January 15, 2007

Martin Luther King's rhetorical phonetics

In the early 1960s, millions of Americans were ready to listen to Martin Luther King's message, and the way that he delivered that message helped us to hear it.

In the early 1960s, millions of Americans were ready to listen to Martin Luther King's message, and the way that he delivered that message helped us to hear it.

Listen to these two phrases from the famous "I have a dream" speech, delivered on August 20, 1963 at the Lincoln Memorial. The first phrase, "I am happy to join with you today", is his opening. The second, "when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet", is from his peroration, just before the immortal ending "free at last".

| "I am happy to join with you today" |

| "when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet" |

His timing is eloquent: he speeds up and slows down in a way that conveys how his sentences are put together. Every fluent speaker does this to some extent, and he does it abundantly and at the same time precisely. But within most phrases in this speech, his pitch is relatively level, almost as if he were chanting or singing rather than speaking.

In particular, his phrases often end with a sustained or slightly falling pitch, instead of the steeper relaxation to low pitch that English phrases usually have. Because the expected falls are missing, some of his sutained final syllables (e.g. "today" in the opening phrases) may sound to some people as if they go up. But listen carefully, and look at the pitch contours:

Of course, King's individual phrases in this speech do have a melody -- though sometimes a subtle one -- that helps convey his message. And he varied the overall pitch range much more widely from section to section of the speech, as effective speakers since time immemorial have done to embody the ebb and flow of ideas and emotions. But there was something about the way that he chanted each phrase, like a song or a prayer, that commanded attention and memory.

For an example of a contrasting rhetorical style -- one that was more familiar to most white Americans, at least in the north -- listen to the opening phrase and part of the peroration of another justly famous early-60s speech, John F. Kennedy's Inaugural Address, delivered January 20, 1961. (The two MLK phrases are numbers 1 and 2 in the panel below, and the two JFK phrases are numbers 3 and 4.)

| "I am happy to join with you today" |

| "when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet" |

| "We observe today" |

| "ask not what your country can do for you" |

Kennedy also uses pitch pitch and time effectively, but in a different way. As the pitch tracks below illustrate, JFK tends to use more within-phrase pitch modulation, and his non-final phrases are more likely to end in a fall-rise or a fall, without the singing or chanting quality of MLK's public rhetoric:

This little breakfast-time exercise in rhetorical phonetics is anecdotal and allusive at best, so I put it forward only tentatively, as an invitation to someone to do better. It's a curious fact about modern intellectual life, though, that such analysis is not commonly done in a more systematic and scientific fashion. The people who are interested in rhetoric don't (as far as I can tell) know how to use the methods of modern instrumental phonetics and statistical modeling, while the phoneticians don't see rhetoric as within their purview. I doubt that this disconnection would have happened in any earlier era.

One more small point. It's an obvious point, but too often forgotten. The way that someone speaks in a given context -- including the context of the phonetics lab -- is not a fixed and invariant property of their individual essence. It's a way of behaving that depends not only on who they are, but also on what they're saying, where they're saying it, why they're saying it, and who the audience is. Among other things.

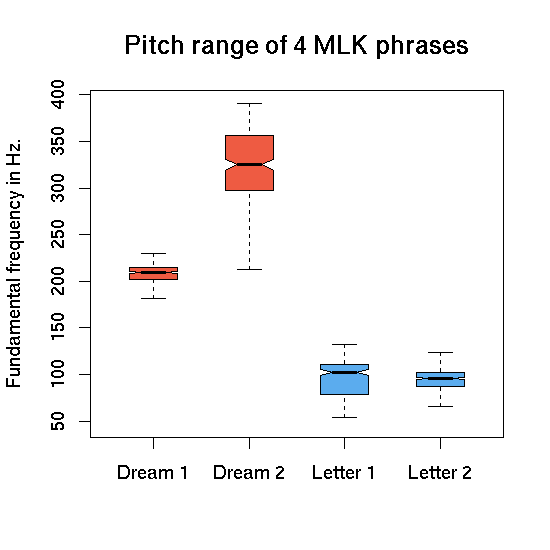

We can see one small example by comparing the two phrases from MLK's "Dream" speech with two phrases from his reading of the "Letter from Birmingham Jail", sent April 16, 1963.

| "I am happy to join with you today" |

| "when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet" |

| "my dear fellow clergymen" |

| "Seldom do I pause to answer criticism of my work and ideas" |

It's the same man, and the same voice, but a lot of things are different.

For one thing, he uses within-phrase pitch modulation to a greater (proportional) extent, and a larger fraction of his phrases end in English-typical final falls, as the pitch contours for these two phrases suggest:

For another thing, his overall pitch range is radically lower. Within each recording, his pitch range expands and contracts, and goes up and down, in the usual rhetorical parallelism of sound and sentiment. But his performance of the letter -- a sober and intimate communication, read as if to a small nearby audience -- is pitched at a whole different level from his performance at the Washington Memorial.

This boxplot of pitch values from the four sample phrases illustrates the point:

I said that this kind of variation is obvious, and also that it's too often forgotten. Here's an example of how phoneticians often forget it, or more precisely, pretend that it's not true. The graph below is from a meta-analysis that combine data from many studies of male and female fundamental frequency in speaking:

The basic interpretation is clear and also true:

- Children speak with higher pitch than adults, due to smaller body size and smaller larynx dimensions;

- As children pass puberty, average male and female pitch values diverge, with male pitches being lower due to the effects of testosterone on larynx growth during puberty (the "voice changing" effect);

- The voices of older people tend to get slightly higher, probably due to decreased tissue elasticity.

However, something important is left out here. The implication of the plot is that a person of a given sex and age has a specific and predictable F0, characteristic of them as a member of the group. This leaves out the wide range of variation in characteristic speaking pitch among (say) 20-year-old males -- but it's normal, if sometimes misleading, to simplify such plots by showing only the means and ignoring the distribution of values. [Actually, plot does show error bars, but they're misleadingly small, in my judgment.] The same thing might happen if we were plotting height as a function of sex and age -- and it might well be the most appropriate way to present the information.

But in this case, something else is left out as well. Someone's height doesn't vary much from context to context within a short period of time,the way that their pitch does. As the plot of MLK's "Dream" and "Letter" performances shows, you can't characterize someone's pitch -- even as an average -- without considering their utterance's context, purpose, style, audience and so on. Note in particular that the average pitches of MLK's "Dream" speech are well above the line of pitches given as characteristic for female speakers.

It's certainly true that there's an underlying laryngeal biology of age and sex that underlies, at least qualitatively, the last plot above. That's presumably because the measurements were made in roughly similar settings, to which the speakers of different ages and sexes reacted in roughly similar ways.

But in general, in order to understand behavioral measurements from human groups, whether biologically or culturally defined, we need to think about what the contexts were, and how the people interpreted and responded to them. And whatever we learn about the group effects, we need to remember one of Martin Luther King's other memorable phrases:

Posted by Mark Liberman at January 15, 2007 11:15 AMI have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.