January 30, 2007

People in Glass Houses

I'm always amazed when people try to make political points based not on events or people's explicit statements but on subtle inferences that they are unequipped to make. The most recent example to catch my eye is this post by Robert Spencer at Jihadwatch, a blog to which I referred the other day.

Spencer quotes the following passage from an AP news item:

Benkahla was one of only two defendants who were acquitted in the government's prosecution of a dozen Muslim men who participated in what the government called a "jihad network" that used paintball games in the Virginia woods in 2000 and 2001 as a means to train for holy war around the globe.

IHe criticizes the Associated Press for questioning the truth of the government's allegation that the men were training for jihad:

The government called it a "jihad network." That's AP for you. That they gained ten convictions on that basis might suggest that there was something accurate in this designation, but you wouldn't get that impression from this story.

Spencer seems to think that putting "jihad network" in quotes calls it into question. He's wrong. There are a number of reasons for putting a phrase into quotes. Doubt about the validity of the characterization is one of them, but it is by no means the only one, or even the most common or default. Another reason is that the phrase is someone else's and is not a standard term. That's almost certainly what the AP intended here.

What is especially strange here is that although the quoted phrase itself admits of ambiguity as to the AP's intended meaning, the passage as a whole does not. The relative clause "who participated in what the government called a 'jihad network' that used paintball games in the Virginia woods in 2000 and 2001 as a means to train for holy war around the globe." is factive, that is, it is a clause that may only be felicitously uttered if the speaker believes the proposition it expresses to be true. The AP article therefore asserts as true the proposition that the men trained for holy war, which refutes Spencer's claim that the AP is casting doubt on the government's position.

[Comment by Mark Liberman:

There's an ambiguity here that Bill may have missed.

When the AP wrote

Benkahla was one of only two defendants who were acquitted in the government's prosecution of a dozen Muslim men who participated in what the government called a "jihad network" that used paintball games in the Virginia woods in 2000 and 2001 as a means to train for holy war around the globe.

did they mean for everything after called to be part of its complement, and thus explicitly flagged as merely as a government allegation? This would be an odd editorial choice, as Spencer says, since it suggests that the whole holy-war training activity might be a figment of the prosecutors' imagination, despite the convictions obtained in a number of other cases.

Or did they intend the complement of called to end after "jihad network", so that the rest of the sentence is in the AP's own voice? That would be more in line with (what I take to be) the normal journalistic practice.

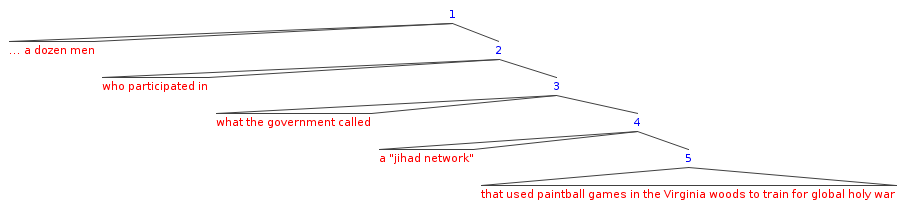

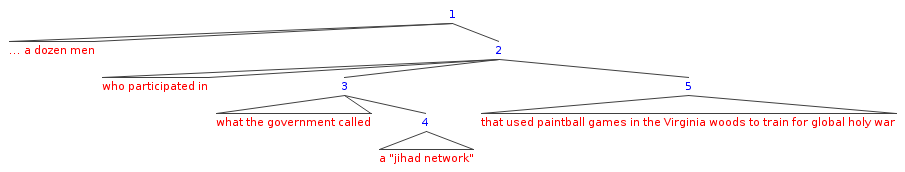

Simplifying the sentence and drawing only the relevant structure, this is the difference between

and

Bill is relying on the second interpretation, I guess, but it seems to me that the first interpretation is the more natural one.

Also, the use of the term "factive" in this context may be confusing.

There's a 35-year-old neologism, due to Paul and Carol Kiparsky and widely adopted by linguists, that uses "factive" to describe verbs like know, regret, learn etc., which presuppose the truth of their complements, in contrast to verbs like believe, complain, hear, etc., which do not. This distinction came up in a couple of earlier LL posts ("Verb semantics and justifying war", 9/21/2003; "Bush's understanding of factive verbs", 9/23/2003). But there's no factive verb in the AP sentence under discussion. ]

[Response to Mark's comments:

With regard to "factive", I'm well aware that there is no factive verb here. That's why I talked about the clause being factive, not the verb. I don't agree that "factive" always suggests the use of a factive verb. Kiparsky and Kiparsky's "Fact" paper, while indeed a classic, and one whose authors are both good friends of mine, does not define the admissible uses of "factive".

As for the putative structural ambiguity, I don't think that it is really there. Not only do I consider the interpretation that I relied on, the second one, to be more natural, the first one, in which the relative clause is part of the complement of "call", is impossible as written. To get that interpretation the relative clause would have to be within the quotes, which it is not.

It is also important to note that even if one does get both readings of the relative clause, all that does for Spencer is to make his interpretation possible. His criticism is only valid if the interpretation on which the AP is doubting what happened is the only one. So even if Mark is right about the ambiguity, Spencer's criticism of the AP is unwarranted.]

Posted by Bill Poser at January 30, 2007 03:51 AM