January 31, 2008

Nanoblahblah in The New Scientist

The latest issue of The New Scientist includes an article by Jim Giles entitled "Word nerds capture fleeting online English" (PDF here [Removed at the request of The New Scientist]). I'm quoted alongside such word buffs as Grant Barrett (of Double-Tongued Dictionary fame) and Mark Peters (Mr. Wordlustitude) on the subject of amateur lexicography in the digital age. The "amateur" versus "professional" dichotomy made in the article is a bit of an exaggeration, and it's certainly unfair to conflate carefully edited sites like Grant's and Mark's with the free-for-all of Urban Dictionary. (Grant, after all, has worked as a professional lexicographer, for instance in his capacity as project editor of the Historical Dictionary of American Slang.) Still, the article offers an enjoyable look at some of the fringe vocabulary lying outside the realm of traditional lexicography — often of the one-off variety catalogued on Wordlustitude, such as nanoblahblah, henchgoon, and celebufreak. (And for the record, I wrote on Language Log about Mark's "in-the-wild discoveries," not his "wild discoveries"! Wild, wacky stuff.)

[Update: Grant Barrett's take on the article is here.]

January 30, 2008

Olla Podrida

The New York Times contains a brief article entitled One Pot describing the Spanish dish known variously as cocido or olla podrida literally "rotten pot" According to the dictionary of the Real Academia Española, podrida may have an admiring connotation, similar to the use of "filthy rich" in English. Curiously, instead of the correct olla podrida, the article gives the name of the dish as olla poderida, which it explains as a derivative of poder "strength", because it gives you strength.

Reader Jim Gordon wondered about this and emailed the author of the article. Her response: she and her consultants and editors were aware of the correct name and etymology but thought that some readers might be put off by the notion of rotten food, so they changed the name a little and made up a fake etymology. It seems clear that they were not trying to deceive anyone with evil intent, but I am still taken aback that a respectable newspaper would make up a fake name and etymology.

I also wonder how many readers would really be put off by the use of the word "rotten" in the name of the dish, especially if informed that in this context it really means something like "really rich". If you think about it, we eat many foods that are "rotten". Some of them are, admittedly, rather exotic for most people. Here in Carrier country we have ʔʌk'undʒʌt "rotten fish eggs", which by other names is eaten by other native groups as well. To make it, you just let the eggs sit until they have a slippery feel and squeak a little when you rub them between your fingers. There is some risk in eating ʔʌk'undʒʌt because you never know which bacteria will take root. Now and then somebody gets sick or even dies from eating bad ʔʌk'undʒʌt.

Another "rotten" food from this part of the world is what in Carrier is called sleɣe (except in the Southwestern part of the territory, where it is called tl'inaɣe), in English usually just "grease". It is made from the eulachon fish Thaleicthys pacificus, an anadromous fish similar to smelt. Eulachon are also known as candlefish because they are so oily that when dried they can be lit like candles. I am partial to smoked eulachon. Grease is made by digging a pit, pouring in a lot of fish, and leaving them to rot for a couple of months. Then you pour in boiling water and skim off the oil that rises to the top. The oil is extremely nutritious and has just the right fatty acids. It is used as a condiment: people dip bread or dried fish into it. Grease is made by the coastal people who live along the rivers where the fish run, such as the Coast Tsimshian and Nisga'a, but for hundreds of years has been traded into the interior along the routes collectively known as "Grease Trails".

In China people eat pickled tofu 豆腐乳 made by air-drying cubes of bean curd under hay and then letting them ferment due to the action of airborne bacteria. I always have some in my pantry. A cube or two adds a nice flavour, somewhat like that of Limburger cheese, to fried rice. I don't think I've ever seen it in a restaurant, but it is often on the table in Chinese homes. Another "rotten" bean curd product is stinky tofu 臭豆腐, which is fermented in a kind of brine.

In Japan nattoo 納豆 is made by steaming soybeans and then fermenting them under the action of Bacillus subtilis natto.

There are some exotic "rotten" foods even in Europe. One Icelandic delicacy is hákarl, produced by burying a shark in the gravel for a few months in order to get rid of the uremic acid. I've never had this, but apparently even Icelanders consider the consumption of hákarl a sign of machismo, so it must be pretty bad. In the Faroe Islands they eat ræst kjøt, half dried mutton that is then allowed to rot, and ræstur fiskur rotten half dried fish. I am told that these too are an acquired taste.

In England pheasant is hung for some time to age before it is eaten. True connoisseurs reportedly hang it for several weeks, until the body separates from the head. This is the result of a combination of bacterial and enzymatic action.

It isn't necessary to look for exotic foods to find examples of "rotten" food. Sour cream is made from cream by the action of bacteria that produce lactic acid. This is also how most cheeses are made. Some cheeses are then allowed to rot after they are formed. This is how blue cheeses such as Roquefort, Stilton, and Gorgonzola, are made, as well as such soft cheeses as Camembert, Brie, Limburger, and my beloved Liederkranz, which is no longer made.

If you drink alcohol, you are consuming something "rotten". Most alcoholic beverages are produced by fermentation with yeast, a fungus. By the same token, you consume "rotten" food if you eat leavened bread. What makes bread rise is the growth of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The resulting alcohol is baked out, but the carbon dioxide generated as a waste product inflates the dough.

In fact, then, unless you are a strict vegan and teetotaler who never eats leavened bread, you almost certainly consume "rotten" foods.

Linguification is alive and well

I hate to break it to Geoff, but linguification ain't dead yet (at least, not as I understand the term). Earlier today on Morning Edition, Robert Smith commented on Rudy Giuliani's likely exit from the run for the Republican presidential nomination. (The following is from the audio of the story; the text is slightly different.)

It didn't take long before the crowd started to notice that Giuliani was speaking about his campaign in the past tense, and with a sense of nostalgia. "The responsiblity of leadership doesn't end with a single campaign. If you believe in a cause, it goes on, and you continue to fight for it, and we will."

For your convenience, I've highlighted the verbs in the Giuliani quotation. Any of them in the past tense?

By my count, there are four verbs in the present tense (The responsibility of leadership does, you believe, it goes, and you continue), one in the future tense (we will [continue to fight]), and two untensed (bare) verbs (to fight, doesn't end). The only reference in the quotation to the campaign being over (that is, in the past -- not the past tense) is the use of the verb end in the first sentence.

[ Update: Thanks to the folks (Arnold Zwicky being the first) who wrote to point out that I had mistakenly -- and in retrospect, quite stupidly -- classified end as a noun in my original post. I honestly don't know what came over me. Thanks also to everyone who noticed this and actively resisted commenting on it publically. I am grateful, but still guilty. ]

Does Smith (or the NPR production team) not know what a past tense is? Was there a longer quotation that they clipped such that it no longer included any verbs in the past tense, but then they forgot to go back and change the quotation's introduction? I doubt that either is true. It's just that linguification is too easy a trap to fall into -- and, probably, one that most folks wouldn't even pause to think about. Its use is metaphorical, clearly, and like some metaphors and unlike others, it's alive and well.

[ Comments? ]

January 29, 2008

"It appears to be an obscenity and we will be in touch"

According to Stephanie Farr and William Bender, "Fed up with jet noise, couple raise the roof" (Philadelphia Daily News, 1/24/2008):

According to Stephanie Farr and William Bender, "Fed up with jet noise, couple raise the roof" (Philadelphia Daily News, 1/24/2008):

Armed with white roof sealant and three choice words, a Ridley Township couple has bypassed bureaucracy and taken their grievances straight to the top - of their roof - in letters 7 feet tall:

"F_ck U F.A.A."

Mark Twain once said: "When angry, count to four, when very angry swear." Michael Hall said he tried the counting. He even counted past four to 20 - the number of times he said he called the Federal Aviation Administration's noise-complaint hotline. But each call, he said, was met with the same response - an automated message telling him the complaint mailbox was full and could no longer accept new calls.

Apparently the actual roof sign did omit the 'u', though it's hard to be sure from the coverage that I've seen so far. In any case, the photo on the right was photoshopped by the newspaper to remove the 'c' and the 'k'.

The best part of the story, for me at least, is the reaction of the Ridley Township manager:

Hall's mother, Anne, who lives two houses down from her son, wasn't as concerned with the picture of the plane as she was with her son's use of one of the most controversial and universal words in the English language.

"It is freedom of speech; I guess you can say what you want to say," she said.

But Anne E. Howanski, Ridley Township manager, isn't so sure Hall has the right to invoke that particular word on his own house, even if it isn't visible from the street.

"I will have to check our ordinance on this," she said. "It appears to be an obscenity and we will be in touch."

Courtesy of the internets, I was able to find the Ridley Township web page, which directs me in turn to www.e-codes.generalcode.com, which allows me to select "Township of Ridley, PA", turn on Fuzzy Logic, Root Word, Phonic and Natural Language (who knew?), and enter the search term "obscenity".

There's extensive discussion under Chapter 62, "adult uses", but this seems to target only "commercial exploitation" of various sorts, not complaints to federal agencies painted on rooftops and visible only from passing aircraft:

The Board of Commissioners find that the commercial exploitation of explicit sexual conduct through the sale, rental and showing of obscene films, videotapes, videodiscs, records, magazines, books, pamphlets, photographs, drawings and devices and the use of massage parlors and model studios for the purpose of lewdness, assignation or prostitution constitutes a debasement and distortion of a sensitive and key relationship of human existence, central to family life, community welfare and the development of human personality, is indecent and offensive to the senses and to public morals and interferes with the comfortable enjoyment of life and property, in that such interferes with the interest of the public in the quality of life and community environment, the tone of commerce in the Township, property values and public safety, and the continued operation of such facilities in a commercial manner is detrimental to the health, safety, convenience, good morals and general welfare of the Township of Ridley and of the residents, citizens, inhabitants and businesses thereof. Accordingly, the Board of Commissioners hereby declares such activities to be illegal as hereinafter set forth and, further, that such activities are hereby declared to be and constitute a public nuisance.

IANAL, but I think that the Halls are off the hook as far as Ridley Township obscenity ordinances are concerned. On the other hand, they might be in trouble on signage issues in general. Chapter 249 on "Signs and Billboards" defines a "sign" as

Any permanent or temporary structure, surface, fabric, device, or display or part thereof or any device attached, painted, or represented on a structure or other surface that displays or includes any letter, word, insignia, flag, or representation used as or in the nature of any advertisement, announcement, visual communication, direction, or is designed to attract the eye or bring the subject to the attention of the public.

and asserts that

No owner or occupier of any land, structure or building shall erect, alter, repair, enlarge remove or maintain any sign as defined herein within the Township of Ridley unless a sign license is obtained from the Township of Ridley.

Perhaps they could claim that the signage ordinance violates freedom of speech -- it does seem to prohibit standard political posters, for example -- and I guess there might be some question about whether riders in passing aircraft constitute "the public". But the Halls do seem to have succeeded in attracting the eyes of a certain number of people -- including, most likely, someone at the FAA. For all the good it will do them, alas.

[Update -- Tom McGrenery writes:

You've probably already had scads of emails about this, but the father of an acquaintance of mine once did something pretty similar in Wales some years ago... tired of low-flying RAF training runs, he painted "Piss off, Biggles" on his barn roof. (Story and photo here.)

It actually seemed to go down pretty well, particularly with the pilots, who ended up referring to 'Biggles' as a waypoint marker for their flights, but at least having the decency to fly higher over the farm.

Alas, the sign is apparently no longer there. More to the point, though, I wondered who or what "Biggles" is. And the Wikipedia tells me:

James Bigglesworth, better known in flying circles as "Biggles", is a fictional pilot and adventurer created by W. E. Johns.

He first appeared in the story "The White Fokker", published in the first issue of Popular Flying magazine, in 1932. The first collection of Biggles stories, The Camels are Coming, was published that same year.

]

[Chris Mackay, among others, has pointed out to me that Biggles features in a Monty Python skit, available here

Chris observes that there is an extensive discussion of the language/meta-language distinction at the beginning of the skit, deserving a post all its own.]

The world in a grain of sand

Andrew Gelman (at the Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference and Social Science blog) recently posted "A message for the graduate students out there"

Research is fun. Just about any problem has subtleties when you study it in depth (God is in every leaf of every tree), and it's so satisfying to abstract a generalizable method out of a solution to a particular problem.

which references a post of his from 2005:

In a recent article in the New York Review of Books, Freeman Dyson quotes Richard Feyman:

No problem is too small or too trivial if we really do something about it.

This reminds me of the saying, "God is in every leaf of every tree," which I think applies to statistics in that, whenever I work on any serious problem in a serious way, I find myself quickly thrust to the boundaries of what existing statistical methods can do.

That's certainly what happens in every area of linguistic research that I've ever worked on. Except that the terra incognita around us is not only methodological, but also descriptive and conceptual.

Andrew draws a cheerful -- and true -- conclusion, which also applies in the various areas of linguistics:

[This] is good news for statistical researchers, in that we can just try to work on interesting problems and the new theory/methods will be motivated as needed.

Last week at dinner after my talk at the University of Chicago, several of us were reminiscing about our grad-school experiences. John Goldsmith and I contributed a number of stories about Morris Halle, who taught this lesson so intensely and effectively.

As Andrew says, the initial effect of looking carefully at an arbitrary problem is generally additional complexity:

I could give a zillion examples of times when I've thought, hey, a simple logistic regression (or whatever) will do the trick, and before I know it, I realize that nothing off-the-shelf will work. Not that I can always come up with a clean solution (see here for something pretty messy). But that's the point--doing even a simple problem right is just about never simple.

Occasionally -- more often if you're smart or lucky -- you run across a simple problem for which the standard treatment is complicated and not very good, where you can find a better, simpler and generalizable solution.

It's commoner to find a better solution that's just as complicated, if not more so. But Morris taught us to have faith that if you keep at it, glimpses of the truth will be revealed.

One of my favorite examples comes from a rather different area of speech and language research. In the 1920s and 30s, Harvey Fletcher made basic discoveries about auditory physiology and the nature of speech perception, as a consequence of looking carefully at a mundane-seeming problem: how to predict the intelligibility of nonsense syllables as a function of the frequency response of a telephone circuit.

For an accessible and entertaining discussion, see Jont Allen, "Harvey Fletcher's role in the creation of communication acoustics", J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 99(4), 1996. And for an entirely different perspective on the "articulation index" research, see Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's fictionalized account (in The First Circle) of Gleb Nerzhin's doomed attempts to apply and extend the same ideas.

Yakonov wants Nerzhin to give up his work on the acoustics of perception, and to focus instead on hacking the circuitry of the vocoder that Stalin demanded to compete with SIGSALY, which Fletcher's group at Bell Labs had built during WW II (with the participation of Alan Turing on the British side).

More on misplaced spellings

I'm just a humble collector of Cupertino curiosities, but Thierry Fontenelle of the Microsoft Natural Language Group is deep in the orthographic trenches, tinkering with the algorithms used by the Microsoft Office spellchecker so that users get the spelling suggestions they deserve. (Whether they choose to take those suggestions is of course another matter.) Below is Thierry's response to my latest Cupertino foray, "Cupertino, Part Deux: I read it on misplace."

Ben Zimmer’s recent post on “MySpace”, “Misplace” and spell-checkers is very interesting. As noted in his post, the word MySpace is now in the lexicon of the Office 2007 spellchecker. I guess nobody will complain about that addition (that shows that the tools evolve as well, like our vocabulary, and solving the Cupertino issues he regularly describes on Language Log is an algorithmic problem, but also a problem related to the coverage of the dictionary).

As you know, a spell-checker has two main functions: it should spot mistakes, but it should also try to suggest the most likely word form to replace the erroneous input. Computing the suggestions is usually an algorithmic process based upon the concept of “edit distance”, which measures the number of character manipulations that were necessary to turn a correct word into an incorrectly spelled one: deleting, adding, transposing or replacing a character are the most common manipulations. Here are examples of such manipulations (the word to the right of the arrow is flagged with a red squiggle):

Deleting a character: information → infomation Adding a character: developing → developping Transposing 2 characters: believe → beleive Substitution: independent → independant

When a word is not found in the speller dictionary, the speller tries to find the nearest candidate in terms of edit distance. This algorithmic process is used to compute the order of the suggestions. In addition to “edit distance”, which is a general, language-independent concept, some language-specific knowledge may also be used to fine-tune the order of suggestions. There can be a specific rule saying for instance that some users have problems with the letters “gh” which they sometimes mix up with “f”: if you write “rouf”, you will therefore see that the application of the edit distance mechanism is responsible for the suggestion “roof” appearing in the first position, but you will also see “rough” in the list of suggestions offered by the speller, even though, in terms of edit distance, there are more manipulations to delete “gh” and add “f”: this is based upon an English-specific typology of errors which enables us to take into account frequent mistakes.

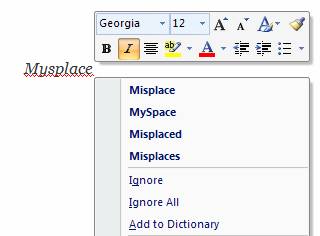

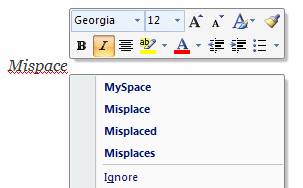

Ben cites one of his readers who points out that the latest Word spellchecker gives misplace as the first suggestion for Mysplace. That is true and is in fact expected, since going from Misplace to Mysplace is done by substituting the “i” and the “y” (one-character change only).

The distance is longer to transform MySpace into Mysplace (turning the capital “S” into a lower-case “s” and adding “l”). This is why MySpace appears as the 2nd suggestion.

Note that MySpace is listed as the first suggestion when you type Mispace in Office 2007, and not as the second one, as suggested by Ben’s reader (see screenshot below):

Of course, it will always be up to the writer to decide whether they really meant MySpace or something else. In any case, I don’t think this is a “Cupertino” issue, since there is no automatic replacement (as you know, the Cupertino issue affected the Word speller in the 1997 version, over 10 years ago, and was due to the AutoReplace function – many things have changed since then and the Office proofing tools have improved a lot, for instance with the introduction in Office 2007 of a contextual speller). The speller does its job when it flags the mistake in Mispace and also does its job when it suggests the most likely corrections. I would argue that if the user unfortunately clicks on “Misplace” in this list when they meant “MySpace” and had written “Mispace”, the tool cannot really be blamed, can it? ;-).

[guest post by Thierry Fontenelle, Microsoft Natural Language Group]

Shake, rattle and roll

It is extremely common to find non-linguists espousing a kind of naive semanticism about syntax: they think everything about syntax springs from meaning, i.e., that where you can use a certain word just follows in an obvious way from what that word means. There are plenty of cases that I take to be clear counterexamples; for example, one pointed out by Richard Hudson of University College London in the 1970s is that likely seems to mean exactly what probable means, and in many contexts they are interchangeable, but I'm likely to be late is grammatical while *I'm probable to be late is not. But the layperson is often not easy to convince: they just assert that the latter sounds bad because "it doesn't mean anything" (which of course was supposed to be the datum, not the explanation!). It may be that you simply agree with them.

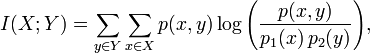

When reflecting on this I have often thought about the case of verbs expressing sharp or erratic movements. Deirdre Wilson (also of UCL) pointed out to me a long time ago that shaking and quaking are basically exactly the same thing — if it quaked then it shook, and conversely — but one is transitive (takes a direct object) and the other is not (Try shaking it is grammatical but *Try quaking it isn't). Below is a list of fifty verbs of shaking, rattling, rolling, juddering, twitching, jerking, oscillating, lurching, and similar movements. The question I put before you is simply whether you could truly have told in advance from knowing the semantic facts — what it means for something to shake, rattle, roll, judder, twitch, etc. — whether each of these verbs would be transitive or not. A plus sign in the intransitive column for shake means I think that It shook is clearly grammatical, and a plus sign in the transitive column means I think that Someone shook it is clearly grammatical. The intransitive mark for jog is for The road jogs left at the end of that block, and the transitive one is for You jogged my elbow. Flutter is shown as transitive because you can flutter your eyelashes. And so on. I'm sure I have missed some cases; the tabulation below is based on a quick rough-and-ready assessment, not detailed corpus searching (that is perhaps a task for the future). But see what you think. Could you predict the verbs that can take a direct object, just from the sense? Because if not, naive semanticism is wrong, and linguists' almost universal belief that meaning does not predict all syntactic properties is justified.

| Intransitive | Transitive | |

| agitate | + | |

| bob | + | |

| bounce | + | + |

| brandish | + | |

| bump | + | + |

| convulse | + | + |

| flap | + | + |

| flicker | + | |

| fluctuate | + | |

| flutter | + | + |

| jar | + | |

| jerk | + | + |

| jiggle | + | + |

| jog | + | + |

| joggle | + | + |

| jolt | + | + |

| jostle | + | |

| judder | + | |

| jump | + | + |

| leap | + | |

| lurch | + | |

| oscillate | + | + |

| palpitate | + | + |

| pulse | + | |

| quake | + | |

| quaver | + | |

| quiver | + | |

| rattle | + | + |

| roll | + | + |

| shake | + | + |

| shimmy | + | |

| shiver | + | |

| shudder | + | |

| spring | + | |

| swing | + | + |

| teeter | + | |

| throb | + | |

| tremble | + | |

| twitch | + | + |

| veer | + | |

| vibrate | + | + |

| wag | + | + |

| waggle | + | + |

| wander | + | |

| wave | + | + |

| waver | + | |

| wiggle | + | + |

| wobble | + | + |

| wriggle | + | |

| zigzag | + |

[Update for specialists: I am not unaware of semantic distinctions like that between internal and external causation, which do have some influence on the possibility of transitive uses (see Beth Levin and Malka Rappaport Hovav, Unaccusativity (MIT Press, 1995), pp. 90ff). I am not suggesting that my own position is (to use a term that Andew Koontz-Garboden mischievously suggested) naive syntacticism. I'm just saying this is going to be some complex function of both syntax and semantics.]

Racial abuse not cricket (and vice versa)

The Harbhajan Singh story is surely a free-speech dispute that holds almost no satisfaction for anybody. American readers may not have heard about it, because it concerns (a) India, (b) Australia, and (c) cricket. For Americans who are not international news junkies, the quantity of news encountered about any of these three topics in a week will typically amount to zero. Harbhajan Singh is a spin bowler (the analog of a pitcher in baseball) who plays on the Indian national team. Andrew Symonds is a member of the Australian cricket team, a batsman from Queensland. Symonds is black (not because of Australian Aboriginal heritage, incidentally, but because one of his birth parents was West Indian; he was adopted by English parents who moved to Australia when he was a baby). During an argument on the pitch during a test match (a major international game), Harbhajan is alleged to have called Symonds a "big monkey".

When the Australian captain complained, charges were immediately brought under international cricketing regulations, since they forbid use of language which "offends, insults, humiliates, intimidates, threatens, disparages or vilifies another person on the basis of that person's race, religion, gender, colour, descent or national or ethnic origin." Harbhajan was found guilty, and barred from playing for three games. India immediately threatened to pull its team out of the series and go home. Harbhajan appealed, and a New Zealand judge, John Hansen, was appointed by the International Cricket Council as an appeals commissioner to hear the appeal in Adelaide's Federal court. He announced his decision yesterday: the charge is downgraded to one of using abusive language, and Harbhajan has been fined 50 per cent of his match fee, but can continue playing. No racism, no continuing dispute, and cricket can go on. Everything is peachy. Unless of course you care about any of the underlying issues.

First Amendment radicals will be disturbed that the charge should never have been brought. People should be free to speak their minds in their own ways. On a sports field tempers will run high, and those who have racist tendencies will reveal themselves by using racist language (if we assume that is what "monkey" is), and they will forfeit the respect of those of us who despise racism.

Those who favor regulations and laws to control racist speech will find it a scandal that Harbhajan basically escaped the original charge. Symonds is said to have suffered racial abuse before, at three cricket grounds in India in October 2007 (see Wikipedia); this is becoming a pattern.

India fans will insist that there is no evidence that Harbhajan did anything at all; otherwise such evidence would have been presented. The microphone that the Nine Network had placed near the batsman's area did not pick up the insult (though what it did pick up was pretty damning: see the transcript here, and note that Harbhajan does not attempt to deny what he's being accused of). So it is an outrage, they will say, that he was fined a large sum of money for an angry word that no one can prove he uttered.

Australia fans will be disgusted that what really appears to have been operative here was (surprise, surprise) money. India is now the biggest financial powerhouse in the cricket world: there is simply more money to be made by televising cricket for the billion-strong population of India than for anything else on earth. The Australian market is trivial by comparison. For India to pack up its gear and go home would have been a financial disaster for world cricket. So what the business side of the cricket industry really needed was for Harbhajan to be cleared of any alleged simian conversational references so that business could continue, never mind what he had done. And that is what has just occurred. Play on.

A nasty judgment call, I think, for anyone with radical free-speech inclinations who also cares about sport. On the one hand, in a free society you should be free to call an opponent a monkey in a disputewithout ending up in the High Court, if you want to sink that low rhetorically. (According to this cricket blog the India captain Chetan Chauhan agrees that Harbhajan said "monkey", but that in India that's not an insult. I don't know about that; but when Ravana called Nandi a monkey in Indian mythology, Ravana was then cursed for it.) But on the other hand, sport is increasingly being disrupted by racism: British soccer fans, in particular, used to be notorious for appalling racist abuse of black players. Soccer followers tell me that in England the problems (crowds of young men booing and gibbering and shouting abuse and jump up and down scratching their armpits when an African player on the other side takes the field) have largely abated in the last few years; but on the continent of Europe, in Spain particularly, there are still reports of racist fan behavior; and buses in Edinburgh still carry posters inside warning people that they can be placed on a police list of people banned from attending any soccer game for periods of many years if they engage in racist abuse.

Free speech for all? Or safe and sane working conditions for hard-working African sportsmen? There is a basic clash here between freedom of expression and reasonable standards of public behavior. It certainly is not a simple open-and-shut issue.

One little further linguistic point: as I wrote about India's new financial muscle above, naturally the metaphor of the 800-pound gorilla in the old joke ("Where does he sleep? Anywhere he wants!") occurred to me as a vivid way to talk about the undeniable force India has become; but then I suddenly saw that in the context a gorilla metaphor might not be the right figure of speech to choose...

[Update: Vinay P. Jain has told me an extremely interesting fact. It turns out that there is some doubt about what language the insult was delivered in. It is thought that Harbhajan (who is from Delhi, and thus speaks Hindi) may have uttered the widespread north Indian abusive phrase तेरी माँ की (terii mãã kii), literally "your mother 's" — an almost exact equivalent of the familiar American you mama!. (Your mother's what? It is left unspecified lest the insult become too extreme.) The combination of the noun mãã "mother" (in which the tildes over the long vowel [aa] denotes nasalization) and the genitive postposition kii sounds extremely similar to the English word monkey. So Harbhajan may have just been muttering the equivalent of "yo mama!" to Symonds, mainly for the benefit of his (Hindi-speaking) team-mates. In which case the judge was right, this was abuse, but not racist abuse. On the other hand, some discussion in the press has cast doubt on the Hindi story; for one thing, there is video of cricket fans actually calling Symonds a monkey in India a few months ago in terms that left no doubt about it. Then again, one of my Australian correspondents points out that there has long been concern about the abusive language used on the pitch by the Australian team. Michael Jeffery, the Governor-General of Australia (i.e., the Queen's representative in the country, of which she is still the official head of state) has commented on his perception of graceless behavior of Australian cricketers. (And there are certainly some tales to tell; you can read one or two here.) The Australians are not blameless. Things are always more complicated than one at first thinks, aren't they?]

January 28, 2008

"Love" as an Act of Hostility

[This is a guest post by Jane Acheson]

Geoffrey K. Pullum's post the other day ("Yale Sluts and Princeton Philosophers" , 1/23/2008) ham-handedly tried to assert that calling women sluts, while potentially insulting, could not possibly amount to sexual harassment:

Insane over-interpretation of laws against such things as "hate speech", sexually harassing speech, and defamation will not be disappearing any time soon, it seems.

The context is as follows: a photo appeared on Facebook, of a group of Zeta Psi pledges with a poster saying WE LOVE YALE SLUTS posed in front of the Yale Women's center. Pullum is convinced that the reaction within the Yale community, which involved threat of lawsuit, a brouhaha, and instant contrition on the part of the men involved, could not have sprung from sane, serious law, and must be the result of some kind of legal hysteria. But that "insane over-interpretation" is actually just a straight-up, legally-recognized form of sexual harassment, according to the applicable policies of Yale, the state of Connecticut, and federal law. It is called "hostile environment," and Yale's policy (PDF) describes it thusly:

"Hostile environment" harassment is unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature that creates an intimidating, hostile or offensive working or academic environment and has the purpose or effect of substantially interfering with the victim's work or study. Hostile environment sexual harassment can include sexual advances, repeated taunts regarding sexual preferences, taunting jokes directed at a person or persons by reason of their sex, obscene posters with sexual connotations and sexual favoritism in work assignments.

If "slut" is a term of abuse -- a taunt -- directed at women for reasons of their sex, then the incident in question appears to be pretty straightforward sexual harassment. Is "slut" a term of abuse? Try calling a female colleague a slut, and the black eye you get back will be your proof. Is it directed at women purely because they're female? In this case, the taunt was directed so generally that the perpetrators, a group of frat pledges, took their WE LOVE YALE SLUTS poster across campus and posed with it in front of the Yale Women's Center. They couldn't be bothered to taunt a specific woman on the campus; or even a specific group of women, like a sorority counterpart: they taunted all the women of Yale.

These frat pledges may not understand themselves to be participating in a social pattern of hostility and intimidation; indeed, Pullum's defense of their speech rests in part on his certainty that the men were expressing adoration of, and idealized (likely vain) wishing to obtain, the women of Yale. And I'll agree: I'm sure those frat pledges think they love women. They love women as receptacles for sexual mythology, as things to conquer or obtain or enjoy, and not as people.

WE LOVE YALE SLUTS. As Livejournal blogger Cija opined sarcastically: "There can't be anything wrong with an affirmation of a man's love, can there? Come on, sluts, accept my love."

That's what we're talking about here, isn't it? "Love" as a thinly-disguised codeword for "fuck". Name-calling meant to reduce all women to sexual targets. A photograph posted on Facebook as a trophy of the frat boys' "triumph" over the dignity and safe space of the Yale Women's Center. Posters and patterns of public behavior intended to squash the variety and vibrancy of half the human species into a male-defined fantasy object of constant sexual availability.

Sounds pretty hostile to me. Should women have to endure worse behavior in their work and study settings than men, simply because of their sex? The law says they shouldn't. If that's insane, then go ahead and call me crazy.

[Above is a guest post by Jane Acheson.

Note that while Jane was composing her reply, Geoff added an update to his post that brings his position closer to hers.

A bit more about the context, from the Yale Daily News (Zachary Abrahamson, "Misogyny claim leveled at frat", 1/22/2008):

Former Women's Center Public Relations Coordinator Jessica Svendsen '09 said she found a group of men chanting "Dick! Dick! Dick!" in front of the Elm Street entrance to the Center, which is located in Durfee Hall, shortly before midnight last Tuesday. Frightened, she decided to take a detour through the Center's Old Campus entrance, she said.

"I stopped even before I got to Durfee, because I recognized that as a single woman facing 20 to 25 frat boys, I wasn't going to be able to enter the Women's Center," Svendsen said. "This was my first experience knowing that misogyny does happen at Yale -- and right in front of the Women's Center door."

The photo appeared on Facebook the next day.

Other sources claim that the Zeta Psi pledges were actually chanting "DKE! DKE!" (pronounced "deek"), the name of another fraternity, perhaps in an attempt to shift the blame for the action. Whatever they actually did, it's worth observing that these pledges were almost certain being hazed, i.e. performing a demeaning or dangerous task specifically assigned by the full members of the frat they were trying to join.

The EEOC's page on sexual harrassment is here. ]

January 26, 2008

Linguistic Incompetence at the FCC

The Federal Communications Commission is proposing to fine ABC $1.4 million for airing in 2003 between 6 a.m. and 10 p.m. an NYPD Blue episode showing a woman's buttocks. The details are in this Notice of Apparent Liability for Forfeiture¹. According to the FCC, the episode violated its decency regulations because it depicts "sexual or excretory organs or activities". In response to ABC's argument that the buttocks are not a sexual organ, the ruling states:

Although ABC argues, without citing any authority, that the buttocks are not a sexual organ, we reject this argument, which runs counter to both case law²³ and common sense.

This is the entirety of the FCC's discussion of this point.

I am shocked that the FCC has erred on such a simple linguistic point.² The buttocks are not used for sexual reproduction so they are not a sexual organ. Indeed, they are not an organ of any sort, which is defined by Wordnet as: "a fully differentiated structural and functional unit in an animal that is specialized for some particular function". Unlike the heart or the kidneys, the buttocks are not "specialized for some particular function".

The FCC's claim that case law shows that the butocks are, for legal purposes, a "sexual organ", is contained in footnote 23:

²³ See, e.g., City of Erie v. Pap’s A.M., 529 U.S. 277 (2000) (Supreme Court did not disturb a city’s indecency ordinance prohibiting public nudity, where the buttocks was listed among other sexual organs/body parts subject to the ordinance’s ban on nudity); Loce v. Time Warner Entertainment Advance/Newhouse Partnership, 191 F.3d 256, 269 (2d. Cir. 1999) (upholding state district court’s determination that Time Warner’s decision to not transmit certain cable programming that it reasonably believed indecent (some of which included “close-up shots of unclothed breasts and buttocks”) did not run afoul of the Constitution).

The two cases cited merely establish that the display of the buttocks may be considered indecent. In both cases, the buttocks are included in lists of body parts whose display is prohibited, but nothing in either case justifies the equation of the set of prohibited body parts with the sexual organs. Indeed, one can make the opposite argument. The relevant City of Erie ordinance is Ordinance 75-1994, codified as Article 711 of the Codified Ordinances of the city of Erie (cited in the opinion of the Supreme Court above). It includes the definition:

"Nudity" means the showing of the human male or female genital [sic], pubic hair or buttocks …

The ordinance lists the buttocks in addition to the genitalia, which is to say, the reproductive organs. This would be quite unnecessary if the buttocks were reproductive organs.

The problem for the FCC is that it wants to enforce a broad notion of indecency that includes display of the buttocks but that its own regulations contain a narrower definition. Both in its ruling generally and in its mis-citation of the case law in footnote 23, the FCC appears to believe that it can expand the definition of indecency from what it is to what it would like it to be by fiat.

I trust that the courts will overturn this idiotic ruling if it does not die of embarrassment first.

¹ Linguistic analysis at the FCC may be lacking, but somebody there has taste in machine names. The server on which this document is located is called hraunfoss, the name of one of Iceland's many scenic waterfalls. This set of photographs of waterfalls by Icelandic photographer Thomas Skov includes a nice photograph of Hraunfoss.

² Do you think that the FCC has been taken over by some of those Hispanic immigrants that we so often hear about, the ones that refuse to learn English? ¡Comisionados! ¿Pensan ustedes que las nalgas sean órganos sexuales? Según la Wikipedia: "Los órganos sexuales son las estructuras especializadas para la formación de los gametos o células reproductoras." Pienso que no incluyan las nalgas.

The media gap

In the latest New York Review of Books, Sarah Boxer ("Blogs", NYRB 55(2) 2/14/2008) reviews ten spectacularly, um, diverse books. There's Cass Sunstein's Republic.com 2.0 and Hugh Hewitt's Blog: Understanding the Information Reformation That's Changing Your World. There's Andrew Keen's The Cult of the Amateur: How Today's Internet Is Killing Our Culture and Daniel Solove's The Future of Reputation: Gossip, Rumor, and Privacy on the Internet. There's ... well, you get the idea.

After some preliminary lexicography -- perhaps there are NYRB readers who don't know what those "blog" things actually are --Boxer disposes of her ten books in one sentence, and gets to the question she really wants to explore:

A growing stack of books has pondered the effects of blogs and bloggers on culture (We've Got Blog and Against the Machine), on democracy (Republic .com 2.0), on politics (Blogwars), on privacy (The Future of Reputation), on media (Blog: Understanding the Information Reformation and We're All Journalists Now), on professionalism (The Cult of the Amateur), on business (Naked Conversations), and on all of the above (Blog!). But what about the effect of blogs on language?

Are they a new literary genre? Do they have their own conceits, forms, and rules? Do they have an essence?

Since none of the ten books being reviewed engages this question, she naturally turns to Language Log:

Bloggers assume that if you're reading them, you're one of their friends, or at least in on the gossip, the joke, or the names they drop. They often begin their posts mid-thought or mid-rant—in medias craze. They don't care if they leave you in the dust. They're not responsible for your education. Bloggers, as Mark Liberman, one of the founders of the blog called Language Log, once noted, are like Plato. :-) The unspoken message is: Hey, I'm here talking with my buddies. Keep up with me or don't. It's up to you. Here is the beginning of Plato's Republic:

I went down yesterday to the Peiraeus with Glaucon, the son of Ariston, to pay my devotions to the Goddess, and also because I wished to see how they would conduct the festival since this was its inauguration.

Wait a second! Who is Ariston? What Goddess? What festival?

And here, for comparison's sake, is a passage from Julia {Here Be Hippogriffs}, a blog about motherhood and infertility:

Having left Steve to his own devices for the past three days I am being heavily pressured to abandon the internet (you! he wants me to abandon you!) and come downstairs to watch SG-1 with him....

So this will have to be quick. Vite! Aprisa aprisa!

I went to Blogher. It was rather fun and rather ridiculous and I am quite glad I went although I do not know if I would ever go again. One thing of note for my infertile blogging friends: DO NOT EVEN THINK ABOUT IT. Do not go. Do not ever ever go to Blogher.

Huh? Who's Steve? What's Blogher? A blog? (No.) A mothers' club? (No.) A blogging conference? (Yes.)

(The LL link is "Weblogs were invented by... Plato!", 11/3/2003.)

After a couple of thousand interesting words about blogging styles, Boxer brackets the discussion with another LL reference:

Writing like this might seem easy, but just try it. Geoffrey Nunberg, a linguist at Stanford who writes for newspapers and radio and sometimes contributes to the blog Language Log, admitted on NPR back in 2004, "I don't quite have the hang of the form." And, he added, many journalists who get called upon by their editors to keep blogs are similarly stumped: "They fashion engaging ledes, they develop their arguments methodically, they give context and background, and tack helpful IDs onto the names they introduce." Guess what? They read like journalists, not bloggers.

(The link is "Blogging in the global lunchroom", commentary broadcast on "Fresh Air," 4/20/2004.)

Vanity aside, Boxer's article is entertaining and intelligent and funny. But there's one aspect of the situation that she misses, something that's always puzzled me: a sort of "media gap". There's not much "virtual click-through", so to speak, from traditional media to the web; and perhaps as a result, there's often a lot less commentary back the other way than you might expect.

Over the years, Language Log has been mentioned or even featured from time to time in fairly high-traffic places. When the source is a web site of some sort, I see a bump in our readership -- but the effect is much smaller, in proportion, when readers need to do anything beyond clicking on a link in order to find us. And exposure on broadcast media, such as Geoff Nunberg's pieces on "Fresh Air", has barely any effect at all. (For an example of the click-through effect, see "The Gray Lady goes up against fark.com", 6/20/2006.)

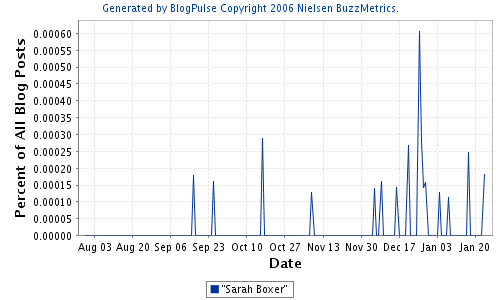

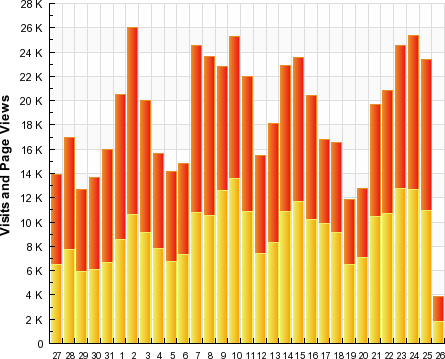

Although the NYRB has a paid circulation of around 140,000 -- and some online readership as well -- Boxer's mentions of LL haven't had any detectable effect on our visit and hit counts:

Nor has her NYRB article gotten much uptake so far elsewhere in the blogosphere:

Blogpulse has registered two reactions so far, on Jan. 24 and 25. (And one more that doesn't mention the author's name.)The peak in the Blogpulse graph just after Christmas represents two posts (counted by Blogpulse as four) noting that NPR's Morning Edition had a story featuring selections from Boxer's new book Ultimate Blogs: Masterworks from the Wild Web. According to Wikipedia, Arbitron estimates that 13 million people listen to Morning Edition every week. It's "the second most-listened-to national radio show, after The Rush Limbaugh Show". Millions of people, and thousands of bloggers, must have heard that segment -- but only two bloggers linked to it.

I'm not sure what this media gap means, beyond the obvious: the more memory and effort that goes into following up on a reference, the less likely people are to do it. But this is surely part of the reason for the success of new media (including, obviously, open-access scholarly and scientific publishing). Is it also part of the reason for the decline of the old?

[Update -- Ben Zimmer writes:

Just thought I should mention that Sarah Boxer solicited a few of my Language Log posts for her forthcoming blog anthology, Ultimate Blogs, on the topics of truthiness, diapers, Googlefreude, and Chinese menus. I haven't seen it yet (the publication date is Feb. 12), but Publishers Weekly said my contributions make Language Log read like "a wonderfully expansive and more self-aware William Safire column."

]

January 25, 2008

Political Correctness and the Use/Mention Distinction

Professor Donald Hindley was recently found guilty of racial harassment by Brandeis University for statements that he made in his Fall 2007 Latin American Studies course. The case is discussed in this report by the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, and in a number of blog posts, including this one by Margaret Soltan and this one by Eugene Volokh. Criticism of Brandeis is based in part on what appears to have been an egregiously unfair process, and in part on the nature of the charges against him.

Brandeis has apparently refused to disclose publicly exactly what Hindley said that it considers "racial harassment"¹, but according to FIRE, which in my experience has a record of accuracy in such matters, the complaint is that he said:

Mexican migrants in the United States are sometimes referred to pejoratively as 'wetbacks'.

His offense is described as having used the word 'wetback'. This is false. He did not use the word 'wetback'; he mentioned it. That is, he did not choose the word 'wetback' for his own communicative purposes. Rather, he referred to its use by others. This is not a mere distinction of terminology: there is a vast difference between the two. When someone uses a word, he or she is responsible for what it conveys, but when one mentions a word, one assumes no such responsibility.

If someone says "The only good Indian is a dead Indian", he or she has asserted a proposition with which other people are entitled to take issue, and one can validly infer that the speaker does not like Indians. If, however, someone says "General Sheridan said: 'The only good Indian is a dead Indian'", the only proposition asserted is that General Sheridan said a certain thing. Nothing is asserted about Indians, and in the absence of additional information, no valid inference can be drawn regarding the speaker's attitude toward Indians. There is no way to tell whether the speaker agrees with General Sheridan or disagrees with him.

Speaking generally:

In the absence of other information, one is not entitled to draw any inference as to the speaker's attitudes and beliefs from mentions.

The use-mention distinction is not some recent and esoteric discovery known only to linguists - it is an old idea, well known to philosophers, one that should be familiar to anyone to whom it falls to interpret language. Nonetheless, failure to recognize it is distressingly common. A prominent incident in which a speaker was improperly condemned for a mention was the speech that the Pope gave at Regensburg, in which he quoted a statement by the Byzantine Emperor Manuel II about Islam. You can read the full text of his speech, in the original German, on the Vatican web site here. The Vatican has an English version here.

The Pope's speech is a subtle and academic discussion of the relationship between faith and reason. At one point, he discusses a series of conversations that took place circa 1391 between the Byzantine Emperor Manuel II Paleologus and "an educated Persian". He then draws attention to a portion of one conversation. I will quote him at length so as to provide the full context.

The emperor must have known that surah 2, 256 reads: "There is no compulsion in religion". According to the experts, this is one of the suras of the early period, when Mohammed was still powerless and under threat. But naturally the emperor also knew the instructions, developed later and recorded in the Qur'an, concerning holy war. Without descending to details, such as the difference in treatment accorded to those who have the "Book" and the "infidels", he addresses his interlocutor with a startling brusqueness on the central question about the relationship between religion and violence in general, saying: "Show me just what Mohammed brought that was new, and there you will find things only evil and inhuman, such as his command to spread by the sword the faith he preached". The emperor, after having expressed himself so forcefully, goes on to explain in detail the reasons why spreading the faith through violence is something unreasonable. Violence is incompatible with the nature of God and the nature of the soul. "God", he says, "is not pleased by blood - and not acting reasonably - is contrary to God's nature. Faith is born of the soul, not the body. Whoever would lead someone to faith needs the ability to speak well and to reason properly, without violence and threats... To convince a reasonable soul, one does not need a strong arm, or weapons of any kind, or any other means of threatening a person with death...".

The decisive statement in this argument against violent conversion is this: not to act in accordance with reason is contrary to God's nature. The editor, Theodore Khoury, observes: For the emperor, as a Byzantine shaped by Greek philosophy, this statement is self-evident. But for Muslim teaching, God is absolutely transcendent. His will is not bound up with any of our categories, even that of rationality. Here Khoury quotes a work of the noted French Islamist R. Arnaldez, who points out that Ibn Hazn went so far as to state that God is not bound even by his own word, and that nothing would oblige him to reveal the truth to us. Were it God's will, we would even have to practise idolatry.

At this point, as far as understanding of God and thus the concrete practice of religion is concerned, we are faced with an unavoidable dilemma. Is the conviction that acting unreasonably contradicts God's nature merely a Greek idea, or is it always and intrinsically true? I believe that here we can see the profound harmony between what is Greek in the best sense of the word and the biblical understanding of faith in God.

If you read carefully, the Pope nowhere endorses the Emperor's characterization of Islam. The closest he comes is to mention briefly what the Emperor must have known. Moreover, he describes the Emperor as addressing his interlocuter "with startling brusqueness", which suggests that he has no intention of baiting Muslims himself. What he picks up on is the theme of the Emperor's critique of what he (that is, the Emperor) took to be the Muslim view, namely that faith is bound up with reason. The Pope briefly contrasts Catholic and Muslim views of the role of reason, and then carries on with a more general discussion of the relationship between faith and reason that has nothing in particular to do with Islam.

In sum, whatever the correct view of the Muslim stance (or stances) on forcible conversion and jihad may be, the Pope actually took no position on the question. He merely used an argument made by the Emperor Manuel II against what he took the Muslim position to be as the basis for his own discussion of faith and reason. Having made no assertion about forcible conversion in Islam, the Pope is immune to criticism on these grounds and owes no one an apology.

This is not to say that there are no circumstances in which a mention may be improper. In some circumstances, bringing up a certain topic will be hurtful to someone, regardless of what one has to say about it. Similarly, some people may in some circumstances be hurt or offended by certain words. Some people, for example are upset even by seeing the word "fuck" in a context such as this, where it is not used to communicate anything at all. It may be, therefore, that there are situations in which we should condemn mentions as well as uses.

It is nonetheless important to distinguish between offensive uses and offensive mentions, for two reasons. First, while there are arguably no circumstances in which some offensive uses are acceptable, there are many socially valuable situations in which offensive things must be mentioned. Surely it is not wrong to explain to a foreigner who has learned the word from a book or a child who has overheard it that "nigger" is not an acceptable way to refer to black people, yet this may be difficult or impossible without mentioning the offending word. Teachers must be able to assign and discuss texts containing offensive expressions. Scholars must be able to discuss historical usage and the way it has changed, or why a term is offensive.

Second, while it is generally straightforward to determine that a use is intentionally offensive, it is much harder to determine whether a mention is intentionally offensive. When someone asserts that the only good Indian is a dead Indian, it is clear that he or she hates Indians and fair to condemn the statement. When someone merely quotes such a statement, a process of inference is required to determine his or her intention. Occasionally, the inference may be certain, as when the speaker adds "and I agree", but more often the inference will be uncertain or even impossible. If mentions are conflated with uses, there is a serious risk of condemning innocent people.

In sum, failure to distinguish between uses and mentions poses a danger to freedom of speech and rational enquiry as well as the danger of falsely accusing and condemning innocent people.

¹ The idea that "people who enter the United States illegally by crossing the Rio Grande" constitute a race is of course absurd. Indeed, negative attitudes toward 'wetbacks' are not necessarily even ethnically-based. Such attitudes may be class-based, since it is mostly poor people who enter illegally, or they may be based on disapproval of illegal immigration.

Cupertino, Part Deux: I read it on misplace

Continuing the Cupertino theme... Michael Covarrubias and Mike Pope both noted a fine example of spellchecker miscorrection from the Associated Press last week. As the AP reports, a Washington State trooper made the unorthodox decision of putting Oregon plates on his unmarked car in order to catch a speeder unawares:

That's how the article continues to appear on the AP's own website, as well as on hosted versions from Google News, Yahoo News, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the Boston Globe, and many other news sites. As the two Michaels observe, this appears to be a case of a spellchecker unable to recognize Myspace, or at least a misspelled version of it. Covarrubias writes:

It looks like a clear example of the Cupertino effect turning myspace into misplace. But most spell checkers are pretty good at recognizing conjoined words. And the only suggestions I get for "myspace" are "my space" and "MySpace". So the networking

sightsite has made it into the Word 2007 spell check dictionary.

Where did 'misplace' come from? Perhaps the writer put an <l> in there: 'mysplace'. 'Place' seems like a much more common string than 'pace' so a slip like that makes sense. Especially if the writer's ear was contaminated by the old line: 'my place or yours?'

But no one really says that anymore do they?

If misplace is indeed the result of misspelling Myspace as Mysplace, we'd expect it to show up in texts with Myspace also spelled correctly (since the misspelling wouldn't affect the recognition of correctly spelled instances of the word). Sure enough, here is just such an example, from a transcript of a panel discussion at the 2006 Web 2.0 Summit (oh, the irony):

Safa: Let me see, one of you, Ryan, you describe Misplace as...

Ryan: Myspace is like on Christmas morning when you go downstairs and there’s the presents under the tree, because when I sign on I see I have a new message or new friend request or comment, it’s like “ta-da!” I’m so happy I can’t wait to see who it is or what it is.

Safa: Everyone but Sheena and Pamela has a Myspace page.

Bernadette: I recently started because my son told me I wasn’t with it so he showed me how to get a page. I also realized my 14 year old son is 17 on Myspace.

Remy: My mom tells me to get off because it’s so time consuming and fixing it up so you have the background and pictures so all your friends will be like “I like your Myspace, it’s nice.” It's not an everyday thing, but I spend two to three hours on Misplace when I do get on.

So there we see Myspace spelled correctly four times and "incorrected" twice, possibly from Mysplace. In other cases, misplace shows up as a replacement for Myspace but not myspace.com, as in this transcript from WMAZ Eyewitness News in Macon, GA (yet another report of police officers finding tips online):

OFFICERS GOT A TIP THAT BATES WAS ON A POPULAR SOCIAL NETWORK... CALLED MYSPACE.COM.

THEY FOUND OUT HE CHECKED HIS MISPLACE PAGE REGULARLY AT A PHILADELPHIA LIBRARY.

And here's a music review with links to myspace.com where we find misplace along with two bonus Cupertinos, Sounder Lerche for Sondre Lerche and Elvis Costless for Elvis Costello:

Apparently Sounder Lerche toured with Elvis Costless and was influenced greatly because of it. The experience pushed him to “write songs with his band in mind”. “Say it All”, “Phantom Punch”,” Airport Taxi Reception”, and “The Tape”, can be heard on his misplace page.

Another review on that page has Alines Modiste for Alanis Morrisette and Tore Amos for Tori Amos. Stop the Cupertino madness, people!

[Update #1: Stephen Jones points out that not only does the latest Word spellchecker give misplace as the first suggestion for Mysplace, it also gives it for Mispace. (Myspace is included in the spellchecker dictionary but is only suggested second.) So that gives two potential sources for the misplace Cupertino.]

[Update #2: Thierry Fontenelle of the Microsoft Natural Language Group weighs in here.]

Lower-cased initialisms

It is a small but not insignificant recent change in written English that in Britain the newspapers have started spelling acronyms in lower case with capital initial instead of all in caps. The Universities and Colleges Employers Association and the the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs are not UCEA and DEFRA, but (at least fairly often) Ucea and Defra. And in Times Higher Education magazine, the Higher Education Funding Council for England is now Hefce. This only applies to one of the two subclasses of what The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language chapter on lexical word formation (chapter 19) calls initialisms: it applies to the acronyms, not the abbreviations. Nobody calls the Science and Technology Facilities Council "Sftc", because you don't say "sftc" (could anyone?), you say "S F T C". Acronyms are more like words than abbreviations are, and the developing convention recognizes that.

By the way, as a couple of people have now pointed out to me, I ought to explain that as far as my judgments of what is a "recent" change in British English, your mileage may differ. I left Britain in July 1980 for a visit to the West Coast of the USA, and found it so enchanting that I refused to come back. From 1980 to 1994 I never even visited Britain. I worked as a professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz, learned plenty of American vocabulary and acquired post-vocalic [r], and saw very few British newspapers. I then moved to the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, and am still dealing with the language issues (there are words like chav in the newspapers now that I never knew at all). So when I say "recent" about British English, there is a strong probability that the recency illusion is in play. Recent for me is any time since 1980, because I've only just noticed it. For heaven's sake don't think I'm unaware of this: when I give my impression that something has recently been shifting or emerging in British English, you should take it with a large grain of salt and be prepared to give up to about 25 years of inaccuracy about dating of changes. Jesse Sheidlower tells me that British newspapers were at least sometimes spelling AIDS as Aids (notice, not aids, though — it's still an initialism in origin) before the end of the Reagan administration.

The blog Testy Copy Editors has discussed the issue. There zythophile notes the interesting example of VOIP: it looks like a word, but people say "V.O.I.P.", not "voip", so it is never Voip in British newspapers, always VOIP. It's an abbreviation, not an acronym.

Depending on the kindness of spellcheckers

From the Cupertino mailbag comes a note from Charles Belov, who writes in with a spellchecker-induced slipup that made its way into a work of literary criticism from a major American publisher. The following appears in Still Acting Gay by John M. Clum (St. Martin's Press, 2000), page 122:

(Image from Google Book Search.)

I don't think there's any way to read this passage charitably — as opposed to this blog post where "A Stretcher Named Desire" is used as a playful reference to the artist Frank Stella's stretcher-shaped creations, or this satirical piece from the University of Oregon newspaper in the late '70s reviewing a performance of "Kafka's only humorous play" entitled "Over the Roar of the Greasepaint, I Heard the One Who Flew Over the Loon's Nest Call Me Jean Brodie On a Stretcher Named Desire." There's nothing jocular about the use of Stretcher for Streetcar in Clum's book, so it does seem to be, as Belov puts it, an "obvious Cupertino" (and "one more item of proof that proofreading in commercial book publishing has gone downhill in the last 10-15 years").

Streetcar appears properly elsewhere in the text (even later in the same paragraph), so this isn't a case of a spellchecker not recognizing a correctly spelled word, leading to the wholesale substitution of one word with another. Rather, this appears to be that subspecies of Cupertino wherein a single misspelling is "incorrected" thanks to a spellchecker suggestion. (Compare, for instance, the recent case of "GOP cell phones" from the Associated Press.) Stretcar is the most obvious suspect for a typo that could be changed to Stretcher, though the few spellcheckers I tried either give no suggestions for Stretcar or correctly suggest Streetcar.

Feel free to send your own Cupertino discoveries to bgzimmer at ling dot upenn dot edu.

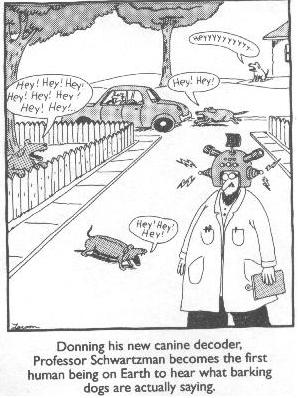

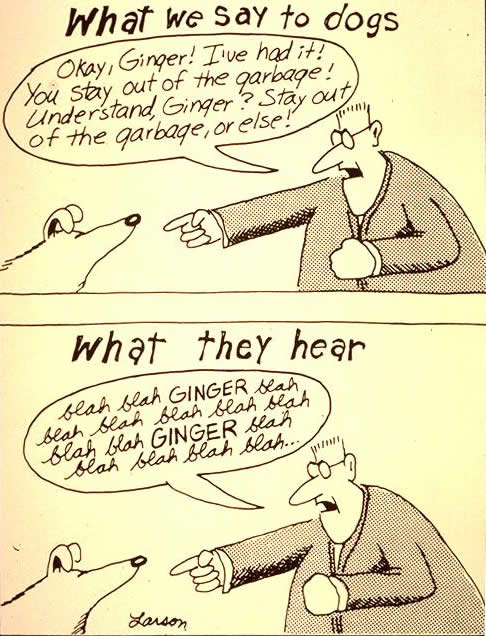

Bowlingual education, Critical Pet Studies, and human-poultry interaction

Are European researchers copying Japanese innovation in cross-species communication? This question arises in connection with our posts on Csaba Molnár et al. ("Classification of dog barks: a machine learning approach", Animal Cognition, published online 1/15/2008; see "It's a dog's life -- 0.3 bits at a time", 1/19/2008; "Dog language mailbag", 1/21/2008; "Not Prof. Milton, but Prof. Schwartzman", 1/21/2008). The issue was raised by Rob Troyer, who wrote:

Not to beat a dead dog, but a quick Google search of "dog translation" pulled up this Reuter article from 24 March 2003, "Dog translation device coming to U.S.", published at CNN.com/technology.

It discusses the "Bowlingual" a device "cited as one of the coolest inventions of 2002 by Time magazine" and developed with a cost of "hundreds of million of yen" by Tokyo-based Takara Company Ltd.

"The console classifies each woof, yip or whine into six emotional categories -- happiness, sadness, frustration, anger, assertion and desire" much like the computer program in the recent paper by the Hungarian researchers.

According to the article some 300,000 of these devices were sold in Japan in 2002-3, and the company was hoping to meet great success with its English version in the US which "is home to about 67 million dogs, more than six times the number in Japan."

The Wikipedia article on the Bowlingual links to an inspiring Takara press release about the potential impact of interspecies communiation on world peace("Bowlingual Presented to Russian President Putin by Japanese Prime Minister Koizumi", 5/30/2003):

The devices were prototypes of the U.S. version, currently in the final phase of testing, and included prototype English packaging and English user manual. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Russian Division, also assisted in the preparation of a summary of the user manual in Russian. Although the prototypes were available only in Red, they were adjusted to two different frequencies and labeled accordingly so that they could be used together with President Putin's two dogs--a standard feature when using two different-colored off-the-shelf Bowlingual units. The units' Set Up menus were also set to match the breeds of the President's dogs, which were said to be a standard Poodle and a Labrador Retriever.

It with great pride and satisfaction that Takara has been able to help facilitate the bonds of friendship between two leaders, Prime Minister Koizumi and President Putin, as well as promote peace and strong international relations between Japan and Russia.

Alas, Wikipedia's reference to the Bowlingual web page links via the Wayback Machine -- suggesting that this is an ex-product. There's a 2003 SF Chronicle article that suggests why (Sophia Lin, "Gadget's bark is bigger than its hype: Vet puts 'bark translator' to the test. Verdict: nothing more than $120 curiosity", 8/16/2003).

Dr. Lin describes some informal tests, in which the Bowlingual seems to perform non-randomly but also uninformatively, and concludes:My final ruling? The Bowlingual is fun to play with for a while if you got it for free, but it's not very useful because the translations aren't trustworthy and most don't make sense. The toy is marketed as being backed by strong science carried out by respected researchers but somehow, despite their accolades, they produced a dud.

I haven't been able to figure out who the "respected researchers" were, or where their "strong science" was published. In particular, I was unable to find any references to the Bowlingual in the machine-learning or animal-communication literature. Google Scholar does turn up some published discussion by literary scholars, including B. Lennon, "Misunderstanding Media: The Bomb and Bad Translation", Criticism, 2005; H.J. Nast, "Loving ... Whatever; Alienation, Neoliberalism and Pet-Love in the 21st Century", ACME; H.J. Nast, "Critical Pet Studies", Antipode 38(5):894-906. Unfortunately, none of these offer any information about the device beyond quotations from the popular press.

There is also at least one paper in the computer-science literature that mentions the Bowlingual, and it's a doozy: Shang Ping Lee, Adrian David Cheok, Teh Keng Soon James, Goh Pae Lyn Debra, Chio En Jie, Wang Chuang and Farzam Farbiz, , "A mobile pet wearable computer and mixed reality system for human-poultry interaction through the internet", Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 10(5) 301-317, 2006. The abstract is fascinating:

Poultry are one of the most badly treated animals in the modern world. It has been shown that they have high levels of both cognition and feelings and as a result there has been a recent trend of promoting poultry welfare. There is also a tradition of keeping poultry as pets in some parts of the world. However, in modern cities and societies, it is often difficult to maintain contact with pets, particularly for office workers. We propose and describe a novel cybernetics system to use mobile and Internet technology to improve human-pet interaction. It can also be used for people who are allergic to touching animals and thus cannot stroke them directly. This interaction encompasses both visualization and tactile sensation of real objects.

However, the paper's only information about the Bowlingual is this:

The growing importance of human-pet communication can also be seen in recent related company products. Recently, an entertainment toy company [12] has produced a Bowlingual dog language translator device. It displays some words on its LCD panel when the dog barks.

The reference is "12. TT Company http://www.takaratoys.co.jp/bowlingual", which is a dead link, suggesting again that this is an ex-product.

So, to sum up, it's hard to tell whether there is any connection between the pioneering but under-documented (and perhaps useless) Bowlingual, and the serious research described in detail by Molnár et al., demonstrated to derive 0.3 bits of information per doggie utterance. The idea of translating dog barks into six categories is similar, but the mapping between the Bowlingual six categories ("happiness, sadness, frustration, anger, assertion and desire") and the Hungarian researchers' six categories ("Stranger, Fight, Walk, Alone, Ball, Play") is not transparent. Neither Bowlingual nor Takara is mentioned in the Molnár et al. paper.

[On a related topic, I wonder how many patents on pet communication devices are out there...]

[Update -- at some point, Vodaphone released a Bowlingual-equipped cell phone, according to the Guardian's technology section (" Pet practice", 2/12/2004):

'Woof!" It might sound like a meaningless bark but, in fact, the dog is saying "Ya ne! Soba ni konai de!" (Hey! Don't come near me!). And while a European might make the mistake of approaching the diffident hound, Japanese dog owners would know to steer clear. Why? Because their phones would translate for them.

Bowlingual, a mobile application available to Vodafone subscribers in Japan, has a repertoire of about 200 dog phrases. It's just one of the many strange but innovative mobile products available in the Far East - and another reminder of how far ahead the Japanese are in non-voice applications.

It's not clear whether the upgrade from 6 to "200 dog phrases" represents a genuine research breakthrough, or a simple hack (e.g. choosing randomly among multiple "translations" for each of 6 categories), or just a random journalistic misunderstanding.]

[Update #2 -- a lead! The 2002 "Ig Nobel Peace Prize "

... went to Keita Sato, President of Takara a major Japanese-based toy company, Dr. Matsumi Suzuki, President of Japan Acoustic Lab and Dr. Norio, Kogure Executive Director of Kogure Veterinary Hospital for Bowlingual, their dog-to-human translation device in "promoting peace between the species."

Unfortunately, neither Suzuki nor Kogure seems to have published anything on a relevant topic, at least in English. And the recent Molnár et al. paper does not appear to reference any work by Japanese researchers of any name.]

[Update #3 -- a bit of searching turns up some patents. One is " Apparatus for determining dog's emotions by vocal analysis of barking, which tells us that

emotions represented by the reference voice patterns include "loneliness", "frustration", "aggressiveness", "assertiveness", "happiness", and "wistfulness"

The author is Matsumi Suzuki. I'm glad to say that the patent contains quite a bit of detail about the features and their claimed meanings.

Another is " Device and Method for Judging Dog's Feeling form Cry Vocal Character Analysis", for which Suzuki is also the inventor. In this case,

The reference voice patterns by feelings correspond to the feelings of 'loneliness', 'frustration', 'threating', 'self−expression', 'delight' and 'demand'.

]

Linguification extinct?

Just a word to thank the journalistic community at large for apparently giving up the practice of linguification, which used to puzzle me so much. I did catch someone on NPR saying in November 2006 that "when you say recount you know the word Florida can't be far behind" (totally false, of course: recount gets 4.8 million Google hits, while {recount Florida} gets only 166,000, so that means over 96% of the time a page with recount on it does not have Florida on it anywhere [but see below]). Then 2006 ended, and 2007 was blissfully free of linguifications as far as my recollections are concerned. Language Log apparently did not have to mention the word at all during last year. The term bloomed in July 2006, and flourished, and then like a fragile flower it was gone before that year ended, and with it the phenomenon to which it referred. No more occurrences of this strange trope — writing a demonstrably false claim about linguistic occurrences as a perverted way of expressing a (possibly true) claim about non-linguistic matters — were ever seen again. We have vanquished the practice.

Unless... Why do I have a sinking feeling that people are now going to start mailing my Gmail account with new sightings, and thus disappoint me in this matter? I should keep my big mouth shut (if that metaphor is appropriate for a blogger; maybe it would be better to say, I should keep my big paws off the keyboard).