March 14, 2007

Beware of sleeping idioms

As part of its "offbeat" news offerings, the Associated

Press reports on a cigarette ad campaign in Indonesia that has

angered the national police force, so much so that the manufacturer PT

Djarum now faces possible legal action. Here is how the AP describes

the offending ad, which has appeared on billboards, on television, and

in magazines:

As part of its "offbeat" news offerings, the Associated

Press reports on a cigarette ad campaign in Indonesia that has

angered the national police force, so much so that the manufacturer PT

Djarum now faces possible legal action. Here is how the AP describes

the offending ad, which has appeared on billboards, on television, and

in magazines:

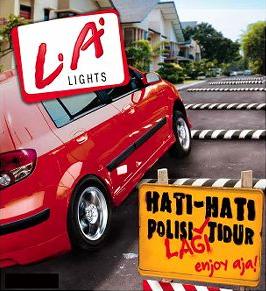

The ad is a visual and linguistic pun on the phrase "sleeping policemen," which in Indonesia is a term used for speed bumps. It features a road sign warning motorists of bumps, amended to read "Be careful, the police are snoozing."

Indonesian wordplay is one of my favorite topics, so I tracked down a copy of one of these ads on a local blog. It turns out the linguistic trick used in the ad campaign isn't so much a pun as it is the literalization of an old idiom that spans many languages.

The ad shows a car passing over a series of speed bumps, as they're known in US English. Speakers of British English more commonly refer to these artificial ridges as "road humps," or more colloquially "sleeping policemen." In Indonesian, the idiom "sleeping policeman" has been calqued into polisi tidur, as indicated by the caution sign depicted in the ad:

hati-hati polisi tidur (be) careful police sleep(ing) 'Beware of sleeping policemen.'

The grafittoed insertion between polisi and tidur is lagi, a progressive aspect marker. In Indonesian, tense and aspect are not marked on the verb but are rather indicated by free-standing lexical items in the predicate. Perfective aspect is marked by words like sudah or telah ('already'), while progressive aspect is marked by sedang, or more colloquially, lagi. Thus the interpolation of lagi transforms the idiomatic noun phrase polisi tidur into a phrase that must be interpreted as a full clause with tidur ('sleep, asleep') in the predicate: '(the) police officer is sleeping' or '(the) police are sleeping,' depending on whether polisi is construed as singular or plural:

hati-hati polisi lagi

tidur (be) careful police PROG

sleep(ing) 'Beware, the police are sleeping.'

The jaunty use of colloquial lagi to undercut the message of the caution sign is reinforced by the appended exhortation Enjoy aja! 'Just enjoy (it)!', where aja is a clipped form of saja ('just') common in urban centers like Jakarta, and enjoy is of course a loanword from English. This tag-line is used throughout PT Djarum's advertising for its L.A. Lights brand, a mild variety of the company's popular clove cigarettes. The ads are a transparent appeal to hip, young urbanites (or those who aspire to their ranks), the types who might pepper their speech with Jakarta-style colloquialisms and borrowings from (American) English. The advertisers are also trying to connect to their target demographic through the wordplay of polisi lagi tidur, which is a rather obvious joke about the laziness of law enforcement (on par with American jokes about cops and doughnuts), exploiting the humor already lying dormant in the old "sleeping policeman" idiom.

But even mild linguistic subversion is a potentially dangerous

practice in Indonesia, even after the fall of Soeharto's oppressive New

Order regime nearly a decade ago. The police remain one institution

that does not tolerate derision of any sort, under penalty of law. As

the AP article notes, members of a Balinese alternative rock band are

currently standing trial for performing a song with lyrics supposedly

comparing police to dogs. The case against the rockers relies on an

uncharitable reading of the line, Anjing! Kukira preman. Anjing!

Ternyata polisi. ('Dog! I thought it was a gangster. Dog! Turned

out it was a cop.') Anjing

'dog' is a derogatory insult in Indonesian, but it also can be used as

an interjection expressing annoyance or anger. The lyrics seem to use

the latter sense, but the prosecutor in the case says that "language

experts" have determined that the song contains "language insulting the

police force." (More details here.)

Back to the sleeping policemen. Before spreading to languages like

Indonesian via loan-translation, the "sleeping policeman" idiom seems

to have originated as a variation on an earlier expression, "silent

cop" or "silent policeman," used originally to refer to a structure

placed in the middle of an intersection to direct traffic. The

OED has a 1934 cite for "silent cop" from Australia and a 1965 cite for

"silent policeman" from New Zealand. But the newspaper databases

show US cites for "silent cop/policeman" as early as 1914, in cities

from Fitchburg, Massachusetts to Racine, Wisconsin:

Fitchburg (Mass.) Sentinel, July 14, 1914, p. 5

The sign works out satisfactorily when the traffic is not heavy, but when there is a rush at this busy corner four vehicles are sometimes circling the silent cop at the same time, and others are coming from all points of the compass.

Hartford (Conn.) Courant, July 26, 1915, p. 7

Danbury has a "silent cop." At least, that is what Danbury calls it, not recognizing the contradiction contained in the two words. The silent cop consists of a post about five feet high surmounted by a box on each side of which is painted the words "Keep to the Right" and bearing aloft a lantern.

Racine (Wisc.) Journal-News, Aug. 20, 1915, p. 12

Chief Baker stated at that time that he had purchased six silent policemen, in other words, signs to be placed at the intersection of busy street corners directing vehicles to turn to the left or right and that it would possibly stop, to a great extent, violation of the rules of the road.

By the late 1920s, "silent policemen" had evolved into the forerunners of automatic traffic lights, and variants could be found around the globe. (In Australia, the "silent cop" was evidently never more than a small metal protrusion around which traffic flowed.) "Sleeping policemen," on the other hand, wouldn't emerge for another several decades. I don't know where in the English-speaking world the expression originated, though the UK seems likely. The earliest British cite for the term currently given by the OED is from 1973, but this can no doubt be antedated, perhaps by a decade or so. The earliest US cite I've found so far is from Bennington, Vermont in 1967:

Bennington (Vt.) Banner, May 11, 1967, p. 4

Building big bumps -- known as sleeping policemen -- in the streets of Old Bennington as a deterrent to speeders would indeed be an effective way to discourage motorists from stomping too hard on their accelerators.

The term was used in various other American municipalities in the late

'60s. To the right is a photo that appeared in the May 4, 1969 Chicago

Tribune showing a "sleeping policeman" on a park road in Decatur,

Illinois, complete with a warning sign very much like the one in the

L.A. Lights advertisement.

The expression didn't seem to have much staying power in the US,

but it caught on in many other parts of the world with more of a British influence, such as Jamaica and Belize. A

Jan. 30, 1968 letter to the editor in the Jamaican newspaper

The Gleaner explained that "many private roads in Kingston have

installed 'Sleeping Policemen'" and urged the local authorities to

install more. A year or two later "sleeping policemen" had indeed

become more prevalent in Jamaica. A Dec. 7, 1969 UPI wire story in the

Oakland Tribune explained: "When you hear a Jamaican talk about his

country's 'sleeping policemen,' he isn't implying that Jamaican lawmen

aren't wide awake. The term 'sleeping policeman' is used to describe

the

hump built across streets to slow down speeders."

While "sleeping policeman" was making its way around the Anglosphere, equivalents in other languages began popping up. Mexico has policia durmiendo, while France and Switzerland have gendarme couché. There's an entry for gendarme couché in the Dictionnaire Suisse Romand, with some discussion of "sleeping policeman" as well. The entry implies that there isn't enough information to determine which expression is a calque of the other, but "sleeping policeman" appears to win out, unless someone can find citations for gendarme couché earlier than those above. It's also notable that couché means 'lying down, resting, recumbent,' a slightly different sense from "sleeping." Equivalents in some eastern European languages seem to have been calqued from the French expression, such as Hungarian (fekvőrendőr), Estonian (lamav politseinik), and Latvian (guļošais policists).

Perhaps if Indonesian had borrowed the more benign French version, with the figurative image of a police officer lying down rather than sleeping, then the cigarette manufacturers wouldn't be threatened with legal action now. Then again, I doubt the police force would want to be accused of lying down on the job, regardless of whether there's any snoozing going on.

Posted by Benjamin Zimmer at March 14, 2007 04:42 PM