December 31, 2005

Pointers, References, and the Rectification of Names

Mark's discussion of Joel Spolsky's rant about young programmers who haven't learned C and Scheme provides a probable example of a real effect of language on the way we think, though one that is not usually considered part of the Sapir-Whorf effect. To recap, Spolsky argues that programmers who learn C learn about pointers and the data structures that can be built with them, such as linked lists and hash tables, while those who learn Java do not learn about pointers and therefore do not learn about such data structures. Mark and an unnamed Penn computer science faculty member whom he quotes take the position that Java does have pointers and that students taught using Java do learn about data structures like linked lists.

Spolsky is right in saying that Java does not have pointers. In the now standard usage in discourse about programming languages, Java is said to have references but not pointers. The Wikipedia articles on pointers and references treat pointers as a particular type of reference and explicitly state that Java has a kind of reference but not pointers. Similarly, Java in a Nutshell, which in spite of its name is, at 969 pages, a reference manual, in the enormously popular and often authoritative O'Reilly series, contrasts C pointers with Java references thus at p. 75:

It is very important to understand that, unlike pointers in C and C++, references in Java are entirely opaque: they cannot be converted to and from integers, and they cannot be incremented or decremented.

It is true that some people use pointer in a broader sense more-or-less equivalent to reference, so the distinction made above is not universal. I think that it is fair to say that when people are talking seriously about programming language design they generally do make this distinction.

On the other hand, Spolsky is wrong in thinking that Java's lack of pointers prevents Java from being used to build the kinds of data structures for which pointers are used in C. Here's a little Java program illustrating the use of linked lists constructed using references. The first three lines tell us that an object of class link consists of a string and a reference to an object of class link. The fourth through eighth lines define a constructor method for links, that is, a function that creates new instances of the class. The remainder is a program that illustrates the use of linked lists.

public class link {

public String value;

public link next;

public link(String s, link ln)

{

value = s;

next = ln;

}

public static void main(String args[])

{

link head = null;

//Insert command line arguments into list

for (int i = 0; i < args.length; i++) {

head = new link(args[i], head);

}

//Write out the list

link p = head;

while (p != null) {

System.out.print(p.value);

System.out.print(' ');

p = p.next;

}

System.out.print('\n');

}

}

This program creates a linked

list of the strings passed on the command line, then prints them out

starting at the head of the list. Since it inserts each new node at the head of the

list, the strings are printed out in the reverse order in which they are supplied

on the command line. If, for example, you execute this program with the command

line (after first compiling it, in my case with: javac link.java):

java link cat dog elk fox

it will print:

fox elk dog cat

Linked lists such as this are one of the data structures that Spolsky claims that you don't get experience with in Java. He's right that it is important for students of computer science to learn about them; he's wrong in thinking that Java doesn't support them.

So, where did Spolsky go wrong? It is possible that he just doesn't know that there are kinds of references other than pointers or doesn't know that Java has them, but I suspect that he fell victim to reasoning on the basis of the names of things rather than their properties, something like this:

- Pointers are used to construct data structures like linked lists.

- Java lacks pointers.

- Therefore one cannot create data structures like linked lists in Java.

The flaw is in the unstated inference from the proposition that pointers are used to construct linked lists in C, which is true, to the proposition that one must have pointers in order to construct linked lists, which is false. References are sufficient, if you have them. Of course, since C has only pointers, not references, it is true that in C you can't create linked lists without pointers. One of the ways in which language is useful is that we can rememember the names of things rather than their properties, but this carries with it the danger of falsely attributing properties to things based on their names.

The anonymous Penn computer science faculty member whom Mark quotes makes another invalid argument from language in using the existence in Java of an exception called a NullPointerException as evidence that Java has pointers. This exception is misnamed - it really should be NullReferenceException. This exception is thrown on an attempt to access a field or call a method of a null object, and the null value is of type reference. The people who designed Java knew C and intended references to be a safer way of doing most of the things that are done with pointers in C, so they inadvertently used the term pointer in naming this exception, but that doesn't change the fact that it is an exception thrown on illegal use of a reference, not a pointer.

This sort of erroneous reasoning has been recognized for a long time. One of the central doctrines of Confucian philosophy, the 正名 "Rectification of Names", is concerned with the false reasoning to which misleading names can lead. Here is the famous passage (13.3) from the 論語 Analects on the importance of the rectification of names:

子路曰: 衛君待子而為政,子將奚先?

子曰: 必也正名乎!

子路曰:有是哉?子之迂也!奚其正?

子曰: 野哉,由也!君子於其所不知,蓋闕如也。名不正,則言不訓;言不訓,則事不成;事不成,則禮樂不興;禮樂不興,則刑罰不中;刑罰不中,則民無所措手足。故君子名之必可言也,言之必可行也。君子於其言,無所茍而已矣![You can find the complete text here. Incidentally, when in search of Chinese language resources, I recommend Marjorie Chan's magnificent ChinaLinks.]

Those whose classical Chinese is rusty may find Legge's translation helpful:

Tsze-lu said, "The ruler of Wei has been waiting for you, in order with you to administer the government. What will you consider the first thing to be done?"

The Master replied, "What is necessary is to rectify names."

"So! indeed!" said Tsze-lu. "You are wide of the mark! Why must there be such rectification?"

The Master said, "How uncultivated you are, Yu! A superior man, in regard to what he does not know, shows a cautious reserve. If names be not correct, language is not in accordance with the truth of things. If language be not in accordance with the truth of things, affairs cannot be carried on to success. When affairs cannot be carried on to success, proprieties and music do not flourish. When proprieties and music do not flourish, punishments will not be properly awarded. When punishments are not properly awarded, the people do not know how to move hand or foot. Therefore a superior man considers it necessary that the names he uses may be spoken appropriately, and also that what he speaks may be carried out appropriately. What the superior man requires is just that in his words there may be nothing incorrect."

December 30, 2005

Opa!

I'm in New York for the American Philosophical Association's Eastern Division meetings, and I'm having breakfast at the Art Cafe on Broadway, at 52nd Street. It's all bustling efficiency, staff zooming hither and thither. Two eggs up with bacon and wheat toast arrive within a couple of minutes. Suddenly there's a shattering crash from behind the counter, and the Greek proprietor is looking down mournfully at the coffee cup he dropped on the tile floor to smash into a thousand pieces. Four or five nearby waitresses turn in shock. For two seconds of silence they stare at the scene of the accident. And then one of the waitresses yells excitedly: "Opa!" — the traditional Greek cry of encouragement to dancers and musicians and drinkers at those wild parties where they smash plates on the floor as they dance just to show what a great time is being had. And then the entire staff cracks up, and they all resume working at high speed, but now laughing till tears come to their eyes — the boss included. It's only breakfast time in New York, but already, thanks to one well-chosen interjection, it's like a party.

Old school

Joel Spolsky demonstrates what he calls his "descent into senility" in a classic "kids these days" rant, about how today's programming courses are too easy because they use Java. He sums it up at the end with a version of the old joke,

A: In my day, we had to program with ones and zeros.

B: You had ones? Lucky bastard! All we got were zeros.

On his way to the punch line, he tells us "Java is not, generally, a hard enough programming language that it can be used to discriminate between great programmers and mediocre programmers". This is in contrast to the old-school courses based on Scheme and C, whose difficulty Spolsky remembers as "astonishing". Spolsky "struggled through such a course, CSE121 at Penn". He tells us that he "watched as many if not most of the students just didn't make it. The material was too hard. I wrote a long sob email to the professor saying It Just Wasn't Fair. Somebody at Penn must have listened to me (or one of the other complainers), because that course is now taught in Java."

Now he wishes that my colleagues in computer science at Penn hadn't listened to him, because he feels that today's Java-based courses don't teach about pointers (which are a central issue in C programming) and recursion (which is central in Lisp). And according to him,

beyond the prima-facie importance of pointers and recursion, their real value is that building big systems requires the kind of mental flexibility you get from learning about them, and the mental aptitude you need to avoid being weeded out of the courses in which they are taught. ...

Nothing about an all-Java CS degree really weeds out the students who lack the mental agility to deal with these concepts.

He compares this to the gatekeeper function once played by Latin and Greek:

... in 1900, Latin and Greek were required subjects in college, not because they served any purpose, but because they were sort of considered an obvious requirement for educated people. In some sense my argument is no different that the argument made by the pro-Latin people (all four of them). "[Latin] trains your mind. Trains your memory. Unraveling a Latin sentence is an excellent exercise in thought, a real intellectual puzzle, and a good introduction to logical thinking," writes Scott Barker. But I can't find a single university that requires Latin any more. Are pointers and recursion the Latin and Greek of Computer Science?

I suspect that the "Latin trains your mind" argument became prominent just when the real practical reasons for a grounding in classical languages had largely vanished, and when obligatory teaching of Latin was therefore under successful attack. In the seventeenth century, an educated person needed to know Latin in order to read the current literature: Newton's Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica was published in Latin in 1687, and was not translated into English until 1729. But long before 1900, it was difficult to find practical arguments for the role of Latin in career development, outside of Catholic theology and a few areas of history and literature. Latin (and to a lesser extent Greek) had been reduced to the status of a cultural common ground for (the more traditionally-minded strata of) the educated and professional classes, and a barrier to entry into those strata.

And just as Spolsky was wrong in 1987 if he believed that it was the use of Scheme in Penn's CSE 121 that made it too hard, he's wrong now to complain that the use of Java means that such courses now necessarily fail to ground students in foundational concepts such as pointers and recursion. A colleague who has recently taught that course writes:

This is total BS. Java has pointers (has Spolsky ever heard of NullPointerException?), and we spend a lot of time on recursion and data structures, and very little time on OOP terminology. It also demonstrates the cult attitude of a certain kind of programmer, with rites of passage, the chosen and the fallen, etc. We teach in Java because it is the best compromise for a set of conflicting requirements. It's only people who can't teach who rant on about "pure" approaches. Reminds me of a certain kind of academic "radical" activist of my youth.

Well, in fairness to Spolsky, he does lead with a jokey admission that he's descending into senility, and he quotes from the start of Monty Python's Four Yorkshiremen skit:

“You were lucky. We lived for three months in a brown paper bag in a septic tank. We had to get up at six in the morning, clean the bag, eat a crust of stale bread, go to work down the mill, fourteen hours a day, week-in week-out, and when we got home our Dad would thrash us to sleep with his belt.”

(And do read the rest of it, if you haven't done so recently.)

I went to a secondary school where Latin was still required, and I think that I benefited from it. However, that's mainly because grammar, logic and rhetoric are a good foundation for a general education, and careful analysis of admired works in a foreign language is a good way to provide that foundation. My objection to language education today is not that schoolchildren are no longer required to learn Latin, but that most of them are no longer taught linguistic analysis of any sort at all.

I suspect that there's a similar basis for Spolsky's frustration at the quality of job applicants that happen to be coming his way these days. If they can't "rip through a recursive algorithm in seconds, or implement linked-list manipulation functions using pointers as fast as they could write on the whiteboard", it's because they haven't learned the relevant concepts and skills, not because their intro programming courses didn't use LISP and C.

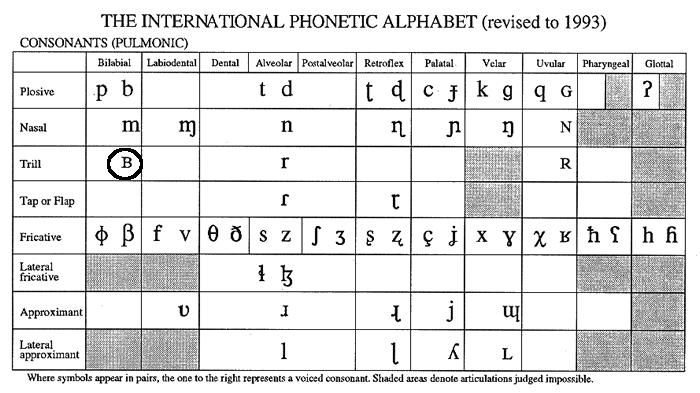

Senility and Monty Python jokes aside, there are some serious and important educational issues here. But it just confuses matters to focus on Scheme and C or Latin and Greek, instead of on pointers and recursion or IPA and parsing.

[I guess I should add that other undergraduate computer science courses at Penn require the use of other languages, including not only Scheme and C/C++, but also OCaml, Prolog, Python and Matlab, depending on what makes sense for the content and structure of the course in question. I believe that this is typical of good computer science programs in the U.S. these days. ]

[Update 1/9/2006: Since some people are still linking here, I'll add a link to a thoughtful post by a current Penn undergrad, and to Bill Poser's terminological disquisition.]

How often does your mother say "butt"?

So asks Benson Smith, proposing a novel and interesting hypothesis that may shed new light on the contested origins of the phrase "butt naked":

Your post "new intensifiers" was linked recently from a German/English translation forum I like to read. I thought you might enjoy my pet theory:

1) in German, the word "aber" is used as an intensifier in the same way (es ist ABER kalt! = it's REALLY cold!)

2) "aber" is...wait for it...German for "but"

3) there have been a lot of German settlers in America, including, for example, Iowa

4) my mother, who is from Iowa, occasionally says "it is *but(t)* cold outside"

5) how often does your mother say "butt"?Conclusion: the expression was originally "but X" -- but cold, but ugly, etc. It comes from German settlers speaking English too literally. Naturally, native English speakers misinterpreted "but" as "butt", since "but" is not used as an intensifier in English.

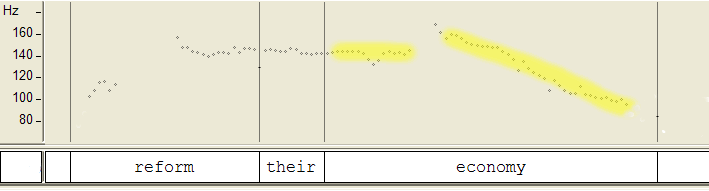

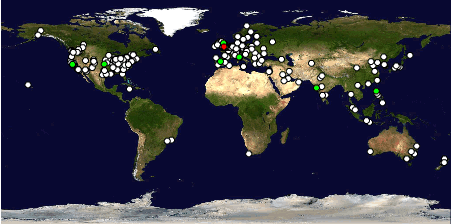

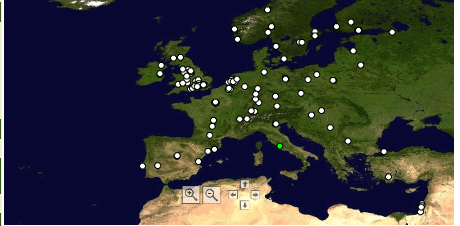

Well, this morning Google does have 908 hits for {"butt cold"}. Unfortunately, Google Maps won't yet let us display an overlay of dots for the native region of the authors -- or even for the geographical location of the IP addresses of the sites, like these maps of recent Language Log visitors (produced by sitemeter, not by Google):

More seriously, one of the things I've come to realize about this sort of etymological discussion is that there may sometimes be more than one right answer. Ben Zimmer has promoted Alan Metcalf's five FUDGE factors for predicting the success of neologisms (Frequency of use, Unobtrusiveness, Diversity of users and situations, Generation of other forms and meanings, and Endurance of the concept), adding his own sixth factor Resistance to public backlash. This gives us FUDGER, and I don't see any graceful way to add another pronounceable letter (maybe fudgery?), so I'll give up on the acronymic theme, and just add my suggestion in plain prose.

Multiple sources, interpretations and resonances increase the fitness of a word or phrase. Regionalisms, archaisms, technical terms, substrate influences and euphemistic (or scatalogical) alternatives can all help. Whatever and whenever the earliest uses of "butt naked" and "buck naked" were, it seems clear that both have been around for a while, with plausible independent modes of interpretation, connected to some of the ordinary meanings of butt and buck. There might also have been some support from a calque representing common usage in German, the non-English language spoken by the largest number of immigrants to the U.S. over the course of its history. I haven't seen any real evidence for this theory -- with all due respect to Benson Smith's mother -- but evidence that the intensifier sense of butt has other roots is not necessarily evidence against his suggestion. And vice versa.

From Nabisco to NaNoWriMo

In my post yesterday critiquing Kevin Roberts' coinage of sisomo (an acronymic blend of "sight, sound, and motion"), I stated that "extracting the first two letters from each word in a series is not a productive source of English neologizing." This was a bit too glib a dismissal, since there is some precedent for such orthographic blends, especially if we consider not just two-letter "Consonant-Vowel" components but the combination of initial syllables or syllable-parts more broadly.

The birth of modern English acronymy can be traced to the early years of the 20th century (though there is some evidence for acronymic thinking — mainly in the form of backronyms — from the 19th century and earlier). In 1901, the National Biscuit Company filed a trademark for a shortened form of the company name: Nabisco. The following year (as noted by David Wilton on the American Dialect Society mailing list and in his book Word Myths), Sears, Roebuck & Company began advertising under the trade name Seroco. Similar corporate acronyms quickly followed, particularly in the petroleum business. In 1905, the Texas Company sought a trademark for Texaco, and other oil companies such as Sunoco (Sun Oil Company), Amoco (American Oil Company), and Conoco (Continental Oil Company) followed suit by the 1920s. The shared component in these blends is the final -co, short for company in all cases. (It could even appear medially, as in Socony, for Standard Oil Company of New York). This is clearly derived from the abbreviation Co., which developed a spelling pronunciation of /koʊ/ (independent of the pronunciation of the first syllable of /'kʌmpəni/) that was then available for acronymic combination. We can see a similar process with other abbreviation-derived components, such as So. and No. in acronyms like SoCal (Southern California) and NoCal (Northern California).

Seroco and all of those oil companies ending in -oco must have exerted an influence on English speakers' acronymic patterning, since we find a marked propensity towards orthographic blends involving rhyming -o syllables throughout the late 20th century. In the mid-1960s, the Howard Johnson restaurant chain came to be known as HoJo or HoJo's (evidently popularized by the introduction of "HoJo Cola" in 1964). It would then be the fate of anyone named Howard Johnson, be he a New York Met or president of MIT, to be assigned the nickname HoJo. On the HoJo model, track star Florence Griffith-Joyner was popularly known as FloJo when she won three gold medals at the 1988 Olympics. Similar rhyming nicknames continue to develop, such as ProJo for the Providence (R.I.) Journal and more recently MoDo for New York Times columnist Maureen ("Mo") Dowd (used as early as Sep. 2002 by Andrew Sullivan).

Since the 1970s, blends à la HoJo have extended beyond personal nicknames. The region of lower Manhattan below Houston Street was originally known as "South Houston Industrial Area," but this was shortened by city planners to the snappier SoHo around 1970. The new name was interpreted as a blend of "south of Houston" and was soon joined by NoHo ("north of Houston"), not to mention various other non-rhyming blend-names for Manhattan neighborhoods (TriBeCa, NoLiTa, etc.). Other acronymic legacies of the 1970s include slomo for "slow-motion" and froyo for "frozen yogurt" (though these at least match up phonemically with the source material, unlike the other strictly graphemic blends discussed here). The 1980s of course brought us pomo for "post-modern(ist)" approaches to art and literature. And in 2000, David Brooks introduced his own contribution to the field in the title of his book Bobos in Paradise, where bobo stands for "bourgeois bohemian" (in turn apparently modeled on the old shortening of bohemian to boho).

No other vowel comes close to o in the production of rhyming orthographic blends. The only serious competitor is i, largely on the strength of two popular coinages from the mid-20th century: hi-fi for "high fidelity" (appearing as early as 1947 in an issue of Popular Science Monthly uncovered by Barry Popik) and sci-fi for "science fiction" (dated to 1949 in a letter by Robert Heinlein tracked down by Jeff Prucher of the Science Fiction Citations project). More recently we have Wi-Fi, which many assume stands for "wireless fidelity" on the analogy of hi-fi. But Phil Belanger, a founding member of the Wi-Fi Alliance, recently revealed that Wi-Fi wasn't originally intended to stand acronymically for anything (though obviously there must have been an implicit modeling on hi-fi).

Note that hi-fi and sci-fi both use the /aɪ/ pronunciation for the letter i, which phonemically matches each blend's first component (high and science, respectively). The second syllable (fi in both cases) follows with /aɪ/, despite the fact that the i in the first syllables of fidelity and fiction are actually pronounced as /ɪ/. This is for the sake of the rhyme, but also because the rules of English phonotactics disallow words ending in /-Cɪ/. (The schwa sound /ə/ is available word-finally, so presumably hi-fi could have ended up sounding like Haifa. But the rhyme was clearly too appealing to early hi-fi enthusiasts.)

So how does Roberts' creation of sisomo stack up to these neologistic forebears? The final two syllables with their matching o's don't seem so bad, especially since there are precedents for using so to stand for sound (as in sonar) and mo to stand for motion (as in slomo). But that first syllable — si for sight — is still rather odd, since Roberts wants us to pronounce it as /sɪ/ (based on the synthesized voices that keep obtruding on his website). Why not /saɪ/, which would not only match up phonemically with sight but would also resonate with earlier blends like hi-fi and sci-fi ? Odder still, when we hear the creator himself pronounce the word by clicking on "Kevin Roberts' message" on the site, he's pronouncing it with initial-syllable stress as /'sɪsəmoʊ/, which both draws attention to the clumsy first component and destroys the euphony one would expect from rhyming o's. (Roberts, by the way, is a New Zealander working in New York for a London-based firm, so his speech pattern has a certain "International English" flair to it.)

Finally, I should note that what I sense as artificial and awkward in sisomo might actually work for other pairs of ears. On Erin O'Connor's LiveJournal blog there has been a lively debate on the coinage, with most commenters objecting on semantic grounds or a general impression of "yuckiness." But one contributor mentioned a recent acronymic blend that strikes me as structurally quite similar to sisomo: NaNoWriMo, which stands for "National Novel Writing Month." Since the launch of NaNoWriMo in 1999, companion blends have appeared like NaNoEdMo (National Novel Editing Month), NaNoWriYe (National Novel Writing Year), and NaNoPubYe (National Novel Publishing Year). So perhaps this type of acronymic pile-up really is the wave of the future and I'm just being a stick in the mud. I probably would have griped about Nabisco in 1901.

[Update #1: Jeff Russell emails with some examples of "Stanford-speak":

Your Language Log post on initial-syllable acronymy struck a chord with me, since it's particularly prevalent at my recent alma mater Stanford University, where this pattern is referred to as "Stanford-speak". Some words are rolled out mostly during admit weekend (usually referred to as "ProFro weekend", from "prospective freshman") and feel artificial even to us undergraduates, but most of these words are used without any self-consciousness by mid-freshman year. In fact, it would garner strange looks or confusion to refer to the CoHo as "the coffee house", to the dorm FloMo as "Florence Moore", or to FroSoCo as "Freshman-Sophomore College". "Memorial Church" is MemChu, "Memorial Auditorium" is MemAud, "Tresidder Express" is TresEx, and "Residential Education" is ResEd. In writing, these appear with our without spaces, and with or without the capital letters.

As you observed, rhyming -o syllables, are particularly common, even to the point of co-opting other vowels (though the "fro" in "freshman" may arise from "frosh"). One interesting thing is that attempts to coin new Stanford-speak--and they are often made--usually fail. "MuFuUnSun" (for Music and Fun Under the Sun, an annual event) and "HooTow" (for Hoover Tower), while in use, never sound anything but contrived, and most (like "FoHo" for fountain-hop, or "StanSpe" for Stanford-speak) are non-starters. ]

[Update #2: Jonathan Epp writes in with another NaNoWriMo spinoff and a question about the pronounceability of such acroblends:

I had seen NaNoWriMo used in blogs before your "From Nabisco to NaNoWriMo" post, but had never imagined that anyone would actually say it verbally. (Although, that may say more about the circle of people I speak with than anything else.) I've also seen NaDruWriNi (National Drunk Writing Night) used in blogs, which would seem even more awkward to use in conversation. Given the context though, that may be half the fun. ]

December 29, 2005

Asbestos she can

A few days ago, Nathan Bierma asked me (by email) whether the construction exemplified by "as best (as) I can" might be a blend of "the best (that) I can" and "as well as I can". The puzzle is why we say "as best (as) I can", but not "as hardest (as) I can", or indeed "as ___ (as) I can" for any other superlative.

Whatever the exact history, "as best <SUBJ> <MODAL>" is an old pattern. For instance, an anonymous drama from 1634, "The Mirror of New Reformation", has the lines

... I wil straight dispose,

as best I can, th'inferiour Magistrate ...

And in "The Taming of the Shrew" (1594), Shakespeare has Petruchio say

And I haue thrust my selfe into this maze,

Happily to wiue and thriue, as best I may ...

The pattern "as best as" seems to be more recent. The earlier citation I could find was from 1856, in "Night and Morning" (a play adapted from the novel by Bulwer-Lytton), where Gawtry says:

In fine, my life is that of a great schoolboy, getting into scrapes for the fun of it, and fighting my way out as best as I can!

It continues to be used by reputable authors, as in William Carlos Williams' poem 1917 poem "Sympathetic Portrait of a Child":

As best as she can

she hides herself

in the full sunlight

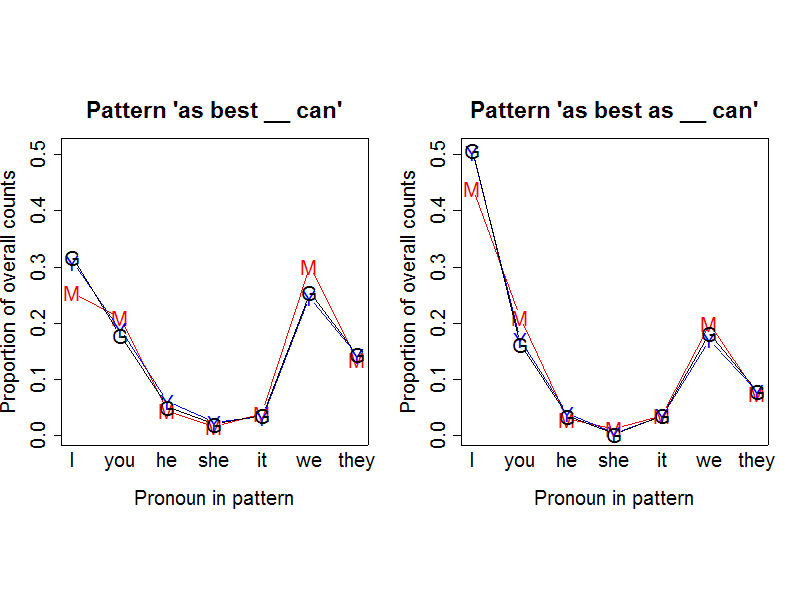

But whatever the origins and history of the construction, Nathan's suggestion might have something to do with the forces that keep it in current use. So I thought I'd look at some current web counts; and since different search engines sometimes give counts that differ in random-seeming ways, I tried MSN, Yahoo and Google. I started by looking at the patterns "as best __ can" and "as best as __ can", across the different pronouns. I might still discover something relevant to Nathan's question, but along the way I stumbled on a strange pattern in the web search count, which I'll share with you now.

| [MSN] | I |

you |

he |

she |

it |

we |

they |

[total] |

| as best __ can | 183,672 |

152,044 |

31,785 |

11,353 |

28,837 |

217,952 |

98,167 |

|

| as best as __ can | 74,551 |

35,688 |

4,869 |

1,938 |

6,133 |

33,812 |

12,724 |

|

| best/best as ratio | 2.4 |

4.3 |

6.5 |

5.9 |

4.7 |

6.4 |

7.7 |

4.3 |

| [Yahoo] | I |

you |

he |

she |

it |

we |

they |

[total] |

| as best __ can | 1,070,000 |

659,000 |

210,000 |

80,300 |

114,000 |

853,000 |

495,000 |

|

| as best as __ can | 438,000 |

148,000 |

33,400 |

2,800 |

30,300 |

148,000 |

67,500 |

|

| best/best as ratio | 2.4 |

4.5 |

6.3 |

28.7 |

3.8 |

5.8 |

7.3 |

4.0 |

Helpful Yahoo asks "Did you mean 'asbestos they can'?", although the suggested substitution gets only 95 yits compared to 67,500 for "as best as they can", andYahoo doesn't make any such suggestion for any of the other pronouns in this pattern.

| [Google] | I |

you |

he |

she |

it |

we |

they |

[total] |

| as best __ can | 830,000 | 466,000 | 132,000 | 51,000 | 95,100 | 667,000 | 377,000 | |

| as best as __ can | 320,000 | 102,000 | 21,600 | 851 | 22,400 | 114,000 | 49,300 | |

| best/best as ratio | 2.6 | 4.6 | 6.1 | 60.0 | 4.2 | 5.9 | 7.6 | 4.2 |

In this case, the (proportional) counts are generally pretty consistent across the search engines:

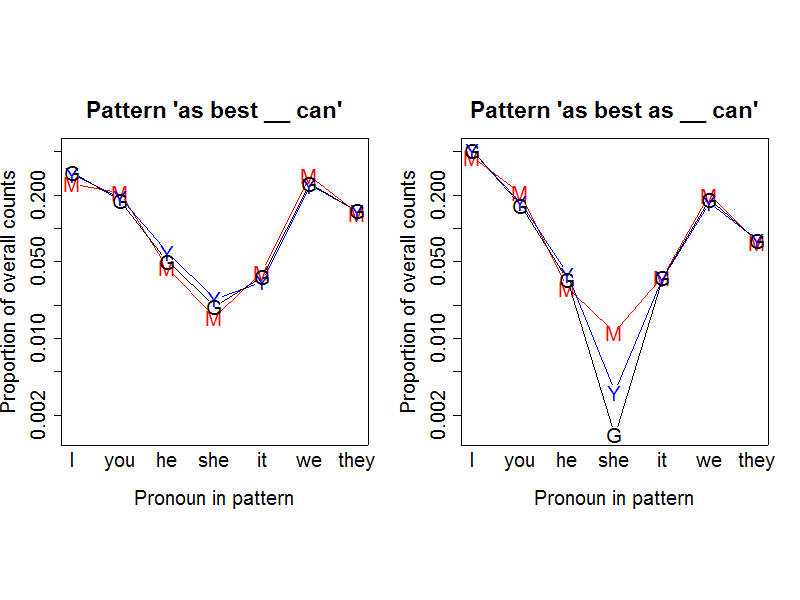

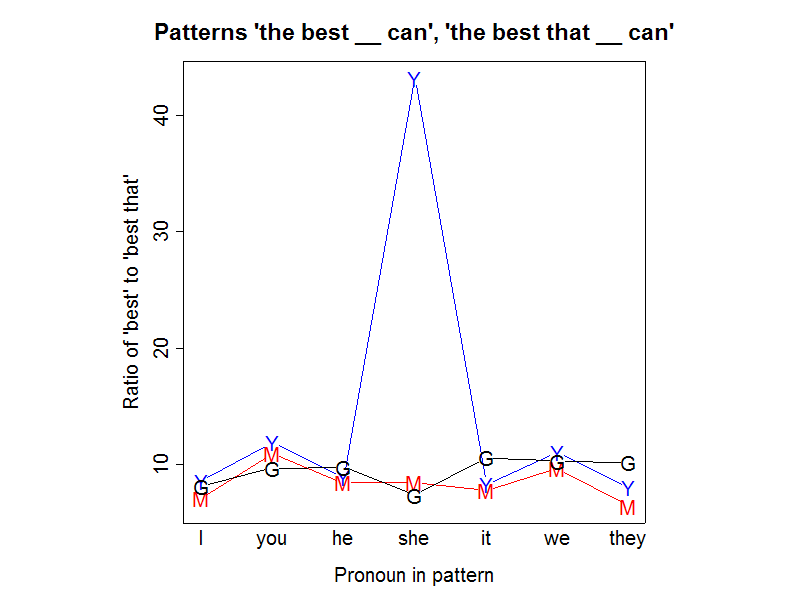

However, there's something funny going on with "she", as we can see better if we display the proportions on a log scale:

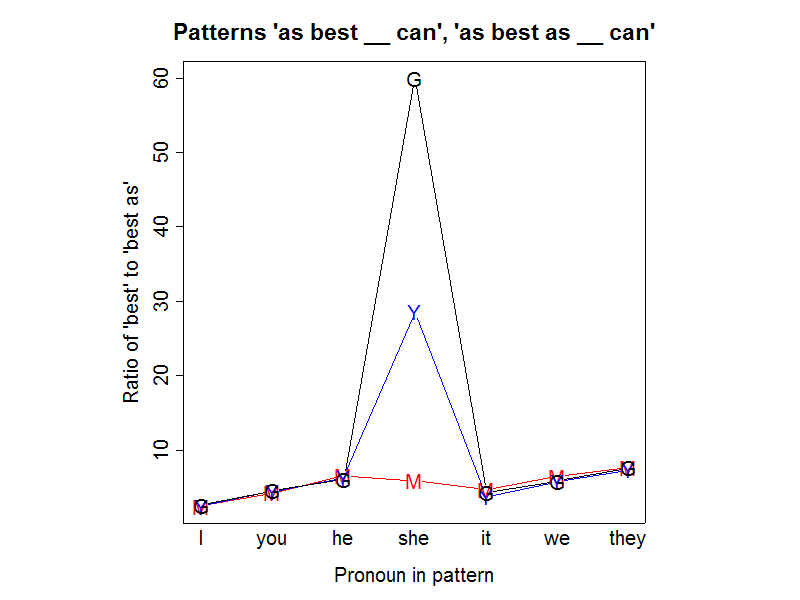

The oddity is even clearer if we plot the best/best as ratios:

Google and Yahoo have many fewer hits for the string "as best as she can" than they ought to, in proportion to their counts "as best she can" and their counts for other pronouns in both patterns. What could be going on?

If all three search engines showed the same deficit, we might explore the idea that this is telling us something about our culture's thought and language. But they don't, and so I strongly suspect that instead this is showing us something about the algorithms that Google and Yahoo use to prune SEO-blackhat web pages.

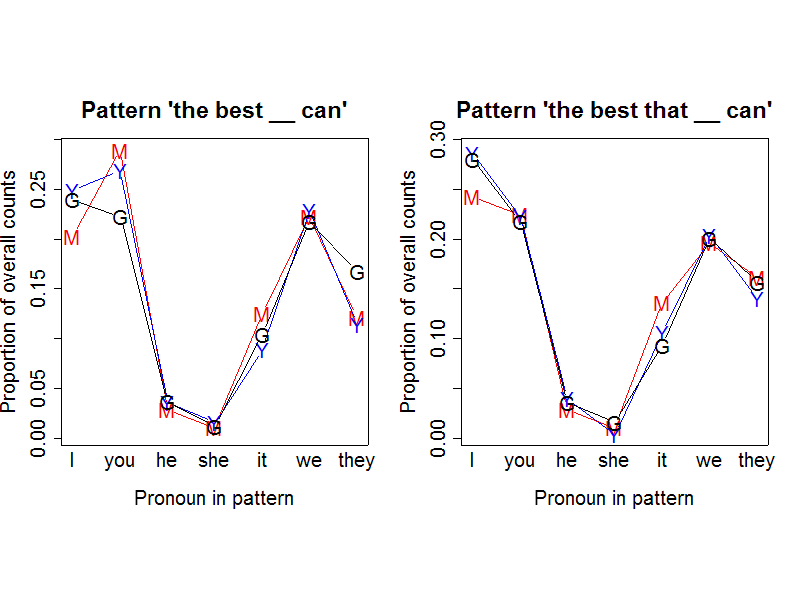

For linguistic as well as algorithmic comparison, here are the analogous numbers and pictures for the pattern "the best (that) __ can":

| [MSN] | I |

you |

he |

she |

it |

we |

they |

[total] |

| the best __ can | 462,164 | 659,558 | 65,128 | 23,822 | 284,798 | 508,639 | 277,363 | |

| the best that __ can | 64,998 | 60,047 | 7,715 | 2,812 | 36,476 | 52,614 | 43,164 | |

| best/best as ratio | 7.1 | 11.0 | 8.4 | 8.5 | 7.8 | 9.7 | 6.4 | 8.5 |

This time, by the way, helpful MSN asks "Were you looking for 'the beast that we can'?"

| [Yahoo] | I |

you |

he |

she |

it |

we |

they |

[total] |

| the best __ can | 2,940,000 | 3,180,000 | 422,000 | 183,000 | 1,050,000 | 2,700,000 | 1,350,000 | |

| the best that __ can | 343,000 | 267,000 | 47,300 | 4,240 | 127,000 | 244,000 | 168,000 | |

| best/best as ratio | 8.6 | 11.9 | 8.9 | 43.2 | 8.3 | 11.1 | 8.0 | 9.8 |

| [Google] | I |

you |

he |

she |

it |

we |

they |

[total] |

| the best __ can | 1,830,000 | 1,700,000 | 280,000 | 93,100 | 795,000 | 1,660,000 | 1,280,000 | |

| the best that __ can | 225,000 | 175,000 | 28,600 | 12,600 | 75,100 | 161,000 | 126,000 | |

| best/best as ratio | 8.1 | 9.7 | 9.8 | 7.3 | 10.6 | 10.3 | 10.2 | 9.5 |

Again, the (proportional) counts are generally pretty consistent across the search engines:

But again, there's something funny going on with "she", though this time it only shows up in Yahoo's counts:

I remain puzzled about what is really behind this -- maybe something about the typical language of porn site link nests? My interest in reverse engineering search engines is not great enough to motivate me to spend much more time investigating it. But if you know, or have a good guess, tell me and I'll tell the world.

Does sisomo have sisomomentum?

Sometimes it's easy to spot neologisms that are bound to fail. But there can be a multitude of reasons why a freshly minted word or phrase turns out to be a nonstarter. As noted here previously, Allan Metcalf discerned five factors necessary for a neologism to catch fire, acronymized as FUDGE: Frequency of use, Unobtrusiveness, Diversity of users and situations, Generation of other forms and meanings, and Endurance of the concept. To these five we might add a sixth criterion: Resistance to public backlash. Of course, that's mainly a concern for coinages that are foisted on the public for possibly cynical marketing purposes. One recent example was Cyber Monday, specifically designed to boost post-Thanksgiving online purchases. Now comes the latest self-conscious creation from the world of advertising: sisomo.

Sometimes it's easy to spot neologisms that are bound to fail. But there can be a multitude of reasons why a freshly minted word or phrase turns out to be a nonstarter. As noted here previously, Allan Metcalf discerned five factors necessary for a neologism to catch fire, acronymized as FUDGE: Frequency of use, Unobtrusiveness, Diversity of users and situations, Generation of other forms and meanings, and Endurance of the concept. To these five we might add a sixth criterion: Resistance to public backlash. Of course, that's mainly a concern for coinages that are foisted on the public for possibly cynical marketing purposes. One recent example was Cyber Monday, specifically designed to boost post-Thanksgiving online purchases. Now comes the latest self-conscious creation from the world of advertising: sisomo.

No, it's not some new variant of sudoku (or suduko, or sudoko, or soduko, or...). It's the brainchild of Kevin Roberts, CEO of the advertising giant Saatchi & Saatchi, and it's an acronymic blend of "sight, sound, and motion," trumpeted as "a new word for a new world." The website that Roberts created to popularize the word supplies the pronunciation upon loading, whether you want to hear it or not: it's /sɪsoʊmoʊ/, with roughly even syllabic stress (though that stress pattern is likely due to the synthesized voices that contribute to the site's earnestly techno-futuristic flourishes).

Strike one against sisomo: it's a graphemic blend rather than a phonemic one, taking the first two letters of each of the component words regardless of the resulting mismatch between sound and spelling. (Perhaps they test-marketed the fully diphthongized sighsoumo and it didn't fly.) Graphemic blends do occasionally crop up in English, particularly those of the acronymic type that take the first letter or two from words in a phrase, such as sonar from "sound navigation ranging," or COBOL from "COmmon Business-Oriented Language." But extracting the first two letters from each word in a series is not a productive source of English neologizing. (You never know, though — sisomo could be thought to have a particularly "modern" sound, as sonar and COBOL were no doubt considered at the time of their coinage.)

The word was introduced at last month's Ad:Tech conference in New York, where Roberts unveiled it as his label for a purportedly new advertising imperative: the need to combine sight, sound, and motion in an emotionally captivating package, now typically mediated by multiple video screens (TVs, cellphones, computers, etc.). Unsurprisingly, he also announced that his buzzword is the topic of a new book he was plugging, Sisomo: The Future on Screen.

Roberts further explained his push for the new word in an article in the Dec. 29 New Zealand Herald:

"Revolution starts with language," he said - quoting publisher Alan Webber. "So, creating a new word was a deliberate move."

It's technically a noun, but Roberts has no shortage of ideas for how it can be dropped into casual conversation as a verb. How about: "We're sisomoing all our ideas" ... or "The story sisomoed up really well."

I think Roberts might be jumping the gun in his pursuit of one of Metcalf's five factors, "generation of other forms and meanings." He's not only imagining a transition from noun to verb but also to an idiomatic phrasal verb, sisomo up. (And not just a phrasal verb but an intransitive one. Even particularly successful neologisms like google usually stay transitive when making the phrasal-verb leap, though there are scattered examples of people talking about the things that google up when they're a-googlin'.)

Roberts is also fond of blending upon his blend: the text of his Ad:Tech speech reveals sisomovers, sisomojo, and sisomotivators. One blogger at the conference, who also mentioned Roberts' use of sisomoments and sisomovies, thought that this made it a "fun" word; others might find these strained attempts at whimsy to be mildly annoying. And again, isn't this jumping the gun just a bit? Has Roberts forgotten the cautionary tale of 2004 presidential candidate Joe Lieberman and his self-defeating proclamation of Joementum?

A cardinal rule of neologizing is that one person can't carry the load of hyping the coinage, even a master hyper (a hyper-hyper, if you will) like Roberts. Others may be building on the blend, however. Another blogger from the world of advertising has suggested the further acronymic elaborations of misisomo (marketer-inspired sight sound and motion) and cisisomo (consumer-inspired sight sound and motion).

Obviously, Roberts is going to need recognition beyond advertising circles if he hopes to achieve neologistic nirvana with sisomo. In the New Zealand Herald article, he claims that the buzz is building:

Roberts said a lot of the interest in the concept was coming from the news media, the big retailers and the electronics companies. ...

Roberts launched the word sisomo at an advertising industry conference in New York last month.

Since then he has made two US TV appearances and attracted many articles in business sections. One internet-based English dictionary has sisomo on its list of candidates for inclusion. But Roberts is hoping for more of a global linguistic splash.

"I've just been in Russia and Korea talking about it and they can all say sisomo," he said. "We just want to see it becoming part of the lexicon."

I'm pretty certain that the "internet-based English dictionary" mentioned in the article is none other than Grant Barrett's Double-Tongued Word Wrester, a favorite at Language Log Plaza. DTWW was on the case almost immediately, with a citation posted Nov. 9. (The citation was from a live-blogger at the Ad:Tech conference, whose mention that Roberts "coined a word" must have set off bells at DTWW's blog-tracking facilities.)

I'm not so sure that inclusion in the DTWW citation queue is really an indication of the incipient popularization of sisomo. After all, the queue has room for such marginal coinages as hideawfulous and charmesty. But Roberts might be on to something with his realization that sisomo presents no pronunciation problems for Russians or Koreans. Even if sisomo proves to be a dud stateside, it could be the neologistic equivalent of movies like Kingdom of Heaven: disappointing domestically, but an impressive performer overseas.

[Update: More on the history of such orthographic blends in this post.]

December 27, 2005

The brave new world of computational neurolinguistics

Yesterday I wrote about an ITV documentary, airing today, that promises to unveil some weird-sounding "neurolinguistic" research on the endorphin-stimulating effects of Agatha Christie's prose style. I asked British readers for more information, and even before seeing the program, Ray Girvan was able to help:

Being commissioned for a ITV documentary marking the 75h anniversary of the creation of Miss Marple, the exercise has "promotional" written all over it. ITV has an ongoing coproduction agreement with Chorion plc, rights owners and makers of Agatha Christie TV films.

The premise of the enduring popularity of Christie's text doesn't entirely bear scrutiny. Sales of her books were declining in the late 1990s, and have only risen again after extensive rebranding and promotion by Chorion plc, who bought the rights in 1999.

Now why didn't the Times, the Guardian, the BBC and the rest of the British mainstream media give us this sensible account of the commercial forces behind the Agatha "research"?

Take a look at the breathless BBC story headlined "Scientists study Christie success". Its subhead was "Novelist Agatha Christie used words that invoked a chemical response in readers and made her books 'literally unputdownable', scientists have said." The lead sentence was "A neurolinguistic study of more than 80 of her novels concluded that her phrases triggered a pleasure response".

The BBC article gives us no hint that ITV has a financial interest in the "enduring popularity" of Christie's work. The article is in the entertainment section, not the science section or the business section; but a majority of readers will surely see it as a story about the popularization of scientific research, not a story about a public relations stunt in support of a commercial partnership. (There may well be some real science behind the program -- I'll reserve judgment on that until the work is described somewhere in enough detail to evaluate.)

Well, I've made a New Year's resolution to look on the bright side, so I'm going stop berating science journalism at the BBC-- clearly a lost cause -- and focus instead on the wonderful new opportunity here for enterprising teams of computational and neurological linguists.

The recipe is simple. Take one fading literary property with a cash-rich proprietor, one statistical string analysis algorithm, and a sheaf of brain images with hot and cool color patches. Mix well. Sprinkle with neurotransmitters; add sex and violence to taste; and serve on a bed of fresh press releases.

A few years in the future, I look forward to reading the first of a veritable river of publications from the Doubleday Institute of Computational Neurolinguistics at UCSC: Pullum, G. et al., "The obsessive-compulsive code: effects of anarthrous noun phrases on striatal dopamine D2 receptors".

[I should stress that the neuroscience of language is an eminently respectable field, where rigorous and exciting work is being done; and that integration of advanced computational techniques into this field is one of its most promising areas. In this post, I'm poking fun at a case where press reports suggest that the field is being exploited for publicity purposes by a partnership of media companies.]

[Update: Ray Girvan emailed:

I watched the programme, and updated my weblog entry with the notes I made. I admit I'm biased - I think Agatha Christie's work is execrable - but the programme was nevertheless very poor science.

They did various computer analyses of word and phrase distribution: pretty standard computational linguistics stuff. The shaky part was the interpretation of the results by various non-mainstream pundits - a Lacanian psychoanalyst, a stage hypnotist, and two Neuro-linguistic Programming experts - who all asserted that the observed word distributions literally hypnotised the reader.

In his weblog entry, Ray Girvan describes the program at greater length:

The main experts were computational linguist Dr Pernilla Danielsson (billed as "academic champion of communications") and Dr Markus Dahl, a research fellow (a Johnny Depp lookalike, including top hat) at the University of London Institute of English Studies. The camera tracked around them portentously as they sat at glowing laptops in a dimly-lit smoky room and, bit by bit, revealed the purported secret of Christie's success. As LL guessed, Dr Roland Kapferer wasn't among them; he was revealed in the credits as the associate producer/writer for the programme.

The science boiled down to a) computerised textual analysis - word frequencies, and so on - and b) subjective psychological interpretation of the results thereof. Christie's nearly invariable use of "said", rather than said-bookisms, was claimed to enable readers to concentrate on the plot. Her works' narrow range on a 3D scatter plot (axes and variables unknown) indicated a consistent style, assumed to be a Good Thing compared to Arthur Conan Doyle. Sudden coherent sections in her otherwise messy notebook indicated her getting "into the flow" - a trancelike writing state (Darian Leader, a psychoanalyst, endorsed the idea that she had been in a similar, deeper trance during her famous 10-day disappearance) and Dr Dahl argued that this trance transferred to the reader.

The trance theory was the central thrust of the programme. David Shephard, a Master Trainer in Neurolinguistic Programming, asserted that the level of repetition of key concepts over small spaces (e.g "life", "living", "live", "death" in a couple of paragraphs) consolidated concepts in the reader's mind. He claimed further that we can only hold nine concepts in the mind at once (I assume a reference to Miller's classic Seven plus or minus two figure for short-term memory capacity) and that Christie's use of more than nine characters overloads the reader's conscious mind, making them literally go into a trance. Dr Dahl cited a further textual result - Christie's "ingenious device" of controlling the reading speed by decreasing the level of detail toward the ends of books, and stage hypnotist Paul McKenna claimed that this invoked the neurotransmitters of craving and release, making the books addictive.

Finally they rolled out the big gun, Dr Richard Bandler, "father of Neurolinguistic Programming", who repeated the assertion of Christie literally hypnotising readers, and said the lack of detail helped maintain that trance. And that was it: "extensive computer analysis", concluded the Joanna Lumley voiceover, has enabled a "quantum leap" in understanding the source of Christie's enduring popularity. Why, surely only a cynic could remain unconvinced by such rigorous science...

I expect we Americans will be able to see this on the Discovery Channel or the History Channel before long. If so, my New Year's Resolution to focus on the positive side of linguistics in the media will be subjected to a rigorous test. ]

December 26, 2005

Kenzi, Camerair, and other hybrid beasts

The recent outbreak of blends combining famous names — from Brangelina to Scalito — was notable enough to merit inclusion in the New York Times' annual roundup of buzzwords. Though it seems that the faddish blending of celebrity couples is finally on the wane, political portmanteaus continue to emerge on a regular basis. Such name-blends are sometimes coined to underscore the similarity of two politicians, especially if they belong to opposing parties and should ostensibly be on different sides of the ideological fence. In his Dec. 24 column, conservative pundit Robert Novak mentions one recent example:

Republican senators complain that Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, liberal lion of the Senate, has taken over effective control of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee because the Republican chairman, Sen. Michael Enzi of Wyoming, defers to him so much. In an era of intense partisanship, Kennedy and Enzi collaborate on spending and regulatory measures before their committee. ... Behind his back, Republican staffers have come to refer to the chairman as Sen. "Kenzi."

Unseemly bipartisanship is apparently enough to trigger a disparaging name-blend in the current Congress (particularly if there is a felicitous intersection of phonetic material, as with /'kɛnədi/ and /'ɛnzi/). Across the Atlantic, Conservative and Labour party faithful similarly express their wariness of bland centrism through onomastic fusions. In the Guardian, Timothy Ash suggests a blend to highlight the shared banality of Tory leader David Cameron and the man he hopes to replace as prime minister, Labour's Tony Blair: Camerair. Ash notes that Nick Cohen of the New Statesman has already beaten him to the punch with a different blend: Blameron. But Ash says he prefers his version since it "hints at the essential mixture of television cameras and hot air." (I'd say that Camerair is also preferable for its cheesy connotations, as it's reminiscent of Camembert.)

Camerair and Blameron have a clear progenitor in British political parlance. When Rab Butler, a Tory, replaced the Labour Party's Hugh Gaitskell as Chancellor of the Exchequer in the 1950s, the Economist satirized Butler's similarities to his predecessor by imagining a hybrid of the two chancellors named "Mr. Butskell." Conservative-Labour consensus politics then came to be labeled Butskellism.

Though there isn't such a high-profile precursor in U.S. political name-blending, it's not a particularly new phenomenon in this country either. In the April 1934 issue of American Speech, Robert Withington noted a name-blend in a book that had been published the previous year, William Aylott Orton's America in Search of Culture. Orton makes reference to "the Hoolidge era," conflating the presidential terms of Hoover and his predecessor Coolidge. Unlike Kenzi, Camerair, or Butskell, the Hoolidge blend combines members of the same party, suggesting the homogeneity of two successive Republican administrations rather than bipartisan blandness. (Withington also discerns in Hoolidge echoes of hooligan, evoking "a certain ridicule for the chicken-in-the-pot era which stressed material prosperity." This connotation would be missing if Orton had coined a chronologically ordered blend like Coover or Coolver.) There are no doubt earlier name-blends to be found in American political history — after all, one of the most famous political coinages is a blend of man and beast, dating to 1812: Gerrymander, combining Gerry (i.e., Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry) with salamander.

Name-blending also has a durable lineage in literary criticism. In 1888, an article in the Saturday Review belittled the illustrious crank Ignatius Donnelly and his newly published book The Great Cryptogram, which supposedly uncovered the hidden ciphers proving that Shakespeare's plays were written by Sir Francis Bacon. The article, entitled "Ignatius Shacon," took great delight in satirizing Donnelly and his followers, the Shaconians (and their supposed foes, the Bakespearians). Shaconian hasn't had much staying power (except among curators of obscure words, variously deemed grandiloquent, luciferous, or simply worthless). A more famous literary name-blend appeared in a 1908 essay by George Bernard Shaw, in which Shaw conceived of a mythical four-legged creature combining aspects of his colleagues G.K. Chesterton and Hillaire Belloc. He called it the Chesterbelloc. I wonder what Shaw would have made of our current menagerie of Bennifers, Tomkats, and Vaughnistons?

(And speaking of blends, merry Chrismukkah, or Chrismahanukwanzakah if you prefer.)

The Udmurtian code: saving Finno-Ugric in Russia

The Finno-Ugric family of languages contains Finnish, and its close relative Estonian, and Sami (the language of the Lappish people of the far north), and various related languages languages in Russia (Komi, Mari, Udmurt), along with a distant southern relative, Hungarian. It's actually not that easy to show with clear etymologies and sound changes that Finnish and Hungarian really are cousins. There are maybe 200 solid cognates. (A cognate is a word showing in both its pronunciation and its meaning or grammatical properties that it was ancestrally shared by the relevant languages, and was transmitted in altered phonological form down the centuries rather than being directly borrowed between modern languages.) The Economist (December 24th, page 73) has a very interesting article about the way Finno-Ugric languages are dying in Russia. In connection with the discussion of linguistic relatedness, it cites Estonian philologist Mall Hellam as having come up with a sentence that should be intelligible to Finnish, Estonian, and Hungarian speakers alike:

| Finnish: | Elävä kala ui veden alla. |

| Estonian: | Elav kala ujub vee all. |

| Hungarian: | Eleven hal úszkál a víz alatt. |

The translation is "The living fish swims in water." Looking at the examples (which are in the standard spellings for the three languages) set me to wondering if there is indeed mutual intelligibility here, as opposed to just full cognate status for all words. It seems rather implausible to me that a monolingual Hungarian would be able to understand even one sentence of Finnish unless they took it on as a puzzle-solving exercise. I guess I know how to find out: I can pronounce Finnish well enough, and I have Hungarian friends who don't read Language Log. I'll do some work on the question.

[In fact I have already heard from a Finn living in Hungary, Vili Manula, who says no Hungarians understand the Finnish sentence, and certainly no Finn would understand the Hungarian one. So the experiments are done, and my suspicions are justified. And a thread on the discussion forum sci.lang pretty much demolishes the mutual intelligibility claims; it seems the sentences have a long history in the Finno-Ugric world, and calling them mutually intelligible was always way, way exaggerated.]

Talking of things being far-fetched, one member of the Finno-Ugric movement headquartered in Talinn (Estonia), fearing that publishing things like a slim volume of poetry in Mari was not going to be enough to ensure the survival of Finno-Ugric in the Russian area, remarked to The Economist's reporter that what they really need is The Da Vinci Code in Udmurt. Which set me to wondering whether you would need to translate it into bad Udmurt to get the feel of the original.

The Agatha Christie Code: Stylometry, serotonin and the oscillation overthruster

Agatha Christie, who died in 1976, has been in the news a lot lately. Atai Winkler's "research" for lulu.com on the statistics of book titles, discussed on Language Log a couple of weeks ago, gave rise to some of the headlines, for example "Computer Model Names Agatha Christie's 'Sleeping Murder' as 'The Perfect Title' for a Best-Seller". But others reference a different piece of techno-literary sleuthing. Richard Brooks of the Sunday Times tells us, in "Agatha Christie's grey cells mystery", that "leading universities" have discovered that Christie's appeal is due to "the chemical messengers in the brain that induce pleasure and satisfaction":

The mystery behind Agatha Christie’s enduring popularity may have been solved by three leading universities collaborating on a study of more than 80 of her crime novels.

Despite her worldwide sales of two billion, critics such as the crime writer P D James pan her writing style and “cardboard cut-out” characters. But the study by neuro-linguists at the universities of London, Birmingham and Warwick shows that she peppered her prose with phrases that act as a trigger to raise levels of serotonin and endorphins, the chemical messengers in the brain that induce pleasure and satisfaction.

Some might think that this is a complicated way of saying that people like the way she writes, but I'll reserve judgment until I see how the researchers themselves put it.

Meanwhile, Russell Jackson in The Scotsman takes a different tack in "Experts solve mystery of Agatha Christie's success". Apparently "linguistics experts" have discovered that the secret is a mathematical formula:

The study was carried out by linguistics experts at Warwick, Birmingham and London universities and the results are to be revealed in an ITV1 documentary on 27 December.

Dr Roland Kapferer, the project's leader, said: "It is extraordinary just how timeless and popular Agatha Christie's books remain. These initial findings indicate that there is a mathematical formula that accounts for her success."

Again, this seems to be a complicated way of saying that Christie's success is due to identifiable properties of her writing, rather than a special intervention of divine providence in the marketplace. I haven't read the rest of the news reports, but no doubt other journalists have explained that Ms. Christie's enduring success has been shown to be an emergent property of the arrangements of atoms and molecules in the printed copies of her works.

This 12/19/2005 news release from the University of Birmingham explains more about the formulae involved: this part is apparently work by Pernilla Danielsson, a computational linguist in the Department of English:

Agatha Christie used a limited vocabulary, repetition, short sentences and a large amount of dialogue in her text according to research carried out by the University of Birmingham for ITV 1’s special Christmas programme about the author.

Dr Pernilla Danielsson from the University’s Department of English has analysed the type of words that Christie used in her detective novels to develop a better understanding of her writing style and to find out why she is the world’s best selling author. To do this she has also compared Christie’s writing to that of Arthur Conan Doyle, author of Hound of the Baskervilles.

This sounds like a plausible project in stylometry, but there's nothing about it yet in any of Dr. Danielsson's works that Google or Google Scholar can find. And the Birmingham press release doesn't mention anything about serotonin or endorphins.

I couldn't find anything about this project on the University of Warwick's web site, or various of the University of London's sites. A search for "Agatha Project" on Google Scholar and other indices of scientific and technical publications turned up only some references to a completely different "Agatha Project", an old HP expert system for diagnosing PA-RISC processor board failures.

And I couldn't find anything anywhere about Dr. Roland Kapferer, "the project's leader", unless he's the Roland Kapferer referenced here as a "film and television producer and freelance writer based in London and Sydney", with "a PhD in Philosophy from the University of Macquarie", who may also be the same as the Roland Kapferer who is the lead singer for Professor Groove and the Booty Affair. If so, then he's a sort of real-world Buckaroo Banzai: could the rest of the Hong Kong Cavaliers be somewhere in the background, measuring those serotonin levels?

The ITV1 program " The Agatha Christie Code" is being "revealed" tomorrow at 16:00, so perhaps some British readers will be able to provide additional information about this research. Who, for example, is responsible for the "neuro" aspect? How did they measure serotonin and endorphins, or is that all journalistic free association? Is there going to be a publication at some point, or was this research done exclusively for the ITV Special? And has anyone seen Penny Priddy?

So far, the "Agatha Project" shares a crucial negative feature with the Lulu Titlescorer and last fall's "infomania study": there's no publication or documentation. No equations, no published data, no fitted models, no source code. Just press releases and (in the case of Agatha) a TV program. Until what they did is documented in enough detail for others to evaluate, the press reports are the same category as Professor Hikita's Oscillation Overthruster: evocative fiction. Looking on the bright side, I guess it's nice to see some popular evocative fiction with a linguistic theme.

[Update: the BBC, vying with The Sunday Timies in earnest credulity, provides some juicy details apparently supplied by Dr. Kapferer -- a few of the specific "language patterns" which "stimulated higher than usual activity in the brain" and "triggered a pleasure response".

The team found that common phrases used by Christie acted as a trigger to raise levels of serotonin and endorphins, the chemical messengers in the brain that induce pleasure and satisfaction.

These phrases included "can you keep an eye on this", "more or less", "a day or two" and "something like that".

"The release of these neurological opiates makes Christie's writing literally unputdownable," Dr Kapferer said.

If it weren't so obviously unethical -- and also so obviously ineffective -- I'd suggest a small experiment at your local watering hole:

| You: | Can you keep an eye on this while I visit the restroom? |

| Attractive potential new friend: | Um, OK. |

| You: | You seem trustworthy, more or less. |

| A.P.N.F.: | [uneasily] Uh huh... |

| You: | I won't be gone more than a day or two. |

| A.P.N.F.: | Visiting the restroom. |

| You: | Something like that. |

Intoxicated by potent neurological opiates, your new friend will be thenceforth be addicted to your company. Really, the BBC says so. ]

[Update: more on this here.]

December 25, 2005

Not a brilliantological invention

Gene Shalit's opinion of the new King Kong is that it is "so gargantuan that I must create new words to describe it: fabularious... a brilliantological humongousness of marvelosity". There's that funny layperson's fetishizing of words again: why do people think that to say something impressive you need new words? What you need is skill in deploying the ones we already have. You should at least have a crack at explaining your view before giving up and alleging inadequacy in the English word stock.

But enough curmudgeonliness, let's just do some empirical work. Did Gene's amateur efforts in lexical morphology actually result in any new words? It turns out that inventing words for a language as well stocked as English is not quite as easy as you might think.

First, fabularious is not original; it was invented (not necessarily for the first time) by a blogger named Sam in an affectionate comment addressed to a blogger named Julia on February 11, 2004 ("You are hilarious and fabulous, so much so that I am combining it into a single word--Fabularious. Use it, love it"). Second, marvelosity is not new either: it gets 377 Google hits. Third, humongousness certainly isn't new; the jocular adjective it is regularly derived from, humongous, gets about 2.37 million hits, so I was surprised to find that humongousness got only 471; but that's still enough to quash the claim of inventing new words.

So Gene is down to just one out of four. And brilliantological isn't exactly brilliant, is it? Just about every native speaker knows that for any morpheme X of the appropriate sort, the appropriate sort being either a noun or what The Cambridge Grammar calls a combining form (like geo- or morpho-), Xological means having to do with or belonging to Xology, and Xology is the academic study of whatever the root X denotes (e.g., the earth if X = geo). So ‘King Kong’ has something to do with the academic study of... brilliant?

As we have definitely remarked before here on Language Log, sometimes you just absolutely know that a word is not going to catch on, don't you?

December 24, 2005

"60 Minutes" doomed to repeat itself

About halfway through the fourth quarter of the NFL matchup between the Indianapolis Colts and the Seattle Seahawks, one of the announcers for the CBS telecast delivered the standard rat-a-tat promo for upcoming shows on the network:

Tomorrow on "60 Minutes"... A year after the tsunami. In a culture that has no concept of time, how did one group of people know ahead of time that it was coming?

Yes, it's the return of the Moken, the "sea gypsies" living on islands in the Andaman Sea that a "60 Minutes" crew visited in the wake of the tsunami. Back in March, Bob Simon informed us (extrapolating wildly from sketchy comments by anthropologist Jacques Ivanoff) that because the Moken language doesn't display the temporal markers that Western languages do, the islanders therefore have "no notion of time."

Now here we are again a year after the tsunami, and the show is still peddling the same "Whorf Lite" nonsense. It almost makes you wonder — despite the tick-tick-tick of Western modernity emblematized by the "60 Minutes" stopwatch, perhaps it's American TV journalists who live in an unchanging, ahistorical present tense, not those "primitive" islanders.

L(a)ying snow

Some of the more antisocial neighbours near where we live did not bother to bestir themselves with a snow shovel the way we did after the big early snowfall that hit the Boston area on December 9. Their laziness, plus some partial meltings and re-freezings, has turned parts of the sidewalks between our Inman Square apartment and the Harvard/Radcliffe area into a treacherous glacier. The walk to the Radcliffe Institute that Barbara and I have to do each morning has become difficult and dangerous. We were surprised to learn from our friend Tom Lehrer at lunch yesterday that snow laziness is a famous cultural feature of Cambridge quite specifically. David T. W. McCord (Harvard class of ’21) used to write a column in the Harvard Alumni Bulletin called "The College Pump", and sometimes he would add in little verses to make columns fit. The verse he published on March 15, 1940, went like this:

In Boston when it snows at night

They clean it up by candle-light;

In Cambridge, quite the other way,

It snows and there they leave it lay.

But of course, that's one of the instances of lay that should have been lie, isn't it?

You knew that. You remember it from my advice column on the topic, which you understood in full and were not the slightest bit confused by. When Boston's weather spirits decide to lay down some snow and people leave it alone, they let it lie. (The construction leave it lie is unusual in modern Standard English; let it lie or leave it there are standard, but leave it lie is not.)

The snow lay there, crushed and frozen and slippery, until today's thaw, in fact. That occurrence of lay is OK, it's a preterite. Like the one in this Christmas carol:

Good King Wenceslas looked out

On the feast of Stephen

When the snow lay all about

Deep and crisp and even

There it's lay not lie because although it's intransitive the verb looked tells you we're in the past so you get the preterite of intransitive lie which looks exactly like the present of transitive lay (whereas the preterite of lay doesn't look like either lay or lie). Would I lie to you?

Merry Christmas!

December 23, 2005

Multiplying ideologies considered harmful

Tim Groseclose and Jeff Milyo's recently-published paper ( ("A Measure of Media Bias", The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Volume 120, Number 4, November 2005, pp. 1191-1237) has evoked plenty of cheers and jeers around the web. The complaints that I've read so far (e.g. from Brendan Nyhan, Dow Jones, Media Matters) have mainly focused on alleged flaws in the data or oddities in the conclusions. I'm more interested in the structure of their model, as I explained yesterday.

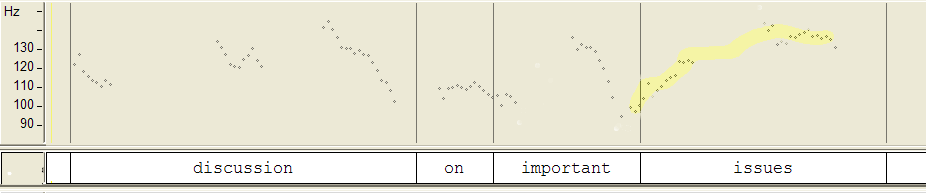

As presented in the published paper, G&M's model predicts that perfectly conservative legislators -- those with ADA ratings of 0% -- are equally likely to cite left-wing and right-wing sources, basing their choices only on ideology-free "valence" qualities such as authoritativeness or accessibility. By contrast, perfectly liberal legislators are predicted to take both ideology and valence into account, preferring to cite left-wing sources as well as higher-quality or more accessible ones. Exactly the same pattern is predicted for media outlets, where the conversative ones should be indifferent to ideology, while the more liberal the media, the more strongly ideological the predicted motivation.

Common sense offers no reason to think that either politicians or journalists should behave like this, and everyday experience suggest that they don't -- the role of ideology in choice of sources, whatever it is, doesn't seem to be qualitatively different in this way across the political spectrum. Certainly Groseclose and Milyo don't offer any evidence to support such a theory.

This curious implication is a consequence of two things: first, G&M represent political opinion in terms of ADA scores, which vary from 0 (most conservative) to 100 (most liberal); and second, they put political opinion into their equations in the form of the multiplicative terms xibj (where xi is "the average adjusted ADA score of the ith member of Congress" and bj "indicates the ideology of the [jth] think tank") and cmbj, where cm is "the estimated adjusted ADA score of the mth media outlet" and bj is again the bias of the jth think tank.

As I pointed out yesterday, the odd idea that conservatives don't care about ideology can be removed by quantifying political opinion as a variable that is symmetrical around zero, say from -1 to 1. (It's possible that G&M actually did this internal to their model-fitting, though I can't find any discussion in their paper to that effect.) However, this leaves us with two other curious consequences of the choice to multiply ideologies.

First, on a quantitatively symmetrical political spectrum it's the centrists -- those with a political position quantified as 0 -- who don't care about ideology, and are just as happy to quote a far-right or far-left source as a centrist source. This also seems wrong to me. Common sense suggests that centrists ought to be just as prone as right-wingers and left-wingers to quote sources whose political positions are similar to their own.

A second odd implication of multiplying ideologies is that as soon as you move off of the political zero, your favorite position -- the one you derive the most utility from citing -- become the most extreme opinion on your side of the fence, i.e. with the same sign. If zero is the center of the political spectrum, and I'm a centrist just a bit to the right of center, then I'll maximize my "utility" by quoting the most rabid right-wing sources I can find. If I happen to drift just a bit to the left of center, then suddenly I'm happiest to quote the wildest left-wing sources. This again seems preposterous as a psycho-political theory.

I'm on record (and even with a bit of evidence) as being skeptical of the view that the relationship between ideology and citational preferences is a simple one. And I'll also emphasize here my skepticism that political opinions are well modeled by a single dimension. But whatever the empirical relationship between political views and citational practices is, it seems unlikely that ideological multiplication captures it accurately.

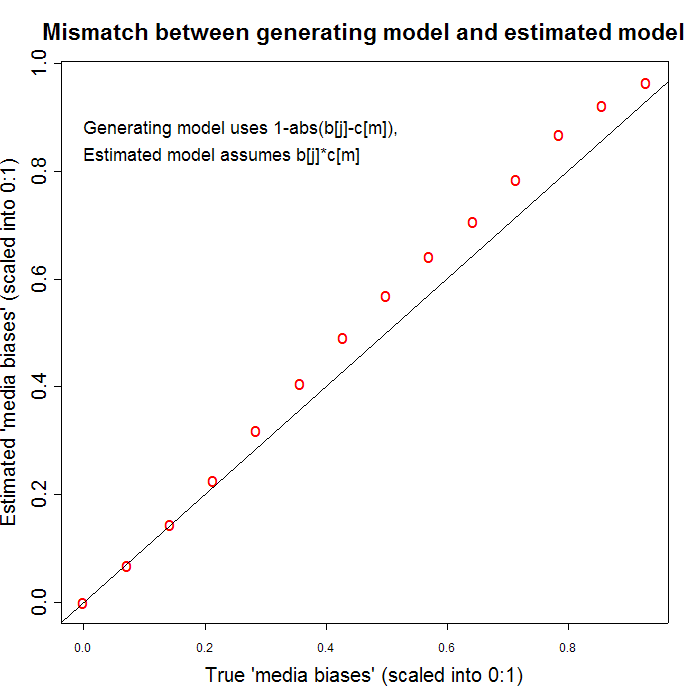

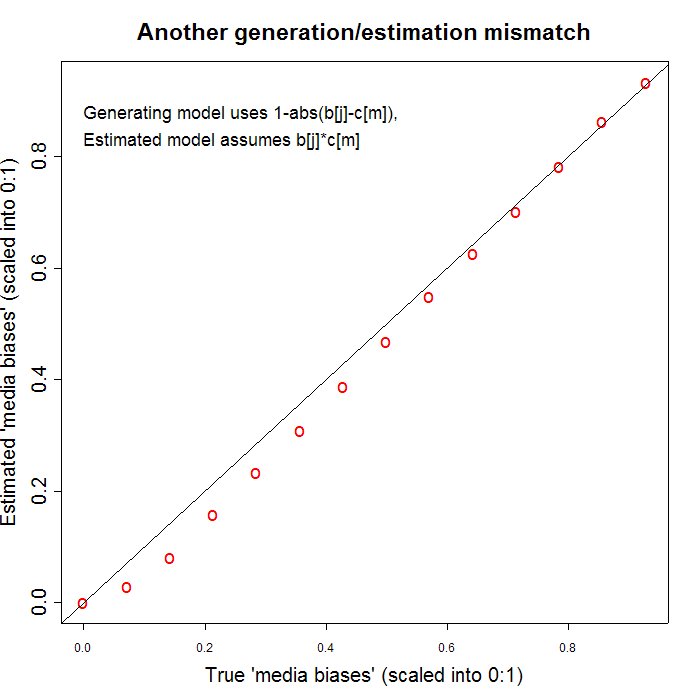

On the other hand, does any of this matter? It's certainly going to do some odd things to the fitted parameters of G&M's model. For example, if they really treated the conservative position as the zero point of the political spectrum, then I'm pretty sure that their estimated "valence" parameters (which they don't publish) will have encoded quite a bit of ideological information. If we had access to G&M's data -- it would be nice if they posted it somewhere -- we could explore various hypothesis about the consequences of trying models with different forms. Since (as far as I know) the data isn't available, an alternative is to look at what happens in artificial cases. That is, we can generate some artificial data with one model, and look to see what the consequences are of fitting a different sort of model to it.

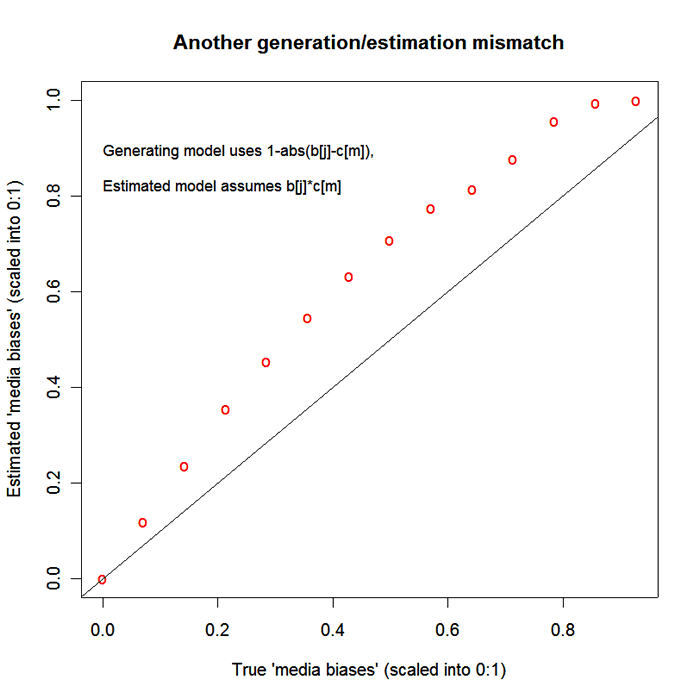

I had a spare hour this afternoon, so I tried a simple example of this. I generated data with a model in which people most like to quote sources whose political stance is closest to their own -- left, right or center -- and then fitted a model of the form that G&M propose. The R script that I wrote to do this, with some comments, is here, if you want to see the details. (I banged this out rather quickly, so please let me know if you see any mistakes.) One consequence of this generation/fitting mismatch seems to be that the "valence" factor for the think tanks (which I assigned randomly) and the noise in the citation counts perturb the "ideology" and "bias" estimates in a way that looks rather non-random. I've illustrated this with two graphs showing the difference between the "true" underlying media bias parameters (with which I generated the data) and the estimated media bias parameters given G&M's model. The first graph shows a run in which nearly all the media biases are overestimated,

while the other shows a run in which nearly all the media biases are underestimated.

The only difference was different seeds for the random number generator. I used rather small amount of noise in the citation counts -- noisier counts give bigger deviations from the true parameter values, like this one:

Presumably similar effects could be caused by real-word "valence" variation or by real-world citation noise. Nearly all runs that I tried showed this kind of systematic and gradual bending of the estimates relative to the real settings, rather than the sort of erratic divergences that you might expect to be the consequences of noise. Since R is free software, you can use my script yourself as a basis for checking what I did and for exploring related issues.

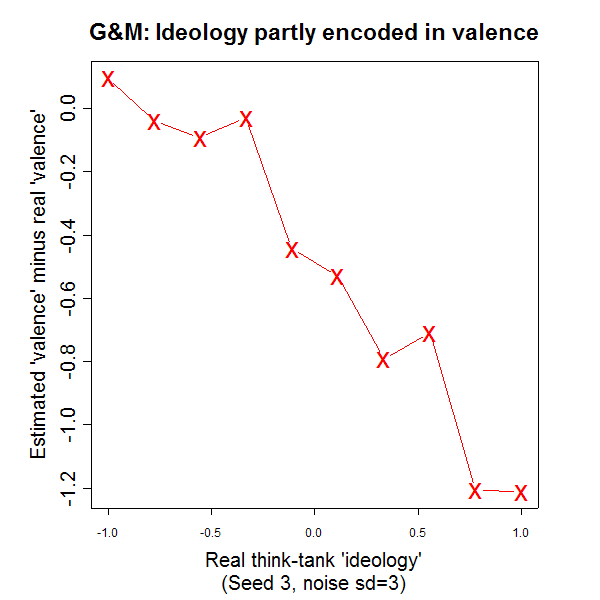

(By the way, the mixture of underlying 'ideology' into estimated 'valence' can be seen clearly in this modeling exercise -- here's a plot illustrating this:

)

I'm not claiming to have shown that G&M's finding of quantitative media bias is an artefact. I do assert, though, that multiplying ideologies to get citation utilities (and through them, citation probabilities) is a choice that makes very implausible psychological claims, for which no evidence is presented. And fitting ideology-multiplying models to data generated by processes with very different properties can definitely create systematic artefacts of a non-obvious sort.

No regular readers of Language Log will suspect me of being a reflexive defender of the mass media. I accept that news reporting is biased in all sorts of ways, along with (in my opinion) more serious flaws of focus and quality. I think that it's a very interesting idea to try to start from congressional voting patterns and congressional citation patterns, in order to infer a political stance for journalism by reference to journalistic citation patterns. I also think that many if not most of the complaints directed against G&M are motivated in part by ideological disagreement -- just as much of the praise for their work is motivated by ideological agreement. It would be nice if there were a less politically fraught body of data on which such modeling exercises could be explored.

December 22, 2005

Linguistics, politics, mathematics

In the end, this post is about the recently-published study of media bias by Tim Groseclose and Jeff Milyo ("A Measure of Media Bias", The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Volume 120, Number 4, November 2005, pp. 1191-1237). Earlier versions of that study have been widely reported and discussed over the past year and a half, including here on Language Log, with a critique by Geoff Nunberg, a response by Groseclose and Milyo, and a few other comments (here, here, and here). I started to play around with their model on the computer, and at the first step, something about the structure of the model took me aback. But before I get to the point, let me set the stage.

Last week, Penn's president had a holiday party for the faculty, in a big tent behind her house. In the midst of the throng I was talking with Elihu Katz and some other people from the Annenberg School for Communication, when another colleague, on being introduced, asked how we happened to be acquainted. Interpreting this as a question about academic disciplines rather than personal histories -- what could a sociologist have in common with a linguist? -- someone said something about a shared interest in communication. Elihu, who knows a thing or two about social networks, waved his hand at the crowd and said "well, I bet that 60% of the people here work on something connected to communication".

In fact, there's a cultural gulf between people who study large-scale communication -- media, politics, advertising -- and people who study small-scale communication -- individual speakers and hearers. This is one of the many boundary lines in the intellectual Balkans of research on language, meaning and communicative interaction, but I've felt for a long time that it's one of the borders where freer trade is most needed.

Some of us at Penn have recently gotten an NSF IGERT ("Interdisciplinary Graduate Education and Research Training") grant on the theme of "Language and Communication Sciences". Starting in January, I'm co-teaching a "Mathematical Foundations" course for this program, aimed introducing graduate students to a wide range of mathematical topics that are relevant to animal, human or machine communication. So I thought I'd take a small step in the direction of intellectual free trade by importing a problem or two from relevant areas of economics, political science or sociology.