July 26, 2006

The moan of the dunes

Who you gonna believe, the NYT science section or your own lyin' ears? Reporting on some very interesting work by Stéphane Douady and others on the physics of "singing sands", Kenneth Chang ( "Secrets of the Singing Sand Dunes", July 25, 2006) can't resist a musical lede:

Who you gonna believe, the NYT science section or your own lyin' ears? Reporting on some very interesting work by Stéphane Douady and others on the physics of "singing sands", Kenneth Chang ( "Secrets of the Singing Sand Dunes", July 25, 2006) can't resist a musical lede:

The dunes at Sand Mountain in Nevada sing a note of low C, two octaves below middle C. In the desert of Mar de Dunas in Chile, the dunes sing slightly higher, an F, while the sands of Ghord Lahmar in Morocco are higher yet, a G sharp.

Unfortunately for Chang's credibility, he (or more likely one of his editors) chose to accompany the article by a lovely video clip (identified as being "sounds .. 'played' on a singing dune located in the Atacama Desert in Chile") providing singing-sand sounds that are more like moans than sung notes, each sound clearly spanning a fairly wide range of pitches.

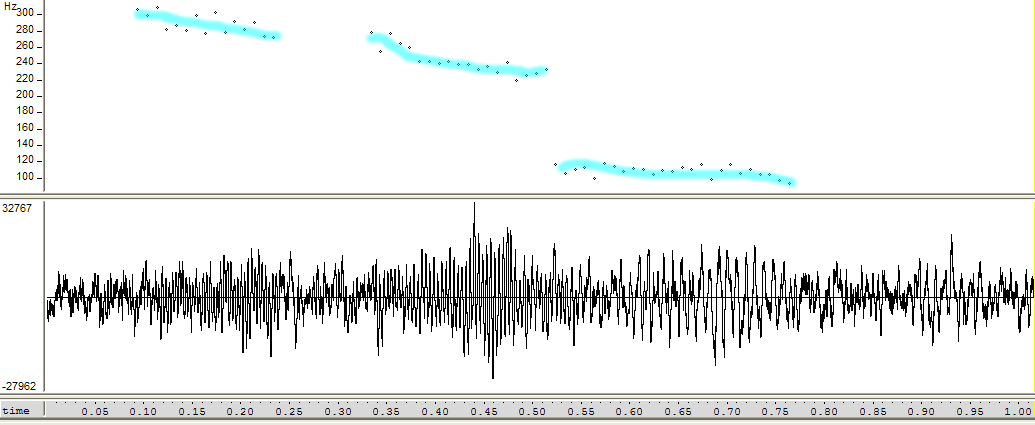

Here's a graphical representation of one example [audio clip], with an automatically-generated pitch track on which I've manually sketched some trend lines for clarity:

This particular sound sequence, produced by one sweep of the dune-player's hand, has an initial segment that falls from about 308 Hz (a bit below the D# just above middle C) to about 226 Hz (half-way between A and A# below middle C), followed by a period-doubling (i.e. pitch halving) and a somewhat more level-pitched segment ending around 103 Hz (just below G#, in terms of musical pitch-classes relative to A=440).

In other words, this moan of the dunes starts just above middle C, falls by a tritone (six semitones), and then drops by an octave to end about an octave and a fifth lower.

Even if you have perfect pitch (and I certainly don't), you probably can't hear the intervals involved accurately, since people with perfect pitch don't perceive the pitch of such glissandi very clearly -- or at least that's what a couple of them have told me. However, anybody with normal hearing and pitch perception can tell by listening to this clip that the dune's sound, in this case, is not well characterized as a "note", but rather is a falling glissando spanning a considerable range.

This is a small nit to pick, in an interesting and well-written article about a nice piece of research. I've posted about it not because I like to play "gotcha" with journalists -- in fact I don't enjoy it at all -- but because this is such a clear example of such a common problem. More often than not, the popular presentations of scientific or technological results are strikingly at variance with features of the results themselves, features that are obvious to anyone who knows anything about the subject or who looks at the primary sources with a bit of common sense. Sometimes this is entirely the fault of the scientists and engineers, and their PR representatives often contribute as well, but in the end, the largest share of guilt belongs to the reporter and editor, whether they juice up the story themselves or credulously accept the juice from another source. And in this internet age, it's increasingly easy for readers to check things out, and to blog what they find.

There's not a lot of extra "juice" in this case -- just Chang's choice to lead with a comparison of deserts as if they were organ pipes. We're not talking about a flat-out fabrication, like the stuff about how email lowers IQ more than pot and men are emotional children, or a preposterous exaggeration, like the idea that Germans are grumpy because of umlauts. In this case, it's just an attempt to grap the reader's interest with the cute idea that deserts have characteristic pitches, before getting to the physics part. And Chang's lede is not totally invented, anyhow, since Douady's article suggests that the pitch of the dune sounds depends on the statistics of grain sizes (which may be different for different deserts), and offers some lab results citing different pitches for sand samples from different locations. However, the video clip accompanying the article makes it clear that at least some of the dune sounds, in their natural state, are not stable pitches at all. So Chang's lead, though attractive, is directly contradicted by the evidence in his sidebar video.

Well, actually, Chang compounds the problem when he tries to explain, later in the opening paragraph, that

While the songs are steady in frequency, the dunes do not have perfect pitch. At Sand Mountain, for example, dunes can sing slightly different notes at different times, from B to C sharp. [emphasis added]

Um, Kenneth, your own video sidebar makes it clear that the "songs" are NOT necessarily "steady in frequency". Isn't that a little embarrassing?

[The scientific paper is S. Douady, A. Manning, P. Hersen, H. Elbelrhiti, S. Protiere, A. Daerr, B. Kabbachi, "The song of the dunes as a self-synchronized instrument", unpublished ms. 12/2004, revised 1/2006, to appear in Physical Review Letters (?). More info about moaning dunes is available on Douady's web site.]

[There is no truth to the rumor this story is the oneiric source of the question famously asked by Dan Rather's assailant in 1986. It's for that reason that I resisted the temptation to title this post "What's the frequency, Kenneth?"]

[Update -- Kenneth Chang emailed:

Geez, if you're going to pose questions/insults, you really should provide some straightfoward way for someone to reply.

From the abstract of the paper: "Since Marco Polo (1) it has been known that some sand dunes have the peculiar ability of emitting a loud sound with a well defined frequency, sometimes for several minutes."

The notes are taken from Table 1, which I hope I didn't mess up.

The discrepancy arises, I believe (from reading the paper), because you can generate different notes by changing the speed you push the sand, like in the video (and Table 2). There are also overtones. In naturally occurring avalanches, there is one characteristic speed and hence one characteristic note.

So... we should have put a better explanation accompanying the Web video, It's unfortunately impossible to include all these nuances in a 300-word article.

It's absolutely true that the abstract of the Douady et al. paper suggests that the pitches are typically level, and that the information about the particular association between deserts and pitches comes from Table 1 in the Douady et al. paper:

This is what I meant by alluding in a general way to the source of the idea in the cited paper, but I should have been more precise. I could quibble a tiny bit with Chang's translation from Hz to musical pitch-classes, but what's a semi-tone or so among friends? And the plain fact is that the implication of a fixed connection with between deserts and pitches via characteristic sand-grain sizes is suggested by this part of the paper that Chang is reporting on. It's also very plausible that naturally-occurring avalanches usually involve stable velocities and therefore stable pitches.

On this basis, I owe Chang an apology for any implication that he was responsible for the idea of deserts being musically tuned: it comes pretty directly from the Douady paper.

The figure that helps explain why the sounds in the video clip are not steady pitches is reproduced below:

This (their Figure 2) shows "Frequency emitted by pushed (sheared) sand, measured in laboratory experiment, as a function of two laboratory control parameters, height of mass of sand, H, and velocity of pushing blade, V." See the paper for further details -- but the figure clearly shows the same sand, from the same desert, emitting a range of frequencies spanning more than three octaves. Presumably, as Chang suggests in his note, the velocity of the dune-player's hand in the video is standing in for the velocity of the blade, and the velocity contour of his gestures is produces a corresponding pitch contour.

So Douady and his co-authors are to arguably to blame for publishing a misleading Table 1, without a clear explanation of the fact that the implied close connection among deserts, grain sizes and (level) pitches is not generally true in the laboratory, and may be true in the field only under certain circumstances, and in particular isn't true in some of their own field examples. We can't blame Kenneth Chang (who is clearly an excellent science writer in general, and to be commended for bringing an interesting piece of work to general attention) for anything worse than a minor failure to read (and listen) critically -- and it's plausible in fact that he understood the whole situation from the beginning, but simply couldn't fit the whole discussion within the rigid article-length limit that he had to work with.

I'm glad I'm a blogger! It's a lot easier to write more than to write less. ]

Posted by Mark Liberman at July 26, 2006 08:43 AM