the distance between past and present, the more difficult it is to connect something of the past to an item in the present day. A more detailed analysis of the data shows a breakpoint in the frequency vs. distance from the publication date of the texts. References to events older than approximately 50 years are the result of a forgetting process that is distinctively different from the forgetting speed of more recent events.

Pandel's classification of the dimensions of historical consciousness is used to answer the question how these investigations elucidate the historical consciousness of the cultures in which the newspapers are written and read.

Unfortunately, this is not an open-access journal, and the Penn library doesn't have an electronic subscription to it, nor do I, and I'm not yet curious enough to pay $40 plus tax for a sixteen-page article relevant relevant to a blog post -- nor even to make a special trip to the library stacks].

Posted by Mark Liberman at August 14, 2005 05:10 PM