April 24, 2007

1595 is available, but 1975 isn't

You can blame Thor Power Tool Company v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, or Kahle v. Gonzales, or Murphy v. Everybody. But whoever or whatever is responsible, it's bizarre.

In yesterday's post on Ezra Pound at PENNsound ("God's own Englishman with a tube up his nose", 4/23/2007), I mentioned Derek Attridge's 258-page monograph "Well-Weighed Syllables: Elizabethan Verse in Classical Metres", Cambridge University Press, 1975. I bought it for $22.50 in 1975, and remembered it well enough to cite it in my post. Looking it up on line, I discovered that it's out of print, but amazon.com offers us four used copies for between $175 and $179.98, while at alibris.com, there's one copy for $179.93. AbeBooks.com comes up with nothing.

Here's the dust-jacket blurb, copied by hand from my copy:

Sidney's statement in his Apology for Poetry that quantitative verse on the Latin model is more suitable than the accentual verse of the English tradition 'lively to expresss divers passions, by the low and lofty sound of the well-weighed syllable', is only one of numerous assertions of the superiority of classical over native metres made by English scholars and poets during the Renaissance, stretching from Roger Ascham some twenty years earlier to Ben Jonson some fifty years later. Yet this widely-held view appears to modern eyes a perverse eccentricity, and the substantial body of English verse in classical metres produced in this period by a host of writers has long baffled commentators by its apparent disregard of elementary metrical principles.

Dr. Attridge argues that the impulse to write vernacular poetry in classical metres was not an aberration, but a natural outcome of the way in which Latin was read and taught during the Renaissance, giving rise to a conception of metre very different from that which we take for granted today. This enables us to understand not only the low estimate of English accentual verse held by many educated Elizabethans, but also the particular forms which the experiments in English classical verse took.

Dr. Attridge also relates the quantitative movement to broader trends in Elizabethan taste (of which it is a particularly illuminating manifestation), and shows how the sudden decline of the movement was part of a more general change in sensibility at the end of the sixteenth century.

Apparently market forces don't apply to university presses. Given that the marketplace sets the value of used copies of this work at $175 or so, you'd think that Cambridge University Press would sell digital copies for some lesser sum, perhaps making their whole backlist available on a subscription basis to libraries, as EEBO does with works much longer out of print; or perhaps they could turn their out-of-print works over to a just-in-time publisher, as MIT Press has done.

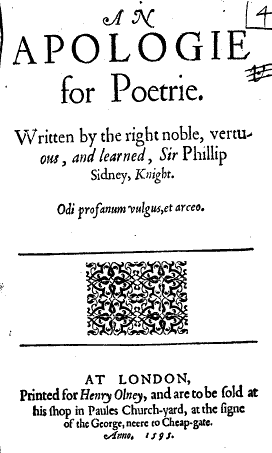

Ironically, Sir Philip Sidney's views on English metrics, originally published in 1595, are easily available to us via Early English Books Online:

And from the OCR'ed version we can even snarf the passage from which Attridge took his title:

Vndoubtedly, (at least to my opinion vndoubtedly,) I haue found in diuers smally learned Courtiers, a more sounde stile, then in some professors of learning: of which I can gesse no other cause, but that the Courtier following that which by practise hee findeth fittest to nature, therein, (though he know it not,) doth according to Art, though not by Art: where the other, vsing Art to shew Art, and not to hide Art, (as in these cases he should doe) flyeth from nature, and indeede abuseth Art.

But what? me thinks I deserue to be pounded, for straying from Poetry to Oratorie: but both haue such an affinity in this wordish consideration, that I thinke this digression, will make my meaning receiue the fuller vnderstanding: which is not to take vpon me to teach Poets hovve they should doe, but onely finding my selfe sick among the rest, to shewe some one or two spots of the common infection, growne among the most part of VVriters: that acknowledging our selues somwhat awry, we may bend to the right vse both of matter and manner; whereto our language gyueth vs great occasion, beeing indeed capable of any excellent exercising of it. I know, some will say it is a mingled language. And why not so much the better, taking the best of both the other? Another will say it wanteth Grammer. Nay truly, it hath that prayse, that it wanteth not Grammer: for Grammer it might haue, but it needes it not; beeing so easie of it selfe, & so voyd of those cumbersome differences of Cases, Genders, Moodes, and Tenses, which I thinke was a peece of the Tower of Babilons curse, that a man should be put to schoole to learne his mother-tongue. But for the vttering sweetly, and properly the conceits of the minde, which is the end of speech, that hath it equally with any other tongue in the world: and is particulerly happy, in compositions of two or three words together, neere the Greek, far beyond the Latine: which is one of the greatest beauties can be in a language.

Now, of versifying there are two sorts, the one Auncient, the other Moderne: the Auncient marked the quantitie of each silable, and according to that, framed his verse: the Moderne, obseruing onely number, (with some regarde of the accent,) the chiefe life of it, standeth in that lyke sounding of the words, which wee call Ryme. VVhether of these be the most excellent, would beare many speeches. The Auncient, (no doubt) more fit for Musick, both words and tune obseruing quantity, and more fit liuely to expresse diuers passions, by the low and lofty sounde of the well-weyed silable. The latter likewise, with hys Ryme, striketh a certaine musick to the eare: and in fine, sith it dooth delight, though by another way, it obtaines the same purpose: there beeing in eyther sweetnes, and wanting in neither maiestie. Truely the English, before any other vulgar language I know, is fit for both sorts: for, for the Ancient, the Italian is so full of Vowels, that it must euer be cumbred with Elisions. The Dutch, so of the other side with Consonants, that they cannot yeeld the svveet slyding, fit for a Verse. The French, in his whole language, hath not one word, that hath his accent in the last silable, sauing two, called Antepenultima, and little more hath the Spanish: and therefore, very gracelesly may they vse Dactiles. The English is subiect to none of these defects.

Too bad we can't resurrect Henry Olney and put him to work monetizing the CUP backlist. Or perhaps we need to resurrect Thomas Jefferson and put him to work refreshing the tree of liberty with the blood of copyright lawyers.

[It should go without saying that this would be purely intellectual blood, and no lawyers (who are as likely to be fine human beings as anyone else is) are to be harmed in the process.]

Posted by Mark Liberman at April 24, 2007 07:57 AM