January 02, 2007

Vicky Pollard's revenge

A couple of weeks ago, we batted around the witless lead of a BBC story about an effort to improve British kids' vocabulary:

A couple of weeks ago, we batted around the witless lead of a BBC story about an effort to improve British kids' vocabulary:

Britain's teenagers risk becoming a nation of "Vicky Pollards" held back by poor verbal skills, research suggests.

And like the Little Britain character the top 20 words used, including yeah, no, but and like, account for around a third of all words, the study says. [emphasis added]

Arnold, Geoff and I pointed out that this kind of 20-word vocabulary coverage is true of pretty much everybody, including BBC News and the author of the study ("Britain's scientists risk becoming hypocritical laughing-stocks, research suggests"; "Only 20 words for a third of what they say: a replication"; "An apology to our readers").

But this story also introduced me to Vicky Pollard as character and a stereotype -- and one of the things that I learned, watching Vicky Pollard clips on youtube, is that her character is in fact portrayed as hyper-verbal. Her speech is full of stigmatized lower-class and youth-culture features; but her biggest communicative problem is using too many of the wrong words at the wrong time. So I decided to take a quick look at some measures of her word usage -- partly to confirm my impressions, and partly as a further illustration of some of the issues involved in quantifying vocabulary.

For readers outside of Britain, let's start with an introduction to Vicky. She's a character on a BBC radio and TV show called "Little Britain", played in drag by Matt Lucas as an irresponsible, overweight, rude teenage bully with six (or perhaps even twelve) children and a predilection for shoplifting. She's associated with a few catch-phrases -- "Yeah but no but yeah but...", "Oh my god I so can't believe you just said that!""Don't go giving me evils!" -- and this seems to be what lies behind the BBC News assumption that her vocabulary is generally impoverished.

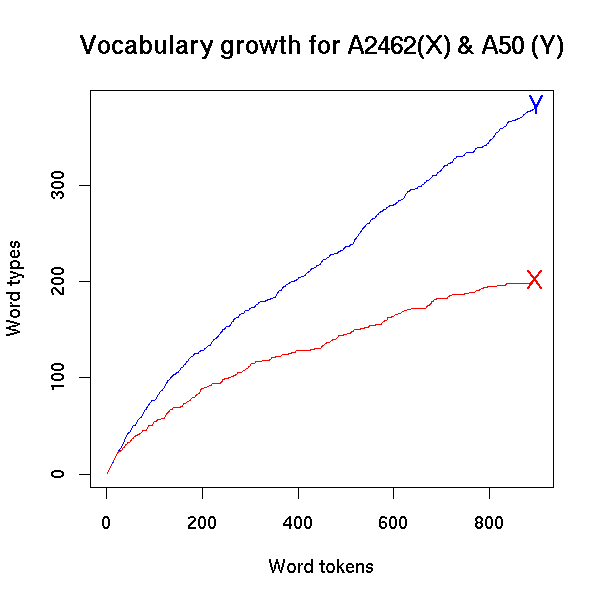

But how can we really tell whether or not this assumption is wrong? We need a way to measure her vocabulary and compare it with the vocabulary of other (real or fictional) people. One approach starts by looking at how the number of distinct words ("word types") grows as more and more words are spoken (or written). A graphical representation of this function is called a "type/token plot" or a "vocabulary growth plot". Let's look at some examples of vocabulary growth plots, starting with the transcripts of telephone conversations from the published Fisher 2003 corpus.

Mr. Y was the A side of conversation number 50. He was a 43-year-old male with 14 years of education, and on his side of that conversation, he produced 899 total words ("word tokens") involving 384 different vocabulary items ("word types"). There were fewer "types" than "tokens" because 34 of his 899 words were the, 32 were you, and so on. When Mr. Y had produced 100 word tokens, they fell into 77 types; at 200 tokens, he was at 128 types; and so on.

Ms. X, the A side of conversation 2462, was a 21-year-old-female with 14 years of education. She produced 895 word-tokens of 202 lexical types. At 100 tokens, she'd produced 55 word types; at 200 tokens, she was at 89 types.

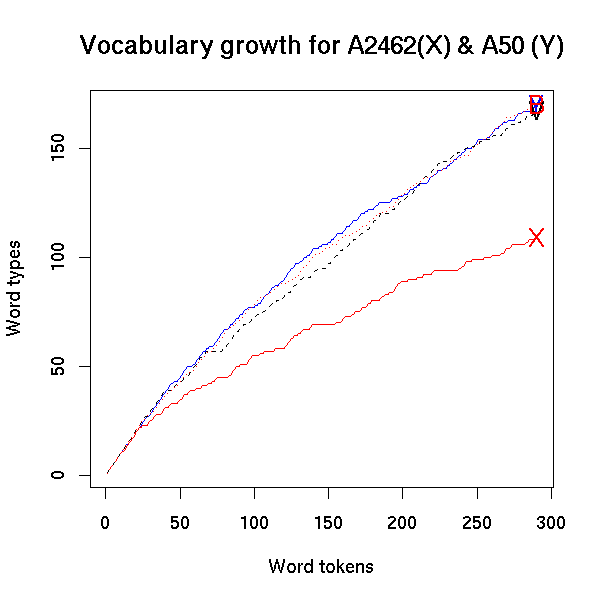

If we plot the vocabulary growth curves for these two individuals, we get something like this:

You can get a sense of why the two vocabulary growth curves came out differently by looking at a few selected conversational turns from Ms. X and Mr. Y:

| X: | Yeah I have seen them before, but I don't know, I don't really have time to watch t.v. so I mean I watch them because they're pretty entertaining, but you know I wouldn't actually plan you know to to to plan a time to um to watch them or something like that, no. |

| I don't know I mean they're just entertaining that that's all it is, I don't think that there's really that these people are really in danger or anything, so mn it's just pure entertainment to me. | |

| So I cannot you know devote my whole attention to whatever's on t.v. 'cause you know there's other stuff that you know I just want to do at the same time, so if I'm watching like news or if I'm watching you know like a talk show or something, I can do everything at once. If I'm watching a movie or if I'm watching, I don't know, something that, you know, I can't really do it um so. | |

| Y: | Precisely, plus let us face it, there aren't any commercials on t.v. telling us say something bad about someone else. No, to do that you've got to watch things like America's Stupidest Home Videos or Cops -- an exotic form of gossip, you know. |

| I'd love to have something where you know we just stick a little old lady with a flat tire by the side of the road and a camera watching. | |

| So unfortunately I came to the conclusion that uh in this day and age what is really needed is the sleazy scandalous tell all about Camelot |

It's important to stress that the numbers from one short passage shouldn't be taken as a stable and reliable characterization of how a given person talks. Ms. X, a 21-year-old college student who "doesn't really have time to watch t.v.", is talking about television programs with a stranger, and she's producing a remarkably small proportion of contentful words. But maybe she's a biochemistry major and would totally max out the vocabulometer if the conversation were to turn to protein phosphorylation sites.

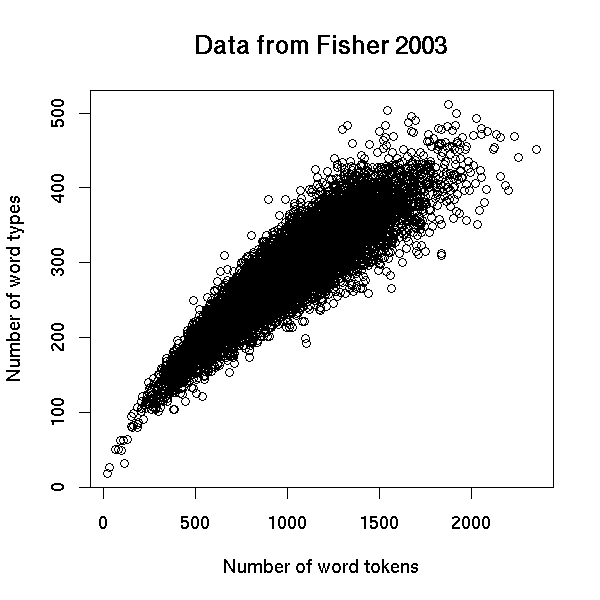

Still, a type-token plot is one way to get a good local picture of how someone is deploying words in speech or writing. The Fisher 2003 corpus involved 11,700 conversational sides, so there are a lot more of these vocabulary growth curves to plot. Such a plot is going to get pretty busy, but we can get a sense of what the distribution of word-type/word-token relationships in this corpus is like by plotting all 11,700 end-points:

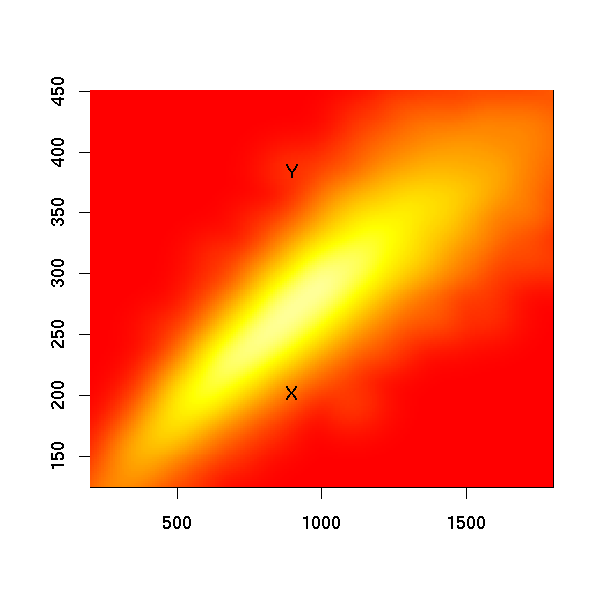

In fact there are still too many datapoints to be able to see the denser regions very clearly. So here's a 2D kernel density plot with Ms. X and Mr. Y plotted on it, showing where their type-token totals fell in the overall distribution:

I've chosen them, of course, to bracket the top and bottom of the word-type distribution in the middle of the word-token range.

There were 762 speakers (out of 11,700) who produced between 875 and 925 word-tokens, inclusive. The average number of word-types for this group was 270, with a standard deviation of 24.

One of these 762 speakers was Mr. Y, the A side of conversation 50. The 384 different word-types that he produced was 4.7 standard deviations above the mean (for the group producing between 875 and 925 word-tokens).

The 202 word-types produced by Ms. X, the A side of conversation 2462, were 2.8 standard deviations below the group mean.

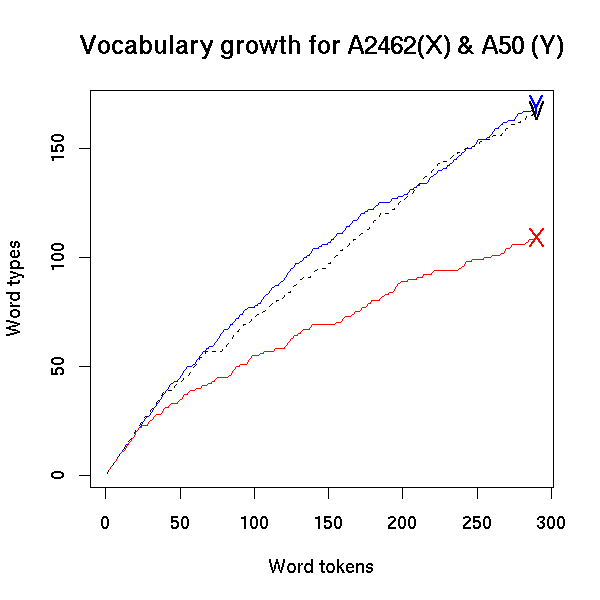

With some difficulty, I transcribed Vicky Pollard's side of the dialogue in a skit about her attempt to get a job as a telephone sex operator. If we plot her vocabulary growth curve on the same scale as Ms. X and Mr. Y, we see that she's running neck-and-neck with Mr. BigWords:

Vicky has certainly got many problems with what she says and how she says it. But a limitation in the number of different words she uses is not one of them. As evidence, let's compare Vicky's vocabulary growth curve in her sex-worker skit with the start of a weblog entry dated 30 Dec 2006, written by a BBC editor, Kevin Bakhurst, about "Saddam's execution".

The Y (for Mr. Y from Fisher A50), the V (for Vicky Pollard) and the B (for Kevin the BBC editor) are all pretty much superimposed.

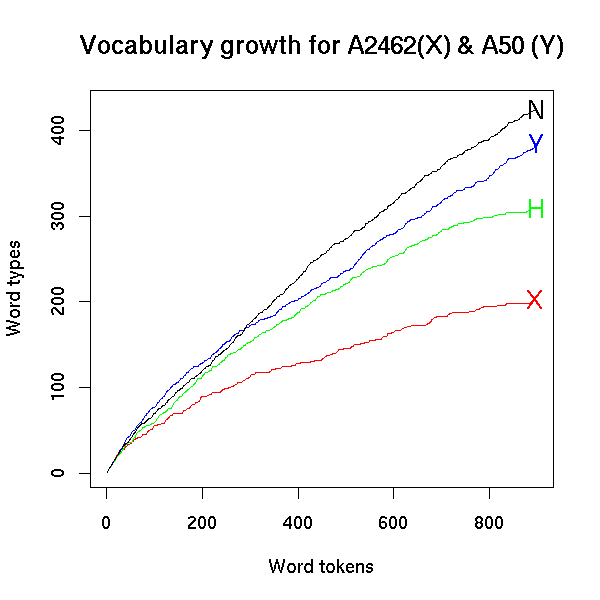

Just to make it clear that there are more than two possible vocabulary growth curves, here's Ms. X and Mr. Y again with the start of chapter 1 of Huckleberry Finn (the H curve) and the start of Geoff Nunberg's essay "Label Pains" (the N curve).

Next: how to fit a model to vocabulary-growth curves, and predict the future.

[The Fisher Corpus is part of a larger collection of recorded and transcribed telephone conversations that has been a favorite subject for Breakfast Experiments™ from Language Log Labs: see

"Young men talk like old women" (11/6/2005)

"Another Breakfast Experiment" (11/8/2005)

"Sex doesn't matter" (11/11/2005)

"Gabby guys: the effect size" (9/23/2006)

"Busy Tongues" (12/31/2006)

]

[Thanks to alert LL readers for pointing out some typos in the first draft of this post. (1) I started with Mr. X and Ms. Y, but then swapped the letters to correspond to the chromosome names, and didn't change all the instances. I think the naming is consistent now. (2) By some trick of the brain and/or fingers, I identified Ms. X as 24 years old in one place and 22 years old in another. When I checked the speaker-demographics database for the published corpus, I discovered that she is in fact listed as 21, which I makes sense for a junior in college, which is what the transcript suggests that she is. Apologies for the errors, and thanks for the peer review, which enabled me to catch and correct the errors within two hours. (It would have been faster, but I was busy with one of my regular jobs.)]

Posted by Mark Liberman at January 2, 2007 07:24 AM