November 06, 2005

Young men talk like old women

Well, in a couple of specific respects, anyway. Details follow...

Over the past few years, the Linguistic Data Consortium (LDC) has collected and transcribed a large number of telephone conversations for the purpose of speech recognition research. Some of this has already been published (sample catalog entries are here and here), and the rest will be published soon. The collection is an interesting basis for some new sorts of linguistic research, in my opinion, and below I present a small example of a suggestive result -- about the interaction of age, sex and fluency -- that took me about half an hour to produce.

First, let me try to explain why I think collections like this one represent a new research opportunity. One new thing is simply the fact of access to an existing corpus: because the audio and transcripts are already done, and some demographic data is available about the speakers, it's easy to ask and answer many simple questions that wouldn't motivate the time, effort and funding needed to create a special-purpose data collection. Another new thing is the scale of this particular collection: combining various publications into a single database, we have 28,000 conversational sides (and therefore about 14,000 conversations) whose transcripts comprise more than 26 millions words, involving about 12,000 speakers from all over the U.S. (with some Canadians and a few speakers of other kinds of English). Finally, the fact that the material is published means that research results can easily be checked, replicated (or challenged) and extended by others.

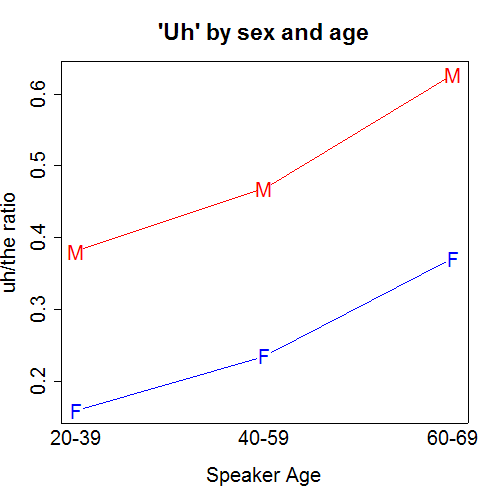

OK, here's my little result. I took a quick look at demographic variation in the frequency of the filled pauses conventionally written as "uh" and "um". For technical reasons that I won't go into here, I used the frequency of the definite article "the" as the basis for comparison. Thus I selected a group of speakers (e.g. men aged 60-69), counted how often they were transcribed as saying "uh", and to normalize that count (since the number of people in each category was different) I divided by the number of times the same speakers were transcribed as saying "the".

If we take the relative frequency of "uh" as a measure of disfluency, then the graph above shows that

- disfluency (or at least uh-usage) increases with age;

- at a given age, men are more disfluent than women (or at least they use uh more than women).

As a result, men 20-39 have roughly the same uh/the ratio as women 60-69.

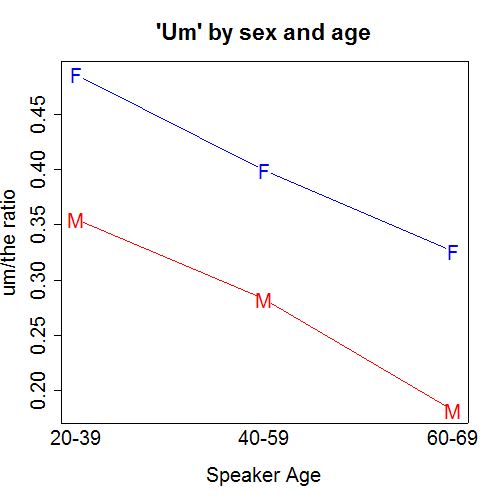

The facts for "um" are quite different:

The graph above shows that

- the frequency of "um" decreases with age;

- at a given age, women use "um" more than men.

Again, the rate of "um" usage for the younger men is almost the same as the rate of "um" usage for the older women.

It's not entirely suprising that "uh" and "um" pattern differently. For some background, read this 1/5/2004 post on statistical language modeling of filled pauses, which also references an excellent1/3/2004 NYT article by Michael Erard entitled "Just Like, Er, Words, Not, Um, Throwaways". Erard cites a 2001 Language and Speech article by Heather Bortfeld which he describes as finding that "Men say uh and um more than women, though their overall disfluency rate was the same." I'm not sure why Bortfeld's results on um are different from what I found -- more on this later.

[Update: the paper is Bortfeld H.; Leon S. D.; Bloom J. E.; Schober M. F.; Brennan S. E., "Disfluency Rates in Conversation: Effects of Age, Relationship, Topic, Role, and Gender", Language and Speech, 2001, 44(2), 123-147. There is no disagreement after all -- the Bortfeld et al. paper just aggregated all "fillers", including both uh and um, as a single count. Since the effects of age and on uh and um are apparently opposite, this may have blurred the results. One reason for this approach might have been that their total corpus size was about 192,000 words, and the counts of fillers for some of the demographic categories may have been fairly small.]

The paper featured in Erard's article is Herbert H. Clark and Jean E. Fox Tree, "Using uh and um in spontaneous speaking", Cognition 84 (202) 73-111. Their notion is that "speakers use uh and um to announce that they are initiating what they expect to be a minor (uh), or major (um), delay in speaking. ... The evidence shows that speakers monitor their speech plans for upcoming delays worthy of comment. When they discover such a delay, they formulate where and how to suspend speaking, which item to produce (uh or um), whether to attach it as a clitic onto the previous word (as in “and-uh”), and whether to prolong it. The argument is that uh and um are conventional English words, and speakers plan for, formulate, and produce them just as they would any word."

The general idea is a persuasive one, but it doesn't explain the striking (apparent) effects of age and sex.

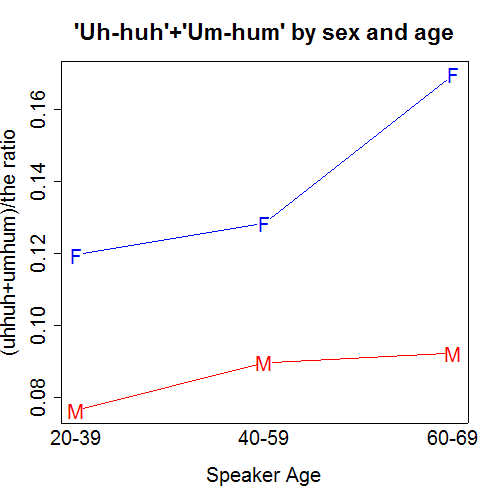

One last plot deals with the frequency of the assenting murmurs conventionally transcribed as "uh huh", "um hum" or "mm hmm". I needed to make these measurements in order to subtract "uh huh" counts from the counts for "uh", and "um hum" counts from the counts for "um". Indeed, in interpreting all of these graphs you should be concerned about the possibility that some other transcriptional or demographic issue is NOT being controlled for. The evidence should be regarded as provisional until I (or someone else) has the time to examine the demographics more carefully, and check a large enough sample of the original audio -- but the nice thing about published corpora is that these are straightforward if tedious tasks!

This graph shows that

- the frequency of assenting murmurs increases with age;

- at a given age, women use assenting murmurs more than men.

I guess that these results are more or less consonant with the current conventional wisdom about language and gender, which is probably a good reason to distrust them. And there are a half a dozen obvious caveats, which I'll discuss another time. Still...

A bit more about the data I used:

The overall collection paradigm was pioneered by the Switchboard project, carried out at Texas Instruments in 1990-91. Other conversations were collected at LDC between 1999 and 2004. Calls were bridged digitally through a "robot operator", which recorded them as well as keeping track of the participants (by assigned PIN and by phone number). Participants were paid to take part in one or more conversations on specified topics with randomly-selected partners. Participants could indicate interest in available topics when they enrolled, and could opt out at call time if they didn't want to discuss a given topic. There were more than 100 topics, involving short instructions like "Discuss recent social changes. How is life in America different today compared to living ten, twenty, or thirty years ago?" or "Do you believe that the US government should provide universal health insurance, or should at least make it a long term goal? How far in that direction whould you be willing to go? What do you see as the most important pros and cons of such a program?" or "The topic is clothing. Please find out how the other caller typically dresses for work. How much variation is there from day to day? How much variation is there from season to season?".

The transcripts were produced in several different ways, but the largest number were done by a professional transcription service, to specifications intended to make the results as consistent as possible across the collection. In that portion of the data, the transcribers were encouraged to work quickly rather than to be absolutely accurate in disfluent regions, and so the filled pauses were probably somewhat undercounted.

The collection that I used can be searched at LDC Online, including the ability to read individual transcripts and listen to the associated audio. The full collection is available to LDC members, but anyone can get a guest account to search the "Switchboard" part of the corpus, comprising about 5000 conversational sides.

[Update: more here.]

Posted by Mark Liberman at November 6, 2005 08:35 AM