January 31, 2005

The multi-purpose linguist

Yesterday's NYT op-ed column by Maureen Dowd is far more interesting for reasons other than this one, but consider the following passage:

After the prisoner spat in her face, she left the room to ask a Muslim linguist how she could break the prisoner's reliance on God. The linguist suggested she tell the prisoner that she was menstruating, touch him, and then shut off the water in his cell so he couldn't wash.

I've gotten used to the term 'linguist' being used to mean 'interpreter', especially lately; I understand it when 'Arabic linguist' means someone who can translate to and/or from Arabic and 'Iraqi linguist' means more specifically someone who can translate to and/or from Iraqi Arabic. (Note that it's usually assumed and/or understood that English is on the other end of the translation.) Now obviously, a really good interpreter has more than just a dictionary-and-basic-grammar-level understanding of the languages to be translated; they also tend to have a good understanding of the different customs of the people who speak those languages. And so here we have a 'Muslim linguist' -- the idea being that this linguist has an understanding of Islamic customs and can thus be called upon to share this cultural knowledge just as conveniently as they can be called upon to translate (to and from Arabic, presumably, but who knows).

I kinda wish this linguist had said, "What are you asking me for? I'm just an interpreter," and kept their big mouth shut.

[ Comments? ]

The SAT fails a grammar test

Jennifer Medina had an article in yesterday's NYT about how "the new SAT, with all its imponderables, is increasing the agitation" of high school juniors across America.

What used to be a two-part, three-hour ordeal, half math, half verbal, will now require students to spend 45 more minutes completing an extra writing section. The new section will consist of three parts - one an essay, the other two multiple-choice grammar and sentence-completion questions.

Among the sources of anxiety that the article cites are the fact that "scoring an essay is subjective at best", and the students' uncertainty about how colleges will weight the old and the new SATs, which options are required by which colleges, and the relative difficulty of the tests to be given on different dates. I hate to add to the agitation of our nation's young people, but based on the controversial grammar questions of the past, and the sample questions now on the SAT web site, anyone planning to take the new SAT should also be very worried about the type of question that the College Board calls "Identifying Sentence Errors".

I tried the two sample questions in this category. In each test sentence, I could easily see one place where some people would identify an error. However, each of the possible "errors" is doubtful at best, and "No Error" is always one of the options. As a result, my decision about how to answer becomes a judgment about the linguistic ideology of the College Board, not a judgment about English grammar and style.

The instructions tell me that

This question type measures a [sic] your ability to:

- recognize faults in usage

- recognize effective sentences that follow the conventions of standard written English

and provide the more specific directions:

The following sentences test your ability to recognize grammar and usage errors. Each sentence contains either a single error or no error at all. No sentence contains more than one error. The error, if there is one, is underlined and lettered. If the sentence contains an error, select the one underlined part that must be changed to make the sentence correct. If the sentence is correct, select choice E. In choosing answers, follow the requirements of standard written English.

OK, fair enough. Now here's one of the sentences:

After (A) hours of futile debate, the committee has decided to postpone (B) further discussion of the resolution (C) until their (D) next meeting. No error (E)

The official answer is this:

The error in this sentence occurs at (D). A pronoun must agree in number (singular or plural) with the noun to which it refers. Here, the plural pronoun "their" incorrectly refers to the singular noun "committee."

This is doubly problematic. In the first place, it raises the issue of whether collective nouns like "committee" are singular or plural, from the point of view of verb agreement as well as pronoun choice. This is a matter on which British and American norms are different -- and the instructions refer us only to "the conventions of standard written English", not to "the conventions of standard written American English" (or should that be "standard American written English", or "American standard written English"?).

In the second place, if we take committee to be singular, there is still the infamous "singular they" question, about which we at Language Log alone have written more often than I care to think about (here, here, here, here, here, among others).In fact, this kind of constructio ad sensum has a distinguished enough history to have a special name in traditional grammar: synesis:

A construction in which a form, such as a pronoun, differs in number but agrees in meaning with the word governing it, as in If the group becomes too large, we can split them in two.

Often-cited examples from the King James translation of the bible include:

For the wages of sin is death. [Romans 6:23]

Then Philip went down to the city of Samaria, and preached Christ unto them. [Acts 8:5]

As for the authority of respected members of today's community of English users, the examples on committee-rich sites like the U.S. Congress and the National Academies seem to favor they and their in anaphoric reference to committee:

I thank the committee for their time and look forward to working with them in the future.

And now we are transferring the jurisdiction over securities to the Banking Committee so that they may conduct the business of the securities industry in precisely the same way they have supervised the business of the banking and the savings and loan industries.

The panel agreed with the chair's suggestion to submit the revised chapter of findings, conclusions and recommendations to the NWS Modernization Committee for their review at the February 9-11 meeting.

If the College Board is right about this, then hundreds of thousands of phrases in the Congressional Record and similar places, which seemed fine to their authors and seem fine to me and many other competent analysts as well, are in fact grammatical errors. Could we ask for a recount here?

Here's the other practice question:

The students have discovered (A) that they (B) can address issues more effectively through (C) letter-writing campaigns and not (D) through public demonstrations. No error (E)

Again, I had no trouble seeing where the problem might be. As the official answer explains:

The error in this sentence occurs at (D). When a comparison is introduced by the adverb "more," as in "more effectively," the second part of the comparison must be introduced by the conjunction "than" rather than "and not."

But the trouble is, comparatives don't always need a "second part" introduced by "than". The "second part" may be omitted entirely:

Apartment hunters have more choices these days.

Powell fears more violence as elections loom closer

or the cited change may be contrasted with an alternative in a conjoined phrase:

For example, cattle eat more grass in winter and less in spring; more forbs in spring and less in fall and winter; and more browse in fall and less in spring.

The outlook for precipitation is much less certain, but most projections point to more precipitation in winter and less in summer over the region as a whole.

The contrasting alternative is sometimes expressed with a conjoined negative, as in this phrase from a user's manual:

If your television has a number of video inputs, it is better to go direct and not add extra cabling.

This does not seem in any way ungrammatical to me, and the alternative

If your television has a number of video inputs, it is better to go direct than to add extra cabling.

does not strike me as a stylistic improvement. More exact counterparts can be found in an interview with Ken Knabb about Kenneth Rexroth:

He had this notion that the poem was going to subvert people little by little. That it was more effective to be subtle, and not just use crude propaganda.

and a report from the British House of Lords:

We consider that the safety issue would be dealt with more effectively by JAR-OPS and not by a Directive which would overlap with existing regulations.

I don't believe that these two examples are ungrammatical, nor do I think that they would be improved stylistically by replacing the conjunctive contrast with a than phrase. The SAT example

The students have discovered that they can address issues more effectively through letter-writing campaigns and not through public demonstrations.

is also clearly not ungrammatical. I guess I agree that the College Board's preferred alternative

The students have discovered that they can address issues more effectively through letter-writing campaigns than through public demonstrations.

is a bit better, but it's still a rather awkward sentence. In any case, the answer No Error (E) seems like a plausible answer to this question as well.

Let me be clear:

- I support and uphold the norms of standard written English in spelling, punctuation, word usage and grammar.

- I agree that students should learn these norms and should be tested on this knowledge.

- I believe that well-defined violations of these norms often occur.

- I recognize that writing can be culpably awkward or unclear, even when it is fully grammatical, and that students should learn to recognize and correct examples of this.

However, I also believe that linguistic norms should be defined by the actions and judgments of respected members of the community, not the invented regulations of isolated self-appointed experts. It's patently unfair to ask students to identify as errors contructions and usages that are widely used by respected writers and viewed as acceptable by expert analysts.

I therefore have two suggestions for the College Board.

First, create a usage panel like the one that Geoff Nunberg chairs for the American Heritage Dictionary. Don't put Sentence Error questions on the SAT -- or among the practice questions on your web site -- without checking them with your usage panel.

Second, eliminate the "No Error" answer from your grammar and usage questions. Rephrase your instructions as something like:

The following sentences test your ability to recognize grammar and usage errors. Each sentence contains one example of a word choice or a grammatical choice that is often regarded as an error by skilled users of standard American English. Select the one underlined part that must be changed to avoid this perception of error.

Then a student who knows, as I do, that "singular they" is deprecated by a few authorities, but is supported by most informed grammarians, and has often been used by great writers over the centuries, will not be forced to second-guess the ideology of the test designers:

"... well, there's not really any error at all in this sentence; but there is an instance of singular they; so perhaps the testers want me to flag it as an error, in which case I should answer (D); or perhaps they are trying to catch the silly people who incorrectly believe that synesis is always an error, in which case I should answer (E); hmm, how sophisticated and well informed do I think that the designers of this test are?..."

A student who can reason along those lines certainly deserves full credit for this question; but as things are set up, it's a coin toss. If No Error (E) were not an available answer, then the student could reason

"...well, there's no error in this sentence, but there is an instance of singular they, and that must what the in-duh-viduals who designed this test want me to answer, so OK, (D) it is..."

This would still be testing knowledge of linguistic ideology rather than knowledge of English grammar, but at least it doesn't require the student to calibrate the College Board's precise ideological stance in order to answer "correctly".

[Update: if you haven't had enough, there are other posts on this subject here , here and (at paralyzing length) here.]

Air quotes in New York

We're having a nasty cold snap in New York. Plus the snow is piled high and dirty, the days are short, and current events are depressing.

But there is one thing that never fails to cheer me up walking these glum streets, and that is signs written by shop owners under the impression that quotation marks convey emphasis. One of my favorites is a cleaners that advertises its "free pick up and delivery", as if there's something abstract or hypothetical about the service. Or, another shop has Why rush? Drop off your laundry on your way to work, "pick it up on your way back home" — as if that's a song title or some kind of wise old saying. Then there's one I pass every day, where a proud candy store tells us that "when it come to nuts, chocolates and candies, we are the best".

The grammar of that last one shows that most of these shops are run by immigrants, who often have limited knowledge of English, and especially the nuances of English as it is written. What's interesting, though, is how very commonly immigrants make this particular mistake. Part of the reason is that it is an understandable mistake — even a predictable one. After all, quotation sets off something someone says, and it's a short step from setting something off to emphasizing it. For someone with a distant relationship to the printed page — at least in English — it's natural to suppose that quotation marks are highlighters, since in a way, they are.

There's nothing unusual here. For example, it is exactly these kinds of small misinterpretations that changed Old English into Modern English. A thousand years ago, I will go meant that you willed to go, that is, you wanted to go, not that you were going to go. But because what you want is often what ends up happening in the future, people gradually started thinking that I will go meant that I shall go. After a while, so many people were hearing it this way that now, I will go did mean I shall go. The immigrants are making the same kind of leap of logic about written English today.

But fans of books like Lynne Truss's Eats, Shoots, and Leaves need not fear. Written language is more resistant to change than spoken language. Plus, these immigrants' children learn traditional writing skills in school. Just as they often don't have their parents' accents, they won't be sending out wedding invitations saying "Your presence is requested."

Which means that using quotation marks as what we might call The New Boldface will just hang around as an underground alternative punctuation. New generations of immigrants will pick it up from older ones.

Or at least I hope so. There's a certain elegance to the quotation marks in this new usage; they can spark up a tired old phrase like Free Pick Up and Delivery. And they're sure better than what big marketers have been doing to fine old logos lately, as another way of highlighting. In one logo after another, the letters are now slanted to the right, so that they look like they're running like the Road Runner. I suppose the idea is to make it look like Denny's is a dynamic experience, or that Sunoco will rock your world. But life goes by fast enough. I want my Burger King Whopper to sit still.

Or, if I want to go healthier, then I could try one shop whose exquisite sign used to entice us to Create "a" Salad. I must admit I never quite understood what they were getting at there, but it did brighten many of my days.

Not everything that passes

A friend in network engineering side of things at UC Santa Cruz wrote on Saturday to ask me a linguistic question:

Yesterday the Internet2.edu web site got hacked. In place of their home page was a single line:

H4ck3rsBr Group NEM TUDO QUE ANDA DEVAGA SIGNIFICA QUE TA PARADO

It's all fixed now, but I was wondering exactly what their message was. Does this mean anything to you?

Well, Language Log does not offer a universal free translation service. We have so many other duties, covering the entire field of the language sciences — monkeys, gibbons, parrots, eggcorns, snowclones... God, the work, the pressure...

But Mark and I (he happened to be visiting here at the Santa Cruz branch office) were sort of intrigued, so we did take a lingering look at this cryptic message. Clearly Romance. Not Latin, not Spanish. It didn't take long to see that it was Brazilian Portuguese, and "H4ck3rsBr Group" is a Brazilian hackers' group (Brazil's suffix is .br). We are not by any means Portuguese-competent, but we developed the hunch that the quoted sentence might mean something like, "Not everything that passes you signifies that you're stationary", i.e., just because someone goes by you, that doesn't mean you're standing still. What we can't do is provide a context or a deeper interpretation. Is this a quotation? A proverb? Does it suggest something else in the context of the Brazilian computer world? Anyone who knows can send a tip to pullum (the site is ucsc, the domain edu). Sources will of course remain protected by the journalist's code of confidentiality: if you're a Brazilian hacker, we won't tell.

[Added later (January 31 and February 1): OK, we have many responses (thanks to all): Brazilians and others alike agree that the meaning is roughly "Not everything that goes slow means that it's stopped." It's as ill-phrased in Portuguese as this translation is in English. A more fluent presentation of the meaning might be "Just because something's going slow doesn't mean it's stopped." Devaga is not spelled in a standard way: the word is devagar, but Brazilians generally don't pronounce the final r at all, and the hackers have left it off the spelling. Ta is a very informal spelling of esta. One guess at what this highly colloquial slogan is trying to say would be that the hackers group is telling us that just because they're going slow (they're not very active) that doesn't mean they've stopped altogether. My first guess was actually that they might be making an announcement about Brazil: that it may not be a major player in cyberspace yet, but not everything that goes slow is stationary. But that turns out to be nonsense. Francisco Borges has pointed out to me that Brazil is developing a worldwide reputation in cybercrime: note "Brazil Becomes a Cybercrime Lab", "Brazil Leads Hacker Pack", and older stories like this one and this one. The latter story notes that "As a result, Portuguese has now become the lingua franca of the hacking underground." That is something we should have known here at Language Log Plaza!

January 30, 2005

Bait and switch

Idiomatic expressions that originate as descriptions of very specific event types, like bucket brigade, are inclined to get extended semantically, so that they can describe situations lacking some of the historically defining details. Recently I came across a dramatic example of semantic extension, buried in the flap about SpongeBob SquarePants, which hit the papers on 1/20/05. The NYT that day (p. A12) reported the following from Paul Batura, assistant to James C. Dobson at Focus on the Family:

"We see the video [a music video in which cartoon characters, among them SpongeBob SquarePants, teach elementary school children about multiculturalism] as an insidious means by which the organization [the We Are Family Foundation] is manipulating and potentially brainwashing kids. It's a classic bait and switch."

First, a few words about bucket brigade (lifted from my 2002 NWAV talk on "Seeds of Variation and Change"), where the historical developments can be seen as incremental moves away from an original event type that is rich in detail.

The original bucket brigade involved chains of people, buckets of water, and putting out fires. Bucket brigade can still describe such events, but the expression now has extended senses denoting emergency situations of all sorts, not necessarily fires; as a result, buckets of water aren't necessarily involved, either. At this point, the semantic extensions go in at least two different directions. The extended sense reported by Webster's New International 3 refers to chains in emergency situations, with humans not necessarily involved: 'any chain (as of persons) acting to meet an emergency'. On the other hand, the Random House Dictionary of the English Language reports an extended sense referring to human action in an emergency, with chains not necessarily involved, as in its cite: "Seeing the two guests of honor bickering, the rest of the group formed a bucket brigade to calm them."

Back to SpongeBob SquarePants. Most of the flap has concerned Dobson's claim that the music video promotes homosexuality. But according to Nile Rodgers, the founder of the foundation, nothing in the video or its accompanying materials refers to sexual orientation, nor does the video mention the "tolerance pledge" (borrowed from the Southern Poverty Law Center) that appears on the foundation's web site; the pledge counsels tolerance for "sexual identity", among a variety of other things.

The Focus on the Family position seems to be that the video is "pro-homosexual" (Dobson's word) because it will lead its young viewers to the website and so to a mention of respect for "sexual identity" (not further explained), a mention that transparently (to Dobson's way of thinking) furthers the homosexual agenda; or perhaps that counseling tolerance in general terms is covert advocacy of homosexuality and therefore reprehensible; or perhaps that the very involvement of SpongeBob SquarePants, who some see as a character of suspect sexuality (I'm not making this up, you know), contaminates the whole video. But these dubious lines of reasoning aren't what I'm interested in here. My interest is in the expression bait and switch as applied the association between the video and the "homosexual agenda". This is a huge extension of the meaning of the expression.

Your classic bait and switch is, in the words of the American Heritage Dictionary 4, "a sales tactic in which a bargain-priced item is used to attract customers who are then encouraged to purchase a more expensive similar item." Batura's use preserves the component of deception, the assertion that one thing is offered (but not specifically for sale) and another provided (but in addition to, rather than instead of, the first), and the presupposition that the thing provided is in some way unsatisfactory (but morally offensive rather than expensive). You can get from AHD4 to Batura, but it's a long trip, and I haven't found any instances of the steps along the way.

My guess is that Batura settled on "bait and switch" as a vivid alternative to "deception" or "hidden agenda", without thinking through the details.

Addendum: When I first posted on this topic to the American Dialect Society mailing list, on 1/23/05, Larry Horn replied to the list, that same day:

That is curious. In recent political contexts, I've more often come across "bait and switch" in op-ed pieces from the left, or at least from those critical of the current administration and its policies. Economist Paul Krugman in particular seems very fond of this turn, as applied especially (but not only) to the handling of Social Security and tax cuts. Nexis turns up 11 hits of "bait and switch"... from Krugman op-ed columns or, in one case, a piece by him for the Magazine... [Larry supplies a few examples here.] But clearly these are all much more conventional applications of the figure than the one involving Messrs. SpongeBob and Batura.

I wonder if there are enough critics of Bush et al. who follow Krugman in this accusation to have inspired Batura to apply the same term for their own ends, whether or not the circumstances justify it.

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

If this is Tuesday it must be minimalism

Since Mark is doubtless too diffident to tout his own mots, I can't resist quoting one from the talk he gave at Stanford on Friday, under the provocative title "A series of unfortunate events: the past 150 years of linguistics." One problem with modern linguistics, he said, is that our results have excessively short half-lives. It isn't so much that the results we get turn out not to be true ten years later -- they're not even expressible.

"Nation split on Bush as uniter or divider"

That was the puckish headline over the cnn.com report of a CNN/USA Today/Gallup poll released recently, which showed that 49 percent of the respondents believe Bush is a "uniter" while another 49 percent said he was a "divider," and 2 percent had no opinion.

Well, okay, I can see Bush supporters quarreling with the "divider" part (as in, it's not his fault -- what can you with a bunch of leftist soreheads?). But the agentive -er suffix in uniter entails accomplishment , not merely effort -- otherwise I could describe the San Francisco 49ers as winners. And for whatever reason, a "uniter" Bush clearly ain't (I mean, unless people mean by that, "well, hey, he's united me").

You'd figure Bush's supporters could live with that, particularly since the point really isn't subject to partisan disagreement. Why not just bite the bullet and say, as controversial presidents always do, that chosing the right policies takes precedence over choosing the popular ones?

But that's what polarization comes down to these days. Never mind agreeing to disagree; we can't even agree thatwe disagree.

Contaminated identities

Bill Poser complains, reasonably enough, about the attention devoted to Prince Harry in a Nazi uniform, especially in a world in which so many vastly more serious things are going wrong:

The critics are assuming that wearing a Nazi uniform is a non-verbal indirect speech act that demonstrates support for the Nazis. Not one comment on this topic that I have seen mentions the basis for this belief. Surely it is false. People routinely wear costumes representing figures of whom they do not approve. When a couple come to a party as Bonnie and Clyde, does anyone think that they approve of bank robbery? When someone dresses as a pirate, is that taken to show approval of piracy? Of course not. Wearing a costume does not indicate approval.

But not all costumes -- or assumed identities -- are equal.

I grant that none of this is rational, none of this makes sense in purely logical terms. But there's a powerful (irrational) cultural basis for the horror here: certain identitites are highly contaminating culturally, to the extent that playing with them lays the performers open to attributions of actually having the portrayed identities. [Insert some appropriate reference to Erving Goffman on stigma here.] Nazis are over the line; pirates, bank robbers, even serial killers (like Jack the Ripper) are not.

Homosexuals are also over the line. Portraying, or appearing as, a lesbian or gay man puts the performer at risk of being assumed to be homosexual, while portraying, or appearing as, a vampire or impassive murderer or wife-beater or alcoholic or whatever carries no such career risk. The effect is famous. Being gay is a contaminating identity. (Some actors manage to escape it, but nobody denies its power.)

I didn't make this stuff up. I'm just reporting on it.

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

January 29, 2005

Flag waving

As usual, I agree with almost everything Arnold Zwicky says, but I think explanatory adequacy is a suggestive example of a quirky linguistics meme for precisely the reason he says it is a bad example: as he puts it, someone who uses the expression might just as well be waving flags that say "CHOMSKY" and "MIT". Precisely! Using the term, I'm suggesting, has more to do with saying who we are than saying what we mean.

I'll buy, in humble pie contradistinction to what I said previously, that explanatory adequacy is a technical term. Quite apart from Chomsky's stated views on the meaning of explanatory, we see at least an ostensive definition in the form of explicit contrasts between theories which are explanatorily adequate, and those which are "merely descriptively adequate" as I recall Chomsky put it. (And the word merely is part of this meme.)

How productive is explanatory adequacy? Is it the case that something has explanatory adequacy if and only if it is an explanation which is adequate? If a linguist uses the phrase adequate explanation, is this then a technical term? What differs, I submit, is not the semantics, but the pragmatics. A linguist who uses the phrase adequate explanation to describe a theory would presumably deny that the theory was merely descriptively adequate. So the meanings of adequate explanation and explanatory adequacy must be closely related for linguists in general. Both phrases could be used with Chomsky's original acquisition-centered perspective in mind, although my guess is that in practice both are used without this slant: certainly the practice from Chomsky on has been to use them without heavy use of actual acquisition data. The main difference between a linguist that uses explanatory adequacy and one that uses adequate explanation is typically that the first one waves flags that the second one does not — at least, not as vigorously.

Logically, there are at least two ways that a term like explanatory adequacy could come to be widespread in the field. First, some users of a term they have seen before could be repeating it rather lazily, a boilerplate they hammer into a paper to show whether they approve of a given theory. It would then be snowclonic, to abuse the technical vocabulary of this blog. Alternatively, they could be repeating it because it really captures a feeling they take to be appropriate. And the question then is, do they have this feeing because they want to assert that some x is P, where x is a theory and P is the set of things that satisfy explanatory adequacy. Or do they have the feeling because they know that decorating their thoughts with a patina of Chomskyana will help establish their credentials and their sub-cultural affiliation? And are those linguists (I could name some) who fail to so decorate their papers failing to do so because the concepts do not refer appropriately, or because at some level they want to express their disaffectedness?

[Update: In my original post, I should have taken into account that hundreds of occurrences of explanatory adequacy are bibliographic citations of Chomsky (2001) Beyond Explanatory Adequacy. This does not affect the argument in a big way, since using Google I can put an upper limit on the number of these citations at less than 15% of the total. But perhaps it is time for me to move beyond explanatory adequacy, and figure out a better way to illustrate my pop-sociolinguistic Tensor-derived point, by finding more linguistic memes that don't fit neatly into the category of technical terms. Even better would be if someone does it for me! Suggestions sent to dib AT stanford DOT edu are welcome. So far the best I came up with is the word counterexemplify, which is used almost exclusively by linguists, although with a small minority of philosophical uses, and gets over 100 Google hits in various morphological forms. By comparison, counterexample gets hundreds of thousands of hits, mostly non-linguistic. So which linguist was it that first turned counterexample into a verb (or added a prefix to exemplify)?]

Adequately explaining explanatory adequacy

David Beaver has just taken a look at semi-technical terminology that is (largely) peculiar to linguistics, focusing on the expression explanatory adequacy and maintaining:

Maybe the compound explanatory adequacy could be regarded as a technical term in linguistics. But I had not thought of it that way, and nor do I want to now. I personally had assumed that the meaning is derived compositionally from the meanings of explanatory and adequacy, and that neither of these were technical terms in linguistics.

Not the best of examples, since this expression has been associated with Noam Chomsky ever since he made it famous in the early 60s, in explicit contrast to descriptive adequacy. He has always treated it as a technical term, though it might just possibly be semantically compositional for him, given his views on what counts as an explanation (which would make explanation and explanatory technical terms). In any case, someone who uses the expression might just as well be waving flags that say "CHOMSKY" and "MIT".

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

Stark raven mad

Rachael Briggs' eggcorn has two yolks with different syllabifications.

What can I say? Shit happens. Not always intentionally, I surmise:

Believe me when I say, I am use to crazy people. In fact, I really don't mind if you are stark raven mad.

Zeus. I'm serious. If anything happened to you, the count would be stark raven mad.

I can remember having panicky attacks at the tender age of 5, and they scarred the heck out of me. My worse ones were of severe thunderstorms, especially after getting caught out at the lake during a tornado in Kansas. I still get panicky when we have severe weather no matter where I live, but now I clean the house like a stark raven mad woman. I think I do this to try and keep the panic attack under control.

[PS. "scarred the heck out of me"? If you want to find eggcorns, go look in Kansas during tornado season.]

Star Craving Mad

Rachael Briggs sent in a lovely example of that rare subspecies the resyllabification eggcorn.

Hi. I'm one of Language Log's anonymous gentle readers, and I thought you might

be interested in the following:

A friend of mine (one of those self-proclaimed grammar types) claims to have discovered this sentence, which uses the phrase "star craving mad" in place of "stark, raving mad", on some sort of online discussion forum:

"people would ask me whats her name i said Garren they would look at me like i was star craving mad like why did you name her such a boyish name"

Since I'm supposed to be writing papers at the moment, I thought I'd google the phrase "'star craving mad'" and see what came up. Unfortunately, there's a novel by that title by an author named Miller, and most of the hits were ads for or reviews of the novel. "'star craving mad' -book -books -miller" yielded 59 results. Most were either stray references to the book or deliberate puns, but a few of them looked like real eggcorns.

"'This is my social life,' said Workentine [a food bank volunteer]. 'It gives me a reason to get up in the morning. If I just sat at home looking at the four walls, I’d go star-craving mad.'"

"The snoring was enough to drive the sanest person star craving mad."

"I'll be crying and in horrible pain and she'll toss a couple tylenol at me and rush off to appease my two younger sisters. It drives me star craving mad."The strings "star craving crazy" and "star craving nuts" turned up no hits, so I guess the eggcorn hasn't yet caught on in any big way.

Keep up the blogging! Your work affords me a priceless opportunity to procrastinate enjoyably. Okay, back to writing papers.

Always happy to be of service. And thanks for the fruits of your investigation...

[Update: in addition to David Beaver's observation about the attested alternative eggcorn stark raven mad, Q Pheevr points out that there is another available variation, star craven mad, which is "unattested qua eggcorn", being only found so far as a witting (if not witty) pun.]

What is explanatory adequacy?

There's a nice post at Tenser said the Tensor on distinctive lexical features of the linguistic subculture. The point is that the common language of a scientific subculture is not just a simple sum [the standard language of scholarly writing]+[an explicitly or even ostensively defined technical vocabulary]. In addition to the clearly technical vocabulary there is likely a huge grey area of semi-technical or non-technical quirky turns of phrase which, having been infiltrated into our community by a single linguist, pass virus-like from one paper to the next.

Tensor's examples are X motivates Y (with the meaning X provides motivation to accept Y), and standardly assumed. I would guess that it is standardly assumed by linguists that standardly assumed is not at all particular to linguistics, but would come up whenever there was something that was standardly assumed. Apparently not. Tensor points out that googling "standardly assumed" produces about 800 ghits, whereas "standardly assumed" -linguist -linguistic -linguistics -syntactic -phonology -phonological -morphology -morphological -grammar -grammatical -phrasal -clausal -indicative -subjunctive -raising produces only 67.

This is really suggestive: just how large are the differences in frequency profiles of the languages (midiolects?) of different scientific subcultures, and how rapidly do those frequency profiles change? Can we observe a Kuhnian paradigm shift in action by looking at frequency data alone? And if we can observe changes in this way, then to what extent would the changes reflect new understanding, and to what extent a desire to act different?

The first thing I could think of to test Tensor's method is the Chomskyan phrase explanatory adequacy. which I compared with adequate explanation to provide a control on the method, and also on those weird and whacky Google counts we have been worrying about lately. Here are the searches and their Google frequencies:

| "explanatory

adequacy" |

6590 |

| "explanatory

adequacy" (non-linguistic) |

937 |

| "adequate

explanation" |

96,600 |

| "adequate

explanation" (non-linguistic) |

71,100 |

The phrase explanatory adequacy is usually not surrounded by quote marks. For explanatory adequacy is something that we linguists like to present as an obvious shared goal of scientific investigation, and we generally assume that any educated reader will know just what we mean. Perhaps they will. But if that reader is not a linguist, the table above shows that the chances are that the reader will never have seen the component words organized in that way, since at least 85% of uses of the phrase (more if we look at the actual search results) are in the linguistic literature.

Maybe the compound explanatory adequacy could be regarded as a technical term in linguistics. But I had not thought of it that way, and nor do I want to now. I personally had assumed that the meaning is derived compositionally from the meanings of explanatory and adequacy, and that neither of these were technical terms in linguistics. I had thought that anyone who knows what an adequate explanation is also knows what explanatory adequacy is. Yet, at the text level, adequate explanation is distributionally quite unlike explanatory adequacy, and is clearly not peculiar to linguistics. The vast majority of hits for adequate explanation appear to be outside of linguistics.

When we use explanatory adequacy, we use words that an educated person would know, and the semantics is intended to be clear. For that reason, I've said I do not want to call it a technical term. So what is it? Well, what we are really doing when we use it is conjuring up a web of associations. Blah blah blah explanatory adequacy blah blah standardly assumed blah blah, I say, and you might almost think I have an MIT PhD. It's not so much a technical term as a term of art, or artifice, designed to tell you who I am. Or wannabe. A lexical meme, yes, but one I use with an intention to say something about who I am and what enterprise I am engaged in.

What is explanatory adequacy? I regret to have to tell you that explanatory adequacy is now part of my identity.

January 28, 2005

Grammar is bad for kids

So says an article in The Telegraph of Jan 22 2005 (via Onze Taal). One might, of course, take issue with several aspects of the position reported.

- The finding, from a study by Richard Andrews of York University, is not based upon a controlled study. Rather, it is based on historical data tracking evaluations of writing across a period in which the UK law changed as regards curricular requirements. I know of no controlled study of whether teaching grammar helps writing, but email me (dib AT stanford DOT edu) if you know better. Furthermore, any such assessment must depend on an independent characterization of what constitutes good writing.

- Teachers of writing in the UK do not, to my knowledge, standardly

receive any systematic instruction in linguistics. I am confident that

in all my years of education in the UK, I never had an English teacher

who knew what linguistics was. So any grammar instruction I received

probably would have been detrimental to my writing, had I paid any

attention. More generally, one could take the same sort of study

as the Telegraph reports on, and conclude that grammar teaching is at

present not adequate to have an effect on writing. In that case, there

should be more emphasis on grammar, especially in the training of

teachers, not less.

- Understanding the nature of language, and learning how to think about language for yourself, is independently valuable: it is an important aspect of human culture in its own right, and if used properly is relevant to other areas, such as general critical thinking skills and second language learning. Teaching how language works does not need to be justified solely by its effects on writing skills.

Defecated to eggcorn fans everywhere

The numbers are too small to award this one eggcorn status. And it's also not very eggcorny since it's not clear that the mistakes are a matter of reanalysis. But what it lacks in frequency and linguistic sophistication, this double malapropism makes up for in appeal to that small but important segment of the Language Log audience that shares my puerile, not to say scatalogical, sense of humor.

Many of the Google hits are for intentional defacate/dedicate and defacate/defect replacements, but genuine unintentional productions do seem to occur:

|

Nowadays

tourists visiting Hoa Lu

could only see two temples some 500m apart from each other, standing in

the ground of the ancient palaces: One was defecated to King Dinh Tien

Hoang and the other to King Le Dai Hanh.

|

|

|

Aerobatic

ship defecated to a great

supplier of scale sailplanes Endless Mountain Models

|

|

[Frank Delaney] remembers the night his father came home "hugely amused" because a local man had asked him why he thought Burgess and Maclean had defecated to the Russians.

[Update: gee, I'm getting confused by our own terminology now. First time I posted this I wrote snowclone when I meant eggcorn. Snowcorn? Presumably, a historically incorrect reanalysis of a standard idiom-like template. Or vice versa.]

A linguistic contribution to American politics

According to an article by Daniel Terdiman in yesterday's NYT:

Joshua Tauberer isn't a stereotypical techie with a degree in computer science or engineering. Yet Mr. Tauberer, a 22-year-old doctoral student in linguistics at the University of Pennsylvania, is the brains behind GovTrack (www.govtrack.us), a site for up-to-the-minute information about Congress.

GovTrack differentiates itself from other sites devoted to Congress both by being free and by being fresh: it sends users e-mail updates anytime there's activity on legislation they want to monitor.

GovTrack lets users track activity of specific legislators. It can also send updates via RSS, or Real Simple Syndication. The site collects information from Thomas (thomas.loc.gov), the Library of Congress's legislation-tracking site, and the official sites of the House of Representatives and the Senate.

The Time article gives links for GovTrack and Thomas, but not for Joshua -- to save you a trip to Google, here he is.

[Link by email from John Lawler]

January 27, 2005

Agreement with nearest always bad?

In "Everything is correct" versus "Nothing is relevant", Geoff Pullum takes on the claim that if sentences like the following occur (and they do), then they're part of the language, and it's contradictory for those who who style themselves as descriptive linguists to say otherwise (as Geoff did in an earlier posting):

(1) Why do some teachers, parents and religious leaders feel that celebrating their religious observances in home and church are inadequate and deem it necessary to bring those practices into the public schools?

I agree with Geoff that it's very likely that (1) should be dismissed as an example of English. It's almost surely an inadvertent "agreement with the nearest" (AWN) -- instances of which are moderately common, especially in speech. But it turns out that for many speakers, there is a very small island of AWN cases that are indeed in their language and for which the "technically correct" agreement is dreadful.

Geoff's position is essentially that mistakes happen; people say and write things that they didn't intend and will disavow if they're given a chance. This is not even a slightly daring proposal. The rich literature on errors in language depends on our being able to make a distinction between inadvertent errors, on the one hand, and differences between the "correctness conditions" ("rules of grammar", in the usual terminology, though this expression can be misleading) on the language of different people -- between error and mere variation. In many cases, the distinction is easy to make, but, as Geoff points out, sometimes the linguists might get it wrong:

One could imagine that there might be people who actually have different correctness conditions, so that the quoted sentence was grammatical for them. There could be people for whom tensed verbs agree with the nearest noun phrase to the left, for example.

There are ways to investigate these things, as Geoff goes on to say. And most of the time, when you investigate AWN examples, you discover that people just lost track of where they were in the production of a sentence and used a recent NP (instead of the appropriate, but more distant, NP) to determine agreement on the verb. This happens so often that we can usually feel pretty sure that examples like the following -- which are ridiculously easy to collect -- arise in similar fashion. Modifiers following the head of a NP are the very devil.

(2) Let's see which one of the two of you are next. (dialogue on a Beverly Hills 90210 episode, heard in rerun 6/29/04)

(3) On handout: "... discuss challenges each approach still faces...". But said: "... the challenges each of them still face..." (speaker in LSA presentation, Oakland, 1/7/05)

(4) ... what the phonetic character of the rises are... (graduate student in conversation, 1/18/05)

Especially troublesome are sentences where the head refers to something other than an individual, either because it's a mass noun (industry in (5)) or because it's a universal (everything in (6) and (7)), so that plural semantics is in the air, and then a post-head modifier contains a syntactically plural NP:

(5) Mr. Geffen said that DreamWorks had been judged unfairly in an era where the entertainment industry, particularly the music, television and Internet businesses, have gone through tremendous upheavals. ("A Monster Hit but No Happily Ever Afters", by Laura M. Holson and Sharon Waxman, NYT, 5/17/04, p. C1)

(6) Everything from doorknobs to live alligators are for sale. (reporter from Congo, NPR's All Things Considered, 6/9/04)

(7) Normally in my lab, everything that I write, including academic emails, are proofread by someone before they are sent out. (e-mail to AMZ, 3/22/04, in mail checked by staff)

So all would seem (relatively) clear, until I came across item (8), which happens to have the subject , in this case a coordinate subject, after the verb:

(8) Going to his house was what I lived for. There were liquor, music, and a strong desire for my body. (J. L. King, On the Down Low (Broadway Books, 2004), p. 33)

As I pointed out on the American Dialect Society mailing list on 12/28/04, (8) has the "correct" (plural) agreement with expletive there, but it still sounds weird to me; I'd much prefer (8').

(8') Going to his house was what I lived for. There was liquor, music, and a strong desire for my body.

A few respondents stuck with the technically "correct" (8) -- and I am not denying their judgments -- but many agreed with me that (8) was awful, (8') much better (maybe even simply the "correct" version), and (8") straightforwardly acceptable:

(8") Going to his house was what I lived for. There were drinks, music, and a strong desire for my body.

This sure looks like AWN, but oriented towards a following subject rather than a preceding one. And in fact, as I pointed out on 1/10/05 on ADS-L, the estimable Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of English Usage had already figured this stuff out. In the "there is, there are" entry, we find scholarship stretching back nearly a hundred years:

...when a compound subject follows the verb and the first element is singular, we find mixed usage--the verb may either be singular or plural. Jespersen... explains the singular verb as a case of attraction of the verb to the first subject, and illustrates it... from Shakespeare... Perrin & Ebbitt 1972 also suggests that many writers feel the plural verb is awkward before a singular noun, and Bryant 1962 cites studies that show the singular verb is much more common in standard English.

What we have here is a tiny, and very specific, AWN island -- grammaticalized, to be sure -- in the midst of a general English requirement for straightforward subject-verb agreement. Hey, these things happen.

To add a little spice to the whole thing, I should point out that my guess about (8) is that King originally wrote (8') and it was "fixed" by a copy-editor. As a little bit of evidence in favor of this idea, I note that (as I pointed out on 12/31/04 on ADS-L) in the very same book King has at least one singular agreement where many of us would have the plural:

(9) The need [for a down-low connection] and strong desire to make that connection overrides all common sense. (p. 159)

This looks like the very common vernacular pattern (spread across geographical regions) for existential-there sentences to have singular verbs, no matter what. Or possibly it's AWN (with connection as the relevant determining noun). In any case, my guess is that (9) is just something that escaped the editor's red pencil. Hard to believe that someone who wrote (9) would have gone for (8) rather than (8'). Of course, anyone who wants to do fieldwork with J. L. King can go at it.

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

Publishers are good; really!

Publishers are nice, honest, friendly, capable, and valuable people, and all of us who work with them to produce published works find that our lives are enriched by their good sense, kindness, enterprise, intelligence, and love. I want that clearly understood.

Indeed, ultimately I would very much like to reach the nirvana point of actually believing it myself. I certainly try very diligently. But people keep sending me links to one specific story of vile, utter evil, which doesn't help. And then there are the many sins of those who mess with our prose after the writing stage — yes, including those copy editors who [change to whom? —Ed.] publishers employ to change things that never needed to be changed. In one recent article of mine I found that every though had been changed to although (a real baffler, that), and since was regularly to because; and then after the final proofs, right there in the printed book as I finally received it, several new garblings were introduced by the printers, a couple of sentences lost their initial capitals, and all the arrows in formulae turned into the figure 6. Yet that was a luxuriously trouble-free experience compared to what happened to a colleague at another institution after he delivered the typescript of an accepted book to his publisher.

The book was delivered in Dec 2002, both in hard copy and electronically. (We do that these days, we authors, so that The Process Of Production Will Be Trouble Free. Ha! Ha! Read on. Unless you're an author, in which case don't, it will tie your stomach in knots.) The author received acknowledgment of both the typescript and the CD ROM. The graphics for the volume had been professionally drawn at the author's expense, and were delivered separately, both on paper and in CD-ROM form, in March 2003. Again the publisher acknowledged receipt.

Then in summer 2003 the publishers reported that their printer was complaining: the CD-ROM did not have the text, and where was it, please? It eventually emerged that the publishers had deleted their only copy of the text of the book, without realizing that they had done so, and without keeping any records. Luckily the author was able to resupply.

Months passed, and then the publishers suddenly got in touch again, to ask what had happened about the plan to supply professionally-drawn graphics. They had lost that material too, CD ROM and all. This time the author did not have other copies of the material. But luckily the graphic artist was a personal friend and supplied a new copy without extra charge.

Many months passed with no apparent movement towards getting the book out. Then in the fall of 2003 the publishers once more got in touch out of the blue to announce that proofs would arrive on 20 December. This was a terrible date for the author, the beginning of a heavy period of teaching and administration after a long period of relative leisure, so he asked if they could possibly make it a month earlier. They said no, so he made strenuous efforts to make a space in late December for work on this long and complex book, over 500 large-format, small-type pages. The time was reserved, but the proofs didn't come. December came and went with nothing from the publisher at all. When the author got in touch they said they had changed their schedule and the proofs would arrive in mid January. It was actually early February when they came. And that was when the story started to get bad (yes, up to now was the good bit).

The publisher's editor had been rather snippy about the fact that it was not permissible to make changes in the text, only to correct what were clearly typos. But when the proofs arrived the author discovered to his astonishment that there had been a copy-editing process that he had not at any point been told about. And it had made fairly significant changes to some aspects of the text. In certain cases they were more than just significant. One whole chapter was about the weird and wonderful distortions of normal English orthographic and stylistic conventions devised by kids using Internet Relay Chat. With an idiocy that may seem almost incredible, the many examples of this had been carefully copy-edited to make them conform to the usual conventions of printed academic prose, ruining their whole point.

(I say this may seem incredible, but I have heard very similar stories elsewhere: for example, an anthropological monograph by a UCSC colleague that was loaded with transcripts of spoken testimony by uneducated peasants, on which full academic English correction of all the language in the transcripts had been perpetrated by a copy editor whose work had to be undone in its entirety at the proof stage.)

When the author had originally sent in the typescript, he had also sent notes on various problematic aspects, including the fact that there were many quoted extracts from computer files which needed to be in a fixed-width, typewriter-like font. He had even mentioned this in the original proposal, remembering that with an earlier book the same publishers had ignored this problem (though they did fix it when it was pointed it out). However, these proofs again ignored the fixed-width/proportional-type distinction in the typescript, and set the computer material in the ordinary book face, adding many distinctions that are meaningless in terms of ASCII characters, such as a contrast between wide and narrow angle brackets.

Then the author noticed that the graphics in the proofs were in many cases different and much inferior to the ones he had paid to have produced, and in some cases contained plain errors. When he asked what that was about, he was told that the typesetter needed the graphic files to conform to some special technical specifications that had never been mentioned earlier, and since the ones he had supplied didn't comply, the printer had simply improvised replacements...

And so it went on, and on. I cannot reveal the name of the publisher, still less the long-suffering author, unless supplied with an enjoyable dinner and a full bottle of a good zinfandel.

But just remember, if sometimes we academics seem to be a bit testy about our experiences during the copy-editing and proofing processes for our articles and books, there are reasons.

[Added early morning, January 28: Ah, but now, in the encouraging light of the very next dawn after posting this I see I have email from England, and Kate, our lovely commissioning editor at Cambridge University Press, has received the first copy of the new textbook by Huddleston and me, A Student's Introduction to English Grammar, and copies are being mailed to us today, and because the first adopter actually wants to use it in a course that has already started, copies are being efficiently air-freighted direct to him in San Diego. It's all going like a dream. And I just know that when I see my copy it will not spell my name as "Pullman" on the cover. Because publishers really are good, they really are...]

Senses of freedom

Orlando Patterson's Op-Ed in yesterday's New York Times shows the limitations of restricting articles to a bare 4000 characters (Patterson's piece was of that length exactly, to the letter, by my Unix count of the text). It's fine as a standard piece of polemic against President Bush on foreign policy, but it contains none of the kind of analysis of the word freedom that one would expect from knowing Patterson's scholarly work. On an NPR call-in program last night I heard Patterson give a hint of this. Freedom can be several things: it can be (1) that which ensures no one has power over you (simply not being a slave); it can be (2) that which enables you to take any action you damn well choose (having personal rights of action); and it can be (3) that which permits your participation in the political affairs of your society (being allowed to vote in fair elections for the government that you prefer). The three can conflict with each other: other people's freedom of type (1) to not be slaves deprives me of the type (2) freedom to keep slaves if I choose to. My type (2) rights to smoke infringe your type (1) rights to be free from secondhand smoke, and your type (3) rights to elect a government that then makes my smoking illegal deprives me of some of my type (2) rights. Your type (2) rights to own a company so huge it can buy elections and control governments may in effect deprive me of my type (3) rights. By floating between these three sense of freedom one can make some very confusing arguments. Which freedom is it that terrorists hate, for example? Since President Bush has been making such copious use of the word freedom of late, but never makes clear which sense he intends, it is generally very unclear what he is actually saying. I was hoping to find a clearer presentation of the linguistic point in the Times article, but I was disappointed. There really isn't a trace of it. On the cutting room floor, perhaps.

January 26, 2005

"Everything is correct" versus "nothing is relevant"

On January 23 a user identified as Zink made some comments on ceejbot's blog about the Language Log post Nearly all strings of words are ungrammatical. They struck me as really interesting:

There's a funny bit in there where they try to at once claim to be "descriptivist, not prescriptivist" while at the same time decrying the word "are" in

Why do some teachers, parents and religious leaders feel that celebrating their religious observances in home and church are inadequate and deem it necessary to bring those practices into the public schools?

Sorry kids, you can't be an apple and an orange, and if you're a descriptivist, and someone honestly makes a sentence, that's an honest sentence in the language that actually is.

By "they" Zink means the Language Log staff (the post was actually mine; none of my colleagues need take responsibility for the views expressed here). What's so interesting is that it is quite clear Zink cannot see any possibility of a position other than two extremes: on the left, that all honest efforts at uttering sentences are ipso facto correct; and on the right, that rules of grammar have an authority that derives from something independent of what any users of the language actually do.

But there had better be a third position, because these two extreme ones are both utterly insane.

I actually devoted my presentation at the December 2004 Modern Language Association meeting to a detailed attempt at getting the relevant distinctions straight, after thinking them through with a great deal of help from a philosopher of linguistics, Barbara Scholz. The concepts are by no means easy to get a grip on. But let's make a start.

First, I didn't "decry" the form are in the quoted example from a letter published in the Philadelphia Inquirer). (Decrying is strong disapproval, open condemnation with intent to discredit; check your Webster.) It needs no strong public condemnation; it doesn't offend me. I merely said it was wrongly inflected. And I explained in painstaking detail why it couldn't satisfy the normal principles of English. Now, what are these things I'm calling the normal principles? Where do they come from?

Barbara Scholz and I have taken to using the term correctness conditions for whatever are the actual conditions on your expressions that make them the expressions of your language — and likewise for anyone else's language. If you typically say I ain't got no hammer to explain that you don't have a hammer, then the correctness conditions for your dialect probably include a condition classifying ain't as a negative auxiliary, and a condition specifying that indefinite noun phrases in negated clauses take negative determiners, and a condition specifying that the subject precedes the predicate, and so on. The expressions of your language are the ones that comply with all the correctness conditions that are the relevant ones for you.

Which conditions are the relevant ones for you is an empirical question. Descriptive linguists try to lay out a statement of what the conditions are for particular languages. And it is very important to note that the linguist can go wrong. A linguist can make a mistake in formulating correctness conditions. How would anyone know? Through a back and forth comparison between what the condition statements entail and what patterns are regularly observed in the use of the language by qualified speakers under conditions when they can be taken to be using their language without many errors (e.g., when they are sober, not too tired, not suffering from brain damage, have had a chance to review and edit what they said or wrote, etc.).

Sometimes, though, one can formulate the relevant correctness condition exactly right, and then observe a sentence in the Philadelphia Inquirer that does not comply with it. This is because people do make mistakes in their own language, and some mistakes even get past newspaper copy editors.

But by saying that, I'm not endorsing any right of descriptive linguists to be considered correct in their statements regardless of what people say! There's no contradiction here (though Zink thinks he sees one). One could imagine that there might be people who actually have different correctness conditions, so that the quoted sentence was grammatical for them. There could be people for whom tensed verbs agree with the nearest noun phrase to the left, for example. For such people, this would be grammatical (I mark it with ‘[*]’ to remind you that it's not grammatical in Standard English):

[*]Celebrating religious observances in home and church are inadequate.

In fact they would even find this grammatical (with the meaning "Celebrating birthdays is silly"):

[*]Celebrating birthdays are silly.

If they really did (one could check by interviewing them or recording them for a while), and if the letter in the Inquirer was written by one of them, I'd change my mind. I've made an empirical claim: I think the person who wrote the letter speaks the same language that I do, and would regard all three of the examples given so far as ungrammatical. I think the person just made a slip while writing, failing to keep in mind that they were writing a sentence in which be inadequate had a clause as its subject, and inflecting be as if it had observances as its subject, through a moment of inattention.

Zink thinks that if you're a descriptive linguist and "someone honestly makes a sentence, that's an honest sentence in the language that actually is." But this is not about honesty. It's about whether an occurring utterance matches the correctness conditions (whatever they may be) for the speaker who uttered it. Either speakers or linguists can be wrong. Speakers will sometimes speak or write in a way that exhibits errors (errors that they themselves would agree, if asked later, were just slip-ups); and linguists will sometimes state correctness conditions in a way that incorporates errors in what is claimed about the language (errors that they themselves would agree, if asked later, were just mistaken hypotheses about the language). I claimed that I'm right about the correctness conditions on verb agreement in Standard English, and that the person who wrote the letter I quoted made a slip-up. That's not a contradiction — no one is attempting to be both an apple and an orange.

And none of the foregoing has anything to do with prescriptive claims about grammar, which are a whole different story. Prescriptivists claim that there are certain rules which have authority over us even if they are not respected as correctness conditions in the ordinary usage of anybody. You can tell them, "All writers of English sometimes use pronouns that have genitive noun phrase determiners as antecedents; Shakespeare did; Churchill did; Queen Elizabeth does; you did in your last book, a dozen times" (see here and here for early Language Log posts on this); and they just say, "Well then, I must try even harder, because regardless of what anyone says or writes, the prohibition against genitive antecedents is valid and ought to be respected by all of us." To prescriptivists of this sort, there is just nothing you can say, because they do not acknowledge any circumstances under which they might conceivably find that they are wrong about the language. If they believe infinitives shouldn't be split, it won't matter if you can show that every user of English on the planet has used split infinitives, they'll still say that nonetheless it's just wrong. That's the opposite insanity to "anything that occurs is correct": it says "nothing that occurs is relevant". Both positions are completely nuts. But there is a rather more subtle position in the middle that isn't. That is the interesting and conceptually rather difficult truth that Zink does not perceive.

[You'll see that there's now lots more discussion available courtesy of ceejbot. There you can have the pleasure of seeing me described as "an abyssmal [sic] dunce" (for not believing that which is limited to supplementary relative clauses in Standard English). You'll read that I'm "a liar"; "smugly superior"; "muddled"; and someone who "thinks his judgement counts more than everyone else's". The strange thing about this kind of commentary is that while I stress (above) that it is entirely possible for a linguist to be wrong about what the correctness conditions on a language (even their own language) really are, the people calling me smug, stupid, and mendacious have no doubts whatsoever. They seem utterly convinced of their rectitude, as they angrily attribute to me the exact opposite of what I said. For example, you'll see that Scholz and I are directly accused (by a user called Nick) of holding that "correct" means "what happens". Our actual view is that we firmly and explicitly deny that, though we also resist the opposite lunacy, the position that what happens has no relevance to the determination of what's correct. As Mark pointed out to me when he first referred me to ceejbot, it's not just the the existence of ignorant authoritarian prescriptivism in this culture that needs an explanation, it's also the level of anger that accompanies its expression.]

Now about those facts ...

Early in the President's press conference this morning, G.W.B. was asked about a case of a Jordanian man who was jailed for speaking out against his government. The reporter's question was: will G.W.B. publically condemn this man's punishment as anti-democratic, even though it was performed by an ally of the United States? Claiming not to know anything about the case, G.W.B. said:

You're asking me to comment on something (that) I do not know the facts.

The "that" is in parentheses because he repeated this same sentence twice, once with the "that" and once without. (Well, more or less the same sentence; he may have said "don't" instead of "do not" one of those times, and the main clause of the sentence may have been worded a tiny bit differently each time.)

Is this a case of hypercorrective avoidance of a sentence-final preposition (in this case, about)? As a faux-bubba speaker (Geoff Nunberg's term), G.W.B. is unlikely to say "... something about which I do not know the facts", but clearly (to me, at least), he finds something wrong with "... something (that) I do not know the facts about"; my interpretation of the situation is that G.W.B. avoided the problem by just not pronouncing the (otherwise obligatory) preposition.

|

Update: Andy Grover writes:

That certainly is a possibility. Finding myself with some free time at the espresso machine here at Language Log Plaza, I went to www.whitehouse.gov and re-listened to the relevant portion of the press conference. Here are the sound clips.

Just speaking as a speaker of (what I think is) the same language, the intonation of the first clip is inconsistent with Andy's hypothesis. However, I'm less sure about the second clip now (which is why I gave it more of the surrounding context). It's entirely possible that the relevant bit of the quote should be punctuated thusly: you're asking me to comment on something; I do not know the facts -- in which case, Andy's hypothesis would be right. Now back to my espresso ... mmm, dee-lish. |

[ Comments? ]

CRF bibliography

Hanna Wallach has posted a terrific annotated bibliography (with links to all the papers, of course) on Conditional Random Fields. Her blog is join-the-dots, where you'll find lots of other neat stuff.

More arithmetic problems at Google

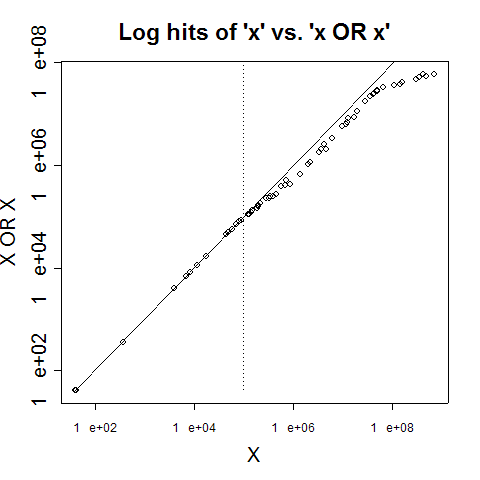

Jean Véronis has some further observations and speculations about Google counts. He discovers another experimental situation in which there's apparently a large bias that increases with the size of the counts. I saw something similar earlier in the ratio of {X OR X} to {X} counts; Jean finds a systematic and increasing error in comparing counts in English pages to counts in all pages. As Jean points out, in both experiments there's a sort of phase change at counts of around 0.5x108.

So to the earlier piece of advice ("be careful about counts much greater than 100K") we can add another one ("pay no attention at all to counts above about 500M"). Or if you care about counts, use Yahoo, which (at least for the experimental situations examined) doesn't show these weird errors.

I don't entirely agree with Jean's characterization of the situation, however. He seems to feel that if "the real index on which the data centers are operating [is] be much smaller, and in such a case an extrapolation would be done", that this would constitute "faking" the counts. I think this is quite unfair, because I don't see how it could be any other way. There's simply no way that Google -- or Yahoo or any other search provider -- could service every query involving more than one search term by doing a full intersection of sets of results that might be counted in the hundreds of millions or even billions. They will often have no choice but to "do a prefix and then extrapolate", as my correspondent from Google put it. The issue is how accurate the extrapolation is. And at the moment, Google's extrapolation clearly sucks.

At least this is true in the experimental circumstances that Jean and I have tested, and for cases where large sets of results are involved. Given these findings, my belief Google's counts (for queries involving more than one term or other search condition) starts at about 0.9 when sets of about 100K pages are being combined, and falls monotonically to zero as the set size increases to 500M.

I doubt that this matters at all to most of Google's users, who want the relevant pages, not the counts. But I'm sure that Google's (smart, honest and dedicated) researchers and programmers will fix the problem anyhow.

Posted by Mark Liberman at 09:42 AM

A Series of Unfortunate Events

On Friday, I'm giving a talk at Stanford entitled "A series of unfortunate events: the past 150 years of linguistics".

Here's the abstract:

About ten years ago, a publisher's representative told me that introductory linguistics courses in the U.S. enroll 50,000 students per year, while introductory psychology courses enroll about 1,500,000, or 30 times more. The current number of Google hits for "linguistics department" is 60,900, while "psychology department" has 1,010,000, or 14 times more. The Linguistic Society of America has about 4,000 members, while the American Psychological Association has more than 150,000 members, or about 38 times more. Comparisons between linguistics and fields like history or chemistry give similar results.

It's easy to accept this state of affairs as natural, but in fact it's bizarre, both historically and logically. Furthermore, it's part of a larger and much more serious problem. Those who are resigned to the fate of our academic discipline should still be disturbed that contemporary intellectuals are taught almost no skills for analyzing the form and content of speech and text, or that reading instruction is so widely based on false or nonsensical ideas that a quarter of all students have difficulties serious enough to interfere with the rest of their education.

To break the grip of familiarity, it may help to view the past 150 years of intellectual history as a poker game. We began with a bigger stake than almost anyone else at the table, and have been dealt a series of very strong hands. However, our field is now a marginal player, in danger of being busted out of the game entirely.

In this talk, I'll review our unfortunate past, and discuss the prospects for a brighter future.

Glen Whitman may see this as further evidence of psychological rent-seeking:

I constantly encounter people who think their own career or field of study is the most important one in the world. Educators teach us that education is underappreciated and underfunded. Public health officials diagnose us with insufficient concern for health and inadequate policies to make us take it more seriously. People in the arts sing a tune about the vast significance of music, theater, painting, and sculpture for the human psyche. The linguists at Language Log wax eloquent about the need for more and better linguistic education.

Economists are not immune to the syndrome, but I think they are somewhat more resistant. Of course, economists regularly complain about people – especially journalists – who opine about economic issues with hardly a rudimentary understanding of the subject. (That, to be fair, is often the linguists’ complaint as well: that people who know almost nothing about linguistics so often fancy themselves experts on language.) Still, I rarely find economists talking about how everyone should be forced to obtain, and others be forced to fund, an education in economics. Why not?

Well, uh, could it be that it's because at most universities, in many disciplines, many "others are forced to obtain" (or at least very strongly urged or even constrained to obtain) an education in economics? For example, at my own institution, all 1,500 Wharton undergraduates are required to take the basic economics sequence from the econ department, and requirements in a half a dozen other majors are set up so as to encourage students to learn economics. That's all to the good, in my opinion -- but the result is that economists here are more likely to be worried about how to keep enrollments down to manageable levels, than to be talking about how to encourage more students to learn their discipline. This is not simply the results of intellectual "market forces" -- it happens because of formal structures of requirements and listed options, and also because of well-established informal patterns of advising.

You may be saying to yourself "duh, of course students in a business school need to learn economics; and how could you hope to understand political science or sociology or philosophy or anthropology without having the concepts and methods of economics in your intellectual toolkit?" And you'd be right. But as a point of comparison, let's consider the role of linguistics and language analysis in the discipline known as "English".

In the domain english.stanford.edu, Google finds seven instances of the word "linguistics" (I just checked because I wanted a bit of exemplification for my talk).