September 12, 2005

Leading with the chin

Because of recent events in Louisiana, I just re-read Robert Penn Warren's All the King's Men, which I first encountered in high school. I didn't remember much about it, beyond the standard plot summary, and the fact that at fifteen I found it wordy and boring. One of the problems with reading things when you're young is that you make mistakes like that.

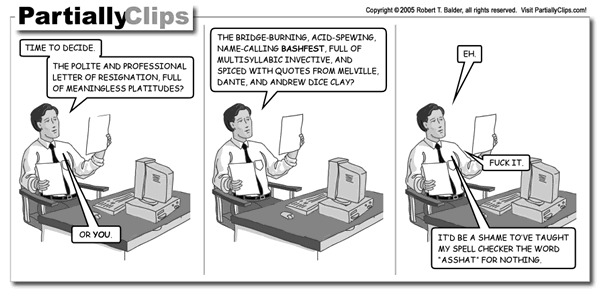

This morning over coffee I caught up with Rob Balder's PartiallyClips, and was tickled by the 8/11/2005 strip:

One of the best things about Rob's work is the density of ideas in it. This strip evokes the sunk-cost fallacy, the dilemma sometimes posed by the social and personal costs of truth-telling, and the curious puzzle of the word asshat, which is not in the Oxford English Dictionary despite having 516,000 Google hits. You might expect that I'm about to lead you on a scholarly tour of that word's social and linguistic history, but I won't, except to observe that this version of the history is not true, though it's funny. Instead, I'm going to quote from All the King's Men, where the appeal and the peril of truth-telling are evoked in a wordier but more serious way.

The novel is about Willie Stark, said to be a fictionalized version of Huey Long. At the point where we pick up the narrative, Stark is an idealistic rural lawyer who's been manipulated into running for governor by some politicians who want to split their opponent's rural vote. The story is told by Jack Burden, who has walked away from his PhD dissertation in history to become a journalist. Stark's campaign is not going well, because he bores his audiences with laundry lists of policy-wonk prescriptions. He's telling Burden about his ideas in a hotel-room interview:

He must have noticed that I wasn't giving a damn. He shut up all of a sudden. He got up and walked across the floor and back, his head thrust forward and the forelock falling over his brow. He stopped in front of me. "Those things need doing, don't they?" he demanded.

"Sure," I said, and it was no lie.

"But they won't listen to it," he said. "God damn those bastards," he said, "they come out to hear a speaking then they won't listen to you. Not a word. They don't care. God damn 'em. They deserve to grabble in the dirt and get nothing for it but a dry gut-rumble. They won't listen."

"No," I agreed, "they won't."

"And I won't be Governor," he said, shortly. "And they'll deserve what they get." And added, "The bastards."

After some more back-and-forth:

"What are you going to do?" I asked.

"I got to think," he replied. "I don't know and I got to think. The bastards," he said, "if I could just make 'em listen."

Sadie Burke is a political operative assigned to look after Stark:

It was just at that time Sadie came in. Or rather, she knocked at the door, and I yelled, and she came in.

"Hello," she said, gave a quick look at the scene, and started toward us. Her eye was on the bottle of red-eye on my table. "How about some refreshment?" she said.

"All right," I replied, but apparently I didn't get the right amount of joviality into my tone. Or maybe she could tell something had been going on from the way the air smelled, and if anybody could do that it would be Sadie.

Anyway, she stopped in the middle of the floor and said, "What's up?"

I didn't answer right away, and she came across to the writing table, moving quick and nervous, the way she always did, inside of a shapeless shoddy-blue summer suit that she must have got by walking into a secondhand store and shutting her eyes and pointing and saying "I'll take that."

She reached down and took a cigarette out of my pack lying there and tapped it on the back of her knuckles and turned her hot lamps on me.

"Nothing," I said, "except that Willie here is saying how he's not going to be Governor."

She had the match lighted by the time I got the words out, but it never got to the cigarette. It stopped in mid-air.

"So you told him," she said, looking at me.

"The hell I did," I said. "I never tell anybody anything. I just listen."

She snapped the match out with a nasty snatch of her wrist and turned on Willie. "Who told you?" she demanded.

"Told me what?" Willie asked, looking up at her steady.

And Sadie realizes that she faces a dangerous choice, which the narrator explains in terms of communicative interaction viewed metaphorically as a brawl:

She saw that she had made her mistake. And it was not the kind of mistake for Sadie Burke to make. She made her way in the world up from the shack in the mud flat by always finding out what you knew and never letting you know what she knew. Her style was not to lead with the chin but with a neat length of lead pipe after you had stepped off balance. But she had led with the chin this time.

As usual, maybe the mistake is not entirely a mistake.

... floating around in the deep dark the idea of Willie and the the idea of the thing Willie didn't know, like two bits of drift sucked down in an eddy to the bottom of the river to revolve slowly and blindly there in the dark. But there, all the time.

So, out of an assumption she had made, without knowing it, or a wish or a fear she didn't know she had, she led with her chin. And standing there, rolling that unlighted cigarette in her strong fingers, she knew it. The nickel was in the slot, and looking at Willie you could see the wheels and the cogs and the cherries and the lemons begin to spin inside the machine.

Now Sadie pushes the interaction along for a while by doing nothing:

"Told me what?" Willie said. Again.

"That you're not going to be Governor," she said," with a dash of easy levity, but she flashed me a look, the only S O S, I suppose, Sadie Burke ever sent out to anybody.

But it was her fudge and I let her cook it.

Willie kept on looking at her, waiting while she turned to the one side and uncorked my bottle and poured herself out a steady-er. She took it, and without any ladylike cough.

"Told me what?" Willie said.

She didn't answer. She just looked at him.

And looking right back at her, he said, in a voice like death and taxes, "Told me what?"

And then she gets to choose which letter to send, so to speak. Like Rob's middle manager, she decides for the one with the insults and the vulgarities and the literary allusions and the burning of bridges:

"God damn you!" she blazed at him then, and the glass rattled on the tray as she set it down without looking. "You God-damned sap!"

"All right," Willie said in the same voice, boring in like a boxer when the other fellow begins to swing wild. "What was it?"

"All right," she said, "all right, you sap, you've been framed!"

He looked at her steady for thirty seconds, and there wasn't a sound but the sound of his breathing. I was listening to it.

"Then he said, "Framed?"

"And how!" Sadie said, and leaned toward him with what seemed to be a vindictive and triumphant intensity glittering in ther eyes and ringing in her voice. "Oh, you decoy, you wooden-headed decoy, you let 'em! Oh, yeah, you let 'em, because you thought you were the little white lamb of God --" and she paused to give him a couple of pitiful derisive baa's, twisting her mouth -- "yeah, you thought you were the lamb of God, all right, but you know what you are?"

She waited as though for an answer, but he kept staring at her without a word.

"Well, you're the goat," she said. "you are the sacrificial goat. You are the ram in the bushes. You are a sap. For you let 'em. You didn't even get anything out of it. They'd have paid you to take the rap, but they didn't have to pay a sap like you. Oh, no, you were so full of yourself and hot air and how you are Jesus Christ, that all you wanted was a chance to stand on your hind legs and make a speech. My friends --" she twisted her mouth in a nasty, simpering mimicry -- "my friends, what this state needs is a good five-cent cigar. Oh, my God!" And she laughed with a kind of wild, artificial laugh, suddenly cut short.

Well, she goes on in that vein for some time.

Willie, previously a teetotaler, then drinks himself into a coma, and the next day, still drunk, gives a speech at a political BBQ that does indeed make 'em listen. He withdraws from the race, and begins the personal and political transformation that leads him later to the governorship as an unscrupulous populist demagogue.

So Sadie's speech was a sort of resignation letter -- it betrayed the political machine she worked for, and she pays for it when Willie makes her revelation public in his drunken oration the next day:

"Those fellows in the striped pants saw the hick and they took him in. They said how MacMurfee was a limber-back and a dead-head and how Joe Harrison was the tool of the city machine, and how they wanted that hick to step in and try to give some honest government. They told him that. But -- " Willie stopped, and lifted his right hand clutching the manuscript to high heaven -- "do you know who they were? They were Joe Harrison's hired hands and lickspittles and they wanted to get a hick to run to split MacMurfee's hick vote. Did I guess this? I did not. No, for I heard their sweet talk. And I wouldn't know the truth this minute if that woman right there --" and the pointed down at Sadie --- "if that woman right there --"

I nudged Sadie and said, "Sister, you are out of a job."

"-- if that fine woman right there hadn't been honest enough and decent enough to tell the foul truth which stinks in the nostrils of the Most High!"

But Sadie's speech was also a sort of letter of application, since it signed her up as the political architect of Willie's career.

It doesn't turn out well, for her or for anyone else. But like they say, read the whole thing.

Posted by Mark Liberman at September 12, 2005 09:24 AM