October 31, 2005

More Dowdese

Fascinating. The "orange croqueted halter dress" that originally appeared in Maureen Dowd's piece in the New York Times Sunday Magazine has magically changed to "orange crocheted halter dress" in the online edition. (The Times can't hide from the Nexis, Proquest, and Factiva newspaper databases, however, all of which have archived the original version with croqueted.) The change was made without even a perfunctory correction note, typically found at the end of an online article. Perhaps this is how the Times usually deals with correcting typos that are not strictly errors of fact.

We'll need to see whether croqueted or crocheted appears in Dowd's soon-to-be-released book Are Men Necessary?, from which the Sunday Magazine essay was adapted. If croqueted is there, that means the goof slipped by the combined editorial forces of G.P. Putnam's Sons and the Times Magazine.

It's very possible, though, that Dowd's editors didn't initially correct the croqueted error because they simply assumed it was an example of the writer's usual playful take on the English language. Dowd's pop-culture-laden wordplay, which pleases some and annoys others, was evident throughout Sunday's essay. Here are a few annotated examples of the latest Dowdese.

After Googling and Bikramming to get ready for a first dinner date, a modern girl will end the evening with the Offering, an insincere bid to help pay the check.

Bikramming refers to Bikram Yoga, which involves vigorous exercises performed in a heated room. (The style of yoga was conceived by the entrepreneur Bikram Choudhury, who has trademarked the "Bikram" name.) Dowd first tried out Bikramming in an Aug. 29, 2001 column about "The Offering," where it appeared transitively: "A thoroughly modern young lady might be found Paxiling herself, Googling her date, Bikramming her body and pondering The Offering." Paxiling would refer to self-medication with the antidepressant Paxil. Clearly Dowd is a fan of creating verbal nouns from brand names, taking her cue from such recent neologisms as Googling and Botoxing.

Dowd continues with her reflections on women letting men pay for dates, and what men might expect in return (again cribbing from her Aug. 2001 column):

Jurassic feminists shudder at the retro implication of a quid profiterole.

"Quid profiterole" (which Chris Waigl describes via email as "eyebrow-raising") is a ham-handed pun, blending quid pro quo and profiterole. Not one of Dowd's best efforts — one can imagine her searching through the pro- entries in the dictionary hoping to find an appropriate food term.

The essay wraps up with this line, describing an imagined world twenty-five years from now:

With no power or money or independence, they'll be mere domestic robots, lasering their legs and waxing their floors — or vice versa — and desperately seeking a new Betty Friedan.

Here Dowd returns to the language of body care and its peculiar verbal nouns, such as lasering to refer to the process of laser hair removal. This is one of the better examples of Dowdian wordplay, as the throwaway "or vice versa" cleverly suggests an absurd chiasmus. And "desperately seeking" manages to evoke both Desperate Housewives and its cinematic predecessor in the bored-housewife genre, 1985's Desperately Seeking Susan. When Dowd isn't trying too hard, her mots can be quite bon.

The merits of true minds

If you checked www.whitehouse.gov this morning as I did, shortly after President Bush's nomination of Judge Samuel Alito for a seat on the U.S. Supreme Court, you may have noticed an interesting slip of the ear memorialized in the transcript of his remarks:

Judge Alito's reputation has only grown over the span of his service. He has participated in thousands of appeals and authored hundreds of opinions. This record reveals a thoughtful judge who considers the legal matter -- marriage carefully and applies the law in a principled fashion. He has a deep understanding of the proper role of judges in our society. He understands that judges are to interpret the laws, not to impose their preferences or priorities on the people. [emphasis added]

The president's text must have read "a thoughtful judge who considers the legal merits carefully". He said "the legal matter" by mistake, stopped, and substituted "merits". The person recording the presentation instead transcribed "marriage", which is much closer to "merits" phonetically than orthographically: ['me.ɹɪdʒ] vs. ['me.ɹɪts] in IPA -- at least for people like me (and President Bush?) who pronounce merry, Mary and marry the same way.

By the time I checked again at 10:30, the transcript had been corrected to read "merits", as it should. But I wondered why the error had been made in the first place. This is not one that we can blame on an errant spellchecker. I briefly considered the possibility that some West Wing stenographer might be spending too much time thinking about gay marriage. Then I realized that this was almost certainly the result of one of the real-time transcription technologies -- either stenotyping (which uses a special chording keyboard) or voicewriting (which uses automatic recognition of shadowed speech). Everyone knows stories of speech recognition gone wrong, and there can often be mistakes in the results of stenotyping as well. Talking in real time is hard enough -- transcribing in real time is even harder.

Buckingham Browne and Nichols

Daniel Barkalow mails me with the story of another piece of awkward coordinative nomenclature resulting from a merger of schools in my current city of residence. There's a fairly well-known private school in Cambridge called "Buckingham Browne & Nichols", abbreviated as BB&N. The interesting oddity, Daniel points out, is that the name doesn't have any commas in it. (It contrasts, coincidentally, with another Cambridge institution, the research company Bolt, Beranek and Newman, abbreviated BBN, named by a ternary coordination.) BB&N was formed by a binary merger of the Buckingham school (for girls) and the Browne & Nichols school (for boys). When they agreed to merge, it is said, they wanted to avoid undervaluing either of the component schools, and they chose to signal this by just writing the names together, without any conjunction or punctuation. (This is common in the corporate world, of course, and there is an epidemic of it in publishing.) Daniel suggests that the effect is the opposite of what they wanted, making "Buckingham" look like a mere attributive modifier of "Browne & Nichols". I agree that the effect is not quite right, but I am not sure I agree about why. For me, the ampersand is salient enough to suggest that it marks the major break — that the first part is "Buckingham Browne" and the second part is "Nichols". In fact the effect is so strong that I can see Buckingham Browne in my mind's eye, his bow tie prominent against his bright pink shirt, his expensive suit impeccably unrumpled as he steps out of his Rolls Royce: "Hello; Buckingham Browne at your service. Mr Nichols, I presume?"

Brigham and Women's: it could have been worse

Bill Poser stopped to chat at the water cooler in 1 Language Log Plaza the other day, and remarked that the ugly coordinative name "Brigham & Women's Hospital", which appears to coordinate items in different grammatical functions (attributive modifier and determiner, respectively), could have been worse, much worse. What is now the Brigham and Women's Hospital results from a series of three separate binary mergers of what were originally four hospitals:

— the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital

— the Robert Breck Brigham Hospital

— the Boston Lying In Hospital

— the Free Hospital for Women

If you merged those last two you have had "the Free and Boston Lying In Hospital for Women", or "the Boston Lying In and Free Hospital for Women", or any of a number of other awkward names. A merger of the first and third might have produced "the Peter Bent and Boston Lying In Hospital" or "the Boston Lying In and Peter Bent Hospital"... So perhaps we were lucky.

Needling the Times

On the subject of spellchecker artifacts in the New York Times, the Boston Globe's Jan Freeman emails the following oddity from Maureen Dowd's piece in the Sunday Magazine, "What's a Modern Girl to Do?":

Cosmo is still the best-selling magazine on college campuses, as it was when I was in college, and the best-selling monthly magazine on the newsstand. The June 2005 issue, with Jessica Simpson on the cover, her cleavage spilling out of an orange croqueted halter dress, could have been June 1970.

Freeman writes: "I can't figure out what typo a spellchecker might turn into 'croqueted,' but I'm having trouble believing a human (two, three humans!) could miss this, too."

I'm not so sure a spellchecker can be faulted for this one. Dowd clearly meant crocheted, but using that word probably would not have bothered the spellchecker since it's common enough to be in the Microsoft Word custom dictionary (unlike, say, truthiness or DeMeco). And there's no likely candidate for a misrecognized typo here (unlike aquainted getting changed to aquatinted or amature to armature) — unless the typo was crocqueted, which is already pretty close to croqueted. Of course, if croqueted was in Dowd's copy to begin with, you can't blame the spellchecker for not recognizing that it was inappropriate for the context (though we can perhaps imagine a day when a superintelligent spellchecker would raise a red flag at collocating croqueted with halter dress).

Rather than spellchecker interference, this appears to be a simple mixup between two similar words of French origin. It's more of a malapropism than an eggcorn, since it's hard to imagine a semantic link between needlework and lawn games. There is in fact a rather obscure etymological connection: both crochet and croquet ultimately derive from Old French croche meaning "hook" (in one case referring to the hooked crochet needle and in the other to the crooked stick used in early forms of croquet). That at least explains the surface resemblance of the two words, differing only by digraphs (-ch- and -qu-) representing single consonants.

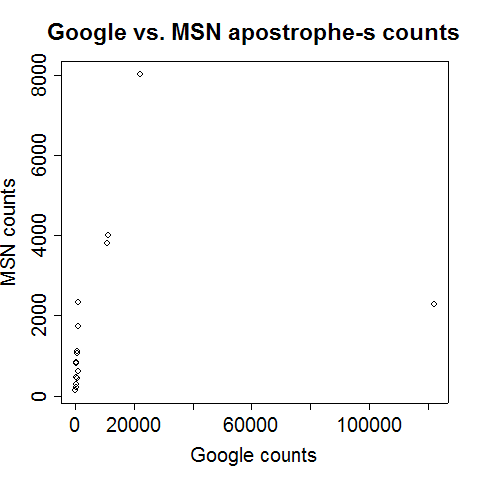

Still, as Freeman suggests, it is a bit surprising that this slipped past the copy editors at the Times. It's not an uncommon error in unedited text, as Google and Yahoo turn up scores of "croqueted sweaters" and the like — even after filtering out word lists, random text spam, and legitimate examples of croqueted (e.g., "I should have croqueted the Queen's hedgehog just now" from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland). A search on eBay auctions currently finds 14 crocheted items described as croqueted, with another 21 sold by eBay Stores. But we do hold Maureen Dowd and her editors to a higher standard than eBay vendors. What's more, this is in a piece for the Sunday Magazine, where the editing process is presumably more deliberate than it is for the daily paper.

Bonus dormitat Homerus. Far

more outrageous errors have been published and corrected by the Times,

as lovingly

recounted in the book Kill Duck Before

Serving. Here are two of my favorites (both also noted by Slate's Jack Shafer):

May 30, 1993

Because of a transmission error, an interview in the Egos & Ids column on May 16 with Mary Matalin, the former deputy manager of the Bush campaign who is a co-host of a new talk show on CNBC, quoted her incorrectly on the talk show host Rush Limbaugh. She said he was "sui generis," not "sweet, generous."April 7, 1995

Because of a transcription error, an article about Senator Alfonse M. D'Amato's remarks about Judge Lance A. Ito misquoted the Senator at one point. In his conversation with the radio host Don Imus, he said: "I mean, this is a disgrace. Judge Ito will be well-known." He did not say, "Judge Ito with the wet nose."

[Update, 4:40 PM: Perhaps someone on the Times editorial staff reads Language Log, since croqueted has been changed to crocheted in the online version of Dowd's essay. Details here.]

October 30, 2005

The first "Fitzmas"

Tracking neologisms in American English has a long and distinguished tradition. An early master was Dwight Bolinger (1907-1992), who began keeping tabs on the latest words and phrases in 1937 with his regular column "The Living Language" in the journal Words. In 1941 he moved the feature to American Speech (the journal of the American Dialect Society) under the title "Among the New Words," where it continues to this day, currently entrusted to Wayne Glowka. One able inheritor of Bolinger's mantle is Grant Barrett, project editor of the Historical Dictionary of American Slang and keeper of the entertaining and illuminating website Double-Tongued Word Wrester.

As a repository of "undocumented or

under-documented words from the fringes of English," DTWW offers

both completed

entries and a queue

of new citations that may eventually warrant full treatment in the

entry section. One recent item in the queue is an unusually successful

neologism, exploding out of nowhere into seeming omnipresence in a

matter

of a few weeks: Fitzmas.

Pending a full DTWW entry, let's turn to Wikipedia for a definition:

Fitzmas is the name given by some liberal American bloggers to the atmosphere of excitement and anticipation primarily among Democrats and some others preceding the announcement of results of Patrick Fitzgerald's investigation of the Plame affair. On October 28, 2005 Fitzgerald announced that the grand jury had indicted Lewis Libby, who was then the Chief of Staff and assistant for National Security Affairs to Dick Cheney, Vice President of the United States (Libby also served as Assistant to the President). The word "Fitzmas" is a portmanteau of Fitzgerald's name and "Christmas".

Staggeringly enough, Fitzmas

currently yields in the neighborhood of half a million hits from both Google and Yahoo. So who

coined Fitzmas? The DTWW queue

lists an Oct. 6 blog entry from 2Millionth Web Log,

while the most recent version of the Wikipedia entry cites a different

source from Oct. 6, a forum post on Democratic Underground.

Clearly what we need here is a tick-tock, as

they say in the news business. And thanks to blog trackers like Technorati and Google Blog

Search, we can provide just that. (Keep in mind, however, that only the first two entries specify the time zone!)

Oct 6, 2005, 1:04 AM PDT: Markos "Kos" Moulitsas Zúniga, on his immensely popular left-leaning blog Daily Kos, starts the ball rolling:

I get up at around 8:00 a.m. pacific time, or 11 a.m. Eastern. I hope I wake up to good news. This makes me feel like the night before Christmas:

The federal prosecutor investigating who leaked the identity of a CIA operative is expected to signal within days whether he intends to bring indictments in the case, legal sources close to the investigation said on Wednesday. [etc.]

Oct 6, 2005,

1:07 AM PDT: A few minutes after the Kos post, a contributor in

the comments

section named "Bob" takes a stab at what would be the first of many

parodies of Clement C. Moore's "A Visit from St. Nicholas," with other commenters following suit:

'Twas the night before Christmas

And all through the house

Not a creature was stirring

Not even the louse...

Oct 6, 2005, 4:20 AM: A blogger named "Attaturk" writes a longer parody of "The Night Before Christmas" in a post on the Rising Hegemon weblog:

KOS mentioned that this story made him feel like the night before Christmas.

So...

'Twas the night before Fitz talked,

when all through the house

Not a creature was stirring, not even a louse;

[etc., etc., with words and pictures]

But I heard Fitz exclaim, ere they drove out of sight,

"You're crooks one and all, and each I'll Indict."

Oct 6, 2005,

8:24 AM:

"Michael" on 2Millionth

Web Log links to the Rising Hegemon post and provides the first

known example of Fitzmas:

The Night Before Fitzmas, or a Visit From The Special Prosecutor

Rising Hegemon interprets an old classic.

Oct 6, 2005,

11:46 AM: In

an apparently unrelated development, "seemslikeadream" gets into the

Christmas spirit (inspired by Kos and his commenters?) in a forum post on Democratic

Underground:

The 12 Days of Christmas Indictments

I wonder if I could get a little help on this, been thinking of it since last night

On the first day of indictments my true love Fitz gave to me

One Rovian Frog March

Oct 6, 2005,

12:56 PM: In a

follow-up post in the Democratic

Underground forum thread, "SpiralHawk" offers the second known attestation of Fitzmas:

These are the 12 Days of Fitzmas

Get your Fitzmas On !

So it looks like this is a case of independent invention. Once the "Christmas" meme was planted by Kos, it spread along two different branches, both of which happened upon the Fitzmas portmanteau in short order. The Democratic Underground branch probably had more to do with the continued dissemination of the term after Oct. 6, as other forum posters continued coming up with Fitzmas parodies (e.g., on Oct. 9, "Botany" offered "Happy Fitzmas," a play on John Lennon's "Happy Xmas (War Is Over)," as well as yet another version of "The Night Before Fitzmas").

But the Fitzmas explosion didn't really hit until Oct. 18 when the meme returned to Daily Kos, this time in a widely linked post by "georgia10" with the title "Dealing With Fitzmas." Anticipation about impending indictments was high at that point, and it would only increase as bloggers and the news media continued to speculate about the timing and nature of Fitzgerald's announcement. On her own blog, "georgia10" commented on Oct. 22 about the spread of Fitzmas (a term she credited to Democratic Underground), noting that a Google search just four days after her Daily Kos post already yielded a whopping 51,500 hits.

We've come a long way from the days of Bolinger, when neologism-hunting was a laborious enterprise requiring eagle-eyed readers scouring newspapers and magazines for the latest lingo. Of course, not all coinages will deliver up their provenance as easily as a blog-driven term like Fitzmas. And it goes without saying that this kind of blogospherese may have an exceedingly short shelf life. Now that the announcement of the Libby indictment has passed, I would expect that Fitzmas will die out quickly — unless, of course, an indictment of Karl Rove or another high-level official is in the offing, in which case be prepared for Fitzmas II: A New Beginning.

[Update, 10/31/05: Goodness, those Wikipedists move fast. The Wikipedia entry has already been revised to include the 2Millionth Web Log citation.]

October 29, 2005

Scalia on the meaning of meaning

In the November issue of First Things, Justice Antonin Scalia has a review of

Law’s Quandary by Steven D. Smith. One of the review's central issues is the meaning of meaning. Scalia writes that

In the November issue of First Things, Justice Antonin Scalia has a review of

Law’s Quandary by Steven D. Smith. One of the review's central issues is the meaning of meaning. Scalia writes that

The portion of Smith’s book I least understand—or most disagree with—is the assertion, upon which a regrettably large portion of the analysis depends, that it is a “basic ontological proposition that persons, not objects, have the property of being able to mean.” “Textual meaning,” Smith says, “must be identified with the semantic intentions of an author—and . . . without an at least tacit reference to an author we would not have a meaningful text at all, but rather a set of meaningless marks or sounds.” “Legal meaning depends on the (semantic) intentions of an author.”

Scalia disagrees: for him, meaning has to do with understanding texts or utterances, not with intending to use them to communicate:

Smith confuses, it seems to me, the question whether words convey a concept from one intelligent mind to another (communication) with the question whether words produce a concept in the person who reads or hears them (meaning).

Even a phonetician like me knows that this issue had an important role in 20th-century philosophy of language. I present it to students in Linguistics 001 as the distinction between speaker meaning and sentence meaning, framed by a quote from Peter Strawson's essay "Logic and Truth" (reprinted in his 1971 collection Logico-Linguistic Papers):

What is it for anything to have a meaning at all, in the way, or in the sense , in which words or sentences or signals have meaning? What is it for a particular sentence to have the meaning or meanings it does have? What is it for a particular phrase, or a particular word, to have the meaning or meanings it does have?

[ . . .]

I am not going to undertake to try to answer these so obviously connected questions. . . I want rather to discuss a certain conflict, or apparent conflict, more or less dimly discernible in current approaches to these questions. For the sake of a label, we might call it the conflict between the theorists of communication-intention and the theorists of formal semantics. According to the former, it is impossible to give an adequate account of the concept of meaning without reference to the possession by speakers of audience-directed intentions of a certain complex kind. . . The opposed view. . . is that this doctrine simply gets things the wrong way round. . . the system of semantic and syntactical rules, in the mastery of which knowledge of a language consists -- the rules which determine the meanings of sentences -- is not a system of rules for communicating at all. The rules can be exploited for this purpose; but this is incidental to their essential character. It would be perfectly possible for someone to understand a language completely -- to have a perfect linguistic competence -- without having even the implicit thought of the function of communication

[. . .]

A struggle on what seems to be such a central issue in philosophy should have something of a Homeric quality; and a Homeric struggle calls for gods and heroes. I can at least, though tentatively, name some living captains and benevolent shades: on the one side, say, Grice, Austin, and the later Wittgenstein; on the other, Chomsky, Frege, and the earlier Wittgenstein.

I'm not sure that Chomsky is accurately classified here, but it's certainly fun to think of him as being on the same virtual debating team as Scalia.

On a more serious note, I'm curious about a different cultural divide -- the apparent separation over the past century or so between philosophy of law and philosophy of language, despite the evident overlap of issues. I haven't read Smith's book, but there is no 20th-century philosophy of language in the "scholarship, from ancient to modern, bearing upon the philosophy of law" that Scalia cites Smith as reviewing -- the list skips from Socrates and Plato to "Holmes to Pound, Llewellyn to Dworkin, Posner to Bork (and Scalia, honored as I am to be condemned in such eminent philosophical company)".

Scalia's specific arguments that meaning is something that (people perceive that) texts have, not something that people do (for the purpose of affecting other people), seem to me to raise some interesting non-linguistic issues. For example, he proposes this parable:

Two persons who speak only English see sculpted in the desert sand the words “LEAVE HERE OR DIE.” It may well be that the words were the fortuitous effect of wind, but the message they convey is clear, and I think our subjects would not gamble on the fortuity.

[...]

As my desert example demonstrates, symbols (such as words) can convey meaning even if there is no intelligent author at all.

This is a clear rebuke to William Dembski's information-theoretic approach to Intelligent Design Theory. If Scalia believes that the letters "LEAVE HERE OR DIE" sculpted in the desert sands are a plausible example of symbols with "no intelligent author at all", Dembski's notion of "specified information" (as evidence for an intelligent designer) has surely not impressed him.

When it comes to the meaning of meaning, Scalia not only focuses on the interpreter rather than the creator of a signal, he gives absolute power to semiotic convention:

If the ringing of an alarm bell has been established, in a particular building, as the conventional signal that the building must be evacuated, it will convey that meaning even if it is activated by a monkey.

I question the implication that people who hear a fire alarm interpret its meaning without paying any attention to theories of how it was activated: on Scalia's theory, how can we make sense of the everyday concept "false alarm"? When I'm told that a particular alarm is due to a circuit fault (or a mischievous monkey, though monkeys are thin on the ground in Philadelphia), I don't conclude that the conventional meaning of the fire alarm signal has changed, but I do join everyone else in aborting the evacuation. Back in January, Geoff Pullum told a real-world story that bears on this issue.

(And of course, the genuine human response to Scalia's LEAVE HERE OR DIE example would be to reason, at least briefly, about the author of the message and the intent behind it -- a threat? a prank? an improbable accident? the slogan of a defunct weight-loss camp, missing its last letter? If I'm one of the "persons" seeing the message, and the other one explains to me "Oh, that's just one of my cousin's tasteless jokes", I haven't learned anything new about the conventions of the English language, but the news alters my interpretation of the message profoundly.)

Scalia also argues (or rather asserts) that group exegesis is less ambiguous than group authorship, explaining that multiple authors "may intend to attach various meanings to their composite handiwork", while we can "ordinarily tell without the slightest difficulty" what the meaning of that handiwork was to its multiple contemporary readers:

What is needed for a symbol to convey meaning is not an intelligent author, but a conventional understanding on the part of the readers or hearers that certain signs or certain sounds represent certain concepts. In the case of legal texts, we do not always know the authors, and when we do the authors are often numerous and may intend to attach various meanings to their composite handiwork. But we know when and where the words were promulgated, and thus we can ordinarily tell without the slightest difficulty what they meant to those who read or heard them.

By citing three points where Scalia's arguments didn't convince me, I don't mean to invalidate the review as a whole, which struck me as an intelligent and interesting attempt to address important questions, and which persuaded me to order Smith's (rather expensive) book. However, I wonder whether Scalia has considered and rejected the ideas of the past century of philosophy of language, or whether he's simply never encountered them. It's obvious that the concerns of legislators, lawyers and judges overlap significantly with the subject matter of linguistics and language-related philosophy, and I've always been puzzled about why the real-world interactions between the disciplines and their practitioners seems to be so limited. Reading Scalia's review left me more puzzled than before.

If someone like Scalia were to want a reading list for philosophy of language since Plato, what should be on it? Works by Strawson's heroes and shades would not be at the top of my list of suggestions, but I'm not the one to compose such a list in any case. Send me your nominations, or (better) blog about it and send me the link, and I'll summarize the results in a week or so.

I gather from Scalia's review that Smith's perspective is at least as strongly represented among contemporary legal scholars as Scalia's is. I won't presume to characterize the philosophical state of play on these questions, but let me say that as a practical matter, linguists generally find it necessary to think about both kinds of meaning, in something like the relationship suggested by Wilson and Sperber's "Relevance Theory". This gives ontological houseroom to "linguistic meaning", but considers it one of the factors on the basis of which (a normally more consequential) "speaker's meaning" is inferred:

According to the code model, a communicator encodes her intended message into a signal, which is decoded by the audience using an identical copy of the code. According to the inferential model, a communicator provides evidence of her intention to convey a certain meaning, which is inferred by the audience on the basis of the evidence provided. An utterance is, of course, a linguistically coded piece of evidence, so that verbal comprehension involves an element of decoding. However, the linguistic meaning recovered by decoding is just one of the inputs to a non-demonstrative inference process which yields an interpretation of the speaker's meaning.

And let me add that it's often necessary to consider other aspects of the causal chain as well, such as transmission-channel noise and possible slips of the tongue, pen or ear. Along with the intrinsic ambiguities of the signals involved, this means that "decoding" itself is a non-trivial process, usually seen as a form of Bayesian reasoning that crucially depends on assumptions about the a priori probability of alternative (linguistic) messages as well as on the available evidence about the signal being decoded. I suppose that legal texts are generally carefully composed and proofread, but errors must occasionally creep in -- and do obvious typos or malaprops then have the force of law?

[Update: more here and here. And some blawg discussion by Eh Nonymous at Unused and Probably Unusable. And a very relevant Georgetown Law Journal article by Larry Solan, "Private Language, Public Laws: The Central Role of Legislative Intent in Statutory Interpretation", for which a preprint is available here.]

Coordinative naming botches

I have noticed while walking about Cambridge, Massachusetts, that it has at least two institutions with names that result from mergers that took place in their pasts and ended up being close to ungrammatical. One is the Cambridge Rindge and Latin School. Another, in the news this weekend, is the Brigham and Women's Hospital. Both these coordinate names sound strikingly weird to me. It is worth trying to diagnose the syntactic reasons.

Cambridge Rindge and Latin is the only public high school in Cambridge, and I think its name sounds wrong because it coordinates a proper-name modifier associated with the name of the founder (Frederick Hastings Rindge) with a modifier that appears to designate a subject matter taught (the Latin language). So it's odd in the same way that it would be odd if a place called Bagley Farm merged with a place called The Dairy Farm and the result was called "the Bagley and Dairy Farm"; or if the two units at Harvard called the Kennedy School of Government and the Harvard Divinity School were to merge into something called "the Kennedy and Divinity School". (That one looks bad enough that mentally I place an asterisk in front of it.)

Cambridge Rindge and Latin resulted from a merger of the Rindge School of Technical Arts with the Cambridge High and Latin School. But of course the latter is itself a coordinative naming botch; the Cambridge High and Latin School was formed as a result of an earlier merger of Cambridge English High School and Cambridge Latin School. "High and Latin" is a coordination of an adjectival modifier with a proper-noun modifier, and sounds just as weird. (We're lucky we didn't get "Cambridge Rindge, High, and Latin", a coordinative amalgamation of all three.)

Brigham and Women's Hospital was in the news over the last few days because Luk Van Parijs, the MIT associate professor who has just been fired for faking data in several immunology papers, did some of his research there.

The linguistic problem with "Brigham and Women's" seems even worse than "Rindge and Latin" or "Kennedy and Divinity" to me. It's a coordination of a proper name modifier (as in the underlined part of London pride, Budapest Restaurant, or California girls) with a genitive noun phrase determiner (as in the underlined part of Ken's pride, Alice's Restaurant, or our girls). In general, it seems to me that you should expect any attempt to do this kind of coordination to make something crunchingly ungrammatical. See what you think (the square brackets indicate the coordinate constituents):

*[London and Mary's] pride is what you're dealing with.

*Let's go to [Budapest and Alice's] Restaurant.

*I like both [California and our] girls.

I think they should have called in a linguist in when they were discussing these mergers. You don't want your institution to get stuck with an ungrammatical name. It's the same as when you are coining a new word that you hope will catch on, or making an assertion about what phrases occur in current discourse. Language Log Plaza is happy to provide lingustic consultants on such matters. Our fees are reasonable, and our linguistic taste is guaranteed: if there are any problems with the new name we create, we are prepared to give you your old name back.

Don't read it as something more than it's not

The punditocracy and the blogosphere, from right to left, have generally been impressed by Patrick J. Fitzgerald's news conference yesterday. I share this positive evaluation, but I want to use it as background for a different point. Speaking demands skill; explaining something complicated in public to a large audience is stressful; and when the large audience is poised to interpret every nuance to the nth degree, with enormous stakes riding on the results, it's amazing that anyone ever manages to bring it off without mistakes.

Well, the truth is that almost no one ever does, and yesterday's performance by Mr. Fitzgerald was no exception to this generalization.

First, let's take a quick look at the reaction. Andrew Sullivan's evaluation:

WOW: Just a comment on the press conference. Fitzgerald is more than impressive. His focus, grasp of the relevant facts, clear enunciation of what he is doing and dignified way in which he refused to speculate on anything else were, to my mind, deeply encouraging for anyone who cares about public life. He's an antidote to cynicism. The Jesuits who educated him should be very proud today. It will be very hard to slime him; and the administration would be very foolish to even think about it.

Pejman Yousefzadeh at Redstate.org was less effusive but similarly positive:

I thought that Fitzgerald's television appearance was very impressive. He was restrained but principled, he knew the case inside and out and he was clearly at the top of his game in answering the reporters' questions (in addition to showing a great deal of patience with stupid questions like the very last one asked).

I agree, but let's look at some details of his performance at the press conference. (Quotes are taken from the transcript on the NYT site; on a quick check, they seem to match the recording. Any boldface and/or italics was added by me.)

As evidence of how carefully Fitzgerald was monitoring what listeners might make of his words, consider this Q & A::

QUESTION: Mr. Fitzgerald, do you have evidence that the vice president of the United States, one of Mr. Libby's original sources for this information, encouraged him to leak it or encouraged him to lie about leaking?

FITZGERALD: I'm not making allegations about anyone not charged in the indictment.

Now, let me back up, because I know what that sounds like to people if they're sitting at home.

We don't talk about people that are not charged with a crime in the indictment.

I would say that about anyone in this room who has nothing to do with the offenses.

We make no allegation that the vice president committed any criminal act. We make no allegation that any other people who provided or discussed with Mr. Libby committed any criminal act.

But as to any person you asked me a question about other than Mr. Libby, I'm not going to comment on anything.

Please don't take that as any indication that someone has done something wrong. That's a standard practice. If you followed me in Chicago, I say that a thousand times a year. And we just don't comment on people because we could start telling, Well, this person did nothing wrong, this person did nothing wrong, and then if we stop commenting, then you'll start jumping to conclusions. So please take no more.

Fitzgerald's first speech error occurs back at the very start of his presentation, in his second sentence:

FITZGERALD: Good afternoon. I'm Pat Fitzgerald. I'm the United States attorney in Chicago, but I'm appearing before you today as the Department of Justice special counsel in the CIA leak investigation.

Joining me, to my left, is Jack Eckenrode, the special agent in charge of the FBI office in Chicago, who has led the team of investigators and prosecutors from day one in this investigation.

As the papers explained, Eckenrode is actually from Philadelphia:

Mr. Fitzgerald announced the charges with John C. Eckenrode, Special Agent-in-Charge of the Philadelphia Field Office of the FBI and the lead agent in the investigation.

and Fitzgerald of course knows that, as he made clear later in the session:

We, as prosecutors and FBI agents, have to deal with false statements, obstruction of justice and perjury all the time. The Department of Justice charges those statutes all the time.

When I was in New York working as a prosecutor, we brought those cases because we realized that the truth is the engine of our judicial system. And if you compromise the truth, the whole process is lost.

In Philadelphia, where Jack works, they prosecute false statements and obstruction of justice.

When I got to Chicago, I knew the people before me had prosecuted false statements, obstruction and perjury cases.

Why then did he call Eckenrode "the special agent in charge of the FBI office in Chicago"? Well, it was obviously just a slip of the tongue -- Chicago persisted from the the previous sentence, and intruded into a place where it didn't belong.

Fitzgerald committed another type of performance error in his answer to the first question:

OK, is the investigation finished? It's not over, but I'll tell you this: Very rarely do you bring a charge in a case that's going to be tried and would you ever end a grand jury investigation.

At least for me, the italized sentence is somewhere between terminally awkward and out-and-out ungrammatical. If he were writing the answer out, I'm sure he would have backed up and reworded it. But he's speaking, and so he has to keep going and work it out somehow.

[If you care about the details... What he's saying, it's clear, is that a prosecutor normally keeps a grand jury involved during the period between indictment and trial, so that new charges can be brought if appropriate. He starts out by putting this in a negative way: the contrary would happen "very rarely". What would happen very rarely is something like "you bring a charge and you end the grand jury investigation". Having started with "very rarely", he inverts the subject and auxiliary of the first clause: "very rarely do you bring a charge in a case that going to be tried". So far so good, but now he's stuck: not inverting the second conjunct would be very odd, while inverting it is hardly any better. Furthermore, he feels the need to stick in would so as to emphasize that the whole thing is hypothetical, since he apparently doesn't want to give any detailed facts about which grand juries are looking into what.]

Another type of error comes up in answer to a later question (pointed out to me by Eric Bakovic):

FITZGERALD: You couldn't walk in and responsibly charge someone for lying about a conversation when there were only two witnesses to it and you talked to one. That would be insane.

On the other hand, if you walked away from it with a belief that that conversation may have been falsely described under oath, you were walking away from your responsibility.

And that's why, when the subpoenas were challenged, we put forward what it is that we knew and we let judges pass on it.

So I think people shouldn't read this exceptional case as being something more than it's not.

As Arnold Zwicky observed via email, this apparently is a blend of

(as being something) that it's not

(as being something) more than it is

Let me emphasize again that I found Fitzgerald's presentation clear and impressive. My goal in pointing out some of his errors is not to cast a shadow on his considerable skill as a public speaker. On the contrary, these examples underline the fact that even impressive public speakers make lexical, grammatical and semantic mistakes in extemporaneous speaking, especially when the interpretive stakes are high.

This is a lesson that Jacob Weisberg and the other promoters of the Bushisms industry haven't learned, or more likely don't care to learn. As we keep explaining, people shouldn't read W's verbal blunders as being something more than they're not.

[Update: John Lawler emailed:

The first error I twigged to was one in the first selection you posted, but you didn't comment on it:

Conjunction reduction has overapplied to the first disjunct VP; probably he meant to say 'provided information to' or something, but the rest of the VP with 'provide' got sluiced away, leaving 'Mr. Libby' as its erstwhile object. It's a good example of precisely what you're talking about in the post. Also a good example of how cooperative we listeners and readers are, even when we're on the lookout for mistakes."We make no allegation that any other people who provided or discussed with Mr. Libby committed any criminal act."

Exactly. ]

October 28, 2005

Is splanchnic just another word for schmuck?

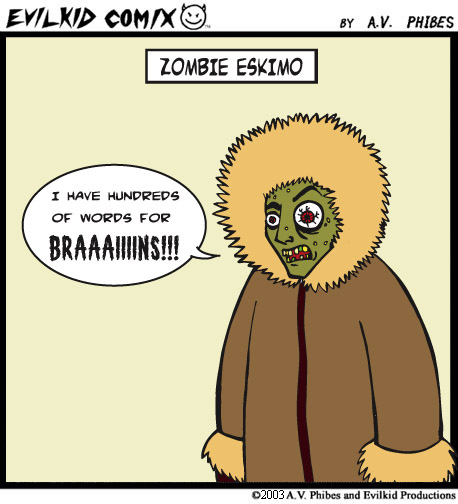

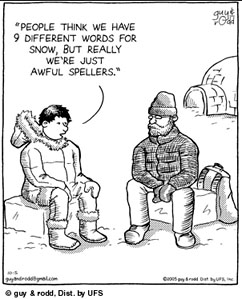

Over on the Logic and Language blog, my recent postings on "splanchnic" have elicited the quoting (by "logician") of a wonderful passage from Jonathan Safran Foer's Everything Is Illuminated that allows us to connect words in "-nik" (which "splanchnic" is not, though Roz Chast chose to treat it as if it were) with the World Famous Eskimo Snowclone. Here's the text, very lightly edited:

400 Words for Splanchnik

Arnold Zwicky over at languagelog has had a couple of posts about the word "splanchnik" recently... and given languagelog's fondness for jokes about the Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax,... I couldn't resist posting this excerpt from the novel I'm reading:

(Context: the Jewish-American hero-abroad is having a conversation with his Ukrainian guide. I've retained the non-standard layout of conversations from the original.)

Have I mentioned that "splanchnic" is on the tip of everybody's tongue these days? Hardly a day goes by...

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

In or under

It's a working assumption of linguists that when there are alternative expressions, the choice between them is neither completely free nor completely determined. Extreme prescriptivists would like to maximize determination, and to make the basis for determination explicit: in any context, only one alternative should be acceptable; there should be a good reason for this choice; and it should be possible to articulate that reason. Pick either "in the circumstances" or "under the circumstances", and be ready to justify your choice as the right one.

Linguists, studying language in actual use, point out that there is an

enormous amount of variation in these choices (variation between

speakers, and within a given speaker, variation in different linguistic

and non-linguistic contexts); that the choices are mostly matters of

(rather subtle) preferences rather than crisp decisions; that these

preferences interact with one another in complex ways; and that hardly

any of these preferences are easily accessible via conscious

reflection. You can ask people whether they would choose "in" or

"under", and why, and with the options presented side by side this way,

they're likely to express a preference and to produce some rationale

for it, but there's absolutely no reason to think that their accounts

are reliable. You have to look at what they actually do.

(Judgments based on side-by-side comparisons are tricky and

context-dependent even in situations where you might think they'd be

straightforward, like the Pepsi Challenge discussed by Malcolm Gladwell

in Blink, pp. 158-9.)

In my

recent posting on "in the circumstances" vs. "under the

circumstances", I started to move beyond side-by-side comparisons and

into some (admittedly crude) statistics on actual use, uncovering a

modest preference, in a Google web search, for "under" as opposed to

"in", contrary to the advice of some prescriptivists. Now

I've gone a bit further, and it looks like there's some interesting

texture to the variation in this preposition choice.

A brief recap: the raw Google webhit figures were:

under the circumstances: 3,980,000 (in/under ratio: 0.83)

Now, I'm quite sure that there are between-speaker differences in the choice of "in" vs. "under" with "circumstances", but corpus searches like this aren't going to find them. And for individual speakers, I suspect that there is variation according to modality, style, and a number of other "external" factors, but again searches like this won't turn them up. What we can look at are factors that have to do with linguistic context, and here we strike paydirt very quickly.

First, MWDEU claims that when "circumstances" means 'financial situation', "in" is the preposition of choice, and "under" is rare. Googling supports this claim:

under reduced circumstances: 174 (ratio: 141.38)

This overwhelming preference for "in" extends to "circumstances" in the sense of 'personal situation' in general. With some possessive determiners:

under their circumstances: 751 (ratio: 111.58)

in your circumstances: 98,400

under your circumstances: 1,940 (ratio: 50.72)

in my circumstances: 36,000

under my circumstances: 1,470 (ratio: 24.49)

(There might be something in the difference between the pronouns, but I'm not exploring that today.)

On the other hand, the modest preference for "under" extends to PPs with the demonstrative "these" (my thanks -- I guess -- to Elizabeth Zwicky for suggesting that I look at determiners other than "the"):

under these circumstances: 3,020,000 (ratio: 0.94)

and then balloons for interrogative/relative "which" and interrogative "what":

under which circumstances: 134,000 (ratio: 0.46)

in what circumstances: 318,000

under what circumstances: 1,680,000 (ratio: 0.19)

Now a surprise. For demonstrative "those", "in" is preferred:

under those circumstances: 646,000 (ratio: 1.66)

As it turns out, the figures for "in" here are somewhat inflated by occurrences of "those circumstances" with a following relative clause in "where" or "in which", a context in which -- another surprise -- "in" is almost categorically preferred to "under":

under those circumstances where: 538 (ratio: 137.73)

in those circumstances in which: 16,000

under those circumstances in which: 240 (ratio: 66.67)

Removing these occurrences from the overall "those" count leaves:

under those circumstances: 645,222 (ratio: 1.52)

There's still a fairly sizable preference for "in" with "those", in contrast to "these".

(There are only small numbers of other relative clause types with "those circumstances", for example:

under those circumstances under which: 12

in those circumstances which: 566

under those circumstances which: 497

in those circumstances for which: 66

under those circumstances for which: 34

I wouldn't try to draw any conclusions from these small differences.)

When we turn to quantity determiners, there seems to be a general preference for "in" over "under":

under all circumstances: 981,000 (ratio: 1.33)

in some circumstances: 2,850,000

under some circumstances: 1,760,000 (ratio: 1.62)

which becomes very strong for "many":

under many circumstances: 48,500 (ratio: 6.14)

and almost categorical for "a few":

under a few circumstances: 462 (ratio: 46.10)

but is utterly reversed, in favor of "under" (almost categorically), for "no":

under no circumstances: 6,260,000 (ratio: 0.05)

In summary: the Google data suggest that "under" is preferred to "in"

with determiners "the" and "these"

(more strongly)

with determiner "which"

(very strongly)

with determiner "what"

(almost categorically)

with quantity determiner "no"

but that "in" is preferred to "under"

when "circumstances" means 'personal situation'

(strongly)

with determiner "those" in general

(almost categorically)

with determiner "those" plus certain following relatives

(modestly)

with quantity determiners "all" and "some"

(strongly)

with quantity determiner "many"

(almost categorically)

with quantity determiner "a few"

This just scratches the surface of the phenomenon, but it's enough to indicate that several effects are probably going on. As usual, the facts of usage are complex, subtle, sometimes surprising, and not easy to derive from first principles.

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

The longue duree is not our forte

An article about English usage by Candace Murphy in the Oct. 25 edition of "Inside Bay Area" (a publication of the Oakland Tribune) underscores the pitfalls of the "Recency Illusion" that Arnold Zwicky has eloquently blogged about in this space (here, here, and here). The article, entitled "Good Words Gone Bad," takes the typical hell-in-a-handbasket approach to "language abuse," despite objections from the very experts that Murphy quotes.

The article begins as follows:

The word is harmless enough. It has five letters. It doesn't have an inordinate number of consonants or vowels. It is commonly used in conversation.

But nearly always, it is pronounced incorrectly.

And that rankles true verbivores.

"Oh, yes. 'Forte,'" says Paul Brians with a perceptible sigh, pronouncing the word meaning a person's strength as it should be, monosyllabically without a flourishing finish on the word's final vowel. "I've given up on that one. It's a dead issue. If you went around saying 'FORT,' people wouldn't know what you're talking about. It's an error that has become a non-error."

The use, or some might say, abuse, of the English language, and the standardization of non-standard English is endless. A joke is hysterical when it's really hilarious. People buy a chaise lounge when it's really a chaise longue. Forte, probably confused with the musical dynamic of the same spelling that's borrowed from Italian, gains an extra syllable.

The skeptical reader's warning bells should be set off right away with the assertion that a particular word, in this case forte, is "nearly always ... pronounced incorrectly." It is the same alarmist approach that led a writer more than a century ago to proclaim that "every journalist and every author wherever the English language is written" is guilty of "sloppy usage" because they insist on pluralizing person as people. Everyone is wrong, and only by recognizing our linguistic condition of original sin can we hope to atone for our wayward usage and get on the straight and narrow.

A second warning bell should go off upon reading the supposition that "true verbivores" are "rankled" by such atrocities as the two-syllable pronunciation of forte in its sense of "strength." Paul Brians, the keeper of the comprehensive "Common Errors in English" website, is certainly a verbivore of excellent standing, but he shows little sign of outrage about this putative linguistic transgression (besides the "perceptible sigh" that the reporter would like us to think is telling). What does Brians actually say? "It's a dead issue." "It's an error that has become a non-error." In fact, Brians has specifically listed the two-syllable pronunciation of forte on his page of "non-errors," a position he has further emphasized in a thread on the alt.usage.english newsgroup.

It's difficult to know exactly how long English speakers have been conflating French-derived fort and Italian-derived forte (both from Latin fortis meaning "strong"), but it's safe to say it's not a new phenomenon. The Oxford English Dictionary shows that the spelling of the "strength" sense as forte rather than fort has been in use since the 18th century (probably simply an adoption of the feminine form of the French word at the expense of the masculine, akin to other Gallic borrowings like locale and morale). The two-syllable form evidently developed some time after that as a spelling pronunciation, but it has long been recognized as the primary pronunciation of the word in both American and British English.

From this spurious example, Murphy makes a great leap in logic:

It's enough to make a lexicologist wonder: Are we all just a bunch of idiots?

"I don't think so," says Brians, a professor at Washington State University who manages the Web site "Common Errors in English" and who recently wrote a companion book called "Common Errors in English Usage" (William, James and Co., $15). "People have always abused language. The specific abuses they commit just change with time, so we notice the new ones."

But today, it's quite likely that those abuses and misuses are worming their way into standard English usage at a quicker rate.

Here we see a fascinating tension between Brians — the authority

who Murphy has brought in for the article (and author of a new

book that provides her news hook) — and Murphy herself, who has

clearly already made up her mind about the degenerative state of

English usage. Brians plainly lays out the Recency Illusion as it

applies to matters of disputed usage, but the reporter chooses to

ignore her own source to put forward the unfounded claim that "abuses

and misuses are worming their way into standard English usage at a

quicker rate." (The claim is prefaced by the journalistic weasel words

"it's quite likely," which we should translate as "I have nothing but

anecdotal evidence for what I am saying.")

Murphy doesn't enlist any actual subscribers to the

degenerationist point of view (say, a Robert

Fiske or John

Simon) but instead relies on Brians and the equally reasonable Erin

McKean, editor of the Oxford American Dictionary. Both make the point

that non-standard usage may appear to

be on the rise because we are exposed to so much more of it in

written form due to the explosion of online communication. (Coupled

with the rise of Google and other search engines, this easy

availability of an endless array of non-standardisms has spawned such

pastimes as eggcorn-collecting

and peeveblogging.)

Brians further notes in the alt.usage.english thread that "such reading

as people do is now often not professionally edited, which is a marked

change from the past." This certainly heightens the Recency Illusion,

though it doesn't necessarily imply what Murphy calls "the seeming

increase in language abuse" (again note the weasel word "seeming").

But wait! Not only are all sorts of non-standard words and

expressions spreading like wildfire across cyberspace, they're even

entering our hallowed

dictionaries!

Courtesy the Internet, those misuses, abuses, slang and shorthand are broadcast to the world, or at least, the World Wide Web, where they earn a standard usage of their own. Combine that with the fact that the new young crop of dictionary editors are more attuned with the Internet than their predecessors — McKean is one of the youngest, at 33, while the Oxford English Dictionary is helmed by Jesse Sheidlower, 36 — and it suddenly makes perfect sense why "podcast" is now in the dictionary.

"All the lexicographers I know who are in their 30s spend an unconscionable amount of time on the Internet," says McKean. "We're looking for language. Language is there."

That's where McKean has found words like farb (not authentic, badly done), nomenklatura (non-literally; by analogy), drabble (a short story of 100 words or fewer), haxie (a hack for the Macintosh operating system) and swancho (a combination poncho/sweater).

Though they're not in the dictionary yet, they may be coming soon to one near you. Each word is categorized by McKean as "on the brink." None of them may be right, correct, proper or even real. But McKean calls them innovations. And innovation, she says, is the essence of language.

Darn those young

Turks of lexicography and their blasted Internet! Murphy should

know, though, that the whippersnappers of the dictionary world are not

a bunch of radicals hellbent on tossing out the old reference books in

favor of Urban Dictionary.

In fact, despite their penchant for online research, they tend to take

the long view, patiently observing that in

every generation there are those who decry new usage as barbaric, as

somehow not "right, correct, proper or even real." And often that "new

usage" is not so new after all, since the same bugaboos, like the

pronunciation of forte as for-tay, keep getting hauled out

time and time again as evidence of our linguistic degeneration.

The Recency Illusion is powerful, though, and it's very easy to ignore the longue durée in favor of a kind of naive presentism. For some reason, that presentism is particularly alluring when it comes to the shifting sands of English usage.

[Update, 10/31/2005: If you were baffled by the mention of "nomenklatura (non-literally; by analogy)" in the list of Internet-derived innovations, Languagehat has the explanation straight from Erin McKean: "she had been talking about a nonliteral use of the word nomenklatura itself, 'that is, one that referred to people that weren't Russians, but were metaphorically similar to the Russian nomenklatura.'"]

[Update, 11/18/2005: The curmudgeonly comic strip character Mallard Fillmore, who previously railed against apostrophe abuse, took up the (lost) cause for monosyllabic forte in the Nov. 13 strip.]

Trademarking -ix

The Associated Press reports that a European Union court is about to rule on a trademark infringement suit filed by Les Editions Albert René, publisher of the Astérix comic books, against the mobile telephone firm Orange. What does Astérix have to do with mobile phones? Orange wants to register the trademark Mobilix for telephone services. Les Editions Albert René objects on the grounds that because Mobilix ends in ix people are likely to think that it is somehow associated with Astérix.

I don't know EU trademark law, but in the United States and Canada trademarks are only valid within a particular market sector, so in North America at least the publisher would have no case at all unless, contrary to fact, so far as I know, they had registered the trademark Astérix for telecommunications or can show that their mark is a so-called "famous name". Orange is not proposing to use the name Mobilix for a series of comic books that might compete with the Astérix books.

The linguistically interesting point here has to do with what association it is that the ending /iks/ conjures up. The publisher of Astérix claims that the association is with its series of books, in which, in addition to Astérix, a number of other characters have names ending in /iks/, such as his friend Obélix, the druid Getafix, and Astérix's dog Dogmatix. I suspect that there is actually something else going on.

The source of the suffix -ix in the Astérix books is the string rix in which the names of many actual Gaulish chieftains ended, such as Dumnorix, Vercingetorix, Orgetorix, Sinorix, Amborix, and Adiatorix. This rix consists of two morphemes: /rik/ "king" and /s/ "nominative singular case". It is the Gaulish cognate of Latin rex, whose stem is /reg/, as we see in forms such as the accusative singular regem and the nominative plural reges. The Astérix books have reanalyzed the ending rix as ix.

What I wonder is whether the association of words ending in ix is really specifically with the Astérix books or whether it is as much or more an association with things Gaulish. Names such as Vercingetorix are familiar to anyone with a classical education, in which one reads Caesar's memoir of the Gallic Wars, and should be familiar to most Western Europeans from their studies of European history. However, few people learn anything about Gaulish or for that matter the other Celtic languages, so people acquainted with such names may very well be unclear as to whether the suffix includes the /r/.

Prosodically (in)correct

From Frank DeFord's commentary about the new NBA dress code, 10/26/2005 on NPR's Morning Edition, this semantico-phonetically interesting passage:

So too did the Minnesota Vikings institute a dress code not long ago [breath]

and yet the Vikes remain as [breath]

beHAViorally INcorrect as they may be [breath]

sarTORially COrrect.

This is a matched pair of playful allusions to the phrase "politically (in)correct". The first few pages of web search results for incorrect yield the other adverbially (in)correct echoes conservatively, patriotically, therapeutically, commercially, musically, spiritually and environmentally, and there must be dozens if not hundreds more of them out there.

In DeFord's case, the paired allusions create a nice example of double contrastive focus and the use of phrasing for emphasis. The feature that caught my attention, though, was the intonational highlighting of the prefix in- and the word fragment co-.

A commoner sort of contrastive focus is exemplified by DeFord's contrast between behaviorally and sartorially. As part of the performancy of this contrast, he highlights intonationally the syllable of each word that is its normal main stress. This is the usual effect of contrastive focus in English: the pitch-contour effect is strongest on the main-stressed syllable of a focused word or phrase. But in the case of the contrast between incorrect and correct, the syllables that mainly inherit the phonetic effect are not the normal main stresses.

This sort of thing was discussed in Ron Artstein, "Focus below the word level", Natural Language Semantics 12(1): 1-22, 2004. Artstein cite an analogous example from Bolinger (1963):

natural REgularity (“in a context that implied an opposition to IRregularity”)

Here's a display showing a pitch contour, a spectrogram and a waveform for DeFord's contrasts:

This display was created with WaveSurfer, an "Open Source tool for sound visualization and manipulation" that I recommend for casual users because it's relatively easy to learn to use in simple ways. Another excellent open-source program, Praat, offers a much wider range of functions, and is also better for producing publication-quality graphics rather than simple screenshots like that shown above.

Miered in doubt

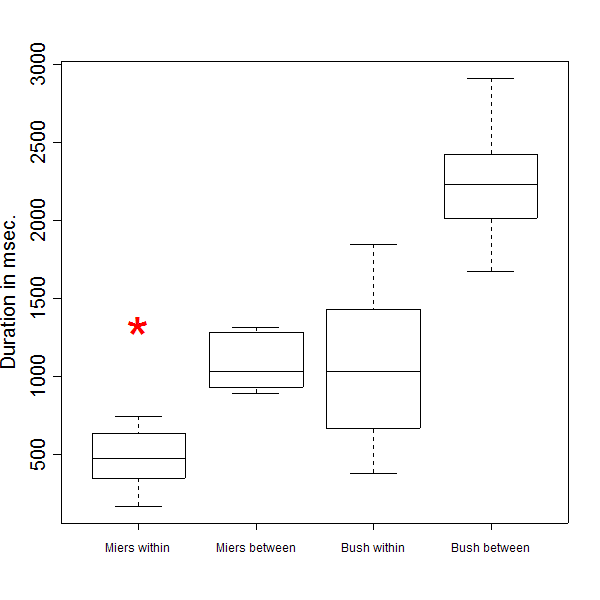

Now that she has withdrawn her name from the Supreme Court nomination process, what will the linguistic legacy of Harriet Miers be? Will she be remembered as a supposed stickler in matters grammatical who ran afoul of subject-verb agreement in her first public statement as a nominee? Or will history record Miers' punctuation style, either her "trouble with commas" in written responses to Senate questions or her exuberant use of exclamation points in correspondence with President Bush when he was governor of Texas?

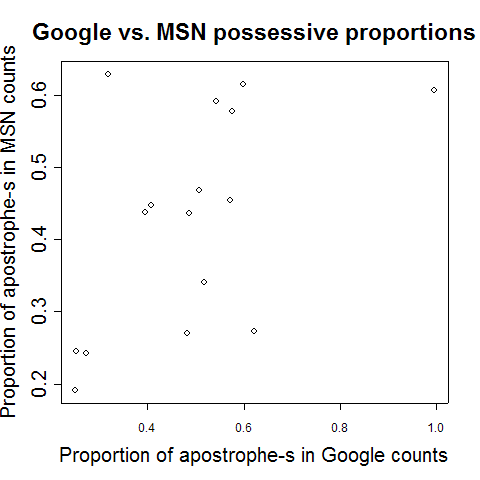

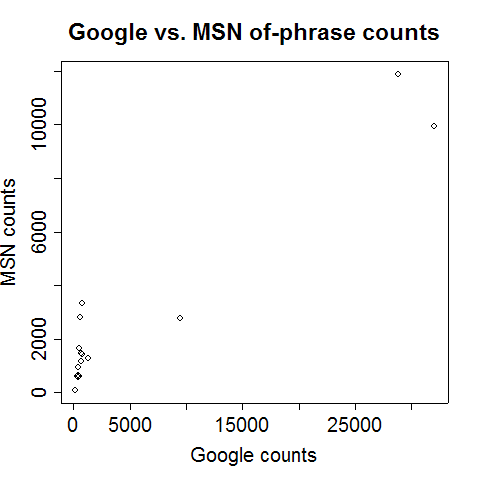

Perhaps Trent Lott is right to wonder, "In a month, who will remember the name Harriet Miers?" But an Associated Press article suggests that Miers' lasting legacy will only be her name, converted into a verb in the manner of Robert Bork, her predecessor in nomination termination (or "SCOTUS interruptus," as several wags have termed it). Like Bork, Miers has been eponymized primarily in the passive voice: Bork got Borked, Miers got Miered. Though Miered lacks the phonesthemic punch of Borked, it does of course have the benefit of being a pun on mired. Semantically there's a distinction too, according to the blogospheric sources quoted by the AP:

A contributor to The Reform Club, a right-leaning blog, wrote that to get "borked" was "to be unscrupulously torpedoed by an opponent," while to get "miered" was to be "unscrupulously torpedoed by an ally."

S.T. Karnick, co-editor of The Reform Club, elaborated.

"If you have a president who is willing to instigate a big controversy, the prospect of being 'borked' will be the major possibility," he said. "But if you have a president who is always trying to get consensus, then it's much more likely that nominees will get 'miered.'"

On The National Review Online, a conservative site, a contributor suggested that "to mier" means "to put your own allies in the most untenable position possible based upon exceptionally bad decision-making."

You don't have to fail in the Supreme Court nomination process to get your own verb. Justice David Souter was also eponymized, though it was well after his elevation to the Court. When the reticent John Roberts was announced as Bush's choice to fill Sandra Day O'Connor's anticipated vacancy, there was talk of him being Soutered. As CNN explained, "to 'Souter' has come to mean to pick a candidate without knowing much about him." It is presented as the opposite of getting Borked; where Bork had a voluminous record of legal opinions, Souter was an enigma at the time of his nomination by Bush Sr. and thus was difficult to attack during Senate questioning. But conservatives have also used Soutered to refer to the betrayal they felt when Souter joined with moderate to liberal opinions on the bench. "Won't get Soutered again," they vowed.

I note that one of the potential replacements for Miers, according

to the New

York Times, is Judge Diane Sykes of the Seventh Circuit. Is it too

early to wonder if conservatives would be Syked about her nomination?

October 27, 2005

Forbes Special Report

Forbes.com "Home Page for the World's Business Leaders" has taken a break from the accumulation of capital and oppression of the masses to publish a special report on Communicating with pieces by some well-known authors. There are a couple by Noam Chomsky On the Spontaneous Invention of Language and Why Kids Learn Languages Easily. You can hear his voice if you like here.

Legendary primatologist Jane Goodall has a piece on Why Words Hurt and another on The Dangers of Email. If you're interested in more monkey business there is an essay by Carl Zimmer entitled Can Chimps Talk?.

Stephen Pinker has a discussion of Why We Have Language and an audio clip on an What We Don't Know about Language.

The scope of the issue extends beyond linguistics, with pieces by writer Kurt Vonnegut, magician David Copperfield, futurist Ray Kurzweil, and even Walter Cronkite.

The generous village of Yuwawer

For months now my local NPR radio station (WBUR at Boston University) has asserted in a pre-recorded announcement that they play at least once an hour: "Our support comes from Yuwawer listeners." I imagined this place, some small village or township maybe, out in the Massachusetts countryside, or maybe up in New Hampshire, where the people were extraordinarily generous. Perhaps Yuwawer just happened to have residents who were mainly retired bond traders or Internet billionaires who made their money in the 1990s and got out before the downturn. I had no idea where Yuwawer was, but it seemed that the listeners there gave so much that the rest of us hardly needed to.

Only in the last few days did it finally dawn on me that there was no such place. "Our support comes from you, our listeners" is what they were saying. I got the message. I called the station and pledged. Do likewise. You know you should. The NPR fall fund drive is on now. Go pledge. My Republican friend Paul thinks NPR is outrageously biased in favor of the most extreme liberal Democrat ideas; my anarchist friend Jim thinks NPR is disgustingly subservient to right-wing Republican corporate and political pressures. So it really can't be all that bad, can it? Go to the phone now, and pledge generously. They do need the money. NPR is like Language Log, there to entertain and inform you every day, except that they have serious, major, ongoing staff expenses to cover.

Language Log is in a very different position. It is supported by grants of imagination from linguists across the country, and the construction of our office tower at Language Log Plaza was paid for by a generous contribution from the Yuwawer Retired Billionaires Foundation.

Artifacts of the spellchecker age

The New York Times has yet to issue a correction for the joke-ruining error in its Oct. 25 review of "The Colbert Report." This is somewhat surprising, since the Times prides itself on eventually rectifying even the most minuscule of typos that slip by the copy editors. According to Slate media critic Jack Shafer, there has been a "corrections culture" at the Times since the '70s, which "seems to revel in correcting every misspelling, transposed digit, historical inaccuracy, and boner." (The Times even authorized a book collecting its most amusing corrections, called Kill Duck Before Serving.)

But another recent error that did get corrected sheds some unexpected light on the situation.

In the Oct. 26 edition, we find this doozy

of a correction for a sports

article by Ray Glier:

Because of an editing error, a sports article in some copies on Sunday about the University of Alabama's 6-3 football victory over the University of Tennessee misstated the given name of a linebacker who is a leader of the Alabama defense. He is DeMeco Ryans, not Demerol.

Ouch! Warren St. John, one of Glier's fellow sports reporters at the

Times, saw the correction and had this to say on the blog for his Rammer

Jammer Yellow Hammer site:

All rightee then.

While we're at it, we've been meaning to run the following correction for a while: a previous post on the RJYH blog misstated the name of Alabama's head coach. It is Mike Shula, not God-I'm-dying-for-a-bourbon-and-water Shula.

How could Glier possibly have come up with Demerol instead of DeMeco? Could it have been some inside joke about the narcotic qualities of Alabama's defensive line? I doubt it. I think Glier innocuously wrote DeMeco in his story, but then a nefarious force changed the spelling for him: a runaway spellchecker. If you type DeMeco in a Microsoft Word document, you'll get the telltale squiggly red underline that indicates the word is not in the custom dictionary. And if you ask for a suggestion, the very first alternative provided is none other than Demerol.

So what about Alessandra Stanley's goof,

replacing Stephen Colbert's sublimely silly truthiness with the pedestrian trustiness? I had assumed the error

was a sort of anticipatory

assimilation, since the word trust

appears later in the

same paragraph. But that may just have been a coincidence. If you type truthiness in MS Word, sure enough

you're given trustiness as

the first suggestion (followed by trashiness,

frothiness, and trotlines, the last of which refers

to a type of fishing line).

We don't know if Glier and Stanley applied the

wayward spellcheckers themselves or if some intervening copy editor is

to blame. Either way,

this sort of spellchecking artifact is all too common these days, as

anyone who has had to slog through college term papers can attest.

Some of the substitutions are rather startling. Back in

1996, this example was noted

by a contributor to the Usenet newsgroup alt.usage.english:

This happened a few weeks ago to the menu of a well-to-do restaurant here in San Francisco. The menu was spell-checked, printed, and a copy displayed in the window of the restaurant (as is the custom here). Nobody noticed that the spell-checker turned "warmed spring salad greens with prosciuto" into "warmed spring salad greens with prostitutes."

I'm guessing that the restaurant menu actually had singular prostitute in place of the intended prosciutto (or prosciuto, if the writer missed the extra t) — amazingly enough, the custom dictionary in my copy of MS Word accompanying Office XP still doesn't recognize the spiced Italian ham and suggests prostitute instead. (There's a Sopranos joke in there somewhere.) Others have fallen prey to the same unfortunate replacement, as in this recipe appearing on a message board for Italian food:

Crumble bread sticks into a mixing bowl. Cover with warm water. Let soak for 2 to 3 minutes or until soft. Drain. Stir in prostitute, provolone, pine nuts, 1/4 cup oil, parsley, salt, and pepper. Set aside.

Some spellchecker artifacts only show up when

a particular typo is

made. In another case noted on alt.usage.english,

the misspelling of acquainted

as aquainted has caused some

spellcheckers to suggest aquatinted

instead. (That word, by the way, refers to etchings made using aquatint, a process that makes a print resemble a water color.) Thankfully, it appears that MS

Word has fixed this one, as aquatinted

now comes in second

place to acquainted in the

list of suggestions. But the damage has been done, as evidenced by

thousands of Googlehits.

(Another example of this kind showed up not too long ago on the Eggcorn

Database: amature, a

misspelling of amateur, is

often transformed by spellcheckers into armature.)

One very odd type of substitution started popping up a few years ago among users of Yahoo Mail. If an email in HTML format was sent to a Yahoo address and contained the string eval, it would mysteriously get changed to review when the message was received. So medieval became medireview, retrieval became retrireview, primeval became primreview, and so forth. (In French messages, the word for horse, cheval, would become chreview.) It turned out that eval was one of a number of strings that Yahoo's security filter automatically replaced in order to prevent cross-site scripting attacks. (Bizarrely, it also replaced mocha with espresso and expression with statement.) This was far more insidious than spellchecker substitutions, as the replacements were made automatically, without the user's knowledge. Yahoo eventually changed its security filter, but once again the Googlehits live on. Future generations will no doubt chuckle at our technologically medireview times.

[Update, 11/1/05: The Times has issued a correction for the truthiness/trustiness confusion. The spellchecker remained blameless.]

October 26, 2005

Preposition the circumstances

In my posting on "in terms of", I said in passing:

I was then moved to look at the frequency of "within the circumstances" -- more than I thought, but way less than the frequency of "in/under the circumstances" -- and to recall that I was taught in grade school that only "in the circumstances", and not "under the circumstances", was correct (because "circum-" means 'around'), which led me to look at MWDEU's informative and entertaining entry on "circumstances".

Here are the raw Google webhit figures:

in: 3,310,000

under: 3,980,000

The 16,200 figure is not to be sneezed at, but it's totally dwarfed by the others, which are 200-250 times as large. So far as I know, usage manuals do not yet complain about "within" in this context, but now that I've pointed out this minority option, maybe they soon will. Sigh.

As for "in" vs. "under": "under" is somewhat more frequent than "in", and the OED2's cites have "under" appearing before "in", but not enormously long before, so we'd conclude that the two prepositions are just stylistic options, with maybe a bit of an edge for "under". OED1 claims to see a meaning distinction between the two prepositions here -- 'mere situation' for "in" vs. 'action affected' for "under" -- and this claim was carried over into OED2, but few commentators now agree with it (or even understand it). It might be that the most important difference between the two is that "in" is normally unaccented, "under" accented. It certainly seems to be that some people tend to prefer one and some the other. But not much is known about the details of the choice between "in" and "under".

What makes the MWDEU entry so entertaining is the history of the proscription of "under the circumstances". First, it's an instance of a subtype of the Etymological Fallacy, which we here at Language Log Plaza comment on so frequently: the combinatory possibilities for "circumstances" are being dictated by the etymology of the word. Second, the proscription (with its EF underpinning) appears to have been a sheer invention, possibly by Walter Savage Landor in 1824. About a century after this, critics began to notice the issue, but for the most part allowed both prepositions. Nevertheless, the proscription of "under" would not die -- it's another zombie rule, this time one specifically not endorsed by Fowler (or, for that matter, Garner, who fancies himself Fowler's present-day heir) -- and it continues to surface every so often in people who passionately disapprove of "under the circumstances". I myself am a victim of this zombie rule: though I don't object to "under"-- I know too much about the facts to do that -- I use "in" almost exclusively, as far as I can tell, because that's what was ground into me in childhood. Another sigh.