April 24, 2004

Little words

I was puzzled by one aspect of a recent post of Mark Liberman's on changes in textual complexity. Mark's post is part of a thread which Geoff Nunberg extended most excellently. See also Paglia's original, Semantic Compositions' discussion, and a meta-comment from Mark.The Paglia original is far from a coherent argument for anything, so that merely attacking her premises seems to miss the point, although I agree with her conclusion that `language must be reclaimed from the hucksters and the pedants' (at least on my interpretation of what she means). However, I won't have any more to say as regards Paglia's premises, argument or conclusions here. What I want to discuss is a bunch of little words that Paglia probably couldn't care less about.

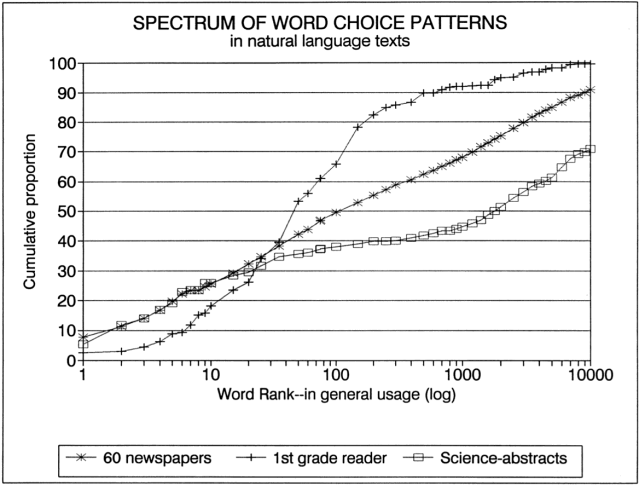

Mark's argument concerned the lack of evidence that popular culture is in decline, and, in particular, the lack of evidence that school texts are being dumbed down. He included a pretty graph showing how words are distributed in different text genres. After a little while digesting the graph, understanding the log scale etc. (ahh, so that's what a language log is...), I decided there was something about it that confused me, although unconnected with Mark's main point. It seems that 1st grade readers have relatively fewer very high frequency words than do newspapers and scientific abstracts. Funny, without thinking about it I would have guessed just the opposite.

Here is the graph (from Marty White at Cornell, and found in this nice document describing White's research):

As we move along the x-axis, we consider successively less frequent words. For a given word rank, the height of the graph tells us what proportions of words in the text have that frequency or greater. Thus we can see that the 1000 most common words in 1st grade readers account for over 90% of the text, while the top 1000 account for less than 70% in newspapers, and less than 50% in scientific abstracts (from Nature, not Science as you might interpret the legend to mean). This is supposed to provide an objective justification for the intuition that 1st grade readers are less complex than newspapers which are less complex than scientific abstracts.

So far, so good. But what disturbed me is that the 1st grade reader line in the graph starts out so amazingly low, and only reaches the others after rank 25 or so. While for newspapers and scientific abstracts the 10 most frequent words account for about 25% of all words, the 10 most frequent words in 1st grade readers together account for only 15% of all words. Couldn't this be used as an argument that the kiddy texts are more complex than the grown-ups' texts?

I don't know whether anyone else was puzzled by this. Maybe co-loggers and readers with a statistical bent will think it obvious and unsurprising. But it puzzled me. So in order to restore order to my world I dreamed up a hypothesis. The idea is that because sentences in kids texts are syntactically much simpler than sentences in adult texts, and involve less sophisticated connections between sentences and between the proposition expressed and prior world knowledge, the kiddy texts have much less need for words like the, of, and and to - the four most common words in the Brown corpus, and I guess probably also in the children's texts that White surveyed. Which leads me to...

| The little words do

big things hypothesis:

the most frequent words in a

text are closed class words that are

essential for stringing together complex sentences and texts, and their

frequency

is proportional to (or at least some upward monotone function of) the

average syntactic complexity of the text. |

So if we're worried about the complexity of kids' texts, maybe we shouldn't ask whether the texts have enough big words, but whether they have enough little ones.

Posted by David Beaver at April 24, 2004 05:35 PM