December 26, 2006

Shakespearing the reader's brain: A tragicomedy in three acts

Act I: Denominal verbs and their discontents.

As Eve V. Clark and Herbert H. Clark observed long ago ( "When Nouns Surface as Verbs", Language 55(4) 767-811, 1979),

People readily create and understand denominal verbs they have never heard before, as in to porch a newspaper and to Houdini one's way out of a closet.

English speakers have been doing this sort of thing since they called themselves Angelfolc -- the verb love started life as Old English lufian, from the noun lufu, and that old denominal beat has kept right on going ever since. But in more recent times, this ancient form of linguistic creativity has started to drive some people up the wall. Earlier this year, Ben Zimmer documented an interesting case from the 2006 Winter Olympics ("Odium against 'podium'", 2/15/2006): "a horrible development"; "very distracting"; "Ugh."; "Arrrrgh. Grrrrr."; "Please don't say 'She can definitely podium' again".

The odium is not reserved for brand-new coinages. Geoff Nunberg recently noted that "fully 98 percent [of the AHD usage panel, which he chairs] disapprove of the use of dialogue as a verb, as in Critics have charged that the department was remiss in not trying to dialogue with representatives of the community." And Prof. Paul Brians agrees that alternatives are better:

“Dialogue” as a verb in sentences like “the Math Department will dialogue with the Dean about funding” is commonly used jargon in business and education settings, but abhorred by traditionalists. Say “have a dialogue” or “discuss” instead.

Paul and the AHD panel are giving you sound advice. But it's worth distinguishing between practical advice about life in the real world, and moral evaluation of the people who make that advice necessary. When I advise you to avoid the districts where you're likely to get mugged, I'm not implying that muggers are justified in plying their trade. Both the AHD panel members and Prof. Brians are aware that the use of dialogue as a verb was not invented by 20th-century bureaucrats. The OED gives

1607 SHAKES. Timon II. ii. 52 Var. How dost Foole? Ape. Dost Dialogue with thy shadow?

1741 RICHARDSON Pamela II. 45 Thus foolishly dialogued I with my Heart.

1817 COLERIDGE Biog. Lit. (1882) 286 Those puppet-heroines for whom the showman contrives to dialogue without any skill in ventriloquism.

1858 CARLYLE Fredk. Gt. I. IV. v. 426 Much semi-articulate questioning and dialoguing with Dame de Roucoulles.

We can add this from Alexander Pope (endnote for his translation of Verse 147 of the VIth book of the Iliad, 1714):

Some may think after all, that tho' we may justify Homer, we cannot excuse the Manners of his Time; it not being natural for Men with Swords in their Hands to dialogue together in cold Blood just before they engage. But not to alledge, that these very Manners yet remain in those Countries, which have not been corrupted by the Commerce of other Nations, (which is a great Sign of their being natural) what Reason can be offer'd that it is more natural to fall on at first Sight with Rage and Fierceness, than to speak to an Enemy before the Encounter? Thus far Monsieur Dacier, and St. Evremont asks humourously, if it might not be as proper in that Country for Men to harangue before they fought, as it is in England to make Speeches before they are hanged. [emphasis added]

And from Samuel Richardson's Clarissa (Vol. 1, Letter XVI): "Will he bear, do you think, to be thus dialogued with?"

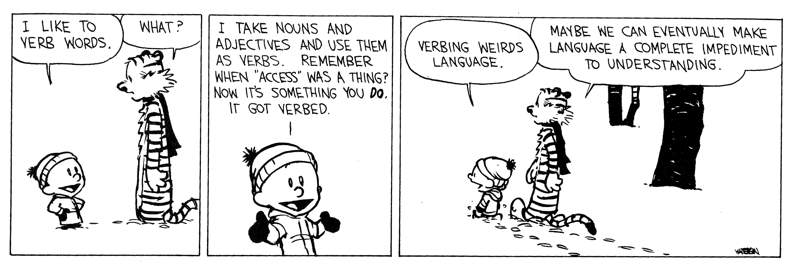

But we're dealing with visceral reactions, not historical citations, and apparently there's something about making new verbs that grates on people in a way that other category shifts don't. A classic Bill Watterson Sunday strip illustrates this mildly transgressive bad-boy vibe:

And Paul Brians, again, understands that this is a district where you're likely to be mugged by the people he calls "conservatives":

“Access” is one of many nouns that’s been turned into a verb in recent years. Conservatives object to phrases like “you can access your account online.” Substitute “use,” “reach,” or “get access to” if you want to please them.

And he's also right that in the particular case of access, the noun-to-verb shift is a fairly recent one. The OED's earliest citation is:

1962 A. M. ANGEL in M. C. Yovits Large-Capacity Memory Techniques for Computing Systems 150 Through a system of binary-coded addresses notched into each card, a particular card may be accessed for read and write operations.

A Google books search suggests that antedating back to 1949 may be possible. But again, this isn't about antiquity, it's about antipathy. Or maybe it's about some other kind of impact: to be precise, the P600.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Act II: The Shakespeared Brain

Philip Davis, an English professor at the University of Liverpool, believes that the "shapes that thoughts take" in literature "[have] a dramatic effect at deep levels". So, according to his article "The Shakespeared Brain", The Reader #23, Fall 2006.:

I took this hypothesis - about grammatical or linear shapes and their mapping onto shapes inside the brain - to a scientist, Professor Neil Roberts who heads MARIARC (the Magnetic Resonance and Image Analysis Research Centre) at the University of Liverpool. In particular I mentioned to him the linguistic phenomenon in Shakespeare which is known as ‘functional shift’ or ‘word class conversion’. It refers to the way that Shakespeare will often use one part of speech - a noun or an adjective, say - to serve as another, often a verb, shifting its grammatical nature with minimal alteration to its shape. Thus in Lear for example, Edgar comparing himself to the king: ‘He childed as I fathered’ (nouns shifted to verbs); in Troilus and Cressida, ‘Kingdomed Achilles in commotion rages’ (noun converted to adjective); Othello ‘To lip a wanton in a secure couch/And to suppose her chaste!’ (noun ‘lip’ to verb; adjective ‘wanton’ to noun). The effect is often electric I think, like a lightning-flash in the mind: for this is an economically compressed form of speech, as from an age when the language was at its most dynamically fluid and formatively mobile; an age in which a word could move quickly from one sense to another, in keeping with Shakespeare’s lightning-fast capacity for forging metaphor. It was a small example of sudden change of shape, of concomitant effect upon the brain. Could we make an experiment out of it?

Well, of course they could:

With the help of my colleague in English language Victorina Gonzalez-Diaz, as well as the scientists, I designed a set of stimuli – 40 examples of Shakespeare’s functional shift. [...] It is not Shakespeare taken neat; it is just based on Shakespeare, with water. But around each of those sentences of functional shift we also provided three counter-examples which were shown on screen to the experiment’s subjects in random order: all they had to do was press a button saying whether the sentence roughly made sense or not. Thus below A (‘accompany’) is a sentence which is conventionally grammatical, makes simple sense, and acts as a control; B (‘charcoal’) is grammatically odd, like a functional shift, but it makes no semantic sense in context; C (‘incubate’) is grammatically correct but still semantically does not make sense; D (‘companion’) is a Shakespearian functional shift from noun to verb, and is grammatically odd but does make sense:

A) I was not supposed to go there alone: you said you would accompany me.

B) I was not supposed to go there alone: you said you would charcoal me.

C) I was not supposed to go there alone: you said you would incubate me.

D) I was not supposed to go there alone: you said you would companion me.

They recorded electroencephalographic signals (EEG) from their subjects, time-registered with presentation of the stimuli, and looked for N400 and P600 event-related potentials (ERPs). The N400 component is a negative-going effect about 400 milliseconds after stimulus presentation, believed to result from "semantic anomaly" -- content that doesn't make sense (van Berkum et al. 1999). The P600 component is a positive-going effect about 600 milliseconds after stimulus presentation, believed to "[reflect] difficulty with syntactic integration processes" -- grammatical shapes that don't fit together (Kaan et al. 2000).

The results were exactly what the ERP literature of the past couple of decades would predict (quoting Davis' Reader article):

(A) With the simple control sentence (‘you said you would accompany me’), NO N400 or P600 effect because it is correct both semantically and syntactically.

(B) With ‘you said you would charcoal me’, BOTH N400 and P600 highs, because it violates both grammar and meaning.

(C) With ‘you said you would incubate me’, NO P600 (it makes grammatical sense) but HIGH N400 (it does not make semantic sense).

(D) With the Shakespearian ‘you said you would companion me’, HIGH P600 (because it feels like a grammatical anomaly) but NO N400 (the brain will tolerate it, almost straightaway, as making sense despite the grammatical difficulty). This is in marked contrast with B above.

Where are Davis and his colleagues going with this?

This is a small beginning. But it has some importance in the development of inter-disciplinary studies – the co-operation of arts and sciences in the study of the mind, the brain, and the neural inner processing of language felt as an experience of excitement, never fully explained or exhausted by subsequent explanation or conceptualization. It is that neural excitement that gets to me: those peaks of sudden pre-conscious understanding coming into consciousness itself; those possibilities of shaking ourselves up at deep, momentary levels of being.

This, then, is a chance to map something of what Shakespeare does to mind at the level of brain, to catch the flash of lightning that makes for thinking. For my guess, more broadly, remains this: that Shakespeare’s syntax, its shifts and movements, can lock into the existing pathways of the brain and actually move and change them – away from old and aging mental habits and easy long-established sequences.

I applaud sincerely. So far, though, the experiments just show us what we already knew: semantic anomalies produce N400 ERP effects; syntactic anomalies produce P600 ERP effects; and unfamiliar denominal verbs are syntactically anomalous but semantically coherent, so they produce P600s but not N400s.

I'm impressed that Davis has been inspired to study Shakespeare's language with the concepts and tools of cognitive neuroscience. And I'm especially impressed that his presentation of the issues, the experimental design, and the experimental results is clear and careful.

But I'm also disappointed that Davis hasn't tried to analyze Shakespeare's language linguistically -- that is, in terms of careful reasoning about about relations between form and meaning. He got as far as the concept of "'functional shift' or 'word class conversion'" -- noun into verb -- but that's the start of the analytic process, not the end. Back in 1979, Clark and Clark suggested a particular theory about how unfamiliar denominal verbs get their semantic coherence:

Our proposal is that their use is regulated by a convention: in using such a verb, the speaker means to denote the kind of state, event, or process that, he has good reason to believe, the listener can readily and uniquely compute on this occasion, on the basis of their mutual knowledge, in such a way that the parent noun (e.g. porch or Houdini) denotes one role in the state, event, or process, and the remaining surface arguments of the denominal verb denote others of its roles.

And Google Scholar knows about 115 later works citing Clark and Clark 1979. However, if Prof. Davis is like other literary scholars, the whole field of linguistics since 1950 or so is pretty much alien territory to him, and given the evidence of his interests and insights, that would be a shame.

Davis ends his article on a poetic note. Perhaps, he suggests,

Shakespeare’s art [is] no more and no less than the supreme example of a mobile, creative and adaptive human capacity, in deep relation between brain and language. It makes new combinations, creates new networks, with changed circuitry and added levels, layers and overlaps. And all the time it works like the cry of ‘action’ on a film-set, by sudden peaks of activity and excitement dramatically breaking through into consciousness. It makes for what William James said of mind in his Principles of Psychology, ‘a theatre of simultaneous possibilities’.

This is an attractive set of metaphors for a reader's response to literature. And MEG and fMRI experiments are underway, he tells us, so we can look forward to future results, some of which may indeed tell us something that we didn't already know about Shakespeare's writing or about his effect on us. Maybe Prof. Davis will be inspired by his neurolinguistic insights to venture into linguistic analysis itself. And along the way, maybe we'll learn why so many people are so annoyed by denominal verbs in contemporary English.

But experienced Language Log readers will know that there's another metaphorical film-set here, another theater of possibilities -- the arena of media reaction.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Act III: O O O O that Shakespeherian Rag—

'Are you alive, or not? Is there nothing in your head?'

But

O O O O that Shakespeherian Rag—

It's so elegant

So intelligent[T.S. Eliot, The Waste Land, lines 126-130]

The curtain opens, as convention dictates, on a press release: "Reading Shakespeare has dramatic effect on human brain", 12/18/2006. [There's a version with some pictures at "physorg.com".]

The first sentence is a real show-stopper:

Research at the University of Liverpool has found that Shakespearean language excites positive brain activity, adding further drama to the bard's plays and poetry.

What is this "positive brain activity"? The P600 event-related potential, which is routinely evoked by syntactic anomalies, whether dramatic and poetic or banal and prosaic. What's "positive" about it? The electrical polarity of the effect. Or rather, the direction of motion of the averaged ERP signal -- which as I understand the process, is the reverse of the polarity of the measured electric field, since "[t]raditionally, negative amplitudes are ... plotted upwards for EEG data".

The next few sentences of the press release maintain the dramatic intensity:

Shakespeare uses a linguistic technique known as functional shift that involves, for example using a noun to serve as a verb. Researchers found that this technique allows the brain to understand what a word means before it understands the function of the word within a sentence. This process causes a sudden peak in brain activity and forces the brain to work backwards in order to fully understand what Shakespeare is trying to say.

Of course, pretty much every English speaker uses this same technique -- though when usage experts notice, they tell us to stop. And the "technique" of verbing a noun doesn't speed up the understanding of meaning. On the contrary, it doubtless slows it down, relative to the processing of common words used in an ordinary way -- it just does this without triggering the N400 signature of semantic anomaly.

Also, it's misleading to say that "this process causes a sudden peak in brain activity". The "peaks" and "valleys" of ERP components are very small effects, about 1/4 the size of random variations in the EEG signal:

The brain response of a single event (i.e. the signal after the presentation of a single stimulus) is usually too weak to be detectable. The technique usually employed to cope with this problem is to average over many similar trials. The brain response following a certain stimulus in a certain task is assumed to be the same or at least very similar from trial to trial. That means the assumption is made that the brain response does not considerably change its timing or spatial distribution during the experiment. The data are therefore divided in time segments (or "bins") of a fixed length (e.g. one second) where the time point zero is defined as the onset of the stimulus, for example. These time segments can then be averaged together, either across all stimuli present in the study, or for sub-groups of stimuli that shall be compared to each other. Doing so, any random fluctuations will cancel each other out, since they might be positive in one segment, but negative in another. In contrast, any brain response time-locked to the presentation of the stimulus will add up constructively, and finally be visible in the average.

The noise level is typically about 20uV, and the signal of interest about 5uV. If the noise was completely random, to reduce the amplitude of the noise by a factor of n one would have to average across n*n samples. Averaging over 100 segments would therefore reduce the noise level to about 2uV, at least less than half the amplitude of the signal of interest. A further 100 segments (i.e. 200 segments altogether) would reduce the noise level to about 1.4uV.

You can critique the rest of the press release for yourself -- we're moving on to the good part, the media uptake. Here are some hyperlinked headlines, with associated quotes:

Shakespeare used advanced brain theories:

Reading Shakespeare excites the brain and could help stave off old age forgetfulness, research has shown.

The Elizabethan playwright took advantage of theories of brain consciousness to wow the audience in their heads as well as on stage, claim scientists.

Researchers from the University of Liverpool found the unconventional structure and words of Shakespeare's plays and poetry surprises the brain, which produces a sudden burst of activity, or excitement.

They claim it could help keep the brain healthy and lively.

Bard boosts brain, researchers say:

British researchers using modern medical technology have demonstrated what generations of teachers have told generations of students: Shakespeare is good for you.

Reading parts of Shakespeare's plays causes the brain to become positively excited, researchers from the University of Liverpool said in a release Monday.

Tis nobler in the mind to read Shakespeare:

Reading Shakespeare excites the brain in a way that keeps it “fit”, researchers say.

A team from the University of Liverpool is investigating whether wrestling with the innovative use of language could help to prevent dementia. Monitoring participants with brain-imaging equipment, they found that certain lines from Shakespeare and other great writers such as Chaucer and Wordsworth caused the brain to spark with electrical activity because of the unusual words or sentence structure.

Bard's wordgames 'spark mind activity':

READING Shakespeare can excite your brain with stimulating linguistic techniques, according to a new study.

Some school children may claim that reading the Bard's numerous plays and poems is fairly tedious, but researchers from the University of Wales, Bangor, and the University of Liverpool argue that though pupils may not realise it, their brains are becoming excited.

Shakespeare surprises our brains, study:

Shakespeare 'excites the brain':

Shakespeare's works are able to "surprise" the brain by using unexpected and exciting linguistic techniques, according to a new study. [...]

Professor Neil Roberts and Professor Philip Davis, together with Dr Guillaune Thierry from the University of Wales, Bangor, monitored brain responses in 20 people reading Shakespeare using a scanner called an electroencephalogram (EEG).

They found that a technique known as 'functional shift' – where, for example, a noun serves as a verb – allows the brain to understand what a word means before it understands the word's meaning in a sentence.

Literary experts and scientists have joined forces to investigate the effect Shakespearian syntax has on neural pathways. They have discovered that the brain reaches heightened levels of function thanks to the Bard’s unusually powerful use of words. Now more research is taking place to see if this increase in activity is acting as a work-out for the brain which could have lasting beneficial effects.

(Since it's surely a good thing for aging boomers to add daily doses of Shakespeare to their prophylactic intake of blueberries, red wine and fish oil, let's keep it quiet that they can get the same effect from reading about "dialoguing with stakeholders", or hearing about "the current favorites to podium at the Beijing Olympics" -- or for a mega-dose, from choral recitations of The Verbing Man.)

There seems to be something about the Christmas season that inspires the British media to follow a flack down the garden path in enthusing about the application of science to literary analysis. Last year we had the "common phrases used by [Agatha] Christie [which] acted as a trigger to raise levels of serotonin and endorphins, the chemical messengers in the brain that induce pleasure and satisfaction" ("The Agatha Christie Code: Stylometry, Serotonin and the Oscillation Overthruster", 12/26/2005; "The brave new world of computational neurolinguistics", 12/27/2005).

This year, it's that old Shakespearian P600.

Posted by Mark Liberman at December 26, 2006 07:37 PM