August 31, 2005

Legislatively Challenged

Last week, according to a widely reproduced AP story, New York Governor George Pataki vetoed a bill that would have required the use of politically correct terminology in laws, regulations, and charters when referring to people with disabilities. Pataki said that he vetoed the bill because it established "vague and subjective" standards and observed that not only do preferences change over time but that people with the same disability disagree as to what terminology they prefer.

I'm afraid that I have to side with Governor Pataki on this one. The bill isn't about avoiding obviously and egregiously offensive terminology like gimp and crip. To my knowledge not a single New York law or regulation uses such terms. According to its sponsor, Harvey Weisenberg, the bill would have required the disabled to be called instead people with disabilities. Hunh? I see no relevant difference in meaning betwen the two. The main difference is that expressions like people with disabilities are longer and in many contexts will be more awkward and less readable. Yet another impediment to clarity and readability of laws and regulations is somethng we really do not need.

The bill also reflects the assumption of a form of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. Assemblyman Weisenberg is quoted as saying:

By using the correct language in legislation, New York state lawmakers can make a positive impact on how people with disabilities are perceived by society,

I doubt it. It could be true, but I find it striking that this and other similar ideas are put forward by serious people without a shred of evidence.

I have no idea what disabled people, and people with disabilities, think about this. Their thoughts on the matter, if any, are not mentioned in any of the news articles and do not turn up on casual Googling, but I know from my own experience that well-meaning people seem to come up with non-existant distinctions that mean nothing to those they are trying to benefit. An acquaintance once explained to me that he thought that one should never say that someone is a Jew, always that someone is Jewish. He thought that He is a Jew. is somehow offensive, while He is Jewish. is not. I don't know of any linguistic or grammatical principles from which this would follow, nor of even a smidgen of evidence that anyone else shares his perception. I certainly don't, and I am a Jew. That's how I put it. If anything, I prefer He is a Jew. to He is Jewish because I associate the latter usage, rightly or wrongly, with people who wrongly consider being Jewish to be purely a matter of religion, like being a Baptist or a Hindu.Leading questions and frickin' cooks

According to a CNN story about New Orleans mayor Ray Nagin's frustration over lack of coordination,

"There is way too many fricking ... cooks in the kitchen," Nagin said in a phone interview with WAPT-TV in Jackson, Mississippi, fuming over what he said were scuttled plans to plug a 200-yard breach near the 17th Street Canal, allowing Lake Pontchartrain to spill into the central business district.

Arnold Zwicky, who told me about this by email, wondered about three editorial differences between this textual version and what he remembered from hearing the clip on CNN TV news, which he rendered as

There's way too many frickin' -- excuse me -- cooks in the kitchen.

CNN has the clip on their website (if the link doesn't work, try going through the story linked above), so I was able to verify that Arnold's memory is exact. I've extracted just the cited phrase here.

The three differences, obviously, are

- un-contraction of there's to there is

- standardized spelling of frickin' as fricking

- elision of "excuse me"

With respect to the first and second points, Arnold was curious about whether his memory was wrong, or perhaps the Mayor was using informal language in a formal register. But Arnold's memory was exact, and I suppose that the partial formalization of the quote comes from a CNN copy editor, or an assumption by the writer that these are the right ways to render such things.

Opinions differ about how to transcribe informal speech. I tend to agree with the practice of writing -ing rather than -in', as Mark Twain did, though "fricking" in particular seems kind of silly. I feel that removing contractions is a bad idea, since in conversational English the lack of contraction in cases like this often indicates either some sort of emphasis or some extra dose of formality. In this case, the un-contraction is especially odd, since the singular is itself is non-standard. Still, Mark Twain himself did this, as in his maxim "The trouble ain't that there is too many fools, but that the lightning ain't distributed right".

Eliding the excuse serves to make a punchier quote, but a bigger issue is the extent to which the quote itself was set up by the interviewer. Here's the whole context:

| Ray Nagin: | Uh I'm a very impatient person, I would love to see those uh resources come a lot quicker, and I would love to see some of the chiefs that keep showing up down here to kind of stay away for a minute and let us get to- these implementations uh phases adequately done. |

| Interviewer: | Are- are there too many cooks in the kitchen, is that what I hear you saying, Mr. Mayor? |

| Ray Nagin: | Absolutely, in my opinion, there's way too many frickin' -- excuse me -- cooks in the kitchen, we had this implementation plan going, they should have done these uh sandbagging operations first thing this morning, and it didn't get done and I- quite frankly I'm very upset about it. |

This is the sort of ritual exchange that Rasheed Wallace lampooned here. It serves its purpose -- here we are, writing about Mayor Nagin's remarks, which took on a force that they would have lacked if the quote were just "I would love to see some of the chiefs that keep showing up down here to kind of stay away for a minute" or something similar.

Nagin apparently had good reason to be upset, and the reported helped him to express his anger in a way that got people's attention:

The National Weather Service reported a breach along the Industrial Canal levee at Tennessee Street, in southeast New Orleans, on Monday. Local reports later said the levee was overtopped, not breached, but the Corps of Engineers reported it Tuesday afternoon as having been breached.

But Nagin said a repair attempt was supposed to have been made Tuesday.

According to the mayor, Black Hawk helicopters were scheduled to pick up and drop massive 3,000-pound sandbags in the 17th Street Canal breach, but were diverted on rescue missions. Nagin said neglecting to fix the problem has set the city behind by at least a month.

"I had laid out like an eight-week to ten-week timeline where we could get the city back in semblance of order. It's probably been pushed back another four weeks as a result of this," Nagin said.

"That four weeks is going to stop all commerce in the city of New Orleans. It also impacts the nation, because no domestic oil production will happen in southeast Louisiana."

So it's easy to sympathize with what the reporter did: the conventions of the genre force him to make the point by asking the mayor a leading question, rather than expressing an opinion in his own voice.

[Update: Arnold Zwicky emailed

small additional subtlety on "there's" vs. "there is": "there is" + NPpl is indeed nonstandard (and somewhat more common in the south and south midlands than elsewhere, i believe -- i'm away from my sources on this today), but "there's" + NPpl should really be characterized, in current english, as merely informal/colloquial, rather than nonstandard. millions of people (like me) who wouldn't use "there is two people at the door" are entirely happy with "there's two people at the door". so the two versions differ not only in emphasis and/or formality, but also (for many of us) in standardness.

]

Killing me softly with their slides

Yesterday's Washington Post featured a column by Ruth Marcus entitled "Powerpoint: Killer App?" It begins with this very provocative first paragraph:

Did PowerPoint make the space shuttle crash? Could it doom another mission? Preposterous as this may sound, the ubiquitous Microsoft "presentation software" has twice been singled out for special criticism by task forces reviewing the space shuttle disaster.

The rest of the column is, as columns like these often are, equal parts funny and disturbing -- and each in several ways. I'm one of those sad folks who use Microsoft products like PowerPoint out of some ill-defined sense of necessity, and I'm always down for some Microsoft (product) bashing. However, I won't tolerate the gratuitous bashing of second-grade students' writing abilities nor that of those students' teachers' abilities to instruct them in writing.

I'm referring to this paragraph from the column, with emphasis added:

The most disturbing development in the world of PowerPoint is its migration to the schools -- like sex and drugs, at earlier and earlier ages. Now we have second-graders being tutored in PowerPoint. No matter that students who compose at the keyboard already spend more energy perfecting their fonts than polishing their sentences -- PowerPoint dispenses with the need to write any sentences at all. Perhaps the politicians who are so worked up about the ill effects of violent video games should turn their attention to PowerPoint instead.

Almost certainly, Marcus makes this claim in the absence of (a) any qualitative evidence of how "tutoring in PowerPoint" proceeds in second grade (was this vulnerable age group used simply for rhetorical effect?) or (b) any quantitative evidence of the ratio of time/"energy" that students spend "perfecting their fonts" vs. "polishing their sentences". Reading this criticism-founded-on-PTA-anecdote of both students and teachers has the bitter aftertaste of poor research on important issues -- I'm not saying the claims are false, only that I'm certain that they haven't been shown to be true in any significant way and that I don't see what good they do for any kids.

Though I do agree about the video games bit at the end of the above-quoted paragraph, at least when it comes to politicians. Leave the real work to the psychologists.

[Link to the column courtesy of Paul de Lacy.]

[

Update: John Lawler writes to tell me how well-worth reading Edward Tufte's piece "The Cognitive Style of PowerPoint" (cited by Marcus) is. I haven't spent the $7 to order it yet, but Marcus also cites a freely available story by Tufte that appeared Wired Magazine in 2003, "Powerpoint is Evil" ("Power corrupts. PowerPoint corrupts absolutely."), where Tufte mentions the use of PowerPoint in "elementary school":

Particularly disturbing is the adoption of the PowerPoint cognitive style in our schools. Rather than learning to write a report using sentences, children are being taught how to formulate client pitches and infomercials. Elementary school PowerPoint exercises (as seen in teacher guides and in student work posted on the Internet) typically consist of 10 to 20 words and a piece of clip art on each slide in a presentation of three to six slides -a total of perhaps 80 words (15 seconds of silent reading) for a week of work. Students would be better off if the schools simply closed down on those days and everyone went to the Exploratorium or wrote an illustrated essay explaining something.

I don't think I can accuse Tufte of not thoroughly researching this, but I would like to see more evidence (and will therefore probably fork over the 7$). for the references here to "teacher guides" and "student work posted on the Internet" -- this hardly seems like cause for this level of alarm, or for the conclusion that PowerPoint tutelage is somehow replacing "learning to write a report using sentences".

(Sidenote: Tufte's Wired story is accompanied by a somewhat different point of view on PowerPoint by David Byrne.)

Plus: Language Log's own Geoff Nunberg writes to remind me of his 1999 piece "Slides Rule" from Fortune Magazine, which also appeared in The Way We Talk Now, pp. 213-215.

]

[ Comments? ]

Google Purge

Last spring , Jean-Noël Jeanneney warned us about "cette inquiétude lancinante du n'importe quoi, de la dispersion du savoir en poudre" ("this throbbing anxiety for anything and everything, for scattering knowledge like dust"). Well, according to The Onion, here comes the vacuum cleaner: Google Purge.

"Our users want the world to be as simple, clean, and accessible as the Google home page itself," said Google CEO Eric Schmidt at a press conference held in their corporate offices. "Soon, it will be."

As John Battelle explains

"Thanks to Google Purge, you'll never have to worry that your search has missed some obscure book, because that book will no longer exist. And the same goes for movies, art, and music."

As a phonetician, I'm especially excited about Google Sound:

"Book burning is just the beginning," said Google co-founder Larry Page. "This fall, we'll unveil Google Sound, which will record and index all the noise on Earth. Is your baby sleeping soundly? Does your high-school sweetheart still talk about you? Google will have the answers."

Page added: "And thanks to Google Purge, anything our global microphone network can't pick up will be silenced by noise-cancellation machines in low-Earth orbit."

Finally, speech and language scientists will be able to do away with old-fashioned sampling methods, and rely instead on statistics calculated from the entire domain of phenomena under investigation! In fact, scholars and scientists of all types will be able to complete their transformation from field and lab-bench investigations to purely digital research:

Although Google executives are keeping many details about Google Purge under wraps, some analysts speculate that the categories of information Google will eventually index or destroy include handwritten correspondence, buried fossils, and private thoughts and feelings.

The company's new directive may explain its recent acquisition of Celera Genomics, the company that mapped the human genome, and its buildup of a vast army of laser-equipped robots.

I guess this is what Jean-Claude Juncker and other European politicians were talking about when they warned of "virulent attacks" on European culture, fearing that "Google's ambitious plans could result in important European literary works missing out and being lost to future generations". Did Jacques Chirac slip them classified reports from a DGSE mole in Mountain View?

I feel in honor bound to warn readers that the Onion is a satirical publication, and this post is a joke... However, I do think that there is a serious point to be made here. And it's not that there is a paranoid strain in European intellectual culture, or that Google's servers are the leading edge of the The Matrix.

For me, the lesson is a narrower one, directed at publishers in general, and scientific and scholarly publications in particular. There is growing evidence that Open Access increases impact. In my opinion, this effect is certain to increase, asymptotically approaching the point where publications that are not indexed and accessible on line will effectively cease to exist. No one will have to purge them -- they will have purged themselves.

[Onion link via Kerim Friedman]

New Orleans is essentially an arm of the Gulf of Mexico

So say Cornelia Dean and Andrew C. Revkin in today's NYT. After contributing to one of the disaster relief organizations, you might distract yourself up by taking a look at John Cowan's page of Essentialist Explanations. This is essentially a list of 736 sentences of the form <Language X> is essentially <Language Y> <produced under conditions Z>. Some are funny, some are silly, some are mildly offensive, some are nearly true.

A sample:

English is essentially Norse as spoken by a gang of French thugs.

English is essentially the works of Joyce with the hard bits taken out.

Swedish is essentially Norwegian spoken by Finns.

Danish is essentially Norwegian, only you drop out all the consonants, skip all the vowels and then mispronounce the rest.

Spanish is essentially Italian spoken by Arabs.

Francophones are essentially Germans speaking the bad Latin they were taught by Gauls.

French is essentially an attempt by the Dutch to speak a Romance language.

French is essentially a language that elides everything that doesn't get out of the way fast enough, and nasalises everything else.

Russian is essentially Punjabi that fell off the wagon. Contrariwise, Punjabi is essentially Russian with better spices.

Modern Greek is essentially Classical Greek as spoken by Venetians.

Mandarin is essentially Chinese as spoken by Mongols.

Encoding Puzzle Answer

Here's the solution to yesterday's encoding puzzle If you look at the HTML metadata, the page claims to be in ISO-8859-1 (aka Latin-1), an ASCII extension in which things like accented characters occupy codepoints above the ASCII range, while still remaining in a single byte. The claim, though technically true, is misleading. All of the characters are ASCII characters. That is, not a single byte on that page has a value greater than 0x7F. Technically, you can call that ISO-8859-1, since it is consistent with it, but really the page is in the ASCII subset of ISO-8859-1.

Inspection of the page source reveals that the accented letters are each represented by a sequence of two HTML decimal numeric character entities. For example, é e with acute accent, is not represented by the single byte with value 0xE9 as it would be in ISO-8859-1. Rather, it is represented by a sequence of twelve bytes: é. à is an HTML representation for à upper case a with tilde; © is an HTML representation for © copyright symbol. That's why the word représente comes out as représente on your terminal. (Don't anybody write in to say that this is the usual spelling used by dyslexic speakers of North African French when text-messaging after they've had a few drinks or something like that. Writing Unix man pages is a serious, indeed sacred, matter. Learned authors have compared the interpretation of Unix man pages to the study of the Talmud.)

What do I mean by saying that à is an HTML representation of à and that © is an HTML representation of ©? In HTML, characters may be represented as many as four ways:

- They may be directly encoded. For example, a byte with the numerical value 0x26 (38 to the hexadecimally challenged) is the ASCII code, and therefore also the ISO-8859-1 and Unicode, for the ampersand character &. Most of the text that you see on web pages is represented this way.

- They may be represented by character references. These are little labels enclosed between an ampersand and a semi-colon. For example, ampersand may be represented &. Such character references exist for most of the common symbols, such as © and ®, and for letters with diacritics, such as é and à. (You may be wondering how it is that I am writing things containing & if it is used to introduce character references. The answer is that I am very clever. If that doesn't satisfy you, the view page source command in your browser should clue you in.)

- Characters may be represented by means of hexadecimal numeric character entities. A numeric character entity begins with an ampersand and a cross-hatch and ends with a semi-colon. Between them is a numerical representation of the character's Unicode value. If the number is base 16, it is preceded by an x. The hexadecimal numeric character entity for ampersand is &.

- Characters may be represented by decimal numeric character entities. These are just like hexadecimal numeric character entities except that the number is in base 10. That it is decimal is marked by omission of the x that marks hexadecimal numbers. Ampersand is represented as a decimal numeric character entity as  . No one knows for sure why decimal numeric character entities exist since they are wholly redundant and not nearly as elegant as their hexadecimal counterparts. Some scholars suspect that they have a symbological value. Perhaps a sequel to The Da Vinci Code will enlighten us.

So, how did é end up represented as é? Well, é is an ASCII-fied representation of a sequence of bytes whose numerical values are 0xC3 (aka 195) and 0xA9 (aka 169). Notice how the use of decimal numeric character entities obscures things. It just happens that 0xC3 0xA9 is the UTF-8 encoding of UTF-32 0xE9. In its pure and ethereal form, Unicode codepoints are all 32 bits, or 4 bytes. For various reasons (discussed previously on Language Log and in more detail here) the preferred form for exchange of Unicode-encoded text is UTF-8, in which most characters are encoded as two or more bytes.

To pull all this together, the garbled man pages are what you would get if you started off with a page in UTF-8, and mistakenly thinking that it was in ISO-8859-1 ran it through an HTML-izer that converted anything outside the ASCII range to numeric character entities.

The reason for using an HTML-izer is that some software, such as the software that runs this blog, cannot handle bytes whose high bit is set. If you enter such a byte into a Language Log entry, it looks fine when you enter it, but you will find the post truncated immediately before the first such byte. So if you want to use non-ASCII characters with confidence in web pages, it is wise to convert them all to character entities. I have written a couple of programs that do this myself.

Several of our readers figured this out: Diane Bruce responded in the wee hours of last night not long after I posted the puzzle. The others are Aaron Elkiss and John O'Neill.

August 30, 2005

An Encoding Puzzle

Recently I looked something up in the GNU/Linux manual pages at http://maconlinux.net/linux-man-pages/fr/strtol.3.html, which are in French. and couldn't get them to display correctly. Most of the text came out fine, but accented letters, and generally anything outside the ASCII range, came out garbled. At first I thought that the browser might be displaying the page using the wrong encoding, but changing encodings didn't solve the problem. The Spanish manual pages at http://maconlinux.net/linux-man-pages/es/strtol.3.html exhibit the same problem.

[Note: when I checked these URLs just now, I got a server error. If it is still acting up, here's a link to the Google cache of the French page.]

Although I couldn't get these pages to display correctly, short of writing a little script to transform them before letting the browser at them, after a few minutes I figured out what had happened to them. There is a perfectly straightforward explanation for what happened to them. For now, I'm going to leave the solution as an exercise for the ling-technically inclined reader. I'll post it tomorrow.

"Grammar cranks" of the right

[Guest post by Benjamin Zimmer] Linguistic persnicketiness is certainly not restricted to any particular political ideology. But prescriptivist gripes are sometimes grounded in a conservative distaste for loosey-goosey moral relativism and the like. Here are two defenders of language conventions hailing from the political right: one a comic-strip character and one the current Supreme Court nominee.

The first example is Bruce Tinsley's comic strip Mallard Fillmore, marketed as a conservative answer to such left-leaning fare as Doonesbury and The Boondocks. Tinsley describes his protagonist (who bears a striking resemblance to Daffy Duck) as "a seasoned, rumpled ex-newspaper reporter" who "thinks we average, hardworking Americans need a break instead of a lecture." On Sunday, however, Mallard apparently thought we average, hardworking Americans needed a lecture after all (albeit in rhyme): a punctuation rant in the manner of Lynne Truss.

Mallard must have been reading Truss's best-seller, Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation, since he echoes her impassioned plea, "How much more abuse must the apostrophe endure?" But Truss never states a black-and-white rule that apostrophes are only used "when you leave a letter out, or if you want to show possession." There are plenty of exceptions, such as the use of apostrophes in the pluralization of letters (e.g., "mind your p's and q's") or the pluralization of words used citationally (e.g., "the's and a's are reduced before consonants").

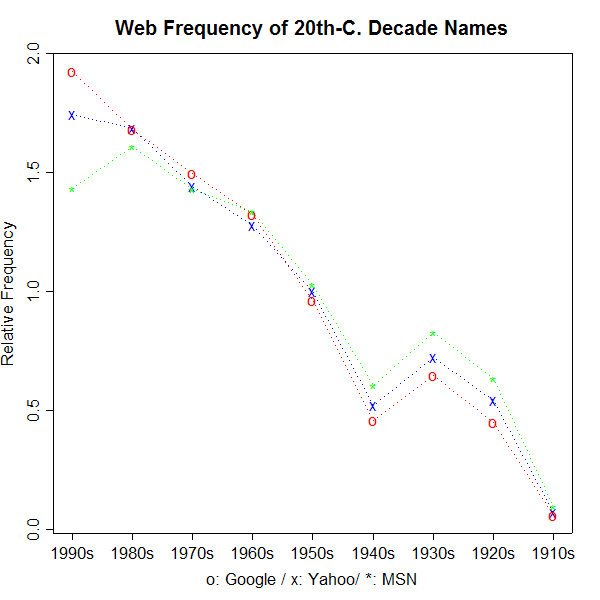

Mallard's examples of rampant apostrophization not surprisingly include the much-maligned greengrocer's apostrophe ("fresh apple's"), along with extraneous apostrophes in decade names ("the 80's") and pluralized family names ("the Smith's"). But as "a seasoned, rumpled ex-newspaper reporter," Mallard should know that the jury's still out on apostrophizing decade names. The New York Times house style, for instance, keeps the apostrophe in for names of decades; a search on the Times archive finds five examples of "the 80's" in Sunday's paper alone. On the other hand, given his usual tirades against the liberal domination of the media, Mallard might simply take this as an indication that the bastion of the MSM is too weak-kneed and morally relativistic to enforce proper rules of punctuation.

Rush, the little boy in the strip, warns Mallard that he's "turning into one of those grumpy old grammar cranks." (Linguists have grown accustomed to seeing "grammar" used as a catch-all term to encompass any number of perceived linguistic conventions, from punctuation to usage to pronunciation, depending on the pet peeves of the writer.) As it happens, the apostrophe-abusing New York Times had an article on Monday about a grumpy young grammar crank in the 80s (or the 80's), one who would later in life be nominated to become a Supreme Court justice. Under the headline "In Re Grammar, Roberts's Stance Is Crystal Clear," Anne Kornblut approaches the recently released Reagan-era memos of John Roberts with an eye towards his "tendencies as a grammarian." Roberts, we learn, "frequently peppered notes and documents with minor syntax corrections even when the basic legal arguments w ere sound." Some of his corrections really did have to do with grammar or syntax, such as his insistence on maintaining consistent parallel structure and pronominal reference. Other cases noted by Kornblut simply indicate a pickiness regarding word choice, such as Roberts's preference for voluntarism over volunteerism, ensuring over insuring, and multilateral over plurilateral. (We would need to see the context of these memos to know what beefs Roberts might have had with the offending words.)

Roberts also took issue with the phrasing of Neil Armstrong's famous line when setting foot on the moon (which was to be quoted by his boss, White House counsel Fred F. Fielding, in remarks at a Kennedy Space Center picnic):

"It is my recollection," Mr. Roberts wrote, "that he actually said 'one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind,' but the 'a' was somewhat garbled in transmission. Without the 'a,' the phrase makes no sense."

Roberts is right that the phrase makes no sense without the "a", but he should take it up with Armstrong himself. The line wasn't actually "garbled in transmission" — Armstrong flubbed it, as the Snopes urban legends website has documented.

Kornblut writes, "If Judge Roberts is confirmed, and his word-consciousness follows him to the court, it will put him in the upper tier of justices who have put a premium on the English language." It's difficult to tell from the analysis of the memos if Roberts's "word-consciousness" will rise above the level of mere curmudgeonliness. But one auspicious omen appears in the graphic sidebar accompanying the article. In a memo from 1983, Roberts complains about how newspaper columnists focused on Ronald Reagan's memorable use of the word keister:

"Frankly, I've had it up to my keister with newspaper columns about an expression fairly common to those of us reared in the Midwest. I have drafted a reply." He concluded: "It is interesting how familiarity with slang phrases often varies among different parts of our country. In this case, excuse the bad pun, but I suppose it may depend on where one was reared."

Roberts makes a rather obvious dialectological point, but it's one that is frequently lost on self-appointed guardians of good "grammar". I take this as a hopeful sign that Roberts is no strict constructionist when it comes to linguistic variation.

[Update (by Mark Liberman): Bez Thomas, among others, reminded us of a classic apostrophe rant in cartoon form, from the left end of the political spectrum:

Both from the right and from the left, (some of) these defenses of linguistic norms are notable for their moral and emotional fervor. As reported in the NYT, Judge Robert's linguistic strictures are rather even-tempered in comparison.]

August 29, 2005

Encounters with Silliness

I've been catching up on Language Log and various other things. Mark's post about silly things people say about linguistics reminded me of a visit I had from a student some years ago when I was teaching at the University of Northern British Columbia. She came to discuss with me the topic on which she wanted to write her term paper for someone else's course, namely her idea that the Gitksan-Witsuwit'en are the Lost Tribes of Israel.

I began by objecting to the idea that the Gitkwan-Witsuwit'en could be the Lost Tribes of anywhere, on the grounds that they aren't a unitary group at all. The Gitksan speak a Tsimshianic language, closely related to Nisga'a, whereas the Witsuwit'en speak an entirely different Athabaskan language, whose closest relative is Carrier, which I have mentioned here from time to time. Their languages are no more similar to each other than English and Navajo. The reason that the term Gitksan-Witsuwit'en exists is that the two were for a time allied for political and legal purposes in the form of the Office of the Gitksan-Witsuwit'en Hereditary Chiefs. This is the organization behind Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, the lawsuit that ultimately led the Supreme Court of Canada, in 1997, to rule that aboriginal title still exists in British Columbia as a burden on the title of the Crown. The fact that these two quite different groups formed an alliance no more means that they shared a common history than does the fact that Turkey and Germany were allied in the First World War. We do not draw from this fact the inference that there is a Turco-Germanic people.

In addition to pointing out, with no evident impact, the fact that there is no such tribe as the Gitksan-Witsuwit'en, I enquired as to what precisely the evidence was, in her view, that the Gitkwan-Witsuwit'en were the Lost Tribes of Israel. I was pretty certain that they were not mentioned in the Bible. Was there some other evidence she had in mind?

She immediately demanded to know whether I believed in the Bible. I responded that my view of the truth of the Bible was irrelevant since the Bible had nothing to say about the matter. We went back and forth on this briefly. Then she stalked off, convinced that I was yet another unbeliever whose denial of the truth of the Bible led him to reject her hypothesis about the Gitksan-Witsuwit'en. There's no point in arguing with some people.

Scammers' Language

I just got the following email message:

Dear user of babel.ling.upenn.edu, mail system administrator of babel.ling.upenn.edu would like to inform you that, We have found that your account was used to send a huge amount of spam messages during the recent week. Most likely your computer had been infected and now contains a trojan proxy server. We recommend you to follow our instruction in order to keep your computer safe. Best regards, babel.ling.upenn.edu user support team.

It is accompanied by a zip file putatively containing the instructions that I am supposed to follow. I imagine that it actually contains a virus, though I'm not going to go to the trouble of finding out. (This is the one downside to running GNU/Linux - if I actually want to try out a virus I have to go find a machine running Microsoft Windows. I feel so left out...)

Anyhow, any native speaker of English will detect a number of errors in the above message, some of them errors or deviations from standard written usage of the sort that a native speaker is not likely to make at all, or even a non-native speaker who has been here long enough to be working as a system administrator. There's the use of a comma at the end of the salutation in place of a colon, the failure to start the first sentence on a new line, the failure to capitalize the first letter of the first word of the new sentence, and the omission of the before mail. Then there is the use of a comma rather than a colon before something set off like a quotation or list entry and the incorrect treatment of a subordinate clause as such. A native speaker would not say recent week instead of past week, or had been infected instead of has been infected. The construction We recommend you to follow... is not English.

Such a plethora of errors should alert just about anyone that the message is a fake. Are the scammers so foolish or ignorant that they don't realize this? It probably wouldn't be too hard to get someone to polish their prose. Or are enough computer users too dense to realize that messages like this are fake that the scammers don't bother?

The modish macron

Now joining the heavy metal umlaut is, apparently, the modish macron. To the right is a picture of the awning sign of a local hair place, VŌG. I walk past it frequently, wondering who's supposed to be attracted by evocations of Vogon style, but I didn't realize it was part of a trend. Recently, Phillip Jennings wrote in with news of "a new downtown Minneapolis salon named all-caps-something-or-other BLŪ", and also a magazine called "Modern HŌM". I can't find any web presence for either of these, but I'll take Phillip's word for it.

Now joining the heavy metal umlaut is, apparently, the modish macron. To the right is a picture of the awning sign of a local hair place, VŌG. I walk past it frequently, wondering who's supposed to be attracted by evocations of Vogon style, but I didn't realize it was part of a trend. Recently, Phillip Jennings wrote in with news of "a new downtown Minneapolis salon named all-caps-something-or-other BLŪ", and also a magazine called "Modern HŌM". I can't find any web presence for either of these, but I'll take Phillip's word for it.

If you know of any other examples, send them along. Extra points for cases that don't involve back vowels or capital letters.

This usage apparently imitates the conventions of pronunciation fields in (some) American dictionaries, rather than from the sort of diacritical associations involved in the heavy metal umlaut, or the more general allure of foreign branding. This may be related to Qwest's belief that badly faked dictionary pronunciations are authoritative. However, I imagine that the real motivation is the difficulty (both legal and psychological) of establishing a brand around common words like vogue or home.

Unfortunately, the modish macron doesn't help our campaign to promote the IPA through popular culture.

[Update: Jesse Sheidlower points out PŪR, and mentions

[Update: Jesse Sheidlower points out PŪR, and mentions

"another one I'm thinking of, that I can't quite place, that so irritates me that I deliberately mispronounce it because I feel so manipulated by the macron".

Marilyn Tarnowski points out the Sprint WordTraveler FŌNCARD.

Eric Bakovic writes that

I used to laugh at a commercial from the (early? mid?) '80s for a shampoo called FOHO ('For Oily Hair Only'), but a quick google search fails to confirm my possibly wrong memory that both Os had macrons over them. But this doesn't really disconfirm my memory either; the product's been (predictably) discontinued, and the few hits I got only had ASCII-text examples, no images of the labels or anything like that. I did discover that it used to be a Gillette product, but that's about it.

Aaron Dinkin writes that

I seem to remember that there was a brand of juice box called "Boku" - macrons over the O and the U, and it was pronounced "beaucoup".

More information about BŌKŪ can be found here .

And Chris Waigl gets extra points for reminding me of her

2/8/2005 post on IPA and exoticism, which includes the example of séxūal, with a lower-case u macron.]

And Chris Waigl gets extra points for reminding me of her

2/8/2005 post on IPA and exoticism, which includes the example of séxūal, with a lower-case u macron.]

[Update #2: David Low was the first of several readers to point out that in Episode 9F22 of The Simpsons, Sideshow Bob is shown with LUV and HĀT on his knuckles (like other characters on that show, he has just three fingers plus a thumb on each hand). This seems less like a "modish" macron and more like a creative way to update an old movie reference (picture here) for consistency with a cartoon anatomical convention.]

[Update #3: David Doherty also gets extra points for the lower-case o with macron in the

Seattle nightspot TōST. ]

[Update #3: David Doherty also gets extra points for the lower-case o with macron in the

Seattle nightspot TōST. ]

[Update #4: Ed Keer at Watch Me Sleep

pointed out that the board game Hūsker Dū uses macrons, which the rock band Hüsker Dü changed into heavy metal umlauts; according to the

wikipedia entry, "The name of the game is spelled with macrons to emulate Scandinavian letters with macrons over them (even if macrons are only used in hand-written text)", and the game was originally published that way in Sweden in the 1950s, so if there's any connection to the new VŌG for macrons, it can only be because of some childhood experience of today's marketeers.]

[Update #4: Ed Keer at Watch Me Sleep

pointed out that the board game Hūsker Dū uses macrons, which the rock band Hüsker Dü changed into heavy metal umlauts; according to the

wikipedia entry, "The name of the game is spelled with macrons to emulate Scandinavian letters with macrons over them (even if macrons are only used in hand-written text)", and the game was originally published that way in Sweden in the 1950s, so if there's any connection to the new VŌG for macrons, it can only be because of some childhood experience of today's marketeers.]

[Update #5: Rebekka Puderbaugh mailed in a link to

Zōe's Flax & Soy products.]

[Update #5: Rebekka Puderbaugh mailed in a link to

Zōe's Flax & Soy products.]

[And reported by Andrew Malcovsky, the

PAYDĀTA company in Vermont...]

[And reported by Andrew Malcovsky, the

PAYDĀTA company in Vermont...]

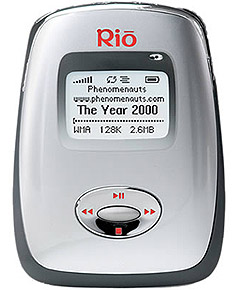

[And here's another example, the Riō mp3 player, submitted by Kilian Hekhuis:

]

[And another:

Cepacol, submitted by Mark Wayne:

]

Never mind the storm surge, watch out for those toponyms

In the midst of the disaster, some people are still worried about usage and pronunciation:

When this is over, someone please tell Tucker Carlson and the other national newscasters that "St. Louis" is in Missouri, and we call our town "Bay St. Louis". Hope they don't try to pronounce Pascagoula, Gautier, or Delisle.

Here's hoping that Tucker Carlson's misrendering of toponymic shibboleths is the worst damage they suffer.

August 28, 2005

Which It's Happy Bunny are you?

But actually, it's not Happy Bunny, it's It's Happy Bunny, even in subject position: "Does It's Happy Bunny dislike Boys?? Of course not. It's Happy Bunny dislikes everybody." Likewise after which, as in the numerous "which IT'S HAPPY BUNNY are you?" quizzes.

Joanne Jacobs reports that

Some blunt-spoken Happy Bunny messages, including "You're ugly and that's sad" and "It's cute how stupid you are," wouldn't make the cut at Highland Park High School.

"We consider that harassment, and we just don't allow it," Principal Jack Lorenz said.

Thought the target demographic is very different, this reminds me of the BOFH phenomenon -- both BOFH and IHB involve openly flaunting well known but traditionally covert hostility.

IHB slogans like "I think I gave you crabs" hint that the original It's Happy Bunny target might have been a bit older and more cynical than the group that has responded is. And indeed this article quotes IHB's inventor, Jim Benton, confirming this:

When Benton originated It's Happy Bunny, he expected the products bearing his artwork -- including a handful containing anti-boy phrases -- to appeal to young women ages 16 to 26. "It actually turned out to be much broader in appeal than we thought," he says. In the Bay Area, for instance, It's Happy Bunny can be found in shopping malls at Claire's, a nationwide retail chain that targets its accessories to girls ages 7 to 12.

IHB's role in validating adolescent female hostility is none of our business here. Instead, I want to make a linguistic point -- phrasal names like It's Happy Bunny introduce into English, in a small way, the phrasal names that are dominant features of many other cultures and languages. The most common source for this kind of thing in English has been bands whose names are sentences like They Might Be Giants or Frankie Goes to Hollywood. The ease with which such phrasal names enter general use seems to show that the difference in this respect between English and (for example) Yoruba is more a matter of general cultural choice than of linguistic structure.

[As far as I know, IHB consumers are all female, but there seems to be some uncertainty about the gender of the bunny itself.]

'Tis the gift to be simplistic

"Refreshingly simplistic," was how a VH1 reviewer described a new CD by some artist whose name I didn't recognize. I couldn't jot it down, since I was wheezing on a treadmill at the time, but a Google search turns up 425 instances of the phrase, with results that are variously comical and bizarre. A Web design company boasts that its work is "stylish and refreshingly simplistic." SunMex Vacations tells vacationers that "most of Mazatlan remains refreshingly simplistic." And an Amazon.com customer review of Nelson Goodman's classic Fact, Fiction, and Forecast says, "The way that Goodman perceives our inductive system is unique and refreshingly simplistic." The press isn't immune, either -- the phrase is rare there, but it turns up in a 1996 article in Billboard and a 1998 article in The Independent.

A familiar sort of malaprop, but there's a bit more going on here.

That analysis of simplistic as merely a fancy synonym for simple seems to be implicit in the word oversimplistic. If you accept Merriam-Webster's definition of simplistic as "oversimple," then oversimplistic would be a pleonasm. Yet the word gets more than 14,000 Google hits and appears in 178 stories in Nexis major newspapers (the earliest cite I've found is from a 1970 story in The New York Times, but this would probably be easy to antedate). In fact Merriam-Webster's gives oversimplistic as a run-in in the entry for the prefix over-, and while the OED doesn't list oversimplistic as a word, the editors actually use it in their definition for nothing-but-ism: "An oversimplistic approach to the explanation of a phenomenon, which excludes complicating factors; reductionism."

You could argue, of course, that the over- of oversimplistic is chiefly an intensifier, the way it is in items like overbrutal, overfacile, overfussy, and overhasty, in all of which the root itself carries an implication of excess. But the existence of phrases like "refreshingly simplistic" shows that for some people, at least, simplistic itself has acquired a purely positive meaning. My guess is that this development is helped along by an analogy with simplicity. Someone looking for an adjectival version of "refreshing simplicity" (6290 Google hits) might be drawn to "refreshingly simplistic," particularly given the effective absence of the intermediate forms simplism and simplist that words ending in -istic tend to imply. (The words actually exist, but are rare and recondite.)

August 27, 2005

Disowning The Brothers Grimm

No, I don't want to disown Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm, the first of whom is something of a hero of historical linguistics. I want to disown the movie The Brothers Grimm, and I'm doing this on behalf of linguists everywhere.

What the movie has in common with the real world is: two brothers named Grimm, early-19th-century Germans who were involved with fairy tales. As far as I can tell, that's it. Imagine a Life of Noam in which, through the miracle of miniaturization, the heroic Chomsky (played by Brad Pitt in a revealing latex bodysuit) takes a band of brawling adventurers into the deepest recesses of the human brain, to recover bits of the language organ for sale through his start-up company -- a sort of cerebral 21st-century Fantastic Voyage. Appalling.

In any case, not a movie to put on the recommended viewing list for students in your intro linguistics classes.

[Update, 8/30/05: Correspondents have now suggested two alternative scenarios. First, from Andrew Malcovsky, on his blog, a proposal that sticks much more closely to the historical facts than Terry Gilliam did, yielding something that might be entitled The True Adventures of Will and Jake.

And then from Tim Fitzgerald, who finds my Brothers Grimm/Chomsky comparison unfair (since "these two men have been chosen for their role in storytelling"), a counterproposal for "a much more apt comparison":

... 200 years from now a movie (or whatever form of mass entertainment they may use) on Spielberg's harrowing attempt to fight off dinosaurs from the Temple of Doom with the help of his loving extra-terrestrial friend.

Ah, California Spielberg and the E-Temple of Doom. Please, don't write to tell me that Steven Spielberg was born in Cincinnati, Ohio. I know that. But he belongs, truly belongs, to California].

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

No more inveigling in California courts

No more inveigling in California courts, according to a story by AP legal affairs writer David Kravets that appeared on 8/25/05 in the San Francisco Chronicle:

When California jurors sit on kidnapping cases, judges will no longer be required to explain that the perpetrator had to "inveigle" his victim.

Instead, as part of an eight-year effort to simplify jury instructions, the judge may say it like it is -- "enticed" his victim.

The new guidelines also revise the characterizations of (among others) "reasonable doubt" and "mitigation" and, in a move objected to by many prosecutors, has them referred to as "prosecutors" rather than as "the people". Though the changes are modest (intentionally so, according to lawyer-linguist Peter Tiersma, who helped craft them), some judges maintain that they "dumb down the justice process", an accusation that would be hard to make stick on the basis of the examples Kravets provides; "entice" for "inveigle", for instance, is scarcely a giant step away from judicial clarity and towards street speech.

A Google web search gives ca. 74,800 hits for "inveigle" in its various forms, vs. ca. 4,740,000 for "entice" in its various forms, so "inveigle" seems to be enormously less frequent -- less familiar -- than "entice". The disparity is much greater than this, though, since a huge number of the "inveigle" hits are mentions rather than uses -- they're from discussions of the meaning of "inveigle", including as a legal term -- and many more are uses in specifically legal contexts. Not that "inveigle" lacks ordinary-language uses; consider "He had slyly inveigled her up to his flat / To view his collection of stamps" (Flanders and Swann, "Have Some Madeira, M'Dear") and many everyday occurrences like these:

... as per usual, was one poor SOB trying to inveigle shoppers into buying ... (Leah Garchik, "The In Crowd" Column, San Francisco Chronicle, April 14)

inveigle yourself into the homes and wineries of a few big names whose

egos ...

(link)

Still, "entice" is probably a small improvement on "inveigle".

The changes seem to be mostly in vocabulary. For instance, the old version defines "mitigation" as

any fact, condition or event which does not constitute a justification or excuse for the crime in question, but may be considered as an extenuating circumstance in determining the appropriateness of the death penalty

which is now

any fact, condition, or event that makes the death penalty less appropriate as a punishment, even though it does not legally justify an excuse for the crime

This maintains the two-clause syntax, with coordination replaced by subordination, and it reverses the order of the proviso (about not justifying the crime) and the main part of the definition (about allowing certain factors to be taken into account), in favor of putting the main part first, which is surely an improvement. It also reduces the nominalization quotient a bit, by replacing "justification" by "justify" and "appropriateness" by "appropriate". And it replaces the restrictive relativizer "which" by "that", which could be seen as either as a move towards informal English or as a move towards prescriptively standard English, depending on who you read.

But mostly what it tries to do is unpack the meaning of the term of art "extenuating circumstance".

Another change tries to unpack "innocent misrecollection", also a term of art (ca. 447 Google webhits, all of them apparently in legal contexts), via replacing

Innocent misrecollection is not uncommon.

by

People sometimes honestly forget things or make mistakes about what they remember.

More side-by-side comparisons in Kravets's article.

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

"Approximate" quotations can undermine readers' trust in The Times

So says the NYT code of ethics, as well it should. For the past couple of months, I've been muttering about sloppy if not dishonest quoting practices in print media, including at the NYT. There's a particularly striking example in an 8/18/2005 article by Joel Brinkley and Steven R. Weisman, based on an interview with Condi Rice, which ran under the headline "Rice Urges Israel and Palestinians to Sustain Momentum".

The NYT article starts like this:

Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice on Wednesday offered sympathy for the Israeli settlers who are being removed from their homes in Gaza but also made it clear that she expected Israel and the Palestinians to take further steps in short order toward the creation of a Palestinian state.

"Everyone empathizes with what the Israelis are facing," Ms. Rice said in an interview. But she added, "It cannot be Gaza only."

The transcript of the interview was posted by the U.S. State Department web site under the title "Interview With The New York Times", dated August 17, 2005. In that transcript, the only occurrence of the string "empathize" is this one:

I know, in having talked to them and watched how hard and I think everybody empathizes with what every Israeli has to be feeling and with people uprooting from homes that they have been in for a generation and the difficulty and the pain that that causes.

And the only place where "Gaza only" occurs is here:

The other thing is, just to close off this question, the question has been put repeatedly to the Israelis and to us that it cannot be Gaza only and everybody says no, it cannot be Gaza only.

In between those two sentences are more than 1,300 words and 20 conversational turns.

Taking the first "quote" first, and ignoring the problem of yanking a phrase out of context, we've got an "approximate quotation" by anyone's standards (State Department transcript in black, NYT quote in blue):

Everyone empathizes with what the Israelis are facing

... and I think everybody empathizes with what every Israeli has to be feeling and ...

On the construal most favorable to the NYT -- scoring only the fragment from "everybody" to "feeling", and giving maximum credit for substitutions instead of insertions and deletions -- we have 5 substitutions and 2 deletions relative to 10 original words, for a word error rate of 70%. The meaning is similar, but that makes it a paraphrase rather than a quote.

In the case of the second quoted fragment, which Secretary Rice is said to have "added", there are three obvious problems. First, it's wrong to take a clause out of an indirect quotation and pretend that it's direct speech. If you say "everybody tells me that X", I can't quote you as asserting X -- you might well go to add "but I don't believe it for a minute". In this case, Rice does seem to include herself among the "everybody" who says that "it cannot be Gaza only", but that brings us to the second problem: she goes on to explain what she (at least) means by "not Gaza only", and it's not very much. Specifically,

There is, after all, even a link to the West Bank and the four settlements that are going to be dismantled in the West Bank. Everybody, I believe, understands that what we're trying to do is to create momentum toward reenergizing the roadmap and through that momentum toward the eventual establishment of a Palestinian state.

And finally, the linking phrase "but she added" seems to me to be the most dishonest thing of all. The meaning of add in question is something like "to say or write further", with the implication that the addition is in immediate rhetorical contiguity with what is added to. The use in Brinkley and Weisman's third sentence carries the clear implication that Rice chose to extend her remarks about empathy for the Gaza evacuation with a contrasting reminder of the need for further Israeli territorial concessions.

Now, that's the NYT's editorial line, and it might be the right line to take, but it's not really what Rice said. Not only was her "addition" yanked out of indirect speech attributed to others, not only was it was hedged immediately by a reference to the four West Bank settlements already being evacuated and a vague commitment to "momentum towards reenergizing the roadmap", but most important, it was in response to a different question, roughly eight minutes later, following 9 other intervening questions and answers.

I surmise that Brinkley and Weisman (or their editor) wrote the lede based on what they wanted to project as Rice's intent, and then looked through their notes on the interview for an illustrative quote. Not finding one, they stitched something together out of widely-separated fragments taken out of context. Somehow it's more surprising to see this done to the U.S. Secretary of State than to the San Antonio Spurs' scoring leader . But whether the speaker is Tim Duncan or Condi Rice, we should be able to believe that words in quotation marks in a newspaper stories are an accurate reflection of what was said, and give a fair impression of what was meant.

This is not just my own opinion. I've previously cited the NYT's own code of ethics on quotations:

Readers should be able to assume that every word between quotation marks is what the speaker or writer said. The Times does not "clean up" quotations. If a subject’s grammar or taste is unsuitable, quotation marks should be removed and the awkward passage paraphrased. Unless the writer has detailed notes or a recording, it is usually wise to paraphrase long comments, since they may turn up worded differently on television or in other publications. "Approximate" quotations can undermine readers’ trust in The Times.

The writer should, of course, omit extraneous syllables like "um" and may judiciously delete false starts. If any further omission is necessary, close the quotation, insert new attribution and begin another quotation. (The Times does adjust spelling, punctuation, capitalization and abbreviations within a quotation for consistent style.) Detailed guidance is in the stylebook entry headed "quotations." In every case, writer and editor must both be satisfied that the intent of the subject has been preserved.

Assuming that the State Department's transcript is accurate, the Brinkley and Weisman article seems to be a clear violation of both the letter and the spirit of this policy. Unfortunately, such violations are the norm rather than the exception, not only at the NYT but in print media in general.

Ultima Toolies

I'm used to noticing new things in old books, usually descriptions or situations or emotions that went past me before but now catch my attention for some reason. Last night I was surprised to learn a new word from a book that I've read at least once before: Ross Macdonald's Black Money, originally published in 1965.

Lew Archer has tracked Leo and Kitty Ketchel from LA to a mansion in "Santa Teresa", Macdonald's alias for Santa Barbara. Kitty is speaking. Lew, as usual, is thinking.

"Leo made a lifetime of enemies. If they knew he was helpless, his life wouldn't be worth that." She snapped her fingers. "Neither would mine. Why do you think we're hiding out in the tules here?"

To her, I thought, the tules meant any place that wasn't on the Chicago-Vegas-Hollywood axis.

[p. 189, 1990 Warner paperback edition]

When I hit that passage, I had absolutely no memory of ever having seen or heard the word tule, in that book or anywhere else.

The OED says that tule refers to

Either of two species of bulrush (Scirpus lacustris var. occidentalis, and S. Tatora) abundant in low lands along riversides in California; hence, a thicket of this, or a flat tract of land in which it grows.

and gives citations back to 1837

1837 P. L. EDWARDS Jrnl. 20 July (1932) 26 Driving her along the margin of a bulrush or Tule pond she turned about.

1845 J. C. FRÉMONT Rep. Exploring Expedition 252 They..live principally on acorns and roots of the tulé, of which also their huts are made.

1850 W. R. RYAN Personal Adv. Upper & Lower Calif. I. 298 The Indians of the party were despatched to hunt up the banks of the river for toolies.

The etymology is given as

[ad. Aztec tullin, the final n being dropped by the Spaniards as in Guatemala, Jalapa, etc.]

and the pronunciation is as suggested by the alternative spelling toolies.

The AHD entry explains further that

Low, swampy land is tules or tule land in the parlance of northern California. When the Spanish colonized Mexico and Central America, they borrowed from the native inhabitants the Nahuatl word tollin, “bulrush.” The English-speaking settlers of the West in turn borrowed the Spanish word tule to refer to certain varieties of bulrushes native to California. Eventually the meaning of the word was extended to the marshy land where the bulrushes grew.

Merriam-Webster's Unabridged has similar information, as does Encarta, which adds that "to be in deep tules" is a Hispanic expression meaning "to be in trouble with the law".

The OED has toolies, glossed as "Backwoods; remote or thinly populated regions.", with citations back to 1961 -- but curiously, flags it as a Canadian regional term rather than a Californian one:

1961 R. P. HOBSON Rancher takes Wife i. 22 We're plenty far back in the toolies at Batnuni.

Kenneth Millar (who wrote as Ross Macdonald) was born in Los Gatos but educated in Canada, for what that's worth.

Among the dictionaries I checked, none besides the OED gives tules, under any spelling, the meaning that's apparent in the Black Money passage. And glancing through the first hundred Google hits for {"in the tules"} didn't turn up any similar figurative uses, except that Bret Harte's short story In the Tules does make an implicit pun on Ultima Thule. However, the hits for {"in the toolies"} are a different matter:

Ok proof I've lived in the toolies just a tad too long, as I find that amusing.

There was a sense that we were out in the provinces, in the toolies.

At the time, this stretch of the old Route 66 was still "out in the toolies."

Please picture me and two tiny little kids in a very small stone house WAYYY out in the toolies.

You may find that it sometimes have you stopping so far out in the toolies that no hotels/campgrounds are anywhere nearby.

And so on. This seems to be a case of a word in fairly common use that is spelled one way when it's meant literally, and a different way in a figurative meaning. I wonder if it was Millar's choice to spell it "tules" in Black Money, or the idea of a copy editor at Knopf?

[Update: several readers have pointed me to a lovely page about the natural history of tule marshes of California's central valley, which also cites "out in the tules" as an equivalent to "out in the sticks". This page also mentions the "tule fogs", which several correspondents including Arnold Zwicky have described to me as their strongest association with the word.]

August 26, 2005

If it kwa's like a duck...

OK, this is "Language Log", not "Complaining about Editorial Standards at the New Yorker Log", so I was going to let it pass. But several readers have written to point out something strange in the little Mountweazels item that I linked to yesterday:

Anne Soukhanov, the U.S. General Editor of Encarta Webster’s, was the first to weigh in. “Ess-kwa-val-ee-ohnce—I want to pronounce it in the French manner—is your culprit,” she said.

It's the status of the made-up word esquivalience that's at issue, and Tom Rossen's reaction was the most pungent:

Kwa she talkin' 'bout, Willis? If that's what Microsoft's finest think is the French pronunciation of "qui", I'm at a loss for mots!

"Ess-kwa-val-ee-ohnce" is indeed a strange notion of how to pronounce esquivalience "in the French manner", but I don't think that it's safe to attribute the idea to Soukhanov. The pages of the New Yorker are by no means bereft of linguistic carelessness -- we've documented hallucinations about pronunciation and a preposterous transcription error, among other things, and the Soukhanov quote's chain of transmission is unclear. Henry Alford writes that "The six words and their definitions were e-mailed to nine lexicographical authorities", which suggests that the responses might have come by email as well; but then he uses the tag "she said", not "she wrote" or "she e-mailed", so maybe he talked with Soukhanov on the phone. If her answer was spoken, then the lamely fake representation of pronunciation is entirely Alford's. And if Soukhanov answered by email, that part of the quote might have been edited, either by Alford or by someone else at the New Yorker. This is the familiar problem of attributional abduction.

But even if Soukhanov provided the pronounciation as printed -- which I doubt -- it seems to me that the magazine is at fault. Depicting a respected senior lexicographer as ignorant of French pronunciation is a distraction from the light-hearted point of the piece. The spirit of Miss Gould is fading further.

August 25, 2005

Mountweazel and esquivalience

"It's like tagging and releasing giant turtles", says Erin McKean. Read all about in Henry Alford's Talk of the Town piece on lexicographic honeypots (though they are not identified by that name, which comes from the computer security area). I note that Alford says that esquivalience "has since been spotted on Dictionary.com, which cites Webster’s New Millennium as its source", but it's not there now.

Journal-mediated scholarly debate: slow and ceremonial conversation

Whether or not you're interested in the content of the on-going debate in Cognition about approaches to language evolution, you might find it interesting to contemplate its schedule. Here's a summary of the time line:

Hauser, Chomsky and Fitch (HCF): published in Science November 22, 2002.

Pinker and Jackendoff (PJ): Received 16 January 2004; accepted 31 August 2004. Available online 19 January 2005. Published March 2005.

Fitch, Hauser and Chomsky (FHC): Received 5 November 2004; accepted 15 February 2005. Available online 19 August 2005. Not published yet.

Jackendoff and Pinker (JP): posted on J's website March 23 2005. No information yet available from Cognition.

So Pinker and Jackendoff took a year or so to decide to respond to HCF and to send in their critique PJ, which arrived at Cognition roughly 14 months after HCF was published. It took 7.5 months for it to be accepted, and then another 4.5 months for it to be put on line, and another 2 months to appear in paper form. The response FHC to PJ was sent in 2 months after PJ's acceptance, 2.5 months before it appeared on line, and 4.5 months before it appeared in print; FHC was accepted 3 months after submission, published on line after an additional 6 months, and not published yet. Meanwhile, the response JP to FHC was completed and put on line (and thus I assume was sent to Cognition) about 1 month after FHC was accepted, and five months ago; apparently Cognition has accepted it, but it has not yet appeared on the Cognition web site.

(I'm not singling Cognition out for criticism — this is a typical sort of schedule for such sequences.)

This conversational tempo is reminiscent of 18th century correspondence between Europe and North America, or Europe and India, when a message could take as much as six months to reach its destination. If we start the conversational clock at the point where PJ was accepted by Cognition, and entirely ignore the timing and distribution of actual print media, we get the following sums for the conversational sequence PJ/FHC/JP:

Thinking and writing: 3 months

Review: 10.5 months + unknown time for JP, still not known to be accepted -- say 13.5 months?

Waiting for publication on line after acceptance: 10.5 months + unknown time for JP -- say 11.5 months?

The sums are uncertain because the time periods involved are not entirely disjoint (so that only 19 months in total have elapsed since PJ was received by Cognition), but it still seems likely that the mechanics of the system have slowed this conversation down at least as much as sending the manuscripts by square-rigger across the oceans would have done. Shouldn't there be a way to carry out scientific discussion that's a bit brisker? Certainly one good candidate for elimination is the 11.5 months or so clocked in this case by waiting for accepted articles to appear on line.

Somewhat more tentatively, I'd like to raise the question of whether the review process is always worth its cost in time. As is normal and probably inevitable in the refereed literature, this particular back-and-forth includes a number of factually doubtful statements and presuppositions. I'll cite just one example: in PJ we read that

HCF do discuss the ability to learn linearly ordered recursive phrase structure. In a clever experiment, Fitch and Hauser (2004) showed that unlike humans, tamarins cannot learn the simple recursive language AnBn (all sequences consisting of n instances of the symbol A followed by n instances of the symbol B; such a language can be generated by the recursive rule S→A(S)B).

and in FHC, we read the response that

The inability of cotton-top tamarins to master a phrase-structure grammar (Fitch & Hauser, 2004) is of interest in this discussion primarily as a demonstration of an empirical technique for asking linguistically relevant questions of a nonlinguistic animal.

The reader will naturally conclude from this that Fitch and Hauser (2004) actually did establish something about the abilities of tamarins and humans to learn the language AnBn, whereas the sad fact is that this conclusion was a serious over-interpretation of a rather limited experiment, and seems to be incompatible with later research.

In addition to such (inevitable) mistakes, the programmatic nature of this exchange results in an unusually large fraction of statements of opinion, where the role and value of the review process is especially unclear. I'll also point out that the review process, though regarded as a sacred ritual by our academic culture, is a relatively recent development. I recall reading that when Albert Einstein moved to the U.S. in the 1930s, and first submitted an article to an American journal, he was shocked and offended to learn that that it was being sent out for review. This was not because he thought himself in particular above such things, but rather because he had never encountered the practice before, so that his first reaction was that he was being singled out as an untrustworthy source. (Memory says, perhaps falsely, that I read this in Abraham Pais' wonderful biography of Einstein, Subtle is the Lord, which I don't have at hand.)

I'm a conservative sort of person, though not nearly as conservative as most academics are about their culture, so I'm not about to propose that we scrap the existing journal system. As Churchill is said to have said about democracy, it's the worst possible system, except for all the others.

But all the same, among the emerging technologies of networked text archives, links, indices and so on, there are a wide range of other possible solutions to the problems of scientific and scholarly communications that refereed journals have evolved to solve. And as a result, I'll predict that within 50 years, scientists and scholars will use a very different set of methods for communicating and discussing their research results, and the existing system of scientific and scholarly journals will survive only in a vestigial form, analogous to the caps and gowns that academics once wore all the time, and now put on only for ceremonial occasions.

[Update: Jay Cummings writes

In the upcoming Physics Today (September 2005), the story of Einstein's objection to being reviewed is told. The reviewer (with some trepidation, because after all, he knew this was Einstein) suggested a correction. Einstein refused the correction, but he turned out to be wrong.

I haven't seen the article -- I'll look forward to learning the details.

JP versus FHC+CHF versus PJ versus HCF

On August 19, 2005, the journal Cognition posted on line a 19,000-word article by Tecumseh Fitch, Marc Hauser and Noam Chomsky, entitled "The evolution of the language faculty: Clarifications and implications" (free version here), referencing an additional 6,000-word appendix "The Minimalist Program". This is the third turn in a (so far) four-turn, three-year debate with Steve Pinker and Ray Jackendoff.

Chris at Mixing Memory has posted on FHC 2005, asking especially for help in decoding Chomsky's Minimalist appendix. I'll limit myself to observing that it's entirely "inside baseball": seven pages of text that mention no linguistic facts and no specific languages, nor any simulations, formulae, or empirical generalizations. Aside from a very general and abstract account of Chomsky's view of the goals of his research, the only topic is who said what when, sometimes with a very abstract explanation of why. It's an odd document -- I can't think of anything at all comparable from a major figure in a scientific or scholarly field, except perhaps some controversies over precedence (which is not an issue here). I agree with the judgment of Jacques Mehler, the editor of Cognition, who asked for it to be cut; and it seems to me that it's a distraction for outsiders (including most of the normal readership of Cognition) to try to understand it.

However, the larger discussion of language evolution has many points of general interest, which we've touched on in this blog from time to time, and will again. So as a public service, here's a quick overview, with links, of the Chomsky/Fitch/Hauser vs. Jackendoff/Pinker story so far:

Step 1 (HCF, 2002): Marc Hauser, Noam Chomsky, and Tecumseh Fitch wrote an article in Science entitled "The Faculty of Language: What Is It, Who Has It, and How Did It Evolve?" (Vol 298, Issue 5598, 1569-157 , 22 November 2002). A free version is available here.

Step 2 (PJ, 2004): Steven Pinker and Ray Jackendoff responded with an article in Cognition entitled "The faculty of language: what's special about it?" (Volume 95, Issue 2 , March 2005, Pages 201-236 -- free version here).

Step 3 (FHC, 2005) Fitch, Hauser and Chomsky have responded, with an article due out in Cognition entitled "The evolution of the language faculty: Clarifications and implications" (free version here). The abstract refers to an "online appendix" where "we detail the deep inaccuracies in their characterization of [the Minimalist Program]". The appendix does not seem to be linked anywhere in the online paper, but it is on line here, with the authors ordered as "N. Chomsky, M.D. Hauser and W.T. Fitch", entitled "Appendix. The Minimalist Program."

Step 4 (JP, 2005): Jackendoff and Pinker will respond to the response, in an article entitled "The Nature of the Language Faculty and its Implications for Evolution of Language" (listed as "in press" at Cognition, but not yet available on line -- free version of 3/25/2005 here).

If you want a quick overview of what the conversation is about, without reading all 57,440 words so far expended by all sides, here are the abstracts, again with links to the full versions:

Step 1 (2002): Marc Hauser, Noam Chomsky, and Tecumseh Fitch wrote an article in Science entitled "The Faculty of Language: What Is It, Who Has It, and How Did It Evolve?" (Vol 298, Issue 5598, 1569-157 , 22 November 2002). A free version is available here. The abstract:

We argue that an understanding of the faculty of language requires substantial interdisciplinary cooperation. We suggest how current developments in linguistics can be profitably wedded to work in evolutionary biology, anthropology, psychology, and neuroscience. We submit that a distinction should be made between the faculty of language in the broad sense (FLB) and in the narrow sense (FLN). FLB includes a sensory-motor system, a conceptual-intentional system, and the computational mechanisms for recursion, providing the capacity to generate an infinite range of expressions from a finite set of elements. We hypothesize that FLN only includes recursion and is the only uniquely human component of the faculty of language. We further argue that FLN may have evolved for reasons other than language, hence comparative studies might look for evidence of such computations outside of the domain of communication (for example, number, navigation, and social relations).

Step 2 (2004): Steven Pinker and Ray Jackendoff responded with an article in Cognition entitled "The faculty of language: what's special about it?" (Volume 95, Issue 2 , March 2005, Pages 201-236 -- free version here). The abstract:

We examine the question of which aspects of language are uniquely human and uniquely linguistic in light of recent suggestions by Hauser, Chomsky, and Fitch that the only such aspect is syntactic recursion, the rest of language being either specific to humans but not to language (e.g. words and concepts) or not specific to humans (e.g. speech perception). We find the hypothesis problematic. It ignores the many aspects of grammar that are not recursive, such as phonology, morphology, case, agreement, and many properties of words. It is inconsistent with the anatomy and neural control of the human vocal tract. And it is weakened by experiments suggesting that speech perception cannot be reduced to primate audition, that word learning cannot be reduced to fact learning, and that at least one gene involved in speech and language was evolutionarily selected in the human lineage but is not specific to recursion. The recursion-only claim, we suggest, is motivated by Chomsky's recent approach to syntax, the Minimalist Program, which de-emphasizes the same aspects of language. The approach, however, is sufficiently problematic that it cannot be used to support claims about evolution. We contest related arguments that language is not an adaptation, namely that it is “perfect,” non-redundant, unusable in any partial form, and badly designed for communication. The hypothesis that language is a complex adaptation for communication which evolved piecemeal avoids all these problems.

Step 3 (2005) Fitch, Hauser and Chomsky have responded, with an article due out in Cognition entitled "The evolution of the language faculty: Clarifications and implications" (free version here). The abstract: