March 18, 2008

More functional neuroanatomy of science journalism

Some people believe that far-reaching political conspiracies are preventing scientists from discovering and revealing the truth. Ashley Herzog, a journalism major and staff writer at the The (Ohio University) Post, puts this theme front-and-center in her 3/13/2008 article headlined "The Other Side: Despite feminist denial, sexes are wired differently":

Some people believe that far-reaching political conspiracies are preventing scientists from discovering and revealing the truth. Ashley Herzog, a journalism major and staff writer at the The (Ohio University) Post, puts this theme front-and-center in her 3/13/2008 article headlined "The Other Side: Despite feminist denial, sexes are wired differently":

How long before feminists try to censor this? Last week, Science Daily reported on a study from Northwestern University that proved “that girls have superior language abilities than boys ... and gender differences in language appear biological.” Through MRI scans, the researchers discovered that girls’ brains work harder and use more areas during language tasks than boys’ — leading them to conclude that “boys’ and girls’ brains are different.”

This is bad news for feminists, who insist that men and women are really the same (besides the obvious physical distinctions), and that any differences are the products of socialization, “gender roles” and discrimination—and any scientist who suggests otherwise will be punished. We’ll probably never know how great a role biology plays in gender differences, because feminists try to prevent anyone from researching it.

Let me me observe in passing that Ms. Herzog also exhibits the peculiar "brain differences must be innate" idea that I discussed last week in "The functional neuroanatomy of science journalism", 3/12/2008. What got her revved up was a Northwestern University press release reprinted at Science Daily as "Boys' And Girls' Brains Are Different: Gender Differences In Language Appear Biological", 3/5/2008, which starts like this:

Although researchers have long agreed that girls have superior language abilities than boys, until now no one has clearly provided a biological basis that may account for their differences.

For the first time -- and in unambiguous findings -- researchers from Northwestern University and the University of Haifa show both that areas of the brain associated with language work harder in girls than in boys during language tasks, and that boys and girls rely on different parts of the brain when performing these tasks.

"Our findings -- which suggest that language processing is more sensory in boys and more abstract in girls -- could have major implications for teaching children and even provide support for advocates of single sex classrooms," said Douglas D. Burman, research associate in Northwestern's Roxelyn and Richard Pepper Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders.

Braving the feminist hordes, Nikhil Swaminathan at Scientific American also picked up on this press release ("Girl Talk: Are Women Really Better at Language?", 2/5/2008), as did Constance Holden at Science ("He Heard, She Heard", 2/7/2008).

It's true that this story has not yet made as big a splash in the popular press as its authors clearly hoped. On the other hand, neuroscientists are by no means being prevented from researching the biology of sex differences. It's hard to think of any topic that has been getting more study recently, at least among questions without direct pharmacological or clinical applications. And the results often get widespread press coverage, as regular readers of this weblog know. Nor do I know of any cases where scientists have been "punished" for research suggesting that aspects of gender differences are biologically determined -- indeed some well-respected scientists, like Doreen Kimura and Simon Baron-Cohen, have based successful careers on research that argues exactly this.

But in the interests of protecting truth from politics, let's take a look at the paper under discussion in this case. It's Douglas D. Burman, Tali Bitan and James R. Booth, "Sex differences in neural processing of language among children", Neuropsychologia, available online 4 January 2008.

In order to help Ms. Herzog to defeat any antiscientific individuals, feminist or otherwise, who might want to prevent access to this research, I've made a .pdf available here without subscription hindrance. But in fact, after reading the paper, I'm at a loss to see why even the most ardent feminazi in Rush Limbaugh's anxiety closet would want to suppress it.

It's an fMRI study involving 31 girls and 31 boys, ranging from 9 to 15 years in age.

Two language judgment tasks were used. Orthographic judgment (“spelling”) tasks required a subject to judge whether two words presented sequentially shared all letters after the first consonant or consonant cluster. ... In the phonology judgment (“rhyming”) tasks, the subject had to determine whether two sequential words rhymed. ... A visual and an auditory version of each task were presented. ...

In addition, a perceptual control task (24 trials) was used for examining the effect of nonlinguistic sensory processing in each modality. In the visual modality, two visual stimuli were presented sequentially, each consisting of three rearranged letters that bore no resemblance to alphabetic stimuli; in the auditory modality, two triplets of pure tones were presented. The subject indicated whether the second triplet matched the first.

The first thing to observe is that there was no significant sex difference in accuracy on these tasks:

As the authors put it,

Performance on the language tasks performed in the scanner was analyzed with an ANOVA using factors of sex (male, female), age (9, 11, 13, 15 years), and task/modality combinations (auditory rhyming, auditory spelling, visual rhyming, visual spelling). The ANOVA for performance accuracy showed a main effect of age (F[3,155] = 11.264, p < 0.001) and task (F[3,155] = 28.726, p < 0.001). No significant effects on accuracy were observed for sex or its interaction with age or task.

There was a significant difference in reaction time, on the perceptual control tasks as well as the spelling and rhyming tasks: the girls were generally faster, by about 100-200 msec. This was a fairly large effect -- but not one that is consistently found in such studies, as in this table of results from G. Andreou and A. Karapetsas, "Accuracy and Speed of Processing Verbal Stimuli Among Subjects with Low and High Ability in Mathematics", Educational Psychology, 22(5), 2002, where the difference goes in the other direction:

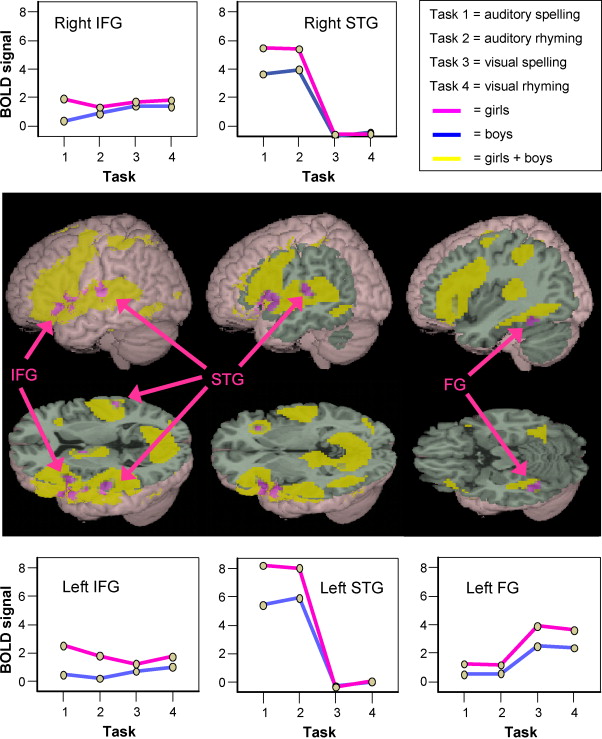

In the Burman et al. study, the fMRI patterns were broadly similar between the sexes, with two particular areas showing greater bilateral activation for the girls in the auditory tasks, and one area showing greater (left-hemisphere) activation for the girls in the visual tasks:

(Unfortunately, there are no standard deviations or other measures of variability from which we could calculate effect sizes.) The authors' description:

Activation across both language judgment tasks and sensory modalities was elicited across all age groups irrespective of sex (yellow in brain images), but girls (pink) showed significantly greater activation than boys (blue) in bilateral regions of IFG and STG as well as left FG. Task, modality, age, and sex were entered into an ANCOVA model with accuracy as a covariate. Graph data were derived from ROI analysis of five regions showing significant sex effects (p < 0.005 with a Bonferroni correction); the BOLD signal represents the estimated partial means derived from the mean activity of each region-of-interest after removing variance attributable to age and accuracy.

Note by the way that

Sex differences were also evident from activation in the perceptual control tasks. Girls showed greater activation than boys in the left occipital and fusiform gyri for visual stimuli, whereas they showed greater activation than boys bilaterally in the superior temporal gyrus for auditory stimuli.

As the authors point out, it's not clear what these differences mean.

Increased brain activation may reflect either greater task difficulty or improved processing and performance. Evidence suggests that increased fusiform and inferior frontal activation by girls is beneficial for performance. [...] Apparently the increased hemodynamic response observed among girls reflects processes relevant to skilled language performance beyond what was required to accurately perform the tasks used here.

In other words, rather than exhibiting (in this experiment) "superior language abilities", the girls' brains appear to be working harder to achieve the same average results (at least in terms of task accuracy -- they did show faster average reaction times).

Of course, increased brain activation might also reflect greater attention to the task, "beyond what was required to accurately perform [it]". Is there any indication that attention might have been an issue in this experiment? Maybe; the authors explain that results from some subjects were excluded

due to excessive movement (>4 mm within a run), poor signal-noise-ratio in primary visual cortex or primary auditory cortex in the complex perceptual condition (more than 2 standard deviations below the mean), or near-chance accuracy on a task (<60%). Functional MRI data from 43 subjects in the auditory rhyming task (19 boys and 24 girls), 42 subjects in the auditory spelling task (17 boys and 25 girls), 54 subjects in the visual rhyming task (26 boys and 28 girls), and 48 subjects in the visual spelling task (25 boys and 23 girls) were used in our analyses.

In other words, out of 31x4 = 124 possible subject-by-task datasets for each sex, 37 of the boys' sessions were excluded, vs. 24 of the girls' sessions. This would be consistent with lower levels of motivation and attention from the boys, resulting in more fidgeting in the magnet, more "near-chance accuracy", etc. -- and perhaps a somewhat lower level of motivation and attention even among those whose data was not thrown out.

For completeness, I should mention that there's a general sex difference in cerebral blood flow, discussed here a couple of years ago ("The vast arctic tundra of the male brain", 9/6/2006), whose nature and interpretation is apparently unclear, and whose relationship to the differences found in this study is certainly not clear to me.

The most interesting part of the Burman et al. study was what happened when they looked for correlations between individual differences in task performance and individual differences in localized fMRI activity. What they found was that these correlations were different, overall, between the boys and the girls. Here's their discussion:

Among boys, brain areas required for accurate performance of a language task depended on the modality of the presented words; accurate responses to visually presented words utilized visual association cortex and posterior parietal regions, whereas accurate response to auditory word forms utilized areas involved in auditory and phonological processing. In boys, correlations with accurate spelling and rhyming judgments were not seen. By contrast, accuracy for rhyming and spelling judgments among girls were each correlated with activation in the left inferior frontal gyrus and the left middle temporal/fusiform gyrus, regardless of stimulus modality. These same areas were also correlated with accuracy during auditory word tasks, perhaps reflecting automatic access of spoken words to the linguistic system (Cobianchi & Giaquinto, 1997; Pulvermuller & Shtyrov, 2006). Among girls, no correlation with accuracy was observed across visual tasks, indicating that accurate performance on visual word tasks involving different linguistic judgments was not limited by visual processes.

[...]

The sensory association areas correlated with accuracy in boys have been implicated in auditory and visuospatial processing, respectively (LaBar, Gitelman, Parrish, & Mesulam, 1999; [Poeppel et al., 2004] and [Simos et al., 2000]). Correlation of performance accuracy with activation in these sensory association areas may reflect the quality of sensory processing before the word is accessed by the language network. If boys do not convert sensory information to language as well as girls, the quality of sensory processing in sensory association areas may act as a bottleneck that limits the accurate representations of words, thereby limiting performance accuracy. Sex differences for the perceptual controls (as well as words) suggests that boys are indeed less effective in sensory processing. If improvement in sensory processing during maturation eliminates the bottleneck in boys, then accurate performance should no longer be limited by (and correlated with) activity in the sensory association cortex, allowing accurate performance to reflect activity in the language network. This may indeed be the case. In a mixed-sex group of adults, accuracy of spelling and rhyming judgments are correlated with activation in linguistic regions of the fusiform and superior temporal gyri, respectively (Booth et al., 2003), suggesting that adult males and females depend on the same specialized language areas. If so, sex differences in linguistic activation during childhood may reflect developmental differences in maturation rate ([Blanton et al., 2004] and [Cohn, 1991]).

This might all be true. But all that Burman et al. tell us is that there was a statistically-significant group difference. Before drawing any very strong conclusions from this research -- for example, that it means something for classroom practice -- I'd like to know more about how big these sex differences in correlations between accuracy and local activation really are, and how the within-group differences compare to the between-group differences.

And I'd like to be more confident that the whole thing is not the result of differences in attention /motivation in the setting of this experiment. For example, if (some of) the boys were not paying attention on some of the trials, then there could be quite a strong correlation between their overall performance and their average level of activation in sensory cortex, and too much noise to see a correlation with activation in cross-modal language areas.

Let's go back to Ms. Herzog's article (she's the Ohio journalism major), which goes on to decry the treatment of Larry Summers, and puts Dr. Louann Brizendine forward as a brave anti-feminist hero:

Predictably, scholars who aren’t intimidated by feminists are ridiculed and ostracized. Last year, Louann Brizendine, a neuropsychiatrist at the University of California San Francisco, published her book The Female Brain, which is based on more than a thousand studies from the fields of genetics, neuroscience and endocrinology. After decades of research, Brizendine concluded that male and female brains are both structurally and hormonally different. As she wrote, “there is no unisex brain…girls arrive already wired as girls, and boys arrive already wired as boys.”

Feminist book reviewers and columnists — who don’t have degrees in neuroscience, just a faith-based belief that socialization accounts for all gender differences — savagely attacked Brizendine and the book, calling it “garbage” and “scary.” Displaying feminists’ typical open-mindedness to scientific facts, one reviewer claimed that “I found my self slamming the book down and walking out of the room in an aggressive and angry mood.”

With this level of censorship, it’s no wonder that scientists are expected to hide research that suggests men and women are innately different. We can rest assured that a book like The Female Brain will never be assigned reading in a college classroom. Meanwhile, sociology and women’s studies textbooks are filled with laughably false assertions about gender. Legitimate scholarship is being sacrificed on the altar of political correctness.

My own impression is that most reviewers were very kind to Dr. Brizendine, and the less they knew about neuroscience, the kinder they were. (Some reviews are discussed in posts linked here.) Rebecca Young and Evan Balaban, whose degrees are in either in neuroscience or in closely related areas, reviewed Brizendine's book in Nature, under the headline "Psychoneuroindoctrinology". It's true that they were not so kind. But rather than slamming the book down and walking out angry, they said that the book "fails to meet even the most basic standards of scientific accuracy and balance", "is riddled with scientific errors", and "is misleading about the processes of brain development, the neuroendocrine system, and the nature of sex differences in general".

It may well be true that "women's studies textbooks are filled with laughably false assertions about gender" -- I've never read any of these textbooks -- but the only example that Ms. Herzog gives is an undocumented anecdote from a work of a rather different kind:

In their book Professing Feminism, women’s studies professors Daphne Patai and Noretta Koertge described a confrontation with a fellow feminist. The feminist was angry over suggestions that women should breast-feed babies, because — in her words — “research shows that men can lactate, too.”

The problem with The Female Brain, at least in the parts of it I've checked, is not that it contravenes feminist orthodoxy. On the contrary, it promotes a set of gender stereotypes that I associate with at least some feminist authors (for instance, that men are competitive while women are cooperative). And just like Ms. Herzog's stereotype of "women's studies textbooks", it was full of strong general statements, often quantitative in nature, that are either unsupported or false -- sometimes, to use Ms. Herzog's term, laughably so. At least one of these false claims -- that men use only a third as many words per day as women -- was withdrawn in later editions, but many others remain, such as the claim that men on average think of sex every 52 seconds, which appears to be wrong by more than 20,000 percent. (For further details, see the posts linked here.)

I'm glad to see a budding journalist who is committed with such passionate intensity to the political independence of science. We scientists are going to need all the support we can get in standing up to political influence as well as cultural orthodoxies of various kinds. But let me appeal to Ms. Herzog, and to journalists at all career stages, to start reading the original sources, not just the press releases, and to apply to arguments from all sources the same informed skepticism that you've learned to apply to politicians that you dislike.

Posted by Mark Liberman at March 18, 2008 07:00 AM