May 31, 2004

Construal in Houston

According to the Houston Chronicle, "an 18-wheeler carrying 30,000 pounds of eggs overturned" today, "[sending] an avalanche of eggs sailing over the side of the overpass, crushing a state Department of Transportation truck at a construction site below". No one was seriously hurt, but the clean-up was apparently a messy, smelly business. The supervisor, Gary Babb, explained that "we were able to save a few cases of eggs, in case you need any." But when his co-workers brought lunch to the clean-up crew, said Babb, "They brought us scrambled eggs, you believe that? Sick sense of humor, these people."

We've now reached the essential "linguistic hook" that you've no doubt been waiting for. What's the structure of "Sick sense of humor, these people"?

It's related somehow to "These people have a sick sense of humor" -- but it's not quite right to take just any sentence of the form "These PluralNouns have a SingularNounPhrase" and transform it to "SingularNounPhrase, these PluralNouns". Or is it?

I queried Google with the pattern "these * have a", and tried transforming the first half a dozen examples with a suitable structure. Mostly not too bad, the results. Sounds kind of like one of those parodies of Bush 41 that used to be popular:

These cars have a lot of problems. ?Lot of problems, these cars.

These places have a presence of their own. ?Presence of their own, these places.

These eggs have a wonderful tale to tell. ?Wonderful tale to tell, these eggs.

These zills have a beautiful tone. ?Beautiful tone, these zills.

These comics have a lot of sex in them. ?Lot of sex in them, these comics.

These scenarios have a common theme. ?Common theme, these scenarios.

You definitely need some sort of modifier or quantifier, though:

These films have a plot. *Plot, these films.

These women have a dream. *Dream, these women.

And it's apparently not great for the complement of have to get too long:

These teams have a concentrated focus on the Xbox Full Spectrum Warrior gaming front!

???Concentrated focus on the Xbox Full Spectrum Warrior gaming front, these teams!

Definite subjects with determiners other than these are similar in quality:

The Amish have a distinctive culture. ?Distinctive culture, the Amish.

Those Germans have a word for everything. ?Word for everything, those Germans.

but plural indefinite subjects seem worse:

Stroke survivors have a high risk of dementia. ??High risk of dementia, stroke survivors.

Africa's economic problems have a medical solution. *Medical solution, Africa's economic problems.

though by now all the examples are starting to sound like the slurred dialogue of stereotypical drunks. And anyhow, surely there are some more general principles at work here...

[Update: Haj Ross asks

Q: is this mebbe the same rule that does

Your cousin has been working here a long time. -> (*has) been working here a long time, your cousin.

I'm not sure about this. Even without the postposed subject, you get things like the punchline of the famous story about "Silent Cal" Coolidge returning to his home town in Vermont after the end of his presidency; going to the local story, selecting a few items, and bringing them to the cash register, without saying a word; the storekeeper ringing up the purchases, also in silence, taking payment and making change, and then closing the encounter by saying

"Been away."

to which President Coolidge responded

"Ayah."

and left the store.

Of course, you could also just comment "Sick sense of humor." without the postposed subject, if you were a stereotypically laconic New Englander instead of a stereotypically garrulous Texan.]

Word puzzle! Word puzzle!

The abbreviation for preposition is PREP; and if you replace the first and last letters by the preceding letter of the alphabet you get the name of a kind of cookie: OREO!

Can you think of another common grammatical term which yields the name of a common snack food when you replace the first and letters of its common abbreviation by the preceding letter of the alphabet, boys and girls?

No, of course you frigging can't. There isn't one. Listen, I'm going to tell you something I've never told anyone else before. I hate those stupid word puzzles that they have Will Shortz doing on National Public Radio every Sunday morning with a random listener over a bad phone line and Liane Hansen gets all nervous and giggly and sympathetic and tries to help out the listener if he turns out to be the kind of moron who is unable to achieve the marvellously useful and interesting feat of thinking up a name of a farm animal that begins with the same letter as a farm implement or something.

I suppose some people would imagine a grammarian is the sort of pointy-headed dweeb who would simply love to wake up on a Sunday morning to hear someone answer a series of questions about names of cities that sound like Latin names for ecclesiastical garments or two-word phrases for types of criminal activity where each word begins with the letter the other one ends with and then be told that since they got 3 out of 10 they will get an NPR lapel pin and a paperback college dictionary. Well those people would be dead wrong. I loathe word puzzles and when Liane Hansen introduces Will Shortz my arm twitches even if I'm asleep and my hand zaps over to the RADIO OFF button so fast that it makes a swooshing noise as it burns through the air. I couldn't give a monkey's fart about word puzzles. I couldn't...

The expressive power of human language is barely adequate to convey the profound level of apathy word puzzles provoke in me. I despise them. Actually Language Log is a bit too public a place for me to share the full visceral force of my reaction; ask me about them privately some time and I'll tell you how I really feel.

More Perfect

My grade 8 English teacher inisted on something perhaps even stupider than the obligatory omission of omissible that (that) Geoff Pullum discusses. She was of the view that one cannot combine more with an adjective like perfect that describes an absolute state. Her reasoning was that if it is correct to describe something as perfect, then the absolute has already been reached and no greater degree of perfection can be attained. This assumes a particular semantics for words like perfect, one that is plausible at first glance, but easily falsified. For instance, we can say that something is absolutely perfect, which wouldn't make sense if perfect already described the absolute state. I stand to be corrected by the semanticists, but it seems likely that when we say that something is perfect we mean that its degree of perfection falls within a distance d of absolute perfection, where the value of d is contextually determined. This allows us on the one hand to cut d down to 0 by specifying that something is absolutely perfect and on the other hand to talk about things approaching more and less closely to perfection.

I don't know if the demigods of usage have pronounced on this issue or not since I pay no attention to them, so I don't know if she got this silly idea from them, but she didn't cite authority as the basis for her views; she cited her incorrect semantic theory. Evidently she was not familiar with the Constitution of the United States, whose Preamble reads:

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.This is not only grammatical; it is elloquent. I can only endorse Linda Monk's proposal that the Preamble would be a far more suitable recitation for schoolchildren than the Pledge of Allegiance. Unlike the Pledge of Allegiance, it is not offensive to atheists, cannot be considered idolatrous, and expounds the values on which the United States was founded.

Omit stupid grammar teaching

I talked recently with an undergraduate who told me something about her grammar instruction in the Los Angeles public schools. And in addition to the usual nonsense about not ending sentences with prepositions and never using "contractions" and things of that sort, she told me a new one. She was told that sentences like the one you are now reading are ungrammatical.

The alleged fault I'm alluding to here does not have to do with the fact that the main clause is passive, though I have often encountered absurd over-applications of the notion that passives must be avoided, so that would probably have been considered a second strike against it. No, the red sentence above has another feature that is supposed to be a grammatical sin. Sit awhile and try to figure out what, before you read on.

What my undergraduate student's high school English teacher insisted on was that you should look at any sentence containing the subordinator that and see whether omitting it would leave the sentence still grammatical. If so, then you must omit it, this teacher said. She would grade you down if you ever used that where grammar did not absolutely require it.

Think about that. The teacher is saying that these famous lines by Joyce Kilmer are ungrammatical:

I think that I shall never see

A poem lovely as a tree

She is saying the same about the first sentence of Wuthering Heights. And so on and so on. This is worse than bad English teaching. This is raving, blithering nonsense.

But I think I know where it comes from. I think it originates in an elevation of a stupid mantra to the status of a holy edict. The mantra is "Omit needless words," stated on page 23 of Strunk and White's poisonous little collection of bad grammatical advice, The Elements of Style, and elaborated on by E. B. White in the reminiscences of his introduction. It could be interpreted in a sensible way as a piece of advice for those editing their own writing: make sure you're not being too wordy (e.g., why say on a daily basis if you're trying to keep to a length limit and the phrase every day is shorter). But the teacher must have decided that the Strunkian imperative had to be obeyed literally and without question at all times, and that punishment must be meted out to those who do not obey. Fascist grammar.

If I have one ambition for my professional life, it is to do something to drive back the dark forces of grammatical fascism of this kind, to help get English language teaching back into a state where the things that are taught about the grammar of the language are broadly the things that are true, rather than ridiculous invented nonsense like that all words are forbidden except where they are required.

Feint of heart

Nicole at A Capital Idea links to my post on participial relative clauses with whom, calling it "interesting". She adds a cautionary coda:

Warning: not for the feint of heart.

Since Nicole indentifies herself as "A newspaper copy editor [who] talks shop and invites you to do the same", I'm going with the hypothesis that the eggcorn was ironic.

Google reports 3,910 hits for "feint of heart", so it's a 3,910 whG pattern, weighing in at 912 whG/gp. By comparison, "faint of heart" comes in at 151,000 whG, or 35,238 whG/gp.

Score: correct spelling 39, wrong spelling (or irony) 1.

Proportionally speaking, that is.

In Memoriam

We don't usually post things here without a language hook, so in honor of Memorial Day I'll just put up a link to a post that I wrote last fall for Veterans Day -- though the language hook was vestigial at best -- and another to a (more linguistic) post about military modal logic.

Hey folks, "passive voice" != "vague about agency"

We've seen several examples of people who think that "passive" means "without an explicit agent". Here's another example, from Phil Dennison's weblog.

Dennison quotes the lede of an AP story:

Prosecutors dropped their case Friday against a security guard in the 2000 death of a man put in a choke hold during a shoplifting investigation — a case that took on racial overtones.

and complains that "[i]t just 'took them on,' out of the ether or the phlogiston, I guess. Just like that. Nobody’s fault, really". Dennison points out that you have to read to the end of the AP story to learn how the overtones arose, namely because of protests led by Al Sharpton. The linguistic criticism is fair enough. It's a political question whether raising the racial issue was to Sharpton's credit or due to his "fault", but either way, his agency deserves to be placed higher in the story.

However, Dennison starts his post by writing "Here is a great example of how to mislead readers by using the passive voice", and ends "Don’t use the passive voice in news stories, kids. Especially in news stories about people doing things to other people. It’s really, really dishonest."

Ironically, there's only one instance of the passive voice in the offending sentence, and it's not the one that Dennison complains about. He's annoyed about "a case that took on racial overtones", which involves an ordinary active use of the verb take, in the past tense. Removing the relative clause and making the subject definite for clarity, we get:

The case took on racial overtones.

A passive version -- at best marginally possible for me -- would be

?Racial overtones were taken on by the case.

The actual passive in the AP's lede is in the phrase

a man put in a choke hold during a shoplifting investigation

Again removing the (implicit) relative clause ("a man (who was) put in a...) and making the subject definite, we get

The man was put in a choke hold during a shoplifting investigation.

An active version would be

[Someone] put the man in a choke hold during a shoplifting investigation.

Ironically echoing Dennison's ironic complaint, we could say "he just was 'put in a choke hold' out of the ether? Just like that. Nobody's fault, really."

I don't know anything about the facts of this case, and I'm not trying to take sides for or against either Sharpton or Dennison. The AP story's lede choses to be vague about two questions of agency -- who choked the alleged shoplifter to death? and who raised the issue of race in connection with the case? But the AP writer achieves this vagueness by using the passive voice in only one of the two cases -- and it's not the one that Phil Dennison complained about.

Red vs. Blue reloaded

Kevin Drum at Washington Monthly posts a map of red vs. blue counties, and asks his readers "Can you guess what this map represents? Click the graphic for the answer if you give up. Hint: it's got nothing to do with politics." More discussion is here, here, here, here, and so on. A larger version of the map is here ( created by Matthew T. Campbell at East Central University in Oklahoma, based on a data from a survey by Alan McConchie located at this site). A larger (and more scientifically interesting) set of similar maps, presenting data gathered by Bert Vaux and others, can be found here.

[Kevin Drum link via Erika at KDT]

[Prior postings by Kerim Friedman (May 28) and and Irish Eagle (May 25).]

Another overnegation opportunity: yet vs. yet to

Glen Whitman of agoraphilia emailed to ask

You ended your post on the poetry of Rumsfeld with the following: "No one, as far as we know, has yet set to music the press releases of the Plain English Campaign." Isn't that one of those "double negations" you and your co-bloggers have discussed in some recent posts?

After all, I for one have not set those press releases to music, which means you can't (on a literal interpretation) say that *no one* has yet to do so.

I make plenty of mistakes -- although the rumor that Geoff Pullum gets teaching relief from UCSC in return for editing my posts is not true -- but I'm innocent in this case. The cited sentence wasn't a case of overnegation, because there's a difference between "(not) have yet V+en" and "have yet to V", and I used the first of these rather than the second.

Here's (the relevant bit of) the AH Dictionary's entry for yet:

1. At this time; for the present: isn't ready yet. 2. Up to a specified time; thus far: The end had not yet come.

We can just substitute "at this time" or "for the present" into the cited sentence, to clarify the meaning at the expense of complicating the form. Maybe "up to the present time" would be even clearer:

"No one, as far as we know, has up to the present time set to music the press releases of the Plain English Campaign."

That's just what I meant, and it has just the right number of negatives in it.

GW was thinking of a different usage of yet, which the OED gives as sense 2.c.:

2.c. Followed by an infinitive referring to the future, and thus implying incompleteness (e.g. yet to be done, implying ‘not hitherto done’; I have yet to learn, implying ‘I have not hitherto learnt’). Cf. also 5.

This yet is not a polarity item, but it does imply a negative:

(a) Kim has yet to arrive ⇔ (b) Kim has not yet arrived

My sentence was of type (b), but GW interpreted it as being of type (a) with an extra negative. In this case, I wasn't guilty -- but because this misinterpretation is only one little "to" away, at least with a verb like set whose past participle is the same as its bare stem, I probably should have chosen another wording.

Certainly plenty of others have made the mistake that GW attributed to me. There are 3,820 Google hits for "no one has yet to" -- that's 3,820 whG, or 891 whG/gp -- and all of those that I checked are overnegations (except for one or two that I couldn't understand):

(link) While no one has yet to describe England as the anti-Christ they have come close.

(link) No one has yet to compare these findings to possible early symptoms in men.

(link) ..no one has yet to beat my $12,000 pc

(link) The property... has been advertised for sale for nearly a year and a half, and no one has yet to purchase it

(link) No one has yet to figure out why ... they got it in their heads to film a "real lemming migration" ...

(link) No one has yet to sign on to star in the film.

etc., etc.

So we can add "no one has yet to" to the case of " fail to miss", as an example of a phrase that is almost always used to mean the opposite of its compositional meaning.

I guess that " construction grammar" implies that this is possible and even normal, but it still seems like a mistake to me.

A couple of other "yet" notes in passing.... We ought to be able to unify the AHD's two senses of this yet with a somewhat more abstract definition: "up to an implicitly specified time", where the time can be past (sense 2) or present (sense 1). The OED does this with its sense 2.a.:

2. a. (a) Implying continuance from a previous time up to and at the present (or some stated) time: Now as until now (or then as until then): = STILL adv.

This yet has become a "polarity item" (though other senses have not): the AHD's examples are negative for a reason. We no longer say "It's ready yet" meaning "it's still ready" -- we only say "it's not ready yet" or "is it ready yet"? There are plenty of other interesting semantic issues associated with the word yet, not least the question of how far to go in unifying its protean spread of structures and senses. Not all of the examples below are currently colloquial, but it's just as important to explain what we don't (or no longer) say, as what we do:

He may yet change his mind.

The Sekhti came yet, and yet again.

My sandals were worse yet.

Averse alike to Flatter, or Offend,/Not free from Faults, nor yet too vain to mend.

The tracks include..‘To Know Him is to Love Him’ (with David Bowie on saxophone, yet!).

A yet-warm corpse, and yet unburiable.

The swampy patches of yet unreclaimed forest.

This is the queerest thing yet!

Are we there yet?

Even yet not quite finished.

O merchants, tarry yet a day Here in Bokhara.

But there were..extensions of this practice as yet but little noticed.

As yet the Duke professed himself a member of the Anglican Church.

He was one of the numerous party of yet walkers in the world.

In the yet non-existence of language.

The splendid yet useless imagery.

Though his belief be true, yet the very truth he holds, becomes his heresie.

Surely I could always be that way again, and yet/ I've grown accustomed to her looks...

(quotes mostly but not all from the OED's citations)

A Prison Riot Over Strict Transitivity

Well, O.K., not a full-scale riot, but for a few minutes there I wondered if I was about to be in the middle of one. This happened years ago, but I was reminded of it by the recent Language Log posts on Strict Transitivity. I was teaching Introduction to Linguistics at a local maximum-security state prison in Pittsburgh, for the University of Pittsburgh's earn-a-degree-in-prison program, and my co-teacher and I had arrived at the topic of transitivity.

We asked the students whether some verbs had to be transitive. Yeah, a couple of them said, some verbs are only transitive. Like what? Well, there's find, that 's always transitive. No, said another student, you can use find intransitively. "NO you can't!", said the others. "YES YOU CAN" (he was shouting by this time), you can say "I looked all over the house for it, but I didn't find there, and finally I found in the yard." "NO YOU CAN'T!" (a growing number of the other twenty or so men in the class also began shouting) "THAT'S STUPID!" The holdout leapt to his feet and started waving his arms around: "YOU CAN TOO! YOU CAN FIND HERE, FIND THERE, IT'S INTRANSITIVE, IT'S FINE!" "OH NO IT ISN'T!" But at least the others stayed in their seats, so in the end Sasha and I did not have the opportunity to find out if the instructions we'd been given during the required orientation for working in the prison could actually be carried out ("In case of a threatening disturbance, show no fear, walk calmly to the wall and summon help by pressing the red button there"). (Yes, there was an actual red panic button attached to the wall of each classroom in the prison school.)

This incident left me with two main reactions. First, while it was in progress I envisioned the newspaper headlines -- "Volunteer Teachers Injured in Prison Riot over Transitivity" -- and thought that maybe that would finally convince the general public of the importance of training in linguistics. And second, I realized that I will never, never, never see a class of ordinary undergraduates getting so excited about a bit of language structure. It's not that I yearn for classroom riots, but I sure wouldn't mind transplanting some of the intellectual enthusiasm of my inmate students to my regular classrooms. (I've tried telling my classes that I wish they were more like prison inmates, but this doesn't seem to have the desired effect.)

May 30, 2004

Just as good for hate

It was the words "in Arabic" that truly shocked me. The source: Jeffrey Goldberg's long article "Among the Settlers" in the May 31 New Yorker (related slide show with audio here). The scene: outside Hadassah House, home to several families of Jewish settlers in Hebron, across the street from the Córdoba School for (Palestinian Arab) girls.

A group of yeshiva students appeared, walking in the direction of the Tomb of the Patriarchs. ... They had the wispy beards of young men who have never shaved.

Two Arab girls, their heads covered by scarves, books clutched to their chests, left the Córdoba School, and were walking toward the yeshiva boys.

"Cunts!" one of the boys yelled, in Arabic.

"Do you let your brothers fuck you?" another one yelled.

Raw, hostile, poisonous, overt, sexually-charged, ethnic hatred. And these young Hebrew-speaking men, isolated by soldiers from virtually all contact with Arabs, had taken the trouble to learn enough Arabic to be able to howl their filth in their victims' native language.

So many people talk about the need to speak a common language so that we can all get along — the dream of Esperanto. Never think that sharing a language is either a necessary or a sufficient condition for being able to empathize with other human beings or to treat them with humanity. The key difference between human language and, say, the hyperspecialized dance "language" of honey bees is that a human language can be used for propositional communications of any sort. They are infinitely adaptable. They are just as good for expressing hate as for anything else.

Dog Latin of the day

Tom Friedman starts his NYT column today with this: "The American public has been treated to such a festival of mea, wea and hea culpas on Iraq lately it could be forgiven for feeling utterly lost."

In these latter days, that's about as good as we're going to get. For a glimpse of Dog-Latin as it once was, see Stevens' definition of a kitchen, from the entry for Dog-Latin in E. Cobham Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable:

As the law classically expresses it, a kitchen is "camera necessaria pro usus cookare; cum saucepannis, stewpannis, scullero, dressero, coalholo, stovis, smoak-jacko; pro roastandum, boilandum, fryandum, et plum-pudding-mixandum ..." A Law Report (Daniel v. Dishclout).

[Update: John Kozak emails:

The UK satirical magazine "Private Eye" has a running Dog Latin feature called "That Honorary Degree Citation In Full". Not online, sadly (as far as I know), but here's the current issue's offering:

SALUTAMUS BEII GEII TRES FRATRI CANTORES IN VOCE FALSETTO NOMINE BARRIUS, ROBINUSQUE ET MAURICIUS EHEU NUNC MORTUUS (QUONDAM UXOR 'LULU', DIVA CELEBRATISSIMA GLASWEGIENSIS CUM CARMINE POPULARE 'CLAMATE!') TRANSFORMAVERUNT MUNDUM MUSICAE DISOTECHNIS CUM JOHANNES TRAVOLTUS HOMO IN TUNICO BLANCO IN ARTEFACTO CINEMATICO 'FEBRUM NOCTIS SATURNALIS'.

John adds that

Now I come to think of it, more contemporary Dog Latin can be found in the spells in the Harry Potter books, of course (the Latin translation of HP&TPS leaves the spells "untranslated": they should be in mangled Greek, it seems to me).

]

Plummy

Americans' accents may be " flat", but at least they're not "plummy".

According to a 1999 BBC News article, Radio 4 is said to have dumped an announcer for excessive plumminess:

Outspoken journalist Boris Johnson claims he has been the victim of discrimination because his accent is too "plummy". ...

The Daily Telegraph columnist and newly-appointed editor of The Spectator magazine believes he has been the victim of what he calls "vocal correctness".

The article goes on to relay the suggestions of Gregory de Polnay, head of voice at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art, about how Johnson could "reinvent" his accent:

He said the journalist's voice was that of someone "used to commanding, used to being heard".

Standardising Johnson's vowel sounds would be the first hurdle.

"All those rather clipped vowel sounds that go with that accent we could iron out," said Polnay.

It's interesting that the BBC can write without irony about "standardising" someone's Received Pronunciation vowels. And to talk about "ironing out" vowels makes it sound like they are not "flat" enough -- is there a translatlantic flatness continuum here, with Americans having too much of it, and upper-class Brits not enough? De Polnay adds that

Johnson's "nasality" would also have to be addressed, ensuring he does not push the sound of his voice down through the nose.

"Somewhere along the line somebody has said that [nasal] sound can appear to be more authoritative," he said.

Perhaps it's pushing sounds "down through the nose" (from where?) that makes them "plummy"? But he OED is quite specific about what plummy means, and the nose is not mentioned:

1. Consisting of, abounding in, or like plums.

2. fig. a. Of the nature of a ‘plum’; rich, good, desirable.

2.b. Of the voice, then of sound gen.: thick-sounding, rich, ‘fruity’; indistinct; with bass predominating.

However, the citations for sense 2.b., which go back to 1881, seem to refer to personal or stylistic characteristics, or even the sound of certain kinds of amplifying circuits, rather than to social class. Class aside, it's clear that sometimes plumminess is a Good Thing and sometimes (despite sense 2.a.) not:

1881 Punch 23 July 25/2 The same aged lover was bidding, with rather a ‘plummy’ voice, the More-than-Middle-Aged Heroine ‘good bye for ever’.

1947 Jrnl. Inst. Electrical Engin. XCIV. IIIA 446/1 Such distortions can be tolerated..without serious loss of articulation, though the speech will usually sound rather ‘plummy’ and unnatural.

1951 K. HARRIS Innocents from Abroad 199 The rich, plummy voice of [actor] Edward Arnold.

1955 Times 3 May 14/4 A disc which sounds plummy and muffled in tone.

1965 G. MCINNES Road to Gundagai xi. 197 His voice..was wonderfully plummy and Edwardian.

1970 Daily Tel. 1 Sept. 9/5 All India Radiomodelled..on the BBC, even down to the plummy accents of its announcers.

1975 City Press 1 May 16/5 Her duchess on the make is a finely pointed performance, the plummy vowels contrasting splendidly with consonants periodically marred by the lack of false teeth.

1977 Early Mus. Oct. 549/3 The plummy..tone [of Flemish virginals] is evidently more popular than the musically versatile but astringent Italian virginal.

1978 Gramophone Feb. 1439/1 His tone is mellow, but again, as in the Waltzes..the sound sometimes seems a bit plummy and close.

In contrast, the Boris Johnson story emphasizes class associations, and so do most of the comments in a forum devoted to Brian Sewell's candidacy for being "more annoying than Mick Hucknall". The nomination features the plumminess of his accent as a key source of annoyance:

First, his unfounded acid criticism of just about everything: "Oh, of course one cannot take Mozart seriously, since he didn't have an overblown plummy accent like one's own."

Second, his overblown plummy accent. Like Jeremy Spake, I suspect that this is a deliberately exaggerated affectation which makes up for his lack of other noteworthy features.

The other forum commenters echo the class associations:

...vain, self obsessed snobby little bastard...

posh talking bastard. thinks he is better than anyone else.

Sewell acts as if he's little lord Fontleroy.

Just because he went to Public school and practiced Received Pronunciation behind the bike sheds ... doesn't make his opinion any more valid than any other yobbo.

I've got Brian Sewell down as a massive wind-up merchant.

The plummy voice CAN'T be real [...] & his comment on the subject of common people, other cultures, non-arty types etc. are just inflammatory for their own sake... As for posh? Nah, not with a name like Brian...

For those who (like me) have never heard of Brian Sewell, here's an (allegedly typical alleged) transcript, showing the content as opposed to the accent:

'Brian Sewell': "So, how does one get to Gateshead?"

Gatesheed Coonsil: "Well, you can take the train out of King's Cross..."

'BS': "The train?! and travel with.... *the masses*....?!?!"

GC: "I think you'll find that's what everyone else does..."'Brian Sewell'": "I've heard that Gateshead is merely a small village, an insignificant backwater inhabited by uneducated, illiterate neanderthals who still live in caves? Is that true?"

Coonsil: "Naah, I think you'll find that's Sunderland."

You can check out the accent as well as the content in more detail on this Brian Sewell satire (?) site, where you'll find that his voice is not at all "plummy" in the OED's sense of "thick-sounding ... with bass predominating". Yet people today seem to accept "plummy" as a description of his way of talking, suggesting that it's the social class rather than the sound quality that has become primary.

[Note for Americans who (like me) don't follow British politics very closely: Boris Johnson has not suffered too much after losing his Radio 4 gig: Simon Hoggart wrote a few days ago in the Guardian that "in the fullness of time [Boris Johnson] will probably become prime minister". So apparently plumminess is not terminally out of fashion in the U.K. -- assuming, as I do, that Johnson did not take Gregory de Polnay's 1999 advice. I'm not sure whether Hoggart is serious, however, since most of his article deals with aspects of British culture that are opaque to me, such as what it means that Johnson "produced a used envelope and tossed it onto the table of the house", or why Mickey Fabb "will be polishing [Boris'] bat with linseed oil".]

[Update: Margaret Marks emailed a comment on Brian Sewell:

I absolutely agree that his voice is not what's usually called plummy.

Sewell was the boyfriend of Ant(h)ony Blunt, the Keeper of the Queen's Pictures who turned out to be Philby's third (or fourth?) man, i.e. a spy for the Soviet Union. I think he was about 80 when the news came out. His house was surrounded by journalists, who were dealt with by Sewell, unknown at that time, who obviously loved the limelight and had a variety of longwinded ways of saying 'No comment'. He does or did camp it up a lot, though. Deliberately exaggerated, as you say. A very upper-class accent.

A couple of relevant links are here and here.]

Strict transitivity

It sounds like Geoff's recent posts on transitive verbs have inspired a flood of activity in which people are seeking real linguistic examples related to a syntactic phenomenon, and that's all to the good. However, a quick perusal of the discussion suggests that people are taking an overly simplistic approach to the phenomenon in question.

There is a whole body of literature, dating back at least to Fillmore's work on definite and indefinite null complements, demonstrating that it is dangerous to think of the presence -- and particularly the absence -- of direct objects as a single phenomenon. For a start, "Habitual" or "characteristic" uses are well known to permit even the most classicially "rigidly transitive" verbs to appear without an object ("Pussycats eat, but tigers devour"); in addition, a verb's degree of flexibility with respect to omitting objects is influenced by aspectual considerations and the strength with which it selects the semantic category of its argument. Discourse factors can play a role as well.

All this is to say that "transitivity", in the sense of a dictionary's v.i. versus v.t., or in the sense of strict subcategorization frames, is not all it's cracked up to be, and it hasn't been for quite some time, at least to lexical semanticists who work at the interface with syntax. I haven't done a careful analysis, but the counterexamples being sent to Geoff seem like they fall into categories we already knew about.

I would say more, but theoretically this is a holiday weekend and I'd rather spend my time playing than discussing.

Flat Yanks, sharp Brits?

On May 14, when Bob Mondello reviewed Troy on NPR, he said:

"As with most sword-and-sandal epics, go indoors and everything's suddenly about statuary, and torches, and an international cast that's trying to reach common ground on accents; here the kings hail from Scotland and Ireland, and the followers from London's West End and Australia. Happily this makes Pitt's Achilles sound like the outsider he's supposed to be, even when he remembers to round his vowels..."

On the same date, when Carrie Rickey reviewed Troy in the Philadelphia Inquirer, she wrote

"Just because Pitt is a hair actor, tossing highlighted tresses for emphasis, doesn't mean he's a bad actor... But when Pitt opens his mouth, the voice that emerges is prairie-flat, lacking the thunder-on-the-palisades sweep and resonance of O'Toole and Bana. When Pitt speaks, you don't think Troy; you think, as a friend says, Troy Donahue."

There seems to be some sort of dialect=shape metaphor in the background here: American voices are flat, British (and Scottish and Australian) voices are not.

Although I suggested in an earlier post that Mondello might have been referring to Pitt's artificial r-lessless, that's probably not it. There a whole complex of inter-related semi-synesthesias going on here, several different metaphorical extensions of "flatness" -- to sounds, to articulations, and especially to social evaluation.

An IMDB review of the 1955 movie Seven Cities of Gold complains about Richard Egan as "Jose Mendoza" that

Egan is about as Spanish as William Bendix!! His flat American accent and obviously non-Latin coloring create a sensory paradox when he is onscreen.

A bit of Googling will turn up hundreds of other examples of this sort of thing. But what is flat about American accents, exactly?

A flat voice might be one that is emotionless or uninflected, and American speech is stereotypically uninflected by comparison to British speech. It's easy to find lists of (empirically unsupported) national stereotypes that depict Americans (especially men) as using little intonational modulation, for example this one:

These are some of the more commonly-held ideas about different cultures: German men speak fairly slowly, with a deep voice; everything sounds serious! Scandinavians appear more quiet and modest: soft, gentle tones but with clearly varied intonation. Italians, Spanish and Greeks always seem to be excited about something. Americans “chew” their words and frequently have very deep voices with “flat” intonation.

However, often it's the vowels or consonants rather than the intonations that are perceived as "flat", as in Mondello's review, or this Wired article about call centers in Bangalore:

"You try to place the accent. Iowa maybe? No, the "a" sound is too flat. California? Maybe it's a crowded call center in some business park in Kansas City.

But Betty is actually calling from Bangalore, and her real name is Savita Balasubramanyam. ... And her perfect American accent is the result of rigorous training and an employer-encouraged addiction to Ally McBeal."

Then again, this interview with Tom Friedman about his visit to call centers in Bangalore features a clip of an "accent neutralization class" in which the instructor uses the phrase "flat the 'tuh' sound" to mean "flap and voice prevocalic non-pre-stress /t/":

INSTRUCTOR: All right, class. I want you to take out your books and I'm going to give you a passage. Remember, the first day I told you that the Americans flat the "tuh" sound. You know, it sounds like an almost "duh" sound, not keep it crisp and clear like the British. So I would not say "Betsy bought a bit of better butter" or "insert a quarter in a meter." But they would say "insert a quarder in the meder," or "'Beddy bought a bit of bedder budder."

So I'm just going to read it out for you once, and then we'll read it together. All right? "Thirty little turtles in a bottle of bottled water. A bottle of bottled water held 30 little turtles. It didn't matter that each turtle had a round metal ladle in order to get a little bit of noodles." All right, who's going to read first?

Friedman explains that the same instructor

...also does British accents, American accents. That was actually for a Canadian call center. They were actually working on a sort of flat North American Canadian accent.

where he is not talking about T's but about some overall impression of flatness.

A discussion of accents in Hebrew suggests that American R's are "very flat":

"Don't worry about how you sound" was my mother's advice. She had heard a political talk in Hebrew on the radio, by someone whose masculine sounding voice spoke with a heavy American accent, including very flat "r"s. After the speech, the announcer said: "You have just heard Golda Meir speak." My mother suggested: "Listen to how she speaks. She's prime minister of Israel and her Hebrew sounds so American."

Flat vowels, flat T's, flat R's, flat accents. What are these people talking about?

As usual, reading the OED helps us to trace the metaphor back to its sources, which turn out to be multiple. Among the OED's senses for flat (the adjective) are:

4.b. Engraving. Wanting in sharpness...

4.c. Of paint, lacquer, or varnish: lustreless, dull.

4.d. Photogr. Wanting in contrast.7. Wanting in points of attraction and interest; prosaic, dull, uninteresting, lifeless, monotonous, insipid. Sometimes with allusion to sense 10. a. of composition, discourse, a joke, etc. Also of a person with reference to his composition, conversation, etc.

9.a. Wanting in energy and spirit; lifeless, dull.

10. Of drink, etc.: That has lost its flavour or sharpness; dead, insipid, stale.

11.a. Of sound, a resonant instrument, a voice: Not clear and sharp; dead, dull. Also in Combs., as flat-sounding, -vowelled.

11.b. Music. Of a note or singer: Relatively low in pitch; below the regular or true pitch.

There are several different metaphors here: "flatness is lack of variation"; "flatness is lack of some (desired) feature"; "flatness is lack of attractiveness"; "flatness is lack of resonance"; "flatness is pitch lowered relative to a reference value". All of these can be applied to sound.

There is a tradition (now obsolete) in phonetics of using "flat" (usually as opposed to "sharp") to describe certain differences in sound quality. For example, the OED cites

1874 R. MORRIS Hist. Eng. Gram. §54 B and d, &c. are said to be soft or flat, while p and t, &c. are called hard or sharp consonants.

This is the sense of "flat" as "voiced" (i.e. accompanied by vocal-cord vibration) that the call-center instructor in Bangalore employed, carrying on the tradition of 19th-century British phonetics, which was developed largely in order to help teach "commercial millionaires" and colonial subjects to speak "properly."

The OED also references two other similarly-abandoned traditional uses of "flat" in phonetics. One, due to Henry Sweet, refers to vowels made with a level or "flat" tongue shape, not raised or lowered in either the back or front:

1934 H. C. WYLD in S.P.E. Tract XXXIX. 609 The tongue may be so used that neither back nor front predominates, but the whole tongue, which lies evenly in the mouth, is raised or lowered. Vowels so formed are called ‘mixed’ by Sweet, but I owe to him also the term ‘flat’ which I prefer as more descriptive. The vowel [ʌ] in bird is low-flat.

The other one is due to Jakobson, Fant and Halle. This one refers to sound rather than tongue shape, invoking the contrast with "sharp" again, but in terms of physical measurements of frequency rather than subjective impressions of sound quality:

1952 R. JAKOBSON et al. Prelim. Speech Analysis 31 Flat vs. Plain...Flattening manifests itself by a downward shift of a set of formants.

However, I think it's clear that the references to "flat American accents" don't describe anything at all about the intrinsic quality of the sounds, but are pure social evaluation: "wanting in points of attraction and interest; prosaic, dull, uninteresting, lifeless, monotonous, insipid". The American middle classes have always had self-esteem problems.

May 29, 2004

The poetry of Donald Rumsfeld and other fresh American art songs

As we know,

There are known knowns.

There are things we know we know.

We also know

There are known unknowns.

That is to say

We know there are some things

We do not know.

But there are also unknown unknowns,

The ones we don't know

We don't know.

This and six others songs with lyrics by Rumsfeld are available on CD here. No one, as far as we know, has yet set to music the press releases of the Plain English Campaign. [via kaleboel].

Natural language and artificial intelligence

I hesitate to say a good word for modern software (it might encourage the further production of the sort of bug-ridden word processors I use so much), but I think Craig Silverstein (Google's technology director), in the interview that Mark Liberman recently cited, might actually be underestimating recent successes at simulating aspects of common sense. Try typing "Simmons" and "Beautyrest" into the Google search box (notice, no use of the word mattress) and watch the mattress ads spring up in the margin of your display of search results. If that isn't effective computer simulation of common sense I don't know what would be: the name Simmons is common enough (one might imagine it thinking), but there is a Simmons firm that has trademarked the name Beautyrest, and it's the name of a line of mattress products, so...

The classic dreams of GOFAI (Good Old-Fashioned Artificial Intelligence) may have been quixotic. But the work on impossible projects about replicating common sense (like inferring in context that someone who goes into a restaurant probably intends to eat a meal there, and will be paying for it, and so forth) used programmers who stayed in the business and ended up working on more sensible things that turned out to be considerably more successful. Google's subject-linked advertisements really do quite often turn out to be relevant, even if you do get silly mistakes based on superficial word similarities sometimes. This is not GOFAI, but it is reasonably called AI, and it is not completely brain-dead. I'm fully aware that what's really going on may be just a matter of mattress-sellers including words like Simmons and Beautyrest on the lists of words that they pay to have their ads associated with, which renders it almost stupidly simple; but my point is not that wondrously clever techniques of reasoning are really being used, but rather that it takes so little of this sort of elementary rigging and accessing of files and lists to make it appear that the system is intelligently responsive to one's interests, and the folks at Google are doing it quite well.

And it's not just Google. Yesterday I checked the details of a book on Amazon.com and I noticed that not only did it have some suggestions for me about the usual kinds of books I buy, it also asked me if I would like the book I had just looked up to be delivered to me the next day, and told me that if I placed my order within one hour and ten minutes that could be done. While I stared at this, the screen did a sudden update and "one hour and ten minutes" changed to "one hour and nine minutes". Now, the software accomplishment involved shouldn't be compared to to proving Fermat's last theorem, but looks intelligent. It's a closer approach to helpful, relevant, and timely information than I've had in most phone calls to retailers.

What is notable about these advances in advertising and retailing software, though, is that the symbolic computational linguistics of the 1980s has contributed nothing to them. None of the small wonders of convenience and user-friendliness found on the very best of the commercial websites involves anything you could reasonably call natural language processing.

(I know, I know, AskJeeves.com boasts of natural language processing, and says its product is "able to understand the context of what you are asking" and can offer "answers and search suggestions in the same human terms in which we all communicate". Puh-lease! can you say pa-thet-ic? Ask Jeeves "Show me some cars that are not Japanese." The results are all about Japanese cars. The NLP claims about AskJeeves appear to be a load of nonsense.)

Perhaps Silverstein is right to talk in terms of it being centuries before you can talk to a computer at the library reference desk and find it as intelligent as the human being who currently staffs it. But I'm not prepared to concede that yet. I think in due course we have to get back to real natural language front ends: it is possible to pull together (1) literal sentence understanding based on grammatical analysis, and (2) modern computational techniques of spotting likely relevance. But no one is trying to do it at the moment.

The people working on (2) are doing brilliantly. (Notice, the spotting of likely spelling mistakes in Google and advanced word processors is an aspect of (2), and deserves some real respect.) But work on (1) was all but abandoned in industry some ten years or more ago. It didn't have to be. Nothing was discovered that made people decide syntax or literal meaning were impossible to grapple with algorithmically. I am not ready to believe that centuries will have to elapse before I can send email to a shopping robot "Get me price information on Simmons Beautyrest mattresses from at least five stores in Northern California" and get some useful data back in response. Sure, there are some syntactically irresolvable ambiguities in there (is it mattresses from five stores, or information from five stores?). But Google's ad-relevance technology could pretty much figure out what I want even without analyzing the grammar. If we brought even just a little grammar together with some educated guesswork and smart search technology, we could have something really remarkable. Not intelligence and empathy — we're going to be talking about something vastly less intelligent than a cockroach here, and an equivalent level of empathy, i.e., none — but it could still be something very effective, something that you could easily mistake for rapid and effective assistance from an intelligent entity that had understood the gist of what you said.

Brad Pitt in Troy: r-lessly round or r-fully flat?

Erika at Kittenishly Doomy Thoughts asks

What the hell was up with Brad Pitt's accent in Troy? It seemed to be entirely devoid of postvocalic /r/, but he didn't have any.. other.. features of r-less dialects. It sounded like some sort of affectation, but I had no idea what he was hoping to convey with it.

Could this have been what Bob Mondello was talking about on NPR when he said that "Pitt's Achilles [sounds] like the outsider he's supposed to be, even when he remembers to round his vowels"?

A lot of people are talking about how Brad Pitt talks, but so far, Erika is the only one (among those I've read or heard!) who's said anything specific and coherent about it. Here's a small fraction of the Brad Pitt accent discussion from (here and there in) FT forums:

Kithy: I'm totally going to see this. I don't care who's in it or how lame Brad's accent is...

Elle Driver: I am so gonna be there all those pretty men in skirts, I was laughing at Brad's accent during the trailer though...

Sharmila: What is UP with Brad Pitt's accent? It's not just me who starts cracking up during the trailer, right?

M One: And yes, even in the short previews, Brad's accent slippage is pretty bad. Skirts outweight accents for me though.

Talamasca: Oh good, I thought I was the only one who thought Brad's accent was lame in the commericals/trailer.

Satine O'Hara: It looks like an amazing film to me- besides Brad Pitt's accent which can be described as shaky at best...

Jcpdiesel21: I am very frightened of Brad Pitt's accent.

radguurl: ...Brad Pitt's terrible, terrible, terrible accent.

Knesaa: I rather liked Brad Pitt's Achilles also, shitty accent or no.

Cassandra423: Good thing he had those fabulous muscles to distract me from his horrible accent.

Sally Albright: From the trailer, I was concerned about his accent, but in the movie it wasn't that bad. Or maybe I become accustomed to it.

Elle Driver: I liked Brad Pitt as Achellies, but his accent was really, really bad

Binky: The accent didn't even bug all that much. I liked him. Not exactly a shining performance, but he wasn't the stand-out suckage of the film.

If I have a chance later on, I'll see if I can grab some Pitt accent audio from the online trailers -- so far all I can remember hearing, in a couple of TV ads, is the musical background for fleets of ships and flashes of battles.

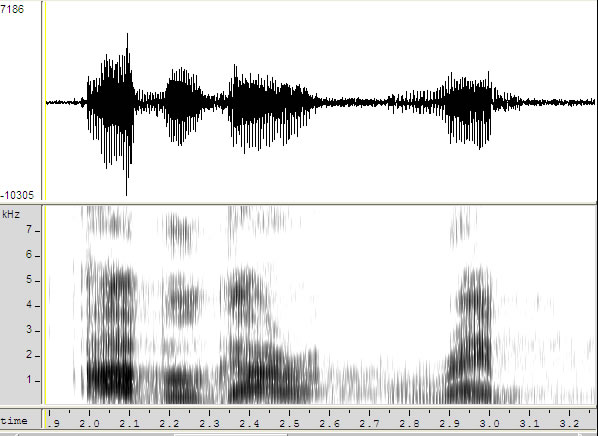

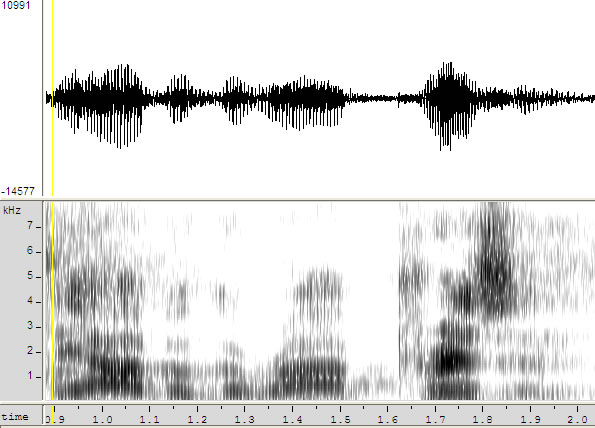

[Update: Here are .wav files for Pitt's contributions to the scene in which Agamemnon confronts Achilles over possession of Briseis. Pitt is indeed consistently r-less in this scene, just as Erika says. So when Mondello said "round his vowels", did he mean "leave out syllable-final r's"?

(link) Perhaps the kings were too far behind to see.

(link) The soldiers won the battle.

(link) Be careful, king of kings.

(link) First you need the victory.

(link) You want gold? Take it.

(link) It's my gift. To honor your courage -- take what you wish.

(link) No argument with you, brothers, but if you don't release her, you'll never see home again.

(link) Decide!

There are some other interesting things about Pitt's speech in this scene, which I'll have to pick up later, as my youngest son and I are off to the zoo at the moment.]

May 28, 2004

Squelch squelched, predecease whacked, induce terminated

Proposed strictly transitive verbs have half-lives as short as synthesized high-end transuranic elements. Lance Nathan at MIT squelches Adam Albright's suggestion squelch with a sentence off the web (http://thalo.net/freedom.html): "I have been a participant in other online forums, grew dissatisfied with the rampant tyranny of political correctness and impulse to squelch, and therefore acted to whack together my own modest forum site." So much for squelch. He also kills predecease: "Where the husband predeceases, neither widow nor children can claim a right in any part of the heirship moveables" (Erskine, Inst. Law Scot., 1765, via OED). And M. Crawford writes with this example of induce with implicit object: "I'm really hoping I go before they have to induce because I've heard so many bad things about induction and how much more painful it is." (That's, about inducing labor to hasten childbirth, of course.) So, though one could quibble, that looks like three of Adam Albright's potential strict intransitive verbs gone. And more counterexamples are coming in over the transom all the time.

Garfield learns about directives

The traditional statement about imperative clauses is that they express commands: they are for bossing people around, telling people what to do. This is not so. Imperatives express a much wider range of meanings, referred to in The Cambridge Grammar as directives. In today's Garfield cartoon strip (May 28, 2004) the difference comes out clearly.

"Nobody tells me what to do!", Garfield is thinking.

Then his owner/servant Jon appears with a heaped platter and says, "Have something to eat."

And the gluttonous cat says to himself, "Well, this is a bit awkward."

Not at all, Garfield. Tuck in. Jon's utterance is (syntactically) an imperative, but it is not (semantically) a command. It's just a directive. Directives can be polite invitations ("Come in"), suggestions ("Have a seat"), or even just good wishes ("Have a nice day!").

What is linguistics, and why do they embarrass your international customers?

In the May 28 Ecommerce Times, Naseem Javed has a "Viewpoint" article entitled "Six Questions to Spur Web Success". Question number 5 is:

5. What is linguistics, and why do they embarrass your international customers?

A site name in one country can mean something entirely different when it circumnavigates the globe. How do you tackle such language issues? The answer is to acquire skills and a deeper understanding of global communications. Even if you're a regional player, your sites are still visible and exposed to the entire world. Cyber branding is an extremely global phenomenon.

Note that "A site name in one country can mean something entirely different when it circumnavigates the globe" is, I think, an Escher sentence of a new type, though I can't quite get it to sit still long enough to be sure.

There are some other great lines in this article:

One must determine the desired size, personality and length of the name, plus the choice of alpha characters, as each emits its own unique signals.

Customers must allow a name brand to settle in their minds before they give you cash.

When trying to process millions of silly and randomly structured names, the mind becomes overly tired.

The future can be pretty clear if it is planned today.

[Thanks to David Donnell for emailing the article reference].

[Update: Margaret Marks emails a link to a critical discussion (at wordlab) of an earlier Javed column: "... we feel compelled, in the interest of our profession, to debunk this bunk point-by-point...". Read the whole thing.]

More conjectures and refutations on strict transitivity

My recent suggestions for verbs so rigidly transitive that they always have an overt direct object (where it is permitted) were have and keep. There may be some others; but not the ones some people have been sending me.

Andy Durdin was immediately reminded (as I should have been) of the words from the old Church of England marriage service from the Book of Common Prayer:

"I _______ take thee _______ to my wedded wife, to have and to hold from this day forward, for better for worse, for richer for poorer, in sickness and in health, to love and to cherish, till death us do part, according to God's holy ordinance; and thereto I plight thee my troth."

However, I think this is one of the cases where the construction involved requires a missing object. There are lots of these constructions, and in every case it is fine for the object not to be there; but it is also fine for the object of a preposition like at not to be there:

I want a wife I can love ____ for the rest of my life

I want a copy of this that I can look at ____ whenever I want.

That diamond would really be something to have ____ if you wanted to attract thieves.

This would be a useful goal to aim at ____ .

Peace of mind is a wonderful thing to have ____.

That Rembrandt is a wonderful thing to gaze at ____.

What these examples show is that in some kinds of sentence you are required to have a missing noun phrase. We're talking about whether or not you can leave it out in a context where it would normally be permitted.

That doesn't mean I was right about have. I wasn't, as email correspondents and bloggers have been jumping all over me to show. Keith Ivey sent me by email a Googled sentence, The world we live in is a world of those who have and those who don't, which seems fine. And Jonathan Mayhew offers an attested example, from Billie Holliday's "God bless the child": Mama may have, papa may have / But God bless the child that's got his own. Douglas Davidson points out that the Bible also says For he that hath, to him shall be given: and he that hath not, from him shall be taken even that which he hath, and he is quite right, it doth. Language Hat emailed me to point out that there is a book by Ernest Hemingway entitled To Have and Have Not. All in all, that pretty much does it for have.

Sasha Albertini suggested give and take might be obligatorily transitive, but I don't think so: The trouble with you is that you know how to take but you have no idea how to give.

Still, there may be some verbs that are. Adam Albright proposes a list that are about as solid as I can imagine coming up with. He doubts that an implicit objects would ever sound good with any of these verbs:

attain, attribute, cause, comport, delineate, depict, eclipse, impute, induce, portray, predecease, resemble, squelch, subsume, supercede, utter

The nice thing about this little puzzle is that it is highly empirical: you can always find one of your conjectures is blown away completely by a single counterexample. I once thought abandon was a solid case, and then I leafed through a copy of Atlantic Monthly at an airport bookstall one day in the 1990s when Newt Gingrich was threatening his Contract With America, and I read that the conservatives in the Congress were implacably devoted to the destruction of bloated Federal programs of expenditure: "Where necessary, we must not merely revise, we must abandon." I put the magazine back on the rack and got on the plane knowing that I couldn't cite abandon as strictly transitive any more. And as Adam says:

I also thought "await" might be one, but then I discovered this quote from T.H. White's "Once and Future King":

"There is nothing," said the monarch, "except the power which you pretend to seek: power to grind and power to digest, power to seek and power to find, power to await and power to claim, all power and pitilessness springing from the nape of the neck."

This is a lovely example of a genuine context in which plenty of transitive verbs could be coerced into occurring without their usual objects. And a similar case could readily be imagined that would remove several of the verbs on Adam's list above:

If you want to be an artist, it is not enough just to splosh paint around; before your abstractions can mean anything you must first study representational art — you must learn how to delineate, to portray, to impute, to depict.

I think that is convincingly grammatical (not that it's a genuine citation: sometimes a syntactician cannot Google, but must invent). As yet I am not able to see it as likely that objectless occurrences will be found for attain, attribute, cause, comport, eclipse, induce, keep, predecease, resemble, squelch, subsume, supercede, or utter. But who knows? It may merely be that I lack the necessary imagination and haven't yet spotted cases that are out there somewhere in textland waiting to be Googled up.

The great vow shift

For those of you who are planning to be in Philadelphia within the next few weeks, here's a short review (sent by Anna Papafragou to a local mailing list) of a play with a number of linguistic connections.

The Adrienne theater is now showing a play called 'Speech acts' written by

Claire Gleitman (Lila and Henry's daughter). This is a play about the

successful career and not-so-successful marriage of a female linguist. It

is a rare opportunity to see a play where the characters agonize over

giving LSA papers, academia, prescriptive grammar and the Great Vow

Shift (after all, the play is also about a troubled marriage). The play is

very funny - I saw it last night at the premiere and really enjoyed it.For those of you who would like to see it, it is on Mondays,

Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays and Friday nights, through June 18:Adrienne Theatre

2030 Sansom St.

Philadelhia

(ground floor, called "The Playroom").

Consider that 20-30 people a day visit our site to learn about wedding vowels, I'm surprised to learn that "great vow shift" is not in Google's index at the moment. Yes, I recognize that people who know what the Great Vowel Shift is also know how to spell it, but the same people tend to be fond of puns, and this is a good one.

WhG/gp and other problems of quantification

This morning I checked the web for uptake on Geoff Pullum's proposal that the measure of (document) frequency on the web should be denominated whG/gp, i.e. "web hits on Google per gigapage". I didn't find evidence of mass buy-in, though it's far too early to tell. But once I got past all the hits associated with the Werner-Heisenberg-Gymnasium Göppingen, whose domain name is "www.whg-gp.de", I did find this post by Russ Barnes at apostropher.

Russ is also worried that the British may be catching up to the U.S. in wingnuttery. I would have guessed that our U.K. cousins were way ahead, but I've never seen a quantitative study.

An ancient and fatherly show

There's been a lot of feedback on the "partitive participial relatives" that I discussed a couple of days ago. These are examples like "At present, personal injury cases are heard by many different Judges, some of whom having no experience in this field." Steve at Language Hat wrote about the topic, and his (literate and erudite) commenters commented on it, and Neque Volvere Trochum at entangledbank provided more analytic depth (as did N.V.T.'s literate and erudite commenters), and I got a bunch of email from our (l. and e.) readers. Andrew Durdin wrote in with some examples from classic texts (given below). Leaving aesthetic judgments to the side, I'll summarize the results by saying that most people seem to agree with me that the construction is ungrammatical, but some agree with Haj Ross (and the writers of the googled examples) in thinking that it's OK.

However, I wrote "seem to agree with me" because there are several different constructions being discussed, and it's possible to accept some of them while rejecting others. That's the way my own reactions fall out, for example. In my original post, I mentioned one such distinction in passing, and passed over the other in silence -- the post was already too long -- but the result was that some people misunderstood what I meant, so I'll try to clarify it here.

As before, those who are not interested in English syntax will want to turn their attention to some of our other topics, say Arabic domain names or vole as game animals.

The key question is whether a supplementary clause containing "whom" is tensed or not. If the answer is "no", then we have an example of the structure that I originally discussed. If the answer is "yes", then there are a couple of different sub-cases, to which people's reactions may also differ.

In all the cases under discussion, we have "Q of whom V-ing ..." at the start of a non-restrictive (or "supplementary") relative clause, where Q is something like some, both, most, neither, many, a few,, etc., V-ing is the present participle of a verb (usually having or being, though that is mainly because the result is an easy pattern to search for), and then ... matches the rest of the clause.

In some cases, the rest of the supplementary clause is nothing but the remainder of the verb phrase headed by the participle V-ing. That's the case with the first three examples that I gave (modulo working out the ... in the second one, where I didn't quote the original sentence in full), and it's also the case with this simple example that I cited later:

"He was one of four brothers, three of whom having died or departed."

The point is that the relative clause -- the clause containing the whom -- has no tensed (or "finite") verb.

Then there is a second structure, in which the supplementary clause is itself a complex consisting of two clauses. The first one is a participial clause, which stands as an initial supplement to a second, finite-verb clause. I gave two examples of this construction, including:

"The next evening we spent with the Consul and his two pretty daughters, neither of whom being able to speak a word of English, the conversation was carried on in French."

Finally, there is a third structure, where V-ing heads a participial relative clause serving as a supplementary modifier of the partitive Q of whom phrase, which in turn is the subject of a tensed verb following the participial relative. I didn't provide any examples of this structure, since I thought it was obvious that it isn't relevant, but of course nothing in this area is obvious. So here's a classical example, courtesy of Andrew Durdin:

(link) "[U]nder which every one did sit in his order according to his dignity, to keep him from the heat of the sun; divers of whom being of good age and gravity, did make an ancient and fatherly show." (Francis Pretty, Sir Francis Drake's Famous Voyage Round the World, originally published in 1580)

You can see the difference more clearly if we take the three supplements by themselves, replacing "whom" with "them", fixing Pretty's punctuation for clarity, and replacing his "divers" with "some" for the same reason:

(a) Three of them having died or departed.

(b) Neither of them being able to speak a word of English, the conversation was carried on in French.

(c) Some of them, being of good age and gravity, did make an ancient and fatherly show.

Example (a) is not a complete sentence, since it lacks a tensed verb, but (b) has the tensed main verb "was carried (on)", and (c) has the tensed main verb "did make".

Using square brackets for clause boundaries, and putting the participial clauses in red, we can schematize these three structures as:

(a) [ (Q of them) V-ing ... ]

(b) [ [ (Q of them) V-ing ... ] [ Subj VerbPhrase

] ]

(c) [ (Q of them) [ V-ing ...] VerbPhrase]

Now, we can take each of these structures, replace (the word) them with whom, and embed the whole thing in a main clause in which some noun phrase is to be non-restrictively modified by the structure we've created.

In the case of structure (c), the result is a completely normal if somewhat complex supplementary relative clause. Put the participial clause in parentheses, and it won't even be too hard to read:

[link] ... I am talking about 54 million people in the U.S., some of whom (being wealthy) can afford a better life ... (re-punctuated for clarity)

In the case of structure (b), the result is a non-restrictive relative clause in which the relative pronoun whom is buried inside a recursively-embedded participial supplement. This is a dangerously complex structure, but I find it perfectly grammatical, once I figure out what the writer had in mind. Such patterns seem to have been fairly common in earlier centuries, when grammatical complexity was not only tolerated but even encouraged. Of the two examples that I originally cited, I find the first to be perfectly clear, though a bit archaic-seeming, while the second is very hard to construe. Here is it again, with a comma and some parentheses added in a feeble attempt to make the writer's intent easier to see:

"In this report I have dealt more in particulars, for the reason there are no reports from brigade commanders, ( [ all three of whom having been captured ], I reserve to myself the privilege of making such corrections as would appear right and proper when I subsequently have the opportunity to examine their reports. )"

Here is the promised list of examples from Project Gutenberg e-texts, emailed by Andrew Durdin -- with my classification of each into the categories (a), (b) and (c) as defined above. Note that only category (a) is really an example of the structure that I originally intended to comment on.

"under which every one did sit in his order according to his dignity, to keep him from the heat of the sun; divers of whom being of good age and gravity, did make an ancient and fatherly show." (Francis Pretty, Sir Francis Drake's Famous Voyage Round the World, 1910; http://www.gutenberg.net/etext01/fdvrw10.txt)

{type (c)}"Sir Henry Sidney had three children, one of whom being Sir Philip Sidney, the type of a most gallant knight and perfect gentleman." (GORDON HOME, WHAT TO SEE IN ENGLAND, 1908; http://www.gutenberg.net/1/1/6/4/11642/11642-8.txt)

{type (a)}"The duke left Filippo and Giovanmaria Angelo, the latter of whom being slain by the people of Milan, the state fell to Filippo" (NICCOLO MACHIAVELLI (anonymous translation), HISTORY OF FLORENCE, 1901; http://www.gutenberg.net/etext01/hflit10.txt)

{type (b)}"the marriage register contains an entry of the names of Thomas Tilsey and Ursula Russel, the first of whom being "deofe and also dombe," it was agreed by the bishop, mayor, and other gentlemen of the town, that certain signs and actions of the bridegroom should be admitted instead of the usual words enjoined by the Protestant marriage ceremony" (The Mirror of Literature, Vol. 20, Issue 572, October 20, 1832; http://www.gutenberg.net/1/1/8/6/11863/11863-h/11863-h.htm)

{type (b)}

There is another dimension of variation -- is the embedded non-restrictive relative clause placed at the beginning of the main clause, in the middle of the main clause (following the modified noun) or at the end of the main clause (perhaps immediately after the modified noun, or perhaps following some other stuff)?

For some people, the biggest surprise is that these Q-of-whom V-ing clauses can sometimes occur sentence-initially, preceding the modified noun(s), as in the first example that I cited:

"Both of whom being influenced by Ellington, Rowles and Brown choose one Ellington tune for each of the two albums that comprise this two-CD set..."

Censorship?

You would think that movie directors would know what censorship is, but it seems that they don't. There's a new DVD player out, the RCA DRC232N, that is causing a fuss. This DVD player contains software called ClearPlay that cuts out words and scenes that would be offensive to the viewer. The user configures the DVD player according to his or her preferences in a number of categories: violence, nudity, blasphemy, and so forth. The ClearPlay company reviews films and produces an electronic annotation indicating the location of words and scenes that would offend a viewer with certain preferences. If the user of the DVD player wants to cut out certain kinds of material, he installs the annotation. The DVD player then cuts out whatever bits, according to the annotation, would not conform to the preferences set. Some people are using this system to control what their children watch. Others are using it for their own viewing, to avoid what they would find upsetting.

I would think that the movie industry would be pleased. Such a gadget provides people who are easily offended by current movies, or who are concerned with what their children watch, with an alternative to complaining about the movie industry and demanding censorship. It will probably increase sales, since people who might previously have avoided a film may now see it. In fact, the industry is outraged and is engaged in litigation over this. There is much talk in the media and on the web of "censorship". The Directors Guild of America says:

ClearPlay software edits movies to conform to ClearPlay's vision of a movie instead of letting audiences see, and judge for themselves, what writers wrote, what actors said and what directors envisioned.There's some muddled thinking going on here. This isn't censorship. The movie industry still puts out exactly what it wants to, and audiences still see what they they want to see. Everybody is free to use another DVD player, or to use this one with a configuration that suppresses nothing, or to use it without the annotation. All this software does is allow the user to choose to skip selected portions of the movie. Contrary to the DGA's claim, ClearPlay doesn't edit movies to conform to its vision - it simply tags them so that viewers can make their own decisions. Providing audiences with a choice is not censorship.

There is also an issue here of artistic integrity, though it is a bit of a stretch to characterize some movies as "art". The DGA seems to think that the director has the right to have his work viewed exactly as he intended it. There's some validity to this when a work is unique, which is why in some European countries there are now laws that prevent the alteration or wanton destruction of works of art, but here there's no question of the original being lost. The director's only right is to present his work to the viewer - he has no right to control what the viewer does with it. When you read a book, you read it as you wish. You can skip whatever you like, you can read it backwards, you can skip around, or look up selected bits in the index. You have no obligation to read the book as the author intended you to.

The DGA should should be ashamed of itself for crying wolf about censorship. Allowing people to skip bits of movies that they find offensive isn't censorship. Censorship is a very serious matter, and in much of the world is severe, as documented by organizations like Human Rights Watch. It isn't absent in the United States, as the National Coalition Against Censorship and American Civil Liberties Union will attest. It isn't a word that should be taken in vain.

May 27, 2004

Illustrating obligatory transitivity

It is generally assumed by syntacticians that some verbs are obligatorily transitive. An example of one that isn't is eat. It can be used either with a direct object (I've already eaten lunch) or without (I've already eaten). I don't mean in constructions where the object is required to be eliminated, like passives (The food wasn't all eaten) or relative clauses (the things that they eat); I mean that in construction types that allow the object to be present, if the verb is eat the object can just be left implicit. Some verbs are standardly said to be much more rigid, insisting on an overt direct object noun phrase. A syntactician might well exemplify with verbs like, say, discard, or abandon, because it would be easy to assent to the notion that sentences such as these deserve their asterisk annotations for ungrammaticality:

*The company eventually decided to discard.

*I hope your brother doesn't just abandon.

But the syntactician would be wrong.

Look at this sentence, which I came across in this article about moves to improve the standard of computer programming in the future:

They require the courage to discard and abandon, to select simplicity and transparency as design goals rather than complexity and obscure sophistication.

Perfectly grammatical. So there goes the idea that discard and abandon illustrate obligatory transitivity. It is in fact extremely hard to come up with a list of even ten transitive verbs associated with a really hard requirement that the direct object be explicit rather than implicit. Sometimes I almost begin to think there aren't really any. I believe I can still be confident about have and keep. But finding eight more wouldn't be easy.

AI and Kernighan's Law

Craig Silverstein, technology director at Google, was recently interviewed by Stephanie Olsen at CNET. The discussion got around to Artificial Intelligence, or at least Artificial Reference Librarians:

You have portrayed the ideal search engine as one resembling the intelligence of the Starship Enterprise or a world populated with intelligent search pets. Can you talk a little bit about those ideas?