February 02, 2007

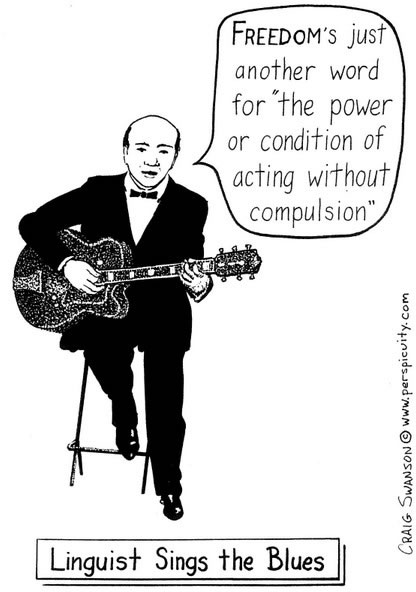

Linguist sings the blues

A cartoon from Craig Swanson's Perspicuity notebooks:

[Hat tip: Lance Nathan]

Here's part of Swanson's explanation:

I remember years ago getting quite excited when I heard that Elton John also loved words. I was half listening to the radio when I heard him sing "... and I guess that's why they call it the blues." Cool! I had often wondered how the blues got its name.

Sure, the color blue evokes emotion, but is this merely a result of cultural conditioning? Or is it something that is innate? And even if it is in us, wouldn't someone still have been the first to have observed it? Now, thanks to Mr. John these questions would finally have an answer. All I had to do was wait to hear the song again.

"Time on my hands could be time spent with you" Huh? "Laughing like children, living like lovers" What the...? "Rolling like thunder under the covers" Hey! This isn't the etymology of the word blues. "And I guess that's why they call it the blues." Why this is a stupid love song!

And at that fateful moment in 1984, I made a promise to myself: From that day forward I would never again look to popular culture for word origins.

OK, but I need to point out that in 2005, here on Language Log, we indulged in a small exchange about the phrasal template "that's why they call it X" (starting from Eric Bakovic's "That's why they call it X", 6/3/2005), without discussing the connection to this song (though of course we did notice that one of the possible values of X is "the blues"). The lyrics are attributed to Bernie Taupin, by the way.

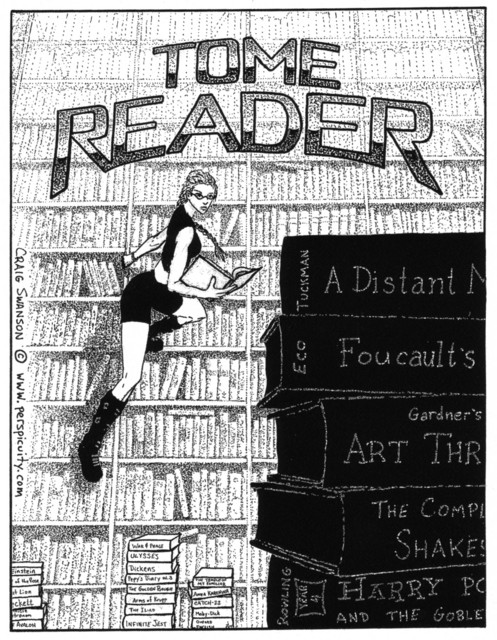

Another Craig Swanson mind/body kind of joke:

This one graphically substitutes the environment rather than the person. And turn about is fair play, since Tomb Raider takes off from the Indiana Jones movies, whose main character is a fictionalized anthropologist with some tome-reading chops of his own.

[Update -- John Cowan elaborates the point:

The wikipedia entry lists a number of possible sources, analogues, and influences; in addition to the usual suspects like Roy Chapman Andrews and Percy Harrison Fawcett, the last-named person is our very own Sir William "India" Jones: "sprung from a common source" and all that. It isn't too inappropriate: Indiana, it seems, actually studied philology at the Sorbonne in the early 1920s. It would be interesting to figure out who his professors were.

Almost any anthropologist of Indiana's generation would certainly have been a linguist as well. As for his philology professors at the Sorbonne in the 1920s, they would certainly have included Antoine Meillet; and one of his fellow students would have been Millman Parry, at least if he had stayed through 1924. ]

Turning back to freedom, it seems to me that it's really the philosophers who deserve to be tagged as offering solemn but unattractive alternatives to the Kristofferson/Foster definition of freedom. Thus Engels in Anti-Dühring:

Hegel was the first to state correctly the relation between freedom and necessity. To him, freedom is the insight into necessity (die Einsicht in die Notwendigheit).

"Necessity is blind only in so far as it is not understood [begriffen]."

Freedom does not consist in any dreamt-of independence from natural laws, but in the knowledge of these laws, and in the possibility this gives of systematically making them work towards definite ends. This holds good in relation both to the laws of external nature and to those which govern the bodily and mental existence of men themselves — two classes of laws which we can separate from each other at most only in thought but not in reality. Freedom of the will therefore means nothing but the capacity to make decisions with knowledge of the subject. Therefore the freer a man's judgment is in relation to a definite question, the greater is the necessity with which the content of this judgment will be determined; while the uncertainty, founded on ignorance, which seems to make an arbitrary choice among many different and conflicting possible decisions, shows precisely by this that it is not free, that it is controlled by the very object it should itself control.

"Freedom is die Einsicht in die Notwendigheit" is a hard line to set to music; but are there any philosophical slogans that have justified more crimes than this one?

In any case, Hegel was surely not the first to have the paradoxical thought that more freedom means less choice. Thus the Order for Morning Prayer of the 1662 Episcopal Book of Common Prayer:

O GOD, who art the author of peace and lover of concord, in knowledge of whom standeth our eternal life, whose service is perfect freedom; Defend us thy humble servants in all assaults of our enemies...

Or going back to the Dhammapada:

I do not call him a brahmin who is so by natural birth from his mother. He is just a supercilious person if he still has possessions of his own. He who owns nothing of his own, and is without attachment -- that is what I call a brahmin.

He who, having cut off all fetters, does not get himself upset, but is beyond bonds -- that liberated man is what I call a brahmin.

And we won't even mention Orwell's version of the paradox:

The Ministry of Truth -- Minitrue, in Newspeak -- was startlingly different from any other object in sight. It was an enormous pyramidal structure of glittering white concrete, soaring up, terrace after terrace, 300 metres into the air. From where Winston stood it was just possible to read, picked out on its white face in elegant lettering, the three slogans of the Party:

WAR IS PEACE

FREEDOM IS SLAVERY

IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH

I prefer the Kristofferson/Foster version. It's more ambiguous and it scans better:

Freedom's just another word for nothing left to lose. Nothing ain't worth nothing but it's free.

In comparison, all that we linguists really have to contribute to this discussion is the controversy over whether there is really ever any free variation (since all communicative choices have consequences)..

Posted by Mark Liberman at February 2, 2007 07:12 AM