January 03, 2006

What would Whorf say?

Something about most anything, it seems. I've recently come across two papers about the influence of language on thought and action. Both papers strike me as suggestive (in roughly the same way) and also not entirely convincing (in roughly the same way). Otherwise, the two papers are just about as different as they could possibly be.

The first paper is Heesook Kim, "What would Sapir and Whorf talk about the social conflicts in the South Korean Society" [sic], in 어너학 [Eoneohag -- Journal of the Linguistic Society of Korea], No. 40, December 2004. Actually, it's just the translated title and abstract of a paper published in Korean, which I haven't read. (The English is somewhat imperfect, though infinitely better than my Korean.) Here's the abstract:

Like Taiwan, South Korea is a somewhat lately democratized society. However, comparing two countries, South Korea has been featured with more social conflicts, we find. In modern times, both have shared a similar experience in social, political and economic aspect. They have been neighbors even geographically. Then, how could one society reveal more confrontations among the members than the other? With the help of Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, we tried to show that honorifics in Korean, which is believed the most complex in the world, is reponsible for the distinction. We proved that honorifics, which was born and developed in the pre-modern social structure, tends to prevent equality, which is necessary for people to face one another on equal footing, from being established among the individuals and make people seek collective actions to make their voices heard and resolve difference in their interests in equal terms.

The idea, I guess, is that if your language forces you to use honorifics all the time, drawing your attention to your place in society relative to others, you will be more conscious of distinctions in social status; and therefore you will be more likely to interpret issues in terms of social status, and/or to feel a greater sense of solidarity with your social peers. That makes some sense.

But if the facts about social conflict had been different -- more recent conflict in Taiwan than in Korea -- you might have taken Whorf the other way. Maybe the use of honorifics helps keep people grounded in their traditional roles, and less likely to challenge the traditional division of power. And in fact, if we take a slightly larger geographical and historical frame, it's not obvious to me that China/Taiwan has had less social conflict than Korea.

Any way you slice it, it seems to me that it's hard to make a strong case based on two data points. If you had a survey of 10 or 20 dominant national languages, convincingly quantifying the degree to which they reflect the relative social status of conversational participants; and an independent survey of the degree of social conflict in the countries in which these languages are spoken; and a clear correlation between the two measures...

(My evaluation of this paper is obviously limited by the fact that I've only read the abstract -- perhaps the body of the paper presents other arguments or addresses these points in some way.)

The second paper is Aubrey L. Gilbert, Terry Regier, Paul Kay, and Richard B. Ivry, "Whorf hypothesis is supported in the right visual field but not the left", PNAS, vol. 103, 489-494, January 10, 2006. Here's the abstract:

The question of whether language affects perception has been debated largely on the basis of cross-language data, without considering the functional organization of the brain. The nature of this neural organization predicts that, if language affects perception, it should do so more in the right visual field than in the left visual field, an idea unexamined in the debate. Here, we find support for this proposal in lateralized color discrimination tasks. Reaction times to targets in the right visual field were faster when the target and distractor colors had different names; in contrast, reaction times to targets in the left visual field were not affected by the names of the target and distractor colors. Moreover, this pattern was disrupted when participants performed a secondary task that engaged verbal working memory but not a task making comparable demands on spatial working memory. It appears that people view the right (but not the left) half of their visual world through the lens of their native language, providing an unexpected resolution to the language-and-thought debate.

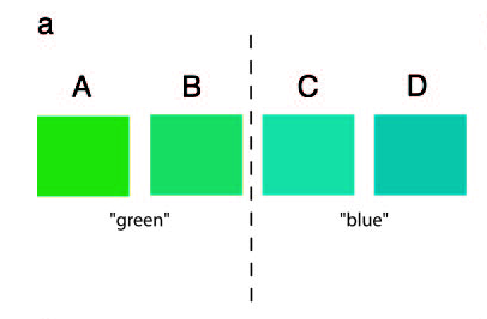

There were 13 subjects, all Berkeley students. The stimuli were made up of colored squares drawn from a set of four, spanning a series from "green" to "blue":

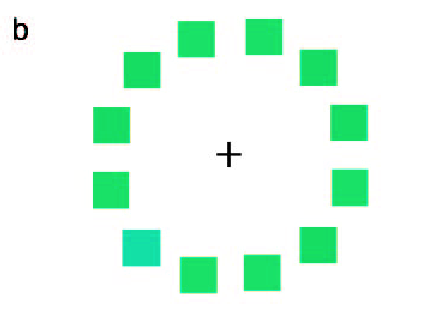

On each trial, the subject was shown a ring of 12 squares surrounding the fixation point. Eleven of the twelve square were the same color, and one (in a random location) was a different color.

The subject's task was to indicate as rapidly as possible whether the different-colored square was in the left half or the right half of the array. The oddball square could be could be of the "same" basic color-name category (in English!) or of a different category.

The crucial thing about the experimental design is that the left side of the visual field projects to the right (non-dominant) side of the cerebral cortex, while the right side projects to the left (language-dominant) side of the cortex.

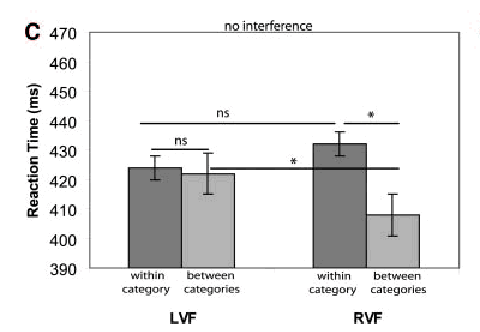

And here's some of the results:

In the "no interference" condition, the subjects were significantly faster when making a between-color-category judgments (i.e. the oddball was green and rest were blue, or vice versa) in the right visual field. (Eyeballing the figure, the difference was apparently only about 15-30 msec. out of about 420 msec., or about 5% -- but that's what reaction time experiments are usually like.)

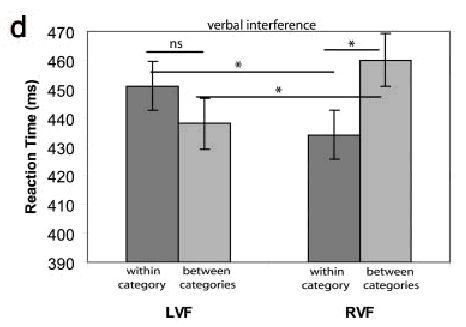

When subjects were distracted by having to silently rehearse an 8-digit number during a block of trials (and they had to recall it at the end of the block), the results were quite different:

In this case, all the reaction times were a bit longer, of course. But now in the right visual field, the within-category trials were significantly faster than the across-category trials! The effect of (English) color category was reversed. In fact, curiously, the RVF within-category trials were now also significantly faster than the LVF within-category trials, while the LVF between-category trials were faster than the RVF between-category trials.

In a second experiment, the authors compared a different verbal-interference task (remembering an irrelevant color word, like "red") with a non-verbal interference task (remembering the arrangement of a spatial grid of square). They found that with the non-verbal interference, RVF between-category judgments were faster (similar to the no-interference condition), while with the verbal interference, RVF within-category judgments were again faster -- and again, the same curious inversion of effects obtained in the verbal interference case, with the RVF within-category trials being significantly faster than the LVF within-category trials, while the LVF between-category trials were faster than the RVF between-category trials.

Well, you can read the details for yourself, if you want. It's a great piece of work, and the authors' interpretation makes a lot of sense, and might well be true. But a couple of things about it worry me.

One is that the explanation might have worked just as well if the experiment had come out quite a bit differently. For example, if the LVF between-category reaction times had been slower instead of faster, you could say that it's because the color names are interfering with a faster non-linguistic process. Indeed, you have to say something like that to explain the (unpredicted) result that the verbal interference task actually reverses the effect, making between-category reaction times significantly slower than within-category reaction times.

Other possible results -- basically anything except a situation in which color category makes no difference, or doesn't interact with visual field -- could similarly be given a Whorfian interpretation.

A second cause of worry is that the experiments, though extensive, are somewhat limited. There are just four colors, and one basic color category distinction. The particular colors used have lots of other properties besides their relationship to English color-name boundaries. It would be unfortunate (for example) to learn that things are quite different if we use purple-to-red instead of green-to-blue, or if we use a green-to-blue sequence with different saturation or brightness.

We might also wonder what happens with subjects who have various other sorts of cerebral lateralization, for language and perhaps other knowledge and skills. Or what happens if you ask subjects to judge whether the oddball square is in the top half or the bottom half of the array, instead of left vs. right.

And finally, the cross-linguistic shoe hasn't dropped yet. The authors observe that "a majority of the world's languages" use a single word for the basic color categories of the green-to-blue sequence they used in this experiment. So the prediction is that the speakers of these languages will not show any effect of the boundary between stimuli B and C; and similarly for other such boundaries on other color sequences.

A crucial difference between the paper on honorifics and the paper on colors is that it's a straightforward job of work to do more color experiments of the same general sort, and no doubt we'll see some along these lines in the future. Furthermore, the same LVF-vs.-RVF RT paradigm could be used with things other than color, e.g. a range of similarly shaped unnamable pictures vs. pictures with a range of similar-sounding names vs. pictures with a range of semantic similarities. A whole psycholinguistic industry devoted to seeking Whorfian effects in cortical RT asymmetries may be ahead of us.

[More Language Log posts referencing Benjamin Lee Whorf are here. There are shockingly many of them.]

Posted by Mark Liberman at January 3, 2006 07:44 PM