December 31, 2004

Implicature in the service of a moral panic

There's a lot to be unhappy about in J. L. King's recent book, On the Down Low (Broadway Books, 2004), but most of it doesn't have to do with linguistic issues. However, one of King's aims in the book, to sound the alarm about "straight" black men who have sex with men and the danger they present to black women, is furthered by the way he phrases his warnings. Implicature is working in the service of a moral panic over DL men.

[Added 1/1/05: Linguistic and sociological background (perhaps more than you wanted to hear, but people have been asking)... "MSM" stands for "men who have sex with men", which does not refer, as you might have imagined from working through simple compositional semantics, to men who at least sometimes engage in gay sex, but is a technical term in the social services and sociological literature for one specific subset of such men, namely men who consider themselves to be "straight" but seek out and engage in gay sex with some frequency while concealing their form of sexuality from most of the world. MSMs -- don't fuss at me about this pluralization -- are thus to be distinguished from what I call "frankly" gay and bisexual men, who identify as either "gay/homosexual/queer" or "bisexual", can be either closeted or open about their sexuality, and can be either sexually active or not; MSMs are by definition both closeted and sexually active. The expression "the DL" stands for "the Down Low". Men "on the DL" (or "in the DL life(style)"), also known as "DL men", are the black-on-black variant of MSMs, where "black" is a synonym for "African American". So "DL" is a specifically U.S. expression, and it's a folk term. In contrast, I've seen "MSM" used in U.S., Canadian, U.K., and Australian contexts, usually as a technical term; white MSMs mostly have no term for their sexual activity (which they tend to view as something more akin to a hobby than a sexuality), though they do recognize the ordinary English expression "men who have sex with men" as applying to them, which is why the expression is useful in attempts at outreach to MSMs, of whatever race or ethnicity.]

Life on the DL was last discussed here back in July. Since then I've read King's book, with some dismay, though possibly not as much as Keith Boykin, as expressed in his article "Not just a black thing" in The Advocate of 1/18/05, pp. 31-3 (Boykin, an openly gay and politically very active black man, has a book Beyond the Down Low soon to be published.) Boykin is particularly outraged at King's claim that men on the DL are the vector for the spread of HIV/AIDS among black women; he notes that the phenomenon of "straight" men having sex with men is as widespread among whites as blacks, yet HIV/AIDS is much more prevalent among black women than among white women. So Boykin sees King as engaged in a campaign of blaming the gays.

My dismay, on the other hand, is over King's fomenting a moral panic -- in this book, in television interviews, and in public appearances -- about the prevalence of DL life. Now, King lived on the DL himself for years, and he's writing about what he knows, which includes a very large number of men on the DL, so in his world the Down Low is all over the place. This view of the world finds expression in the way he frames his warnings to black women (the bold-facing is mine):

The first thing I want to say to women who are seeking DL signs or behavior traits is that not every black man is on the DL. Not every black man in your life is on the DL. (p. 128)

I also want to make sure that I am clear when I say not all black men are living a double life, a double lie. (p. 129)

Well, that's generous. Not all gay men are child molestors. Not all straight men are gay-bashers. And so on. But all these assertions that not all Xs are Y implicate that a large percentage of Xs are Y. King might well believe, given his life history, that a large percentage of black men are on the DL, but this claim is almost surely false. Estimates are hard to come by, but many studies put the percentage of men who are gay in a broad sense (including bisexuals and, despite their self-identifications, MSMs) at around 5%. Let's opt instead for the larger figure of 10% that is often bandied about. Surely MSMs are no more than half of this population, probably a good deal less. So a very generous estimate of the incidence of guys on the DL is 5%. Not an insignificant number, but scarcely a omnipresent threat to women.

King's recommendations to women are in line with the sense of omnipresent threat and moral panic that he projects. Although he concedes that

You cannot be with him twenty-four hours a day. You don't have access to his e-mail accounts or his phone calls, and you don't always know if he is where he tells you he is. (p. 128)

this very phrasing suggests that it might be a good thing if you (the typical black woman) could do all these things. He counsels vigilance ("A woman should... keep up with her man's comings and goings" (p. 131), "A woman should know her man's schedule" (p. 132), "Come home early from work one day; surprise him" (p. 132)) for pages, offering detailed accounts of how guys on the DL cheat and lie, how they hook up with one another, and so on, and even suggests drastic action:

I don't have a "sure list of signs" that will give women the answers they seek. Women can hire a private investigation company or get a very masculine-acting and -looking gay man and have him approach their man.

No, I'm not making this wild-eyed paranoia up. The irony here is that men in general, and MSMs especially, complain that their women are too controlling, interfering, demanding, full of "drama and hassles" (p. 142), so that they feel the need to escape the ol' ball and chain for undemanding companionship with other men (which for MSMs comes with easy uncommitted sex).

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

Waves, contagion, and the spread of linguistic changes

Reporting on site from the MLA meetings, Geoff Pullum tells us thatLabov has found a spreading sound shift in inland Northern cities (Buffalo, Cleveland, Toledo, Chicago, but not Columbus or Indianapolis) stopped dead by a line where the prevailing ideology of Northern Yankees (anti death penalty; pro gun control) ceases to be a typical feature of local political opinion — a sharp and rather unexpected intrusion of ideology on the course of linguistic change.

The image Geoff uses here is like that of a spreading wave, which is halted by natural barriers. But wave trains are not a particularly good metaphor for the spread of linguistic changes. Contagion is another attractive metaphor, but it too is unsatisfactory in most cases. When we look at the micromechanisms at work in the spread of variants, though, the "barrier" effect that Labov observes is not at all surprising (though it's nice to have it illustrated so dramatically).

Quite possibly Labov said this in his MLA talk, but let me say it here anyway.

For a wave to propagate, all it takes is for molecules to be in contact. The molecules that have energy transmitted to them don't have to be receptive to it; they just have to be there. The spread of linguistic variants doesn't have this automatic quality. Merely hearing some variant doesn't cause you to adopt it; you have to be receptive to it.

The contagion metaphor is a bit better, since it incorporates some notion of susceptibility to the disease, which translates in the linguistic case into some kind of receptivity to a new variant. And in some cases -- notably the spread of many lexical items -- this seems to be an adequate picture of the events in question.

But the spread of syntactic, morphological, and phonological variants requires more than contact and simple receptivity to new variants. You have to view yourself as like the people who use the variant, so that you'll be willing to accommodate to their speech to some extent. These variants spread locally, by interaction among companions. Insofar as you don't identify with people -- say, because you hold to very different ideologies -- even if you're in regular contact with them, you're unlikely to adopt their behaviors.

So there is a barrier, a social and psychological one.

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

booger blogger anaphora

ABC News has named bloggers as "People of the Year", for "providing unique insight into people's thoughts." The ABC article starts this way:

A blog — short for "web log" — is an online personal journal that covers topics ranging from daily life to technology to culture to the arts. Blogs have made such an impact this year that Merriam-Webster named it the word of the year.

By "it" ABC of course means "the word blog". This is a good example of a pronoun referring to an entity that is evoked but not named, a phenomenon that has recently come to be known as booger anaphora.

And by the way, Merriam-Webster's choice was not based on someone's subjective evaluation of lexical impact, but rather on a simple count of word lookups on their free internet site.

December 30, 2004

Wild Linguists

Much-maligned author Dan Brown is one of the few lay people who shows a proper appreciation for linguists, but not the only one. I just turned on the TV (purely for research purposes, of course) and came upon an episode of Friends. Ross was explaining why he wouldn't cancel his date for the evening:

She's an Assistant Professor in the Linguistics Department. They're WILD!So there.

CASS corpus

According to a recent wire story from Xinhua

Chinese linguists are going to complete China's largest database of spoken Chinese, on the basis of which they will compile the country's first modern spoken Chinese dictionary and grammar book.

Shen Jiaxuan, director of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) Institute of Linguistics, said the database include three sub bases such as a live Chinese conversation base whose data were collected in Beijing, a base consisting of six dialects of Shanghai, Xi'an, Guangzhou, Beijing, Chongqing and Xiamen, and a base of phonetic symbols of modern spoken Chinese.

The live conversation base now has 650 hours of live conversations recorded in Beijing, which were transferred to 8.9 million words in transcript.

The English-language web page for the CASS Institute of Linguistics is here.

I wasn't able to find out whether the recordings and transcripts will be published. I hope so -- the corpus-based dictionary and grammar will be even more valuable if the base materials are also available to scholars, as the British National Corpus and many other large linguistic corpora are.

The cited numbers for the Beijing conversational recordings and their transcripts (650 hours of conversations, 8.9 million "words") add up to about 228 "words" per minute. This leaves me uncertain about whether this should be taken to mean "words" in the lexicographic sense, or "characters" as they would be used in transcribing the conversations into normal Chinese orthography. The Chinese writing system doesn't separate "words" by spaces or any other marks, but the project aims at producing a dictionary, which will certainly be organized in terms of multi-character words, just as (for instance) CEDICT or the ABC Chinese Dictionary is. Thus e.g. dian4 shi4 ji1电视机, meaning"television (set)", is three syllables, three characters, but one (lexicographic) word.

228 whatevers per minute seems too fast for the units to be words, which I think should average about two syllables each in Beijing conversation, but it's kind of slow for syllables in conversational speech. It's probably syllables (=characters), though, with some pausing accounting for the slower rate.

Anyhow, it's terrific to see this development.

[via Victor Mair]

McCloskey on the rebounding of Irish

When Bill Poser recently pointed out to us an article about the revival of Irish, it occurred to me to ask a colleague about the subject. Jim McCloskey, Professor of Linguistics at the University of California, Santa Cruz, is one of the foremost experts in the world on the modern Irish language, and certainly the most prominent of those taking an interest in theoretical linguistics. His brilliantly worked-out and impeccably detailed theoretical works on Irish have been appearing since the late 1970s, along with philological notes (published not just about but in Irish) and a couple of popular works for an Irish audience. He regularly visits the Irish-speaking areas of Ireland to do fieldwork, and is just back from there. Here are his reactions, presented (in green, naturally) as a guest post. —GKP

Although I haven't seen the original article that Bill Poser reports on, I'll try to say something in response to his report of it. I've just come back from three and a half months in Ireland, much of that time spent in discussing these issues with a range of people (academics, teachers, broadcasters, writers, friends ...).

I think that talk of a ‘rebound’ for the language is misplaced, but I do not equate that position with pessimism. The situation is a complex and fluid one, but largely it seems to me that things are on the same trajectory that they have been on for several decades (with a couple of interesting changes). By which I mean that the traditional Irish-using communities (the Gaeltachtai/) continue to shrink and the language continues to retreat in those communities. Nobody that I know who is involved in those communities is optimistic about their future as Irish-speaking communities (though lots of other good things are happening to them and in them).

The observers I trust most (friends and colleagues engaged in intense fieldwork in Gaeltacht communities) maintain that the process of normal acquisition (for Irish) ceased in most areas in the middle 70's, and it is now increasingly difficult to find people younger than about 30 who control traditional Gaeltacht Irish. If you walk along a road in a Gaeltacht area and try to listen for the language being used by groups of teenagers and children by themselves, it is always (in my recent experience) English. Someone I know who is the principal of a primary school in the Donegal Gaeltacht reported that of the 22 children who entered his school at the beginning of the current year, only two had, in his judgment, sufficient Irish.

So traditional Gaeltacht Irish will almost certainly cease to exist in the next 30 years or so.

But what is unique in the Irish situation, I think, has been the creation of a second language community now many times larger than the traditional Gaeltacht communities (I think that 100,000 is a reasonable estimate for the size of this community). And being a part of that community is a lively and engaging business. A friend of mine who produces a weekly current affairs program in Irish on TV reports that it is always possible to do a report on whatever topic they like in any part of the country and find people who are willing and able to do the business in Irish. And it is true that certain recent developments have boosted this community and its self-confidence---the success of some poets (Celia de Fre/ine) and musicians (Liam O/ Maonlai/, John Spillane, Larry Mullen), the availability of an Irish TV channel, a vigorous presence on the net, and the opening of two trendy coffee-shops in the center of Dublin.

There is a great range of varieties called `Irish' in use in this community. People like me speak a close approximation of traditional Gaeltacht Irish and there are people who speak new urban calques, heavily influenced by English in every way. For the communities of children growing up around Irish-medium schools in urban centres it may be right to speak of pidginization and creolization (along with a lot of clever inter-language play like the recent ‘cad-ever’). Many teenagers are thoroughly bidialectal, switching easily from the version of Gaeltacht Irish they have from their parents to the new urban varieties in use among their peers.

It will be interesting to see what happens to these varieties when the model of Gaeltacht Irish becomes a memory, but one thing that is clear is that this community is not going to fade away just because the Gaeltacht fades away.And maybe that is what a half-successful language maintenance effort is going to look like (maybe that is the best that can be hoped for). It seems to be very difficult to work against the historical processes that lead to language-shift. But what the Irish experience teaches us is that it is far from impossible to create a new community of second-language users with all the usual and lively trappings (literature, music, radio, TV, journalism, schools, politics).

Of course, what is ‘maintained’ or ‘revived’ in this process, is very different indeed from the language which was the original focus of revivalist efforts. But in this context, as in most, purism is surely misplaced.

And a right guid willie waught to you, too, pal

We like the incantations we recite on ritual occasions to be linguistically opaque, from the unparsable "Star-Spangled Banner" (not many people can tell you what the object of watch is in the first verse) to the Pledge of Allegiance, with its orotund diction and its vague (and historically misanalyzed) "under God." But for sheer unfathomability, "Auld Lang Syne" is in a class by itself. Not that anybody can sing any of it beyond the first verse and the chorus, before the lyrics descend inscrutably into gowans, pint-stowps, willie-waughts and other items that would already have sounded pretty retro to Burns's contemporaries. But it's my guess that most people take the first two clauses of the song as the protases of a conditional, rather than as rhetorical questions. True, most versions of the lyrics end the lines with question marks (this is the most familiar version, a little different from Burns's):

Should auld acquaintance be forgot

And never brought to mind?

Should auld acquaintance be forgot

And days o' auld lang syne?

But a fair number of people leave out the question marks (for example here, here, and here), which suggests that the interrogative force isn't obvious. It may make no sense that way -- "if old friends should be forgotten, we'll drink to bygone days anyway." But incomprehensibility only adds to the sense of immemorial tradition, even this happens to be a borrowed one, grafted onto American culture in 1929 by a Canadian of Italian ancestry.

As Eric Hobsbawm has observed, after all, the point of invented traditions like the kilt or the Pledge is to provide "emotionally charged signs of club membership rather than the statutes and objects of the club." And what could be more evocative than a New Year's song that's sodden with quaintly impenetrable phraseology? "Is not the Scotch phrase Auld Lang syne exceedingly expressive?" Burns wrote to a friend in 1793. Well, it works for me, anyway.

December 29, 2004

Fast times in the primate brain: no special providence

An article published in Cell today compared the apparent rate of genetic evolution in four cases: nervous-system genes vs. "housekeeping" genes in primates vs. rodents (here, if you've got a subscription). The abstract:

An article published in Cell today compared the apparent rate of genetic evolution in four cases: nervous-system genes vs. "housekeeping" genes in primates vs. rodents (here, if you've got a subscription). The abstract:

Human evolution is characterized by a dramatic increase in brain size and complexity. To probe its genetic basis, we examined the evolution of genes involved in diverse aspects of nervous system biology. We found that these genes display significantly higher rates of protein evolution in primates than in rodents. Importantly, this trend is most pronounced for the subset of genes implicated in nervous system development. Moreover, within primates, the acceleration of protein evolution is most prominent in the lineage leading from ancestral primates to humans. Thus, the remarkable phenotypic evolution of the human nervous system has a salient molecular correlate, i.e., accelerated evolution of the underlying genes, particularly those linked to nervous system development. In addition to uncovering broad evolutionary trends, our study also identified many candidate genes—most of which are implicated in regulating brain size and behavior—that might have played important roles in the evolution of the human brain.

Steve Dorus, Eric J. Vallender, Patrick D. Evans, Jeffrey R. Anderson, Sandra L. Gilbert, Michael Mahowald, Gerald J. Wyckoff, Christine M. Malcom, and Bruce T. Lahn. "Accelerated Evolution of Nervous System Genes in the Origin of Homo sapiens". Cell, Vol 119, 1027-1040, 29 December 2004

The lede of the 12/29/2004 Guardian report by Alok Jha has a more breathless, not to say awestruck, take on these results:

The sophistication of the human brain is not simply the result of steady evolution, according to new research. Instead, humans are truly privileged animals with brains that have developed in a type of extraordinarily fast evolution that is unique to the species.

An article by Ronald Kotulak in the Chicago Tribune takes a similar tack, saying that "brain-building genes mutated at a tremendously rapid rate in humans, compared with the brains of chimpanzees, macaque monkeys, rats and mice".

But there's nothing in the Cell article to support the view that humans are "truly privileged" as a result of "extraordinary fast evolution", or that the rate of genetic evolution responsible for the human brain has been "tremendously rapid". The article provides strong evidence that brain size and complexity has been subject to greater selective pressure among primates than among rodents, and that this is especially true of the human lineage among the primates. But the calculated rates of brain evolution at the molecular level are small relative to (say) snake venom or virus coat proteins.

At first I thought that the Guardian's science writer had interpreted the research overenthusiastically, as journalists sometimes do, but both the Guardian and Tribune articles includes quotes suggesting that (some of) the researchers -- at least Bruce Lahn -- are complicit in this (what I take to be) misrepresentation, and perhaps even primarily responsible for it. From the Tribune article:

The findings, Lahn said, disprove the contention of other scientists who say the evolutionary process leading to the bigger human brain was simple adaptation to change--like growing bigger antlers, longer tusks or gaily colored feathers.

"We've proven that there is a big distinction," he said. "To accomplish so much in so little evolutionary time--a few tens of millions of years--requires a selective process that is categorically different from the typical processes of acquiring new biological traits."

And from the Guardian, again quoting Lahn:

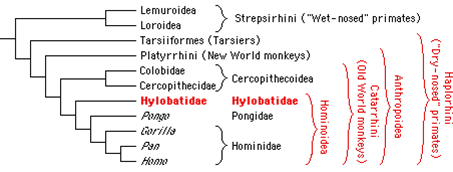

Researchers have recognized for a long time that evolution has focused on brain size and complexity in the primate and especially hominid lineages, based on measurements of brain size relative to body size -- the numbers on the right in the picture above (from the Dorus et al. article) are (ratios of) encephalization quotients (here based on the equation EQ = BrainWeight/BodyWeight0.28), indicating that macaques have about 6 times as much brain relative to their body size as rats and mice do, while humans have about 9 times as much. (You'd get somewhat different numbers by using a different exponent in the EQ equation, but under any reasonable interpretation, primates are more encephalized than rodents, apes are more encephalized than other primates, and humans are more encephalized than other apes). What the Cell article adds to this quantitative evidence from gross anatomy is quantitative evidence based on molecular changes in DNA sequences, showing that nervous-system-related genes have evolved faster in primates than in rodents. There's no attempt to show that the rate of primate brain evolution is "extraordinarily fast", just that it's faster than brain evolution among rats and mice."The making of the large human brain is not just the neurological equivalent of making a large antler. Rather, it required a level of selection that's unprecedented."

The researchers looked at 214 genes "demonstrated to play important roles in the nervous system", "expressed exclusively or predominantly in the brain", or "implicated in various diseases of the nervous system, such as brain malformations, mental retardation, and neurodegeneration". They compared these nervous-system-related genes with a set of 95 "housekeeping" genes, which are "involved in the most basic cellular functions such as metabolism and protein synthesis" and "exhibit ubiquitous expression" (i.e. in all tissues and situations). The rate of protein evolution was estimated in terms of the ratio between nonsynonymous ( Ka) and synonymous (Ks) substitution rates in the DNA sequence. ("Synonymous" substitutions don't chance the amino acid that's coded for, while "nonsynonymous" substitions do.) In the primate line, humans and macaques were compared; in the rodent line, mice and rats were compared. As graph A below shows, the Ka/Ks ratio was about 37% higher for the nervous-system genes in primates vs. in rodents, while the ratio for housekeeping genes was about the same for both genera. Graph B shows that about 55% of the nervous-system-related genes had higher Ka/Ks ratios in primates, as opposed to about 36% with higher ratios in rodents, while the balance was nearly even for housekeeping genes.

As the Cell article explains, these results could have two explanations:

One is stronger positive selection on nervous system genes in primates than rodents. The other is weaker functional constraint on these genes in primates. We argue that the possibility of weaker constraint seems unlikely, on the basis that the primate nervous system is far more complex (and therefore likely demanding greater precision in gene function) relative to the rodent nervous system.

In order to add to the plausibility of their favored explanation, the authors further subdivide the nervous-system-related genes into three groups:

The developmentally biased subgroup contained 53 genes that included patterning signals of the developing nervous system, downstream components of such signals, transcription factors that specify neuronal phenotypes, and regulators of neural precursor proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation, migration, and morphogenesis. The physiologically biased subgroup had 95 genes, comprised predominantly of neurotransmitters, their synthesis enzymes and receptors, neurohormones, voltage-gated ion channels, synaptic vesicle components, factors involved in synaptic vesicle release, metabolic enzymes specific to neurons or glia, and structural components of the nervous system. The unclassified subgroup contained the remaining 66 genes.

The "developmentally biased" subgroup shows the greatest effect, suggesting that the key thing is brain size, structure and organization, not nervous-system physiology.

There's more interesting stuff in the article, including evidence from comparisons including chimps and squirrel monkeys that the rate of nervous-system evolution at the molecular level has been greater in the hominin lineage than in the rest of primate evolution, and a (tentative) argument that human brain evolution has involved "a very large number of mutations in many genes" rather than "a small number of key mutations in a few genes".

But there's no support in the Cell article for humans being the "privileged" beneficiaries of "a type of extraordinarily fast evolution that is unique to the species", as Alok Jha tries to tell us in the Guardian. On the contrary, the authors write

Might genes involved in tissues other than the nervous system also display accelerated evolution in primates? We argue that this is a distinct possibility given the precedent found in nervous system genes. In particular, accelerated evolution of genes might be found in tissue systems that are especially relevant to the adaptation of primates, such as the immune system, the digestive system, the reproductive system, the integumentary system, and the skeletal system.

They don't ask whether genes under selective pressure in other species might show equally fast or faster changes -- but that's because they already know that the answer is "yes". In fact, the original perspective on this is that Ka/Ks ratios need to be greater than 1 to demonstrate that adaptive evolution is occurring at all, and you can see from the graphs above that the average ratio for nervous-system-related genes in the Cell paper was about 0.12. For lists of higher ratios, you can consult The Adaptive Evolution Database (TAED) here. TAED "is designed to provide, in raw form, evolutionary episodes in specific chordate and embryophyte (flowering plants, conifers, ferns, mosses and liverworts) protein families that might be candidates for adaptive evolution" and "contains a collection of protein families where at least one branch in the reconstructed molecular record has a KA/KS value greater than unity, or greater than 0.6."

For example, the sample page linked in the TAED database documentation includes the gene for the (snake venom) protein phospholipidase A2 in the Malayan Krait, Bungarus Candidus, with Ka/Ks of 2.27. Browsing for a minute or two, I found a cell adhesion protein in the zebrafish with Ka/Ks of 4.55. And on the lower links of the Great Chain of Being, the Ka/Ks ratio for sequenced genes of SARS virus during the epidemic in 2002-2003 was as high as 1.98.

Some individual genes among the "nervous-system related" set studied in the Cell paper had Ka/Ks as high as 0.833 in the primate comparison (that was MCPH1, "implicated in the control of brain size"), and the average of 0.12 was significantly higher than the rodent average of 0.09 for the same genes, but this is not some unprecedented, biologically unique level of extraordinarily fast evolution.

Given all of this, it's hard to understand why one of the paper's authors, Bruce Lahn, told the Chicago Tribune that "mutations in genes that build the brain exploded in the human line when humans split from monkeys 20 to 25 million years ago" (emphasis added). What's going on here?

There's a clue in another quote from the Tribune article, this one from Art Caplan at Penn's Bioethics Center:"There is this desire for humans to have a privileged position in terms of other animals," he said. "We try to find in intelligence or language or something that seems to distinguish us, because we want to be more like the angels than like the animals.

"But, unfortunately, the animals keep talking and being social and using tools," Caplan said. "Every time we come up with something, they do it too."

The difference is that while some animals may have one or two of these attributes in rudimentary form, humans have all of them in abundance, he said.

"The new findings look like the human brain and its hyper-evolutionary development might give us that special status relative to all the other living things around us," Caplan said.

But there's no "hyper-evolutionary development" here, unless I'm missing something. We're just seeing the molecular correlates of the long-recognized increased encephalization of the human lineage, with rates of change that are not spectacular at all relative to thousands of other well-documented cases elsewhere in nature. The resulting degree of encephalization is unique, and clearly causes (and is probably also caused by) some qualitative differences in language, tools and social organization. But what's special about us is what we see and do every day, not the Ka/Ks ratios of the brain-related genes in our lineage.

[Update 12/30/2004: As expected, this story has spread widely in the press. The Independent writes about "evolutionary overdrive"; SciTech today features "unprecedented natural selection pressure" and an "explosion of genetic mutations in the brain"; and so on through more than 50 other stories so far indexed by Google News. ]

Don't worry

The tsunami and its ever spiraling death toll may have been getting you down. But don't worry. CNN.com has had the following comforting headline up all day:

Swimsuit model survives tsunami

It links to sports illustrated which pictures the survivor herself. Hard to tell from the picture that she broke her pelvis, although she's obligingly undone the string which otherwise might have slightly obscured that part of her anatomy. [Yes. I know the picture is not actually meant to display her in post-tsunamic state. Perhaps I should have used a smiley here.]

Is it just me, or is this headline, with or without the implicature that swimsuit modeling helped her survive, bizarre?

December 28, 2004

Unredacted discussion

A little while back I sent the American Dialect Society list a link to Mark Liberman's posting on redact(ed), and we were off and running. Here I reproduce most of this discussion, unredacted ('not redacted'; see below for un-redacted 'with redaction undone'). As far as I now know, the verb redact (along with the derived noun redaction) began as a learnèd synonym for edit; developed a specialized sense in legal contexts; extended its usage in legal contexts; and then spread into more general usage as a (euphemistic) synonym for censor 'remove, black out', while preserving specialized uses in some contexts.

Mark's examples are of REDACTED being used as a reference to blacked-out bits of text that are "classified" or "sensitive" -- effectively, as a replacement for the unpleasant participle CENSORED. But the ADS-L discussion begins with John Baker's observation that in his world the verb redact is more specific than edit, scarcely overlaps with censor, and is genuinely useful:

(12/22/04) I think it's just a case of an obscure word being tapped to fill a need. I have to redact documents on a regular basis (i.e., edit them to remove identifying, privileged, or irrelevant information). If that were to be described as just editing them, it would not be clear without additional explanation, and I cannot offhand think of any other words that would make sense.

Redaction, in this sense, is what we do when we remove or disguise identifying information in corpora. Redaction, in this sense, is the imperative of our Institutional Review Boards and Human Subjects Committees.

I was up to bat next. I didn't quite get Baker's point (I preserve the typographical conventions of the original):

(12/22/04) i think the question here is: when and in what circumstances did "redact" develop from its general 'edit' sense (reported by NSOED from the mid-19th century) -- essentially, a fancy or technical *synonym* of "edit" -- to this more specific sense? the development is natural enough, but it wasn't inevitable (though, like all linguistic changes, from the point of view of the users of the innovative form it might seem so).

in any case, the long-established verb for this sort of activity was "censor" (and "black out" could easily have been specialized for this purpose; it describes well the particular method used for censoring, and is appropriately restricted to written or printed material [1]). at some point someone decided that "censor" needed replacement (and fixed on the learned verb "redact") -- undoubtedly because censorship is so, well, *nasty*. the development looks to me like linguistic laundering of vocabulary.

the development is recent enough that it's not in AHD4, which has only the older, more general, sense. i'm away from my dictionary trove at the moment, so i can't speak about other dictionaries. a lot of the google hits are for the older sense, but then there's:Pixel-counting can un-redact government docs: A Luxembourgian/Irish security research team have presented a paper on a technique for identifying words that have been blacked out of documents, as when government docs are published with big strikethroughs over the bits that are sensitive to national security. (http://www.boingboing.net/2004/05/10/pixelcounting_can_un.html)Delta Dental Plan will redact all but the last four digits of the SSNs on electronically submitted documents and on ID cards. ... (www.deltamass.com/benefitsadmins/ pdfs/Fall%202003%20Check%20Up.pdf)"redaction" has a parallel sense in some contexts, not surprisingly.

[1] is "redact" ever used to describe the censoring of audio material, that is to describe bleeping (out)?

Then Ben Zimmer chimed in with an actual early citation:

(12/22/04) The earliest relevant cite on the Nexis database suggests that US government officials began using "redacted" as a synonym for "censored" in the '70s:(Washington Post, Dec 19, 1978, A2) Prosecutors in the FBI break-ins case mistakenly circulated to defense lawyers highly classified material that is only supposed to be seen or discussed in a spy-proof vault.Attorneys for three former top FBI officials charged in the case made the disclosure yesterday in a lively pretrial hearing where they protested Justice Department attempts to get the documents back for censoring as part of a proposal to place strict limits on collecting new information.[...] The lawyers voiced special opposition yesterday to a government request that they return their clients' grand jury testimony to be "redacted" - censored - of material containing "sensitive compartmented information (SCI)."A bit more from this case, from an AP wire story that appeared in the New York Times:(New York Times, Dec 19, 1978, p. A12) Alan I. Baron, who represents the former acting FBI director, L. Patrick Gray 3d, said, "We are being denied the right to conduct a defense. The Government wants an unlimited right to redact information as to intelligence techniques, and that's what this case is all about."The term "redact" has been adopted by the Government and in this context means censorship of classified material. Barnett D. Skolnik, a Justice Department lawyer, said, "We are redacting in good faith."Seems clear that the lawyers representing the Government needed a euphemism for "censor" in this case -- it would be difficult for them to say, "We are *censoring* in good faith."

Next, John Baker went back into the legal literature and took things into the '50s:

(12/22/04) It may be that the term began as a legal term, which in large part it continues to be. It certainly predates the '70s. Here's an early use from 1957:<Justice Bastow and I agree that feasible means should have been adopted to redact DeGennaro's confession and admissions,--before their introduction into evidence,--so as to restrict their contents to his own inculpations, and thus have avoided any possible prejudice to Lombard.> (People v. Lombard, 4 A.D.2d 666, 669 n.2, 168 N.Y.S.2d 419, 423 n.2 (N.Y. App. Div. Dec 10, 1957).)Here's what the leading legal dictionary, Black's Law Dictionary (8th ed. 2004), has to say:<redaction (ri-dak-sh<schwa>n), n. 1. The careful editing of a document, esp. to remove confidential references or offensive material. [Cases: Criminal Law 663; Federal Civil Procedure 2011; Trial 39. C.J.S. Criminal Law §§ 1210-1211; Trial §§ 148-153.] 2. A revised or edited document. -- redactional, adj. -- redact, vb.>I don't think this is the same as censoring, although in some cases both terms might apply. Here's what Black's says about censor:<censor (sen-s<schwa>r), vb. To officially inspect (esp. a book or film) and delete material considered offensive.>

At this point, I tried to tie the whole thing together:

(12/22/04) this definition of "censor" takes us pretty far afield. the relevant sort of censoring in our context is removal of material because of its possible information value to outsiders (not because it is confidential to the source or because it is offensive). think censoring of wartime letters.

it looks like "redact(ion)" started as a legal term with a specialized meaning (in particular, editing to remove references confidential to sources) and then extended its usage, still in legal contexts, to such editing done for other purposes; the word then encroaches considerably on "censor(ship)" in its restricting-information sense.

And then today Bethany Dumas returned us to Mark's original data:

(12/28/04) I recently received a lengthy legal document from a lawyer. A great deal of information had been removed from the document. The removal was accomplished in each instance by omitting a section of the document. For each instance of removal, this item appeared:[redacted]

[Late-breaking ADS-L addition, 12/29/04: Doug Wilson observes that redact has shifted in the kind of direct objects it takes:]

It seems to me that the most pronounced novelty in recent use of "redact" is being ignored to some degree.

"Redact" historically means virtually exactly "edit" AFAIK. So if an editor alters a paper by deleting the entirety of its fourteenth paragraph it is conventional to say that the paper was edited, or that the paper was redacted. But I don't think it's conventional in such a case (until recently) to say that the fourteenth paragraph was redacted [or edited]; the fourteenth paragraph would conventionally be said to be deleted, removed, expunged, etc., even edited *out* ... but not just edited or redacted or altered (it's gone!).

Nowadays one sees "redact" applied specifically to the deleted material itself, so that "redact" not only has become specialized to "edit by deletions" (and after all most editing is more by deletions than otherwise) but has drifted away to the extent that it has come to mean "delete entirely", which is generally not within the range of unadorned "edit" or of traditional "redact": "I edited/redacted your paper" would not traditionally be used for "I deleted your whole paper", and "I edited the fourteenth paragraph" would not be the way to express "I removed the fourteenth paragraph entirely".

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

It's your choice at the MLA

John Strausbaugh's story about the Modern Language Association meeting currently taking place in Philadelphia (here if you register with The New York Times) is aptly described by Arnold Zwicky as pissy and snarky. Strasbaugh would have you believe that the meeting is all loopy feminists and rampant queers clamoring to be more outrageous than each other. It isn't. I'm at the MLA too, reporting for Language Log (a news source you can trust, one that has not had to dismiss a reporter and two editors for running dozens of faked stories).

Let me tell you a bit about the meeting. There are a staggering 774 separate events on the program. Yes, there is feminist research, and studies of gay literature, some serious, some less so. There are dull titles and provocative ones (abstracts are not published, so people try to create long and eye-catching titles; if you were trying to get your session noticed among 773 others, you would do the same). The question is whether you go looking for gaudy titles to make moronic jokes about or whether you have an interest in language and literature. If the latter, you can choose from a vast range of serious stuff.

I chose a presentation by sociolinguist William Labov this morning. Strikingly original, gripping in its import, compelling in its presentation. Labov has found a spreading sound shift in inland Northern cities (Buffalo, Cleveland, Toledo, Chicago, but not Columbus or Indianapolis) stopped dead by a line where the prevailing ideology of Northern Yankees (anti death penalty; pro gun control) ceases to be a typical feature of local political opinion — a sharp and rather unexpected intrusion of ideology on the course of linguistic change. Labov is a giant of the field with a constantly progressing research program (he is reportedly 75, but looks about 50 and works like a man of 30, so this age statistic is not very useful). The session was worth the price of registration all on its own, in the opinion of this reporter. And I could be wrong, but I don't think I saw Strausbaugh in the session. He may have been off somewhere being pissy and snarky and trivial.

Here comes the accusative

Seth Kanter, author of Ordinary Wolves, on NPR's Morning Edition, 12/28/04:

People are used to these stories of Alaska that are romantic and beautiful, and flowing wilderness, and here comes me with, y'know, an assault rifle and a jug of R&R.

Note the bold accusative. And note that a nominative, as in here come I, just won't cut it.

The English construction with fronted motional adverbial -- Along came Jones, There goes the neighborhood, Into the valley of death rode the four hundred -- has been studied for a long time. One of its little peculiarities is that along with front placement of the adverbial goes inversion of main verb and subject. Uninverted examples are possible but usually marked: Jones came along 'Jones arrived', There the neighborhood goes, Into the valley of death the four hundred rode. The preference for inversion is at least in part metrical: inversion yields an alternating accent pattern on constituents, with the main accent on the final constituent, which is focused.

When the subject is a personal pronoun, however, the uninverted pattern is hugely preferred: Along he came, There it goes, Into the valley of death they rode. Again, the preference is at least in part metrical: personal pronouns are normally unaccented, so that the uninverted pattern has an alternating accent pattern on its constituents. With unaccented personal pronouns, the inverted pattern is unacceptable: *Along came hĕ, *There goes ĭt, *Into the valley of death rode thĕy.

Now, you'd think that this could be easily fixed, just by putting an accent on the inverted personal pronoun. Accented it is generally iffy, so I'll put it aside, but even the other pronouns don't sound great: ??Along came hé, ??Into the valley of death rode théy. What to do, what to do? Especially if you want the pronoun in final, focus position.

Well, this is where we came in, with the use of an accusative pronoun in the inverted construction: Here comes mé. Similarly, Along came hím, Into the valley of death rode thém. The third-person examples are much improved if the pronouns are clearly deictic rather than anaphoric; the first-person examples are already deictic, of course.

An incidental point: once we have accusative subjects, the third-person singular verb form comes in here comes me is just what we'd expect. English verbs in finite clauses agree with nominative subjects, but default to third-person singular otherwise; this sort of defaulting is very well known in other languages, and can be seen elsewhere in English (either it's Poor me is going to suffer for this or you can't say it at all; but certainly *Poor me am going to suffer for this is just out, as, for that matter, is *Poor I am going to suffer for this).

Ok, but what licenses accusative subjects? Putting aside some well-known complexities like coordinate subjects and also putting aside a slew of normative prescriptions, the basic rule for nominative/accusative choice in English is: nominative for subjects of finite clauses, accusative otherwise. This rule has to be understood literally: only subjects of finite clauses; things understood, or interpreted, as subjects of such clauses don't count. So free-standing pronouns are accusative, even when they're interpreted as subjects: Who did that? Me. On the other hand, the subjects of "present subjunctive" clauses, which are finite but nevertheless have base-form, rather than finite, verbs, are still nominative: I demand that she be chair

This rule would, however, predict nominative case in the inverted motion examples, and agreeing (rather than default) verb forms would go along with that: *Here come I. Oops.

(Notice the contrast between this inversion construction and the celebrated Subject-Auxiliary Inversion (SAI), which always has nominative subjects (and they are accented): Kim would object, as would I, *Kim would object, as would me.)

I can see two ways of describing what's going on here. One way is just to say that the inverted motion construction (or constructions) has accusative subjects. Accusative case is a stipulation, as it apparently is in the construction that poor me is an exemplar of. Stipulations happen, after all.

Another way is to analyze the inverted motion construction as having two parts, in a kind of setup/payoff paratactic arrangement also seen in some other constructions: Here's the problem: the frammis and The issue is: the virus and even What bothers me (is): their passivity. That is, the inverted motion construction has two immediate constituents, a setup consisting of a motional adverbial followed by a motion verb, and a phrase serving as the payoff. So long as the payoff phrase is not actually a subject (even though it's interpreted as the subject), the basic case rule would predict accusative case.

Yes, it's speculative, and it needs some filling out (just what is the grammatical function of the payoff?). But it's not entirely crazy.

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

Mountain Tidal Waves

An indication of the salience of 津波 tsunami in Japanese life is the fact that one term for landslide is 山津波 yamatsunami "mountain tidal wave".

MLA Story

My favorite story about the Modern Language Association convention was in an

article in the New York Times many years ago. I no longer have

the citation, but I copied down the relevant bit:

Posted on a convention announcement board is an agitated adolescent

scrawl:

Did your parents force you to come to MLA? Are you going stir-crazy, like me? Call if you are age 18 and just want someone normal to go sightseeing with!!Red-inked below, in a firm professorial hand:

Watch punctuation. Vary sentence structure. Try not to end sentences in prepositions.

December 27, 2004

Eggheads' Naughty Word Games

So goes the New York Times headline (p. B1, 12/27/04) for this year's pissy snarky story (by John Strausbaugh) on the Modern Language Association meetings. While admitting, "The convention has become a holiday ritual for journalists", the piece goes on to revel anyway in the wackiness of those "postmodernists, multiculturalists, feminists and queer-theory advocates", piling on astounding titles, especially the sexy ones, and summarizing things as follows: "The association has come to resemble a hyperactive child who, having interrupted the grownups' conversation by dancing on the coffee table, can't be made to stop." (This is not a quotation; this is the journalist's own voice. It's not labeled as opinion, but, hey, this is a feature story, so I guess anything goes.)

Concluding sentence, of a story with 24.25 column-inches of text: "And yes, many believe that the press is encouraging them [the freak show contingent of the MLA] by continuing to pay attention."

I know, I know, the editor made him do it. (But I think that he secretly enjoyed it, and lord knows it's an easy story to write.)

By the way, other papers picked up the story; the pared-down Palo Alto Daily News version ran (on page 1) under the nutty head "Language purists, rebels face off".

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

Meaning and Necessity

Heard today on NPR, one for the "contingent fatalities" file: "Tsunami is a Japanese word for a good reason."

UIMA

James Fallows has an article in yesterday's NYT business section under the headline "At I.B.M., That Google Thing Is So Yesterday". He's talking about UIMA, which I've heard pronounced as "weema", and which stands for Unstructured Information Management.

If you're interested in more, there's a whole issue recent issue of IBM Systems Journal, 43(3), entitled Unstructured Information Management:

Unstructured information represents the vast majority of the data collected and accessible to enterprises. This data may be in various formats and may lack the organization of traditional sources such as database records. Exploiting this information requires systems for managing and extracting knowledge from large collections of unstructured data and applications for discovering patterns and relationships. This issue presents eight papers on the tools, methods, and architectures which are evolving for managing unstructured information in areas such as life science and market research.

Here's an IBM diagram that lays out what this is all supposed to do:

On 12/16/2004, IBM posted to alphaWorks its Unstructured Information Management SDK ("Software Development Kit"), from whose User's Guide the previous picture came:

Unstructured information management (UIM) applications are software systems that analyze unstructured information (text, audio, video, images, etc.) to discover, organize, and deliver relevant knowledge to the user. In analyzing unstructured information, UIM applications make use of a variety of analysis technologies, including statistical and rule-based Natural Language Processing (NLP), Information Retrieval (IR), machine learning, and ontologies. IBM's UIMA is an architectural and software framework that supports creation, discovery, composition, and deployment of a broad range of analysis capabilities and the linking of them to structured information services, such as databases or search engines. The UIMA framework provides a run-time environment in which developers can plug in and run their UIMA component implementations, along with other independently-developed components, and with which they can build and deploy UIM applications.

More specifically

UIMA is an architecture in which basic building blocks called Analysis Engines (AEs) are composed in order to analyze a document. At the heart of AEs are the analysis algorithms that do all the work to analyze documents and record analysis results (for example, detecting person names). These algorithms are packaged within components that are called Annotators. AEs are the stackable containers for annotators and other analysis engines.

Unfortunately, the downloadable stuff is just a development framework -- no interesting Analysis Engines or Annotators are supplied. IBM's framework would be more likely to be widely adopted, instead of various emerging (partial) alternatives, if at least a basic set of analysis methods (and procedures for training new ones) were provided.

Another IBM banner recently raised is Autonomic Computing, featured in another recent issue of the IBM technical journal:

The development of autonomic computing will make systems capable of self-configuring, self-healing, self-optimizing, and self-protecting, analogous to the abilities of living organisms with autonomic nervous systems. In this issue, an overview, 15 papers, and the Technical Forum present concepts, directions, and current work in the evolving research on autonomic computing for such areas as systems architecture, server infrastructure, systems management, security, service, applications, and the effect on users. This issue is an initial contribution to the creation of a body of literature on autonomic computing.

Irish on the Rebound?

Tom Hundley of the Chicago Tribune reports some good news about Irish, a language that has long been giving way to English. Although Irish is a required subject in Irish schools and since 1922 has been the national language of Ireland, outside of the small area known as the Gaeltacht, whose population is only 83,000 (1991 census), few people actually used Irish in their daily lives. Even in the Gaeltacht over two-thirds of Irish speakers use the language less than once a week according to the Central Statistics Office. However, the number of people reporting themselves as Irish speakers rose 9.8% from 1.43 million to 1.57 million between 1996 and 2002, and over the last twenty years, the number of Irish-medium schools has increased tenfold. According to Padhraic O Ciarda, an executive at Irish-language television station TG4, over the past decade it has become cool to speak Irish. Irish has gone from being the language of the poor, rural, and backward, to being a symbol of the new, modern, prosperous Ireland. Indeed, here's a website promoting cultural tourism in the Gaeltacht. In addition to the usual sorts of tourist activity, they offer Irish language instruction.

I've learned to be skeptical of reports of good news about endangered languages, but Irish may be recovering.

December 26, 2004

Ginger Snap

In my post on gingerly, I suggested that one curiosity of the adverbial use is people's reluctance to back-form an adjective ginger. Not so fast, emails Charles Belov, who reports that a Google search on ginger steps -- which of course I should have done myself before issuing my pronouncement -- turns up a number of instances of an adjectival use:

In the Night Kitchen... marks Santen's first solo foray, taking a few ginger steps away from his longtime collaborative project Birddog.Lack of walls and throngs of gawking passengers attracted a host of children, initially in curiosity and later with hesitant, ginger steps into participation.

The songwriting is studied and careful, guitars taking ginger steps through the melodies.

Since this use of ginger is considered obsolete by the OED, these instances suggest a re-invention via back-formation rather than a survival of the old word. And for these writers, gingerly is pretty clearly just a common-or-garden adverb formed in -ly. But the adjective is still relatively rare. A Nexis major papers search on "gingerly way," "gingerly fashion," or "gingerly manner" turns up 124 hits; a search on the same phrases with ginger turns up just one, from the Washington Post (2/15/1988):

In a very ginger way on Iowa caucus night, just before a commercial, Rather told viewers, "Vice President Bush declined our request to be interviewed on this broadcast."

It seems fair to conclude that for most people who use gingerly as an adverb, it has the distinction of being the only manner adverb formed in -ly (well, make that the only one I can think of) that isn't formed on an adjectival stem -- that is, unless you assume as I do that the word is really a haplologized version of gingerlily. Not a reason to condemn it out of hand, but I'm still going to give it a pass.

About half

According to an AP Newswire story on the recent midwest storm,

'They're about half-scared to drive fast today,' Kentucky state trooper Barry Meadows said.

The American Heritage Dictionary says that half as an adverb means

1. To the extent of exactly or nearly 50 percent: The tank is half empty. 2. Not completely or sufficiently; partly: only half right.

So did trooper Meadows mean that drivers were scared to the extent of 50%? or that they were not completely or sufficently scared? We'd have to ask him, but my bet is that he meant to let us know that drivers were like, really scared. In support of this view, the same AP story mentions 5-foot snowdrifts, "more than 100 stranded travelers ... rescued from their snowbound vehicles", hundreds of abandoned cars, sections of interstate being closed, and so forth.

There's another case of a modifer based on half used as an intensifier. The OED notes the use of not half to mean "extremely, violently" as well as "to a very slight extent":

3. not half: a long way from the due amount; to a very slight extent; in mod. slang and colloq. use = not at all, the reverse of, as ‘not half bad’ = not at all bad, rather good; ‘not half a bad fellow’ = a good fellow; ‘not half long enough’ = not nearly long enough; also (slang), extremely, violently, as ‘he didn't half swear’.

I guess that "didn't half" became an intensifier by (partial?) conventionalization of ironic understatement. In the case of "about half", something else seems to be added to irony and/or modesty. Maybe there's a bit of uncertainty about whether the modified phrase is exactly the right way to put it, comparable to Muffy Siegel's analysis of like as "used to express a possible unspecified minor nonequivalence of what is said and what is meant". And the basic meaning "partly" is always still lurking defensively in the shadows, ready to be called forward when socially stigmatized characteristics are being confessed or attributed to others.

In the Charlie Daniels song "Good Ole Boy", some negative self-evaluations are qualified with "little" and "about half"

I'm a little wild and a little bit breezy

Rollin 'em high and ridin' 'em easy

Hog wild and woman crazy

About half mean and about half lazy

But I know what I am

And I don't give a damn

Cause I'm a good ole boy

even thought the verses make it clear that the singer is proud of having pretty well pegged the meter on wild, breezy, mean and lazy. Well, maybe you've got to refer to another song to get the details on lazy. And there I'd say that Daniels wants us to interpret layin'-around-in-the-shade as a sort of countrified appreciation of the Second Noble Truth:

Poor girl wants to marry and the rich girl wants to flirt

Rich man goes to college and the poor man goes to work

A drunkard wants another drink of wine and the politician wants a vote

I don't want much of nothing at all but I will take another toke

In a 1977 novel by Dan Jenkins, "Semi-Tough", a couple of football players from Texas and their friends use semi as as a jokey substitute for colloquial half. The book was made into a semi-popular movie, which spread semi (used to mean "very") around for a while.

This may remind you of an old controversy over another scalar predicate: if a poor performance is half-assed, is a good performance no-assed or full-assed?

December 25, 2004

Gingerly We Roll Along

"It was a gingerly first step," The New York Times' Erik Ekholm and Eric Schmidt wrote on December 24, in a page one article about the return of some residents to Falluja (or "war-ravaged Falluja," to give the city its official name). The sentence caught my attention merely because it used gingerly in what I always assumed to be the correct way, as an adjective. That's so rare as to be newsworthy -- if you do a Nexis search of the previous 50 instances of gingerly in the Times, going back to July 1, 2004, you find it used an adverb every single time:

... a part of its anatomy that, as Mr. Benepe put it gingerly, ''separates the bull from the steer.'' (12/21/04)

...his chubby right foot pressing gingerly into her wrist... (12/20/04)

A couple of cleaning women in white uniforms stepped gingerly around the large potted palms... (12/19/04)

Everyone slurped, adding the sauces or not, gingerly tossing in more bean sprouts for crackle. (12/19/04)

...behavioral economics, which is gingerly stepping away from the economists' orthodoxy that humans are eternally rational... (12/19/04)

Maybe I should throw in the towel on this one, I thought, but then began to wonder whether there was ever actually a towel for me to be holding in the first place.

In defense of the usage, gingerly began its life as an adverb. It was formed from the adjective ginger, "dainty or delicate," and the OED gives citations of its use as an adverb right up to the end of the 19th century -- the adjectival use appeared in the 16th century. And unlike most other adjectives in -ly, like friendly or portly, gingerly has an adverbial meaning, so that it can only apply to nominals denoting actions (like "step" in Ekholm and Schmidt's article); otherwise it requires a clumsy periphrasis like "in a gingerly way." Moreover, Merriam-Webster's exhaustive Dictionary of English Usage gives no indication that anybody has ever objected to the use of the word as an adverb.

But the adjective ginger has been obsolete for a long time, and it's notable that nobody is tempted to back-form it anew, as in "his ginger handling of the question," which is what you'd expect if the adverbial gingerly were really analyzed as composed of the root ginger plus the derivational suffix -ly.

What we seem to have here, rather, is a haplology (or "haplogy," as some linguists can't resist calling it), the process which gave us Latin nutrix in place of the predicted *nutritrix and which leads people to say missippi instead of mississippi. Gingerly is just the way the mental lexicon's gingerlyly comes out on the tongue or the page. That's natural enough, but there's something to be said for insisting that the word be used as an adjective, as one of the small obeisances we make to the capriciousness of grammar. So, kudos to Ekholm and Schmidt, one each.

The law of the excluded bowling alley

Thomas Shannon said that "[y]esterday was one of the worst days of my life". That's because the Bloomberg wire service reported that Shannon's bowling alley chain was partly owned by Yasir Arafat, or at least by "Palestine Commercial Services Co., a Ramallah, West Bank-based holding company" controlled by Arafat through his financial advisor Mohamed Rachid.

The AP wire service story quotes Shannon as saying "We don't choose to be affiliated with any political-based organization, especially one that may or may not have ties to things we find absolutely abhorrent."

There's an interesting point of interpretation here. What Shannon means, I guess, is that the question of whether the PA has ties to abhorrent things is a serious one, worth thinking about; or maybe he means to assert that such ties exist, while weakening the assertion so as to avoid offense or lawsuits. Weasel words like "may or may not [have property P]" are often used to flag uncertainty while still getting the idea out there. This is a perfect way to spread a rumor: "Madonna may or may not be pregnant".

Logically, this phrase offers perfect deniability while transmitting no information whatever. That's because it's necessarily true, no matter what P is. At least, "it's possible that P or it's possible that not P" is a theorem in just about anything worth calling a modal logic (given the "law of the excluded middle", which says that "P or not P" is always true, and the fact that if P is true, then P is possible, at least for alethic modality). So strictly speaking, I myself may or may not have ties to things Mr. Shannon finds absolutely abhorrent, and so may you. Not only Madonna, but also Geoff Pullum may or may not be pregant. In order to conclude that these statements are literally true, we don't need to learn anything more about my ties, your ties, Mr. Shannon's moral sentiments, or Geoff Pullum's physiological state.

There's a principle of relevance here. If you ask me why I don't trust X, and I say "well, I'm always uneasy about someone who may or may not be an embezzler", I'm communicating a fairly specific suspicion. Literally, it's true of every single one of us that we may or may not be an embezzler -- or drug dealer or a saint -- but the fact that I choose to raise the particular issue of embezzlement by X communicates something in and of itself.

December 24, 2004

Living, staying, resting, standing, being

The stay/live thing that Geoff Pullum started has morphed into Bill Poser's allusion to "J'y suis, j'y reste" as uttered by the commander of the French forces in the Crimean War, and that's caused me to think of Martin Luther's famously recalcitrant "Hier stehe ich" at the Council of Worms.

Now I'm trying to find out just what Luther said. No question that the man was as stubbornly unmoving as a hunk of granite, but there's some question about what words he used.

Look, I had a Lutheran childhood, before I traded up to the Anglicans and then trucked on out of church affiliation entirely, and what I was taught as a kid was that Luther locked his legs, gritted his teeth, and defiantly intoned: "Hier stehe ich, ich kann nicht anders" 'Here I stand/stay, I cannot do otherwise' (or something like that in English). But when I check sources, some of them quote it this way and some of them have Luther saying "Hier stehe ich und kann nicht anders" 'Here I stand/stay and cannot do otherwise' -- a small difference, one of stylistic choice, but not literally identical to the version I was taught. Everyone seems to agree that he went on to finish with the dramatically pious "Gott helfe mir, Amen".

Lord knows what the man actually said. There were no council stenographers taking down the proceedings. What we have now is, apparently, recollections from years afterwards. You have to suspect that the text got polished up some in the intervening years.

In any case, there's that stand/stay business with the German verb stehen.

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

Talking animals: miracle or curse?

There's a widespread European superstition that at midnight on Christmas Eve, animals are able to speak in human voices. There are some heartwarming treatments of this story, in which the gift of speech is God's thanks to the animals in the manger in Bethlehem, and the animals use this gift to help humans. However, in most of the versions of the story, overhearing the animals' midnight speech is very bad luck.

In some cases, the animals predict misfortune.

"Once upon a time there was a woman who starved her cat and dog. At midnight on Christmas Eve she heard the dog say to the cat, `It is quite time we lost our mistress; she is a regular miser. To-night burglars are coming to steal her money; and if she cries out they will break her head.' `Twill be a good deed,' the cat replied. The woman in terror got up to go to a neighbor's house; as she went out the burglars opened the door, and when she shouted for help they broke her head."

Again a story is told of a farm servant in the German Alps who did not believe that the beasts could speak, and hid in a stable on Christmas Eve to learn what went on. At midnight he heard surprising things. "We shall have hard work to do this day week," said one horse. "Yes, the farmer's servant is heavy," answered the other. "And the way to the churchyard is long and steep," said the first. The servant was buried that day week.

In these stories, occult knowledge is bad, and research beyond normal bounds creates not only unwelcome knowledge of misfortune, but also misfortune itself.

A story by Saki, Bertie's Christmas Eve, takes a different route to a similar end. Listening for the miracle of animal speech brings misfortune, but this time it's because stereotypical properties are transferred across species in the opposite direction. Bertie, it seems, can be beastly.

Staying and living

Another quick follow-up on Geoff's note regarding stay vs. live: I think stay is used instead of (or at least synonymously with) live in at least some varieties of English. While riding BART from Oakland to Concord once (maybe 10 years ago), a 40-something African American man and I struck up a conversation. At one point the man asked me, "Where do you stay?" (Maybe it was "Where you stay?" -- I was too struck by the use of stay to remember that detail.) "I live in Walnut Creek," I replied, with contrastive stress on live to emphasize that I wasn't just passing through. "What about you?" The man replied, with no particular emphasis, "I stay in Oakland."

From the rest of our conversation, I gathered the man had lived in Oakland all his life.

[ Comments? ]

J'y suis, j'y reste.

Geoff's discussion of the usage of stay with an address as complement reminded me of a joke. During the Crimean War when General Patrice de MacMahon, the commander of the French forces, was asked by Lord Raglan, the commander of the British forces, whether he could hold Malakoff fortress, he gave the famous response:

J'y suis, j'y reste."Here I am; here I stay." (The story is told in more detail here.) The joke is the mistranslation:

I'm Swiss and I'm spending the night.This is probably the only funny thing about the Crimean War.

More threats to language

As I noted here recently, advice givers often view slang as a threat to their languages. And again and again they finger another class of innovations as an agent of decay and decline: borrowings, especially from languages that they view as culturally intrusive (or invasive, or imperialistic, as the case might be). Case in point: official French hostility to English borrowings since World War II.

Sometimes the two types of threatening innovations come in a single package. That most dangerous of creatures, the street-speech borrowing.

Luis Casillas has sent me a particularly nice example of panicked response to such borrowings:

Spanglish, the composite language of Spanish and English that has crossed over from the street to Hispanic talk shows and advertising campaigns, poses a grave danger to Hispanic culture and to the advancement of Hispanics in mainstream America. Those who condone and even promote it as a harmless commingling do not realize that this is hardly a relationship based on equality. Spanglish is an invasion of Spanish by English. ["Is 'Spanglish' a Language", Roberto González Echevarría; New York Times, March 28, 1997; http://members.aol.com/gleposky/spanglish.htm]

Casillas comments:

The nice thing about that quote is that the "threat" theme is developed in a more concrete manner than it often is, because the use of "invasion" casts it in nationalistic terms, which makes the cultural issue at stake quite clear. Further down:If, as with so many of the trends of American Hispanics, Spanglish were to spread to Latin America, it would constitute the ultimate imperialistic takeover, the final imposition of a way of life that is economically dominant but not culturally superior in any sense.

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

December 23, 2004

You're only staying if you're not

In conversation last night my friend Jatin described an area in Philadelphia as "near where Professor Katz stays." I pointed out that he had apparently used the wrong verb: English does not use stay that way. The apartment in which Professor Katz lives cannot be referred to as the place where he stays. (Linguists are allowed to make this kind of remark about syntax and semantics whenever they like. Don't worry, it's not rude. It's like when you're watching birds with an ornithologist.) Jatin agreed with me immediately about the semantics: he knew how live and stay are used, but had made the slip anyway (it's an extremely common lexical error among non-native speakers of English). But it then struck me as we talked about it that the situation with this verb is very strange. The root meaning of stay is something like "remain". But you can only say you are staying at an address if you are not going to remain.

If you are going to remain there for the indefinite future, so it's your actual domicile, you can say you plan to live there. To say that you're going to be there for a fixed period but it won't become your regular domicile, you would say that you'll be staying there. You're only staying if you're not staying.

(This is the Standard English usage I'm describing, of course. Both Susannah Kirby and Eric Bakovic have pointed out that there are African American Vernacular varieties of English in which stay does mean "permanently reside", and at least three people have pointed out that the same is true of Scottish English.)

Curiously, the actual case at hand turned out to be a problematic one that hadn't occurred to me. The Professor Katz involved was Elihu Katz. It turns out that he currently spends exactly six months of the year in Israel and six months in Philadelphia, so it is completely unclear which place should be regarded as his permanent domicile (doubtless, his home is where is heart is). So that would be the one case in which it would be unclear whether to say he stays there or that he lives there.

Blending in

The briefest of footnotes to Mark Liberman's observation that Geoff Nunberg's example "page-burner" is not just a common, or garden, malaprop, but an idiom blend:

Surely the current hot number in the world of blends involving noun-noun compounds is "X BE NOT rocket surgery", as in "Look, sentence diagramming isn't rocket surgery". A few thousand Google web hits. It's a bit more complicated than "page-burner", since the contributing compounds, "rocket science" and "brain surgery", are not themselves idioms (while "page-turner" and "barn-burner" are). Nevertheless, formulaic expressions figure in "rocket surgery" examples, since what's blended are the clichés "X BE NOT rocket science" and "X BE NOT brain surgery", both conveying 'X really isn't difficult'.

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

The Meaning of Kemosabe Jokes

Mark's discussion of Kemosabe jokes raises an interesting point. If one doesn't know the background and takes the jokes literally, they seem to support the notion that Kemosabe is offensive. But the very basis for the humor is the fact that one starts off with the assumption that Kemosabe is not offensive; the punchline is the (false) discovery that it is offensive after all.

What kemosabe really means

The Lone Ranger was on the radio every week when I was a kid. The cry "A cloud of dust and a hearty ‘Hi-Yo, Silver!'" rang out often on the playground. And in third grade, I remember a rash of jokes about what kemosabe really means. The gloss in the punchline was never respectful or even friendly, so I sympathize with the notion that the term can be an offensive one.

In response to a Reuters story about the same Nova Scotia court case that Bill Poser discussed earlier today, a site called "The Jokester" has recently posted several Lone Ranger jokes. They are all suitably bad, but none offers a hypothesis about the meaning of kemosabe. My favorite Lone Ranger joke, back in third grade, was this one (also lacking a gloss for kemosabe). I think that others must have agreed, because its punch line "what do you mean 'we', white man?" seems to have become a proverbial tag line.

Gary Larsen immortalized the genre of kemosabe jokes with a Far Side cartoon in which kemosabe turns out to be "an Apache expression for a horse's rear end." And a few of the other "meaning of kemosabe" jokes that I remember from third grade are still rattling around the internets, for example here.

Kemosabe

According to this CBC News article, the Supreme Court of Canada is being asked to decide on a complaint originally submitted to the Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission in 1999.