April 30, 2005

Ambiguity

In reference to one of my recent posts, where the Bibliothèque Nationale de France was abbreviated as "BNF", Mike Albaugh complained that

BNF still means Backus/Naur Form to me, at first glance. (or Normal :-)

OK, me too. But in interpreting abbreviations, you've got to consider the context, as an Australian traffic court judge recently explained to the author of a clever new defense against a speeding ticket:

An early contender for the 2005 Nice Try But No Cigar award goes to Carl Ross La Riviere. Yesterday in the District Court La Riviere was avidly defending himself against a speeding charge, even though the Crown appeared to have irrefutable proof: a photo of his car travelling 56 "KPH" in a 40 "KPH" zone.

La Riviere presented the court with the National Measurement Act and Regulations to prove these initials did not mean what everyone thinks they do. His argument: K stands for Kelvin, a measurement of thermodynamic temperature; P for Poise, a measurement of viscosity; and H for Henry, which measures electric inductance.

Entertained but unmoved, Judge Megan Latham agreed the abbreviation might be illogical or incorrect, but had to be seen in context, which clearly suggested it related to a vehicle speed and meant kilometres per hour. La Riviere's sentence - a good behaviour bond - was upheld.

Mike also wondered about the relationship between plan calcul and Plankalkül,

...the names given to the French national computing initiative (circa 1966) and Konrad Zuse's proposed algorithmic language (or notation :-) (circa 1946).

When I pointed him to the entry in the French Jargon File that says there's "aucun rapport" ("no relationship"), Miked answered:

Well, that's just what they would say, isn't it? :-)

and (returning to BNF) suggested that it's

Time to revive SAFEBAGEL (Scientists Against Far-out, Extensive, Burdensome Acronyms Getting Entrenched in Language).

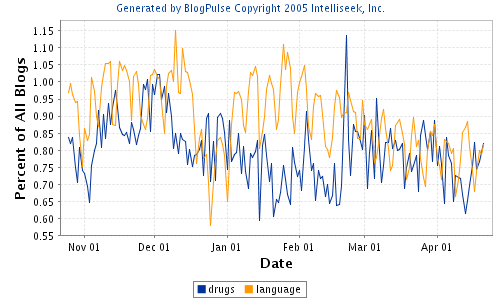

Scientists are the worst offenders. A couple of years ago, I wrote a little program to find acronyms in the MEDLINE corpus. There are lots of them -- my not-very-smart program found more than 78,000 distinct acronym/definition pairings, many of which occurred many times. Thus GM-CSF was defined 2,401 times as "granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor", but was also defined by 150 other strings. In this case, these are basically all variant forms of the same term (including a shocking number of typos -- it seems that biomedical journals are not always very well copyedited) -- see this page for the complete list of variants, each preceded by the number of times my program found it as a definition for GM-CSF in MEDLINE.

There were also plenty of acronyms whose definitions were not just different versions of the same term. For example, ABA was variously abscisic acid, Agaricus bisporus agglutinin, aminoalkyl-iodobenzamides, aminobenzamide, aminobenzanthrone, anti-biotin antibody and azobenzenearsonate. With a bit of extra context, ABA could be part of I-ABA (Iodo-4-aminobenzyl adenosine), PABA (para-aminobenzoic acid or pyridylamino butylamine), and hundreds of other things.

For most Americans, ABA is the American Bar Association. Down under, it could be the Australian Broadcasting Authority. For others, it might be the Association for Behavior Analysis or the American Board of Anesthesiology or the Antiquarian Booksellers Association. It shows my age that for me, ABA will always be first and foremost the American Basketball Association.

Life, like language, is ambiguous. Without the effect of context, referential communication would hardly ever succeed.

A tale of two media

You've probably read about or heard about Glenn Wilson's study allegedly showing that email lowers IQ more than marijuana does, and you probably even remember the amount of alleged damage (10 points) and the alleged explanation (the cognitive wear and tear of jumping around among many topics developing in parallel). Now you have a chance to read Steven Johnson's argument in the NYT Sunday Magazine that "Watching TV Makes You Smarter", and evaluate his proposed explanation:

Think of the cognitive benefits conventionally ascribed to reading: attention, patience, retention, the parsing of narrative threads. Over the last half-century, programming on TV has increased the demands it places on precisely these mental faculties. This growing complexity involves three primary elements: multiple threading, flashing arrows and social networks.

In other words, for Johnson, jumping around among many topics developing in parallel is a "cognitive benefit".

It's certainly possible that dealing with the multiple email threads linking your own social network makes you stupider, while dealing with the multiple TV-show threads linking Tony Soprano's social network makes you smarter. On the other hand, a more parsimonious explanation is available: both Glenn Wilson and Steven Johnson are blowing smoke.

Let's look at the evidence.

You probably don't remember anything about Glenn Wilson's evidence for the effects of email on IQ, except that "a study showed" it, because he hasn't presented any. Not even a sketch of how the experiment was done has appeared in any of the stories that I've read, and searching several databases of scientific information leads me to conclude that no details have so far been published anywhere at all, not even in the most obscure psychometric journal. It's possible that no details will ever be published, because this was apparently part of a study privately commissioned by HP, and its author has a history of hopping around from topic to topic himself: political psychodynamics, sex differences, love addiction, and the psychology of bubble baths, among other things.

As I suggested in the blog entry linked above, there could be lots of confounding factors in an experiment on this topic. In fact, it's not easy to see how to design an experiment on the cognitive effects of email that doesn't have serious confounds. But instead of a series of carefully-documented and well-controlled experiments, we've got a single small experiment, documented only by a press release that doesn't even sketch the experimental design, and carried out by a psychiatrist whose previous work strikes me as higher in topicality than in scientific rigor.

What about Steven Johnson's evidence that TV makes you smarter? Well, Johnson is a writer of popular science books -- his last book was a tour of neuroscience called Mind Wide Open, and the NYT piece is adapted from his forthcoming book ''Everything Bad Is Good for You: How Today's Popular Culture Is Actually Making Us Smarter.'' So he's wearing his bias on his sleeve, so to speak -- we can assume that he's looking for a good story that will sell books, not seeking the truth in a careful and dispassionate way.

Still, in contrast to Wilson's press release on email and IQ, which was basically just a guy in a metaphorical white coat pushing the media's buttons, Johnson actually presents evidence and makes an argument. His evidence and arguments are all about developments in modern culture, specifically the design of TV shows, which have been getting more complicated in specific ways that he describes. His argument about the psychological effects of these cultural changes is a pretty weak one -- basically, he just asserts that more complicated experiences must make you smarter than simpler ones do. You could make the same argument about email.

Nevertheless, Johnson does actually present some supporting evidence. The part I liked best was the way he represents the plot of TV shows, as a sort of checkerboard graph in which "the vertical axis represents the number of individual threads, and the horizontal axis is time." Here's his graph of an episode of The Sopranos:

I'm not sure whether this sort of plot graph ("plot plot"?) is Johnson's invention -- he doesn't credit it to anyone else -- but I haven't seen it used before. I'd think that graphs like this would be a natural starting point for critical study of story-telling techniques, and it's easy to think of all sorts of interesting measures to derive from them. They should apply well to TV dramas like The Sopranos, where I imagine that the writers have such displays in mind as they plan episodes and seasons, and maybe even use something like them explicitly. The notion of "thread" may be harder to define for the plots of some other genres, where more of the structure is in the evolution of individual narrative strands than in the way the strands are woven together.

Anyhow, Johnson's plot plots impressed me, but his use of them didn't. He supports his generalizations with examples, without demonstrating (other than by assertion) that the examples are typical; some of the crucial cases are what we might call "generic examples", unsupported claims about typical examples of a type; and it turns out that some of the crucial aspects of his examples are not actually exemplified in the specific cases that he presents. This is normal and reasonable for journalism, but Johnson is presenting an original argument, not reporting on someone else's scholarship.

He asserts that the complexity of TV dramas has developed in four stages, of which The Sopranos is the culmination. He describes the first two stages this way:

Draw an outline of the narrative threads in almost every ''Dragnet'' episode, and it will be a single line: from the initial crime scene, through the investigation, to the eventual cracking of the case. A typical ''Starsky and Hutch'' episode offers only the slightest variation on this linear formula: the introduction of a comic subplot that usually appears only at the tail ends of the episode ...

and he depicts the "typical" episode of Starsky and Hutch like this:

The next stage is represented by the plot of a specific Hill Street Blues episode:

I'm sure that Johnson is describing a real trend, but it bothers me that the first two stages in his claimed evolution are not supported by any specific facts at all, and the change from Hill Street to The Sopranos turns out not really to be about the number of parallel plot threads at all, but about some more subtle developments:

The total number of active threads [in "The Sopranos"] equals the multiple plots of ''Hill Street,'' but here each thread is more substantial. The show doesn't offer a clear distinction between dominant and minor plots; each story line carries its weight in the mix. The episode also displays a chordal mode of storytelling entirely absent from ''Hill Street'': a single scene in ''The Sopranos'' will often connect to three different threads at the same time, layering one plot atop another. And every single thread in this ''Sopranos'' episode builds on events from previous episodes and continues on through the rest of the season and beyond.

Again, I'm sure that there's some truth here, but I can remember plenty of examples of "chordal storytelling" and cross-episode continuity in Hill Street Blues. And I'm sure that Dragnet and Starsky and Hutch had a very different plot layout from current shows, but it'd be nice to see at least one specific example rather than an assertion about what is typical. For all four stages, it'd be even better to see an argument based on analysis of a reasonable sample of shows. Overall, this is the kind of argument from assertion that often establishes as conventional wisdom a proposition that turns out to be completely false when someone finally gets around to checking it.

I was going to start the conclusion by writing "If Johnson were a scientist...", but that's misleading. This is not about science vs. the humanities, or even about good science vs. bad science. It's about rational investigation.

Everyone these days seems to believe that modern life is complex, fragmented and disjointed, in comparison to the life of the past. And most people have some kind of opinion about the effects on our attention span, our intelligence, our culture, our politics, our morals. Given how important this is, you'd think that people would look at it in a serious way, rather than just marshalling stereotypes and counter-stereotypes in rhetorical parade.

It's unfair for me to complain so much about Steven Johnson's article. He makes a clear and interesting argument about the evolution of modern mass culture, leading to a contrarian conclusion, and he supports it with a large number of interesting examples. I wish that more contemporary literary critics did this sort of thing as well as he does.

But why didn't Johnson consider doing this kind of investigation with some scholarly (or scientific) care? Alternatively, why hasn't someone else done this, so that Johnson could base his popular book and articles on a solid foundation of fact rather than a flimsy scaffolding of anecdote and rhetoric? Oh, I know, it's because the fragmentary and disjointed nature of modern life has left us without the attention span required by scholarship and science. Or wait, I guess it's actually because the experience of modern complexity has made us smart enough to transcend the plodding path of scholarship, leaping to valid conclusions in a cyberintuitive blink. One or the other, anyhow: whatever.

[Update 9/25/2005: for the truth about the experimental design of the "email lowers IQ" studies, and an apology for blaming the media's excesses on Glen Wilson, see this post.]

April 29, 2005

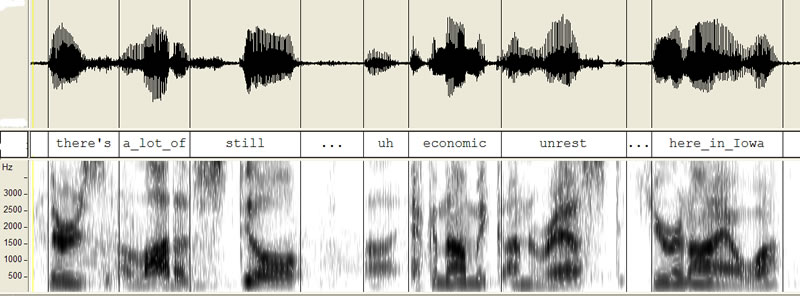

Linguistic candidate coverage

Last month on phonoloblog, Bob Kennedy commented on an LA Times story on the difficulty local voters have pronouncing LA mayoral candidate Antonio Villaraigosa's name. Last weekend, there was another story about Villaraigosa and linguistic difficulty in the Times, this time about Villaraigosa's apparent difficulties with Spanish. This article is interesting for purely sociolinguistic reasons -- like many Latinos in the U.S., Villaraigosa's Spanish was not exactly aided along during his early years, with largely predictable effects on his competence in the language -- but I wonder what effect this sort of "candidate coverage" has on the average LA voters who may read it. Will any of them judge the candidate, positively or negatively, on either of these completely irrelevant linguistic grounds?

[ Comments? ]

Crisis ≠ Danger + Opportunity

A few months ago, Mark Swofford at Pinyin.info posted Victor Mair's terrific essay debunking the "widespread public misperception ... that the Chinese word for 'crisis' is composed of elements that signify 'danger' and 'opportunity'. As a result, I can link to it, in response to an email from Robert Neal Baxter, who quotes from an article by Xavier Queipo on a Galizan news and opinion site:

Os chineses, na súa lingua de ideogramas, non teñen un ideograma específico para designar o concepto "crise" e recorren a unión de dous ideogramas, o que representa "riscos" e o que representa "oportunidade".

Chinese people, in their ideogram language, don't have a specific ideogram to refer to the concept 'crisis', resorting instead to joining together two ideograms which representing 'risks' and 'opportunity' respectively.

The cited article is of course not about Chinese at all, but about political issues in Galiza, and the author is just using this (false) linguistic cliche as a rhetorical framing device.

Robert doesn't know any Chinese, but (being well educated linguistically) he sees that nothing about this trope makes sense, and observes that

People really shouldn't just make stuff up as they go along about other peoples, cultures and languages just to suit their rhetorical or stylistic needs.

Indeed. Of course Queipo didn't make this up, in the sense of employing any creative invention. He just deployed a cliché. But someone once made this up, and people have been repeating it ever since, just like the nonsense about Eskimo snow words.

Robert continues:

What this shows, at best, is a profound misunderstanding of the way Chinese works. [...]

At worst, it reveals a journalistic willingness to exploit people's fears and ignorance about far-flung peoples with weird habits and customs and their corresponding willingness to believe any old bullshit that people make up about them. [...]

Would it be fair to assume that English has no word for what the French refer to as 'papillon', resorting instead to a compound made out of the words 'butter' and 'fly'. What would such a statement, even if it were linguistically valid - which it isn't - show about the language or the speakers of the language in question? Probably very little. In fact it's about as likely that a Chinese speakers using the word 'crisis' made up of whatever morphemes it happens to be made up of is to be aware of this secondary reading as an English speaker would be to think that butterflies are some sort of 'air-borne grease balls'.

Didn't Michel Foucault once point out that butterfly expresses a fundamental contradiction in anglophone culture: the libertarian urge to take wing, subverted by the consequences of a diet too rich in animal fat?

April 28, 2005

News flash: European national libraries are willing to take EU money

According to an AFP-based article in Deutsche Welle (4/28/2005),

In a stand against a deal struck by five of the world's top libraries and Google to digitize millions of books, 19 European libraries have agreed to back a similar European project to safeguard literature.

Nineteen European national libraries have joined forces against a planned communications revolution by Internet search giant Google to create a global virtual library, organizers said Wednesday. The 19 libraries are backing instead a multi-million euro counter-offensive by European nations to put European literature online.

The 19 signatories are "national libraries in Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Poland, Slovenia, Slovakia, Spain and Sweden". Apparently the British National Library "has given its implicit support to the move, without signing the motion" (whatever exactly that means), and Cyprus, Malta and Portugal are expected to sign up as well.

This all started with a warning a couple of months ago by Jean-Noël Jeanneney, head of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF), that Europe faces the "crushing domination of America" in the cultural arena, and an initiative by Jacques Chirac to promote Jeanneney's proposal for a pan-European publically-funded competitor to Google Print.

It's not an enormous surprise that the national libraries are in favor of "a multi-year plan" with a "generous budget" to provide for them to plan, implement and deliver this service. And I sincerely hope that this turns out to be a success, as Airbus has been, and not another "plan calcul". This was badly conceived and badly implemented Gaullist plan to promote the French computer industry, 1966-1975, discussed in context here:

From 1965 on, General de Gaulle and the government devoted their attention to developing a national computer and communication technology industry. After blocking the acquisition by a giant US firm, General Electric, of what was at the time France's only computer company, Compagnie des Machines BULL, the government decided to create the Compagnie Internationale pour l'Informatique (CII) as part of its computer development plan or "Plan Calcul" (13 April 1967). In its early years, the company would enjoy "national preference" from users in the public and semi-public sectors.

The lightning pace of development in the field of computer science, however, doomed these efforts to failure.

This concern is not mine alone: an op-ed by Bertrand Le Gendre in Le Monde of 4/21/2005, discussing the Jeanneney/Chirac initiative, is entitled "Le plan calcul de la BNF" ("The plan calcul of the BNF").

Le gaullisme était particulièrement chatouilleux sur ce chapitre de la grandeur et longtemps il a fait illusion : paquebot France, supersonique Concorde, plan calcul. Trois fiertés nationales, trois gouffres financiers, trois échecs commerciaux, qui incitent à se demander si ce"Google à la française" dont la Bibliothèque nationale de France (BNF) serait le pivot n'est pas, lui aussi, un pari risqué.

Gaullisme was especially ticklish about this business of grandeur, and has had a long history of delusion: the ocean liner France, the supersonic Concorde, the plan calcul. Three objects of national pride, three financial sinkholes, three commercial failures, which lead us to ask whether this "Google French style" based on the BNF is not, also, a risky bet.

I see little reason to be confident that the 20-odd national libraries will be able to work together efficiently to plan and implement this massive digitization process, and to make the results available to the public in an effective way. There is likely to be a substantial communications overhead, and perhaps some issues of local technical competence. Of course, Europe has many highly skilled technical managers who could make a success of such a project, but I wonder if the politics of the situation will allow any of them to be given the opportunity to do it.

[Deutsche Welle reference via email from Benjamin Zimmer]

Other current stories: in Le Monde, the Inquirer (where the likely cost is underestimated by an order of magnitude), from the AFP wire in the Sydney Morning Herald, and (a generally-negative opinion piece on the Jeanneney/Chirac initiative as a whole, by Pierre Buhler from Sciences-Po in Paris) in the IHT.

From the Le Monde article:

Pour M. Jeanneney, il n'est pas question de laisser les politiques se mêler directement des contenus. Des conseils scientifiques européens, composés de bibliothécaires, de conservateurs, d'informaticiens et de savants de toute nature, pourvoiraient à les définir. Une instance qui en serait l'émanation déterminerait une stratégie collective. Elle "s'attacherait à encourager tous les choix privilégiant la mémoire des échanges d'une nation à l'autre." Et devrait répondre "à cette inquiétude lancinante du n'importe quoi, de la dispersion du savoir en poudre" , caractéristique à ses yeux du projet Google, "dont le président des bibliothèques américaines - Michael Gorman - s'est fait le dénonciateur persuasif et inquiet."

For M. Jeanneney, it's not a question of letting the politicians meddle directly in the content. European scientific councils, made up of librarians, conservators, computer scientists and scholars of all kinds, will arrange to define it. A decision-making body that would result from this process would decide on a collective strategy. This body "would dedicate itself to encouraging all options, favoring the retention of the exchanges between one nation and another." And it should respond "to that throbbing anxiety for anything and everything, scattering knowledge like dust", characteristic in his view of Google's project, "which the president of American libraries" -- Michael Gorman -- "has so persuasively and disturbingly denounced".

Reste un risque majeur : face à la souplesse et à la détermination d'une entreprise privée, disposant de moyens financiers très importants, l'Europe risque d'opposer à la firme californienne une complexe usine à gaz, addition d'administrations atomisées, jalouses et paralysées par des interférences politiques.

There remains a major risk: in contrast to the flexibility and determination of a private enterprise, able to spend large sums, Europe risks opposing to the California firm a gasworks project, adding atomised bureaucracies, paralyzed by administrative jealousies and political interference.

Previous Language Log coverage of this story:

2/01/2005

Revenge of the Codex People [a roundup of Gorman links]

2/20/2005 Google challenges Europe?

3/08/2005 The Progress and Prospects of the Digital BNF

3/19/2005 France challenges Google

3/23/2005 EuGoogle advances

3/26/2005 Europe's Response to Google to be Managed by ... Microsoft?

3/27/2005 Tomorrow was Yesterday

Replyese, or everyday English?

I recently had the following exchanges with technical staff at Stanford. The first relevant message went as follows (I suppress irrelevant details):

From: A...

Date: April 27, 2005...

To: zwicky@Turing.Stanford.EDU (Arnold Zwicky)

Subject: Re:...

In soc.motss, you wrote...

I forwarded a copy of A's message to B, who replied, in part:

I can't tell from below who the "you" is who wrote something in soc.motss, but perhaps it's *you*.

B can't tell who the "you" is? What's going on here?

My hypothesis is that B is treating e-mail as an instance of a special register of English, Replyese, while A and I are reading it as an exchange in everyday English, supplemented by a variety of extra information (like times in GMT). In particular, A and I think that since A was writing to me -- a fact made clear by the "From:" and "To:" headers -- the pronoun "you" refers to me, just as it would in a note to me or a phone call to me. B, on the other hand, expects (I surmise) that persons will be identified by their full names (and e-addresses) in the body of the message; the headers are irrelevant. B was expecting A to have written something like:

In soc.motss, Arnold M. Zwicky (zwicky@Turing.Stanford.EDU) wrote...

Or perhaps:

In soc.motss, Zwicky, Arnold M. (zwicky@Turing.Stanford.EDU) wrote...

Or:

In soc.motss, Woolly Mammoth (zwicky@Turing.Stanford.EDU) wrote...

Or simply:

In soc.motss, (zwicky@Turing.Stanford.EDU) wrote...

In everyday English, such a use of proper names, nicknames/pseudonyms, or addresses would be just bizarre. If Dan Jurafsky, say, greeted me in the halls of Language Log Plaza by saying "In soc.motss, Arnold M. Zwicky (zwicky@Turing.Stanford.EDU) wrote..." or any of the other variants above, I would be seriously concerned about his mental state.

I suppose A and I, clinging in our quaint way to the conventions of two-person interchanges, even in e-mail, are hopelessly Out of It. Oh, I mean that I suppose A (supply.e-address.here) and Arnold M. Zwicky (Turing.Stanford.EDU) are hopelessly Out of It.

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

Voilá: the movie

To explain the fractured syntax of a New Yorker Infiniti ad, I invented an elaborate plot sequence, despite having no relevant knowledge or experience of the advertising business. Then I came across some misspelled French decorating a wine ad in the same magazine, and concluded (with equal ignorance) that the responsible parties are probably just incompetent and careless. Now Ed Keer, a linguist working as an advertising copywriter, sets me straight by supplying a believable plot for the wine ad blooper.

Having now been on the inside of an agency, I can tell you how this went down. The copywriter most likely made a mistake and wrote

violávoilá in the manuscript. Then the sharp-eyed editor noticed the problem and changed it toviolàvoilà. All was fine until it went to the client for review. The client remembered back to her highschool French and changed it back toviolávoilá. The editor at the agency flew into a rage. The account person asked if the client is right. The editor composed a heated email explaining the problem, complete with scanned dictionary and style book pages. The account person gently tried to explain the problem to the client. By this time the client had found a few colleagues to back her up. The writer, exhausted from coming up with 50 different concepts to sell cheap wine, ignored the whole thing. At some point after that, the account person uttered the phrase, "We're not going to die on our sword for this." And so it went to print.

That makes sense. I can see Bill Murray as the copywriter, Melanie Griffith as the client, and John Lithgow as the editor. Maybe the copywriter and the client are former lovers... and you can make up the rest for yourself.

I should know better than to ascribe to simple human error something that could instead be explained on the basis of a complex network of ignorance, interpersonal conflict, defensiveness and communications failure :-).

Standing out by blending in

(Annals of post-modern advertising, part 3.) Nissan North America bought another two-page spread in the front of the May 2 New Yorker, as they did in the April 25 issue. This time the featured model is the Infiniti FX rather than the Infiniti M, and there are no incoherent sentences in the ad copy. Well, there are no syntactically incoherent sentences, anyhow.

The background is black, as before, with a picture of the featured vehicle on the right-hand page. At first I thought that the left-hand page was solid black, but then I realized that there are some large letters in a slightly lighter shade, roughly like this:

| if you are not generic and ordinary and homogenized you stand out no matter how similar your surroundings |

(If you have trouble reading it, try highlighting the text.)

Perhaps Saul Gorn's Compendium of Rarely Used Cliches and Self-Annihilating Sentences should be expanded to include a section on "Self-Refuting Advertisements".

It's easy to trace the associative process that produced this ad. The TV advertising for the Infiniti FX includes the catchphrase "The only thing it won't do is blend in", and the slogan on the FX website is

You've never seen anything like it.

Then you see nothing else.

(Or maybe "nothing at all"...)

So the theme is "standing out"; but people who buy luxury cars want to be fashionable as well as admirable; so they need a countervailing theme of fitting in, though of course not by being in any way ordinary or generic or homogenized. Perhaps someone at TBWA\Chiat\Day decided to embody the contradiction typographically. Then again, maybe they were just flailing around with associated concepts, and thought that black letters almost blending in on a black page would be a cool way to make a point about the Infiniti FX not blending in on the street.

Either way, it's not making me want to buy an Infiniti. Not that I'm in their target demographic anyhow.

April 27, 2005

Bad translation?

I just heard a brief interview with French author Frederic Beigbeder and the translator, Frank Wynne, of Beigbeder's novel about 9/11 Windows on the World on BBC World Service. The novel was recently announced as having won the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize. The author and translator -- who hadn't met until now, having collaborated entirely by phone and e-mail -- will split the £10,000 prize equally. When asked what it was like working with a translator, Beigbeder -- whose English was excellent -- said: "I speak very bad English, but I can read Frank's work." For a second there, I wondered whether Wynne was being praised or panned.

[ Comments? ]

"This was a total embellishment"

It's not just copywriters. Graphic designers could use a bit of fundamental education in linguistics, too. Mark Swofford at Pinyin News takes a swipe at Chris Calori and David Vanden-Eynden, for the quotes attributed to them in an April 12 article in Metropolis Magazine, under the headline Graphics That Bridge a Linguistic Divide.

It's not just copywriters. Graphic designers could use a bit of fundamental education in linguistics, too. Mark Swofford at Pinyin News takes a swipe at Chris Calori and David Vanden-Eynden, for the quotes attributed to them in an April 12 article in Metropolis Magazine, under the headline Graphics That Bridge a Linguistic Divide.

I'll refer you to Mark's post for the critique, and here just let Calori and Vanden-Eynden misspeak for themselves. First, their take on Chinese characters as "ideas":

The Chinese language has more than twenty thousand characters in common usage, and they function in fundamentally different ways than Western letters. “Each character is really an idea,” Calori says. “They’re called ideograms. The Chinese can say in four characters what it might take us a paragraph to describe.”

Then the really fun part, their analysis of the Chinese text of the sign whose design they're explaining (苏州国际博览中心 Sūzhōu guójì bólǎn zhōngxīn = “Suzhou International Exposition Centre”). I especially like the part (at the end) about how "this was a total embellishment" and "they wanted the warm, fuzzy heart center, as opposed to the cold, hard center of hell".

“Historically, Suzhou was known for its gardens and greenery,” Vanden-Eynden says. “So the top particle of the first character means ‘grass.’ The second character translates roughly to ‘green state.’

“The next two characters combine to create International. The third character stands for ‘nation;’ the big box around it is ‘mouth’ or ‘center.’ The strokes inside of the box denote ‘jade,’ which is highly prized. The fourth character represents ‘border’--but one part also symbolizes ‘the ear,’ another part ‘to demonstrate.’ So, literally translated, you’re demonstrating that you’re the prize or the center or the mouth.

“How do you describe an Expo? It’s a notion. We shortened it, because ‘exposition’ was too damn long. So what takes place at an expo? Well, a bunch of people and companies get together in one spot to show each other new products and ideas. That’s a lot to describe in one word. The Chinese manage to do it in two characters, which stand for ‘abundant’ and ‘view.’ The top part of the fifth character is ‘noting like it’ or ‘of itself’ (the cross doesn’t have a lot of significance); the second part means ‘subsidiary,’ and the bottom is the unit name for the Chinese inch, which implies a multitude of something. The sixth character is ‘to look’ or ‘view.’ So, an abundant-amount-of-things-to-look at equals expo.”

“The last two characters for Centre--it’s interesting they went with the British spelling--are actually redundant,” Calori says. “Often you see the seventh character--it means ‘middle’--for center. But the client also added the eighth character, which is the symbol of ‘heart.’ The heart is the middle, so they reinforce each other. This was a total embellishment.” Adds Vanden-Eynden: “They wanted the warm, fuzzy heart center, as opposed to the cold, hard center of hell.”

There are more than a few grains of truth in there, but they're embedded in a dense matrix of confusion. I can't resist quoting Mark's comment on the "total embellishment" of the "warm, fuzzy heart center":

This is so wrongheaded and absurd it’s hard to know whether to laugh or cry. The client didn’t add the eighth character (心). It’s used in writing the word for “center,” which is zhōngxīn (中心). The only thing “fuzzy” here is the thinking behind this nonsense.

Bad ads

A couple of days ago, I went into a long song-and-dance to explain the grammatical incoherence of an ad for the Infiniti M on pages 2 and 3 of the April 25 New Yorker. Two sentences, 29 words, $200k to run it, and the second sentence is not English. Not informal English, not dialectal English, just what looks like a careless editing error.

I made up a whole one-act-play's-worth of backstory about this, driven by the assumption that everyone involved was competent and careful. Class anxiety, clash of egos, high drama. But now I'm starting to think I was wrong. Maybe advertising copywriters are just ignorant and careless.

The inside of the back cover of the same issue of the New Yorker is an ad for Turning Leaf Vineyards. More black background, here the night-time wall of a McMansion. Warm orange window in the middle, with gauze curtains outlining the shape of a wine bottle. Behind the gauze, the silhouettes of a man and woman at dinner. He's pouring the wine, she's using chopsticks to serve the Chinese take-out. The copy is again in off-white letters, this time in a quiet space in the lower right:

An empty refrigerator

turns into a great excuseFine china and silver

make a surprise appearanceAnd voilá, Kung Pao chicken

becomes Le Kung Pao chicken

OK, no surprise for a New Yorker ad, there's more class anxiety here. Turning Leaf is Gallo's middlebrow brand, aiming for a higher level of snob appeal while staying in contact with everyday life. Adding a French definite article to "Kung Pao chicken" is a fine poetic emblem for that striving. And using an acute accent (voilá) instead of the correct grave accent (voilà) is a poignant, pathetic reminder of the potential for humiliation that social climbers expose themselves to.

Was this some copywriter's ironic subversion of the campaign's message, crystallized in one subtle little diacritical error? I doubt it. My money is on the theory that no one associated with the campaign knows any better. If the agency or the client has anyone literate in French, they weren't paying attention.

Now, I'll freely admit that I'm a careless typist, an occasional misspeller, and the world's worst proofreader. Geoff Pullum deserves course relief from Santa Cruz for all the time he puts into correcting my posts. But if I were spending $100,000 to put a full-page ad onto the back page of the New Yorker, with 26 total words of copy, I think I could manage to check the spelling.

April 26, 2005

Amaz-ing

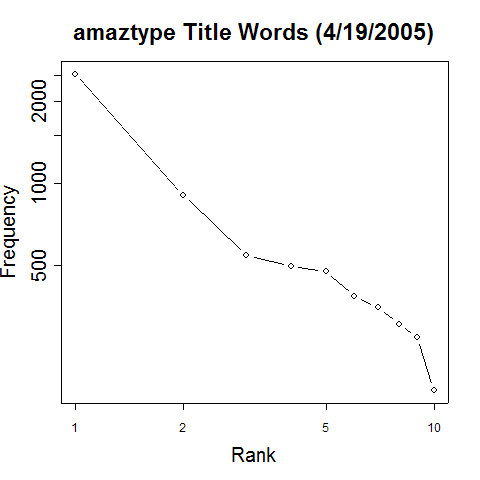

Apparently in response to my April 19th joke, the top ten listing on amaztype™ zeitgeist, in the TITLE in ALL MEDIA category, is now (Apr 26, 2005, 22:10:00 GMT)

| 1 | LINGUISTICS | 2889 hits |

| 2 | SEX | 2559 hits |

| 3 | LANGUAGE | 1442 hits |

| 4 | FUCK | 1148 hits |

| 5 | TOM HANKS | 883 hits |

| 6 | FLASH | 482 hits |

| 7 | PORN | 442 hits |

| 8 | BOOBS | 393 hits |

| 9 | LOVE | 379 hits |

| 10 | HARRY POTTER | 351 hits |

Even more amaz-ingly, the top ten in the AUTHOR in BOOKS category:

| 1 | YUGO | 1444 hits |

| 2 | LEONARD TALMY | 591 hits |

| 3 | MARK LIBERMAN | 434 hits |

| 4 | NEIL GAIMAN | 327 hits |

| 5 | STEPHEN KING | 262 hits |

| 6 | ARNOLD ZWICKY | 249 hits |

| 7 | MERCEDES LACKEY | 160 hits |

| 8 | ILLIAD | 135 hits |

| 9 | SCOTT MCCLOUD | 127 hits |

| 10 | PICKOVER | 351 hits |

So who is this "Yugo"? Searching Amazon for "Yugo" in the Author field turns up, in order, Nuclear Reactor Safety Heat Transfer, by Dubrovnik, Yugo Summer School on Nuclear Reactor Safety; El triunfo de la gracia sobre el pecado, by Pedro Yugo Santacruz; The recycling of plastic wastes in packaging, by Yugo Suzuki; Semeynyye obryady i verovaniya karel, by Yugo Yul'yevich Surkhasko; and Hokkaido no shizenshi: Hyoki no shinrin o tabisuru, by Yugo Yul'yevich Surkhasko. Perhaps there's a signal there...

Anyhow, once past that obscure and perhaps-coded reference to "Yugo", there's Len Talmy! Go Len! I'm honored to be on a list with him, not to speak of Stephen King, Mercedes Lackey, Illiad and Scott McCloud.

Here's a short Illiad sequence with a lexicographical theme:

And here's Scott McCloud's site.

But I wonder why Patrick Farley isn't on the list? Or Rob Balder:

Language and gender: the cartoon version

Simon Baron Cohen has been promoting the idea that autism is a symptom of an "extreme male brain" -- runaway male-associated systematic and analytic thought with associated deficits in female-associated social and empathetic processing. It makes me nervous when a scientific theory lines up so nicely with current cultural stereotypes. An earlier Language Log post featured Marcel Just's alternative idea -- that autism is lack of neurological coordination. And a year ago, I discussed some examples of the problems that come up when scientific research engages gender stereotypes about language use.

Today, we'll look at some cartoon versions of these ideas.

Yesterday, Tank McNamara got his first lesson in the International Women's Code:

...and today he verified the translation:

A couple of weeks ago, Sara Toomey demonstrated Jeremy Duncan's social and interactive cluelessness (from Zits):

Finally, Deadlock. This is a wonderful account of dating as game theory, by Dan Zettwoch. It which was previously discussed on Language Log 11/24/2003, but deserves to be linked again.

There are hundreds of similar examples out there -- 10-20% of all Cathy strips, for a start. For example, this year's Cathy series on income tax preparation (an annual feature) began on April 3 with a strip about gender styles

and ended on April 16 with another one:

With so much evidence to support them, how could these ideas be wrong?

Strange bookfellows

Q: What do Geoff Pullum and Emily Dickinson have in common?

A: They are the only two authors in whose works the phrase gratuitous capitalization is currently identified by amazon.com as "statistically improbable".

Let me re-phrase that, with the help of amazon's "learn more" pop-up for "Statistically Improbable Phrases (SIPs)":

Amazon.com's Statistically Improbable Phrases, or "SIPs", are the most distinctive phrases in the text of books in the Search Inside! program. To identify SIPs, our computers scan the text of all books in Search Inside. If they find a phrase that occurs a large number of times in a particular book relative to all Search Inside books, that phrase is a SIP in that book.

SIPs are not necessarily improbable within a particular book, but they are improbable relative to all books in Search Inside. For example, most SIPs for a book on taxes are tax related. But because we display SIPs in order of their improbability score, the first SIPs will be on tax topics that this book mentions more often than other tax books. For works of fiction, SIPs tend to be distinctive word combinations that often hint at important plot elements.

Click on a SIP to view a list of books in which the phrase occurs. You can also view a list of references to the phrase in each book. Learn more about the phrase by clicking on the A9.com search link.

But the funny thing is, "gratuitous capitalization" only occurs once in Geoff Pullum's The Great Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax and Other Irreverent Essays on the Study of Language, and once in The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson. So can it really be true that this is a phrase that "occurs a large number of times in [those] particular [books] relative to all Search Inside books"?

It seems misleading, in ordinary language terms, to say that once is "a large number of times".

Nevertheless, there can be a plausible argument for characterizing a phrase that occurs only once -- or perhaps never occurs at all -- as more or less "statistically improbable". This is a point that Noam Chomsky got wrong in 1957, but it's a commonplace idea by now.

It's ironic that Geoff -- the author of the Once-is-Cool-Twice-is-Queer (OICTIQ) principle for linguists and philologists -- is tagged by amazon for a "statistically improbable phrase" that he used only once. All the same, this might be a feature of the SIP algorithm rather than a bug. In an earlier post, I asked "how many times does a word or phrase need to be repeated in order to seem characteristic of a speaker or author?" and answered "not very many times, maybe only once or twice, if the use in context is salient enough".

This might be such a case -- it must be admitted that the phrase gratuitous capitalization does, as amazon puts it, "hint at important plot elements" in Geoff's oeuvre.

Still, I'd like to know more about the algorithm that amazon is using. As I observed in the previously-cited post

Simple ratios of observed frequencies to general expectations will not work..., because ... such tests will pick out far too many words and phrases whose expected frequency over the span of text in question is nearly zero.

This is an instance of the problem that troubled Noam Chomsky in 1957. There are many, many two-word sequences in Geoff's book that do not occur at all in the other works indexed so far by amazon's "search inside" program. Looking at the context in which gratuitous capitalization occurs in Geoff's book, the immediately following sentence is

The harsh yoke of (e.g.) Academic Press and MIT Press copy-editing practices imposes on authors pointless and information-destructive capitalization of `significant' words (roughly, words that belong to the categories, N, A, or V) in titles.

Choosing at random, I find (by searching on A9.com) that the sequence "authors pointless" occurs in no other work known to amazon.com (check the returns for books, not the results borrowed from Google...). So why is "authors pointless" not in the SIP list for The Great Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax? Amazon must be doing something clever.

Ah, you may say, but "gratuitous capitalization" is a syntactically and semantically meaningful unit, while "authors pointless" is not. This is certainly an issue for such algorithms -- SIPs ought to be meaningful phrases of some sort, not just random uncommon word sequences. However, it's not obvious that amazon's cleverness is based on this sort of linguistic analysis of the content of the books indexed. Take a look at the actual occurrence of "gratuitous capitalization" in The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson (pages x-xi of the Front Matter, written by the editor Thomas H. Johnson):

I have silently corrected obvious misspelling (witheld, visiter, etc.) and misplaced apostrophes (does'nt). Punctuation and capitalization remain unaltered. Dickinson used dashes as a musical device, and though some may be elongated end stops, any "correction" would be gratuitous. Capitalization, though often capricious, is likewise untouched. [emphasis added]

So in this case the "statistically improbable phrase" is no phrase at all, but a word sequence spanning a sentence boundary.

On the other hand, looking over some longer lists of Statistically Improbable Phrases, it does seem that they are limited to things that are plausibly phrases to start with. (See for example the SIP list for Ray Jackendoff's Foundations of Language.)

So here's what seems to be going on:

- amazon is indexing books by a method that throws away all punctuation, case (and stop words?), and identifying possible SIPs by reference to (2- and 3-element?) subsequences of the resulting degraded strings;

- amazon is limiting SIPs to things that are plausibly phrases in a linguistic sense, as they might occur in undegraded text, independent of their context of occurrence in any particular work -- or they are imposing some other condition that has this effect;

- candidate SIPs (identified as in [1], and limited as in [2]) are accepted iff their probability (estimated from a model derived from all books indexed) is below some threshold (and perhaps if some other conditions are met).

I'm pretty sure about [1] and [3] (though I'd like to know more about the probability estimation method, and any other conditions that may be used). [2] is the part that is least clear to me. All the methods that occur to me will either miss genuinely characteristic phrases (problems with "recall"), or flag sequences that should not be considered phrases at all (problems with "precision").

A few minutes of poking around turned up plenty of other mistakes like the Emily Dickinson one, where a SIP is not actually being used as a phrase in the cited context, but no examples at all where a SIP might not plausibly be a meaningful phrase in some context. Thus amazon must be tuning its algorithm (sensibly) for high precision at low(er) recall. But I'd still like to know how it works.

And I'm distressed to learn that Geoff and Emily are not really textual siblings after all.

April 25, 2005

And the answer is: abemus

Never in the history of blogging was a post so rapidly and decisively refuted and crushed as my profoundly ignorant remark on Cardinal Estevez's h-less pronunciation of habemus papam. The best defense that could be offered is that my post was partially right: the language is called Latin, it does have a verb habere, and papa (accusative form papam) does mean "pope". But the accurate content of my post mostly stops there. A number correspondents with more knowledge of Latin than I will ever have (I who failed high school Latin at the age of 16 and never got much better at it than I was then) wrote lengthy emails to correct me.

Eliah Hecht happened to have just been reading the book I should have looked at (if the library had been open, or if I had owned the book): W. Sidney Allen's wonderful Vox Latina. And it reports that /h/ had started to disappear by end of the Roman republic, as various omissions and misapplications show (you get ORATIA for HORATIA, AUET for HAUET, and so on); Allen says that "by the classical period in fact knowledge of where to pronounce an h had become a privilege of the educated classes." The educated Roman classes, that is.

Geoff Nathan confirms this: the /h/ was gone in Latin by the third century CE or so, and the Appendix Probi (a third-fourth century prescriptive spelling manual for Latin) has corrections that put h's back in, a key sign that the sound had all but disappeared.

But we're not half done with how wrong I was. Nathan Vaillette points out to me that

if Cardinal Estevez was not speaking flawless *Classical* Latin, you still can't complain about his *Ecclesiastical* Latin pronunciation. This norm seems to be (semi)standardized and established. For instance, the following page on the Global Catholic Network site ("adapted from the Liber Usalis [sic], one of the former chant books for Mass and Office") tells us not to pronounce orthographic "h":

http://www.ewtn.com/expert/answers/ecclesiastical_latin.htm

I found several choral sites with similar recommendations for singing church Latin, e.g.

http://www.metrosingers.org/latin.html

(I also seem to remember that John F. Collins' popular Primer of Ecclesiastical Latin says the same about "h", but I don't have it in front of me.)

Furthermore, if indeed Estevez spoke Latin with "a Chilean Spanish accent you could cut with a knife", you would expect the [b] in "habemus" to come out as a voiced bilabial fricative. And I'm pretty sure Chilean Spanish is among the "s" aspirating varieties, where [s] in some environments—syllable codas at least—is either replaced by [h] or lost completely. So unless you heard [aBemuh papam], where [B] = voiced bilabial fricative, I think you're being a tad harsh.

That last point is so obvious that I actually knew the facts, but forgot to apply them. He did indeed have a [b] between vowels, not a bilabial fricative [β]. I'm writhing on the floor with humiliation here.

There is more. John Cowan writes to point out that the Cardinal was almost certainly likely to be using

the standard pronunciation of ecclesiastical Latin ("c" and "g" as in Italian, vowel length lost, etc.). In that tradition, written "h" is not pronounced except intervocalically, where it is pronounced /k/; thus mihi is ['miki].

We see an example of /h/ > /k/ in the name of the letter "h": /'aha/ > /'aka/ > OF /atS@/ > ME > ModE /eitS/. Some people supply an unhistorical /h/ at the beginning to make it /heitS/; this is often heard in Ireland, and it's said that terrorists on both sides have used this feature to separate h-ful Catholics from h-less Protestants.

The English names of the letters, because they have never had a standard written orthography, are a juicy example of "pure" sound-change and analogy at work; they were apparently invented by the Etruscans (an Etruscan?) and borrowed into Latin, and tracing them tells us both the Latin > Old French and the ME > ModE sound changes as well as the history of the modern Latin alphabet!

John McChesney-Young has written with more details (I am too exhausted to repeat them), citing another important book that I was too slothful to get up out of my reclining chair to go and check, Sturtevant's Pronunciation of Greek and Latin (see pp. 155-157). And Bob Kennedy writes from Santa Barbara's Institute for Social, Behavioral and Economic Research to provide additional evidence of vacillation with [h-] in Classical Latin:

A poem by Catullus mocks someone who hypercorrectively inserts [h] at the starts of vowel-initial words. The man in the poem is named Arrius, and "hinsidiously" insists on referring to Ionia as Hionia.

There is a discussion at http://community.middlebury.edu/~harris/Texts/catullus3.html, which includes this:

The Romans had trouble with the initial aspirate / h /, which they sometimes omitted, other times produced without reason. The wide prevalance of Romans as soldiers and adminsitrators in the Greek speaking world may account for the fact that the Greek grammarians of Alexandria felt it necessary to introduce the "smooth and rough breathing" marks at the start of Greek words which have an initial vowel. Everyone in a decent position at Rome had to know Greek, but this Latin Cockneyism would still be a problem for men like Arrius when they tried with difficulty to talk in public.

This morning in Language Log Plaza little knots of staff writers were talking to each other in low voices and then breaking off when I came by. Now when I go into our ground-floor coffee shop, the Latté Linguistica, people get theirs to go so that they won't have to talk to me; they rush off, or pretend to be looking down into their coffee cup as if they thought they'd seen a bug floating in it... I'm being ostracized. I made a remark on Language Log without doing my fact-checking. I am the lowest form of linguistic slime. I am no better than a BBC science reporter.

I am probably not going to be here very much longer. The call will come to present myself in the Big Office where MYL sits, and after a brief and painful talking-to I will be introduced to the security guard who will help me carry the things from my desk to the front door. Then they will shut down my email account and scrub the hard disk on my desktop machine in preparation for handing it to the new staffer who will replace me.

Which, on the bright side, will at least save me from having to answer quite a lot of email. It occurs to me that there are about a billion Catholics, and so far I have only heard from two or three of them.

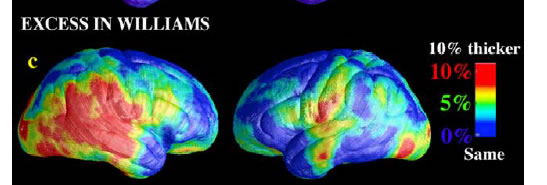

News about brain structure in Williams Syndrome

In the latest Journal of Neuroscience, there's an interesting paper about

brain structure in Williams Syndrome, a disorder caused by deletions of variable length in a gene on chromosome 7 (7q11.23) that codes for the connective-tissue protein elastin, and perhaps in other

adjacent genes. Among the many symptoms of the syndrome are mental redardation with hypersociability, relatively spared language, and relatively spared musical abilities that sometimes rise to savant levels. What's new in this paper is a systematic and thoughtful examination of differences in brain structure between WS subjects and controls.

In the latest Journal of Neuroscience, there's an interesting paper about

brain structure in Williams Syndrome, a disorder caused by deletions of variable length in a gene on chromosome 7 (7q11.23) that codes for the connective-tissue protein elastin, and perhaps in other

adjacent genes. Among the many symptoms of the syndrome are mental redardation with hypersociability, relatively spared language, and relatively spared musical abilities that sometimes rise to savant levels. What's new in this paper is a systematic and thoughtful examination of differences in brain structure between WS subjects and controls.

The reference is Thompson PM, Lee AD, Dutton RA, Geaga JA, Hayashi KM, Eckert MA, Bellugi U, Galaburda AM, Korenberg JR, Mills DL, Toga AW, Reiss AL. "Abnormal Cortical Complexity and Thickness Profiles Mapped in Williams Syndrome." Journal of Neuroscience, 25(16):4146-4158, April 20, 2005.

The background finding (in keeping with earlier studies) is one of general reduction in brain size, and especially in "white matter" (i.e. neuronal interconnections consisting of myelinated nerve fibers, as opposed to "grey matter", consisting mainly of cell bodies):

...the WS group had greatly reduced overall brain volumes (...left and right hemisphere volumes were reduced by 13.3 and 12.2%, respectively)...

... this overall deficit was attributable to primarily a far more dramatic reduction in white matter (left hemisphere, -18.0%...; right hemisphere, -18.3% ...) than gray matter, although gray matter also was reduced severely (left hemisphere, -6.8%...; right hemisphere, -6.2%...).

[The] WM deficit was found somewhat uniformly across all lobes (frontal, -15.9%; parietal, -18.4%; temporal, -21.2%; occipital, -20.0%...). Lobar GM volumes also appeared uniformly reduced (frontal, -5.9%; parietal, -7.4%; temporal, -5.3%; occipital, -8.6%).

However, against this background, there were striking local exceptions:

The WS group had greatly increased cortical thickness in a large neuroanatomical region encompassing the perisylvian language-related cortex. This region surrounds the posterior limit of the Sylvian fissures and extends inferiorly into the lateral temporal lobes (Figure 4c, red colors denote a 10% thickening of the cortex relative to controls). The region of significant thickness increases also extended over the inferior surface of the right temporal lobe (Fig. 4e) into the collateral and entorhinal cortex. This region included the fusiform face area, which processes facial stimuli, a cognitive ability in which WS subjects show notable strengths.

Here's the picture from their Figure 4c:

The authors also

...developed an algorithm to measure the fractal dimension, or complexity, of the human cerebral cortex, based on a previous algorithm that we developed for mapping the complexity of deep sulcal surfaces in the brain (Thompson et al., 1996).

According to this measure,

Cortical complexity was ... significantly increased in WS for both brain hemispheres.

The differences were small (e.g. left hemisphere Williams 2.2522 +/- 0.0016 SE, left hemisphere controls 2.2457 +/- 0.0014) but significant (p < 0.00145; two-tailed t test in this case). The authors comment that

Although these differences appear to be small in magnitude (~0.1– 0.3%), this can be misleading because they are computed from a log–log plot, in which small differences in slope translate into very large differences in gyral complexity.

As their plot shows, there is a great deal of overlap in the values for individual subjects:

Their discussion of function interpretations is interesting:

One simplistic interpretation is that thicker cortex is better, and that regionally thicker language cortex in WS subjects may account for their verbal strengths and unusually expressive language. By a similar argument, WS subjects are also prone to seek the gaze of others (Mervis et al., 2003), and the thicker cortical region in WS also encompasses the superior temporal sulcus, an area important in face and gaze processing (Kanwisher et al., 1997; Zeineh et al., 2003). However, this interpretation is unduly simplistic for several reasons. First, WS subjects have relatively intact language, but they do not outperform controls, which would be implied by the idea that thicker cortex is better (Haier et al., 2004). Second, WS subjects do not have enhanced function in other systems with thicker cortex (e.g., posterior and lateral occipital and inferior occipital-temporal regions), which subserve visuospatial functions impaired in WS. Third, a similar thickening of perisylvian cortex in fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) (Sowell et al., 2002b) is not associated with better language function.

They add that

In both WS and FAS, excess cortical gray matter is most likely a result of a failure of cortical formation during gyrogenesis or a concomitant failure or delay in myelination, perhaps specifically in subcortical U-fibers (conventional MRI cannot distinguish these two possibilities).

In thinking about genetically-related brain structure/function correlations, I always wonder how much of such patterns is genetically determined in an open-loop sort of way, and how much depends on developmental processes that involve feedback from experience (which might amplify initial differences in ability, interest and motivation). So I was very happy to see the authors explicitly raise those issues:

Cortical architecture in WS is likely influenced by haploinsufficiency for specific deleted genes, but it is also dynamic and environmentally influenced throughout life. This study correlates genetic mutation and anatomical change, but causality cannot be determined. There is no way to make any simple categorical interpretation of genetic and nongenetic influences, because these cannot be disentangled, and both may occur downstream of a genetic lesion. The observed cortical thinning may be shaped primarily by negative genetic influences (that impair parietaloccipital structure and function). Nonetheless, the cortical increases may represent increased use or overuse of specific networks. Even if the thickening represents an adaptive response to the genetic deletion, whether or not it is functionally advantageous cannot be assessed without additional testing. Conversely, a cortex that appears relatively intact on MRI is not necessarily functionally intact. The notion that there are functions left intact in developmental disorders is likely incorrect; massive reorganization is likely standard across developmental disorders, and the resultant functionality is probably deviant (Karmiloff-Smith et al., 1997; Mills et al., 2000; Thomas and Karmiloff-Smith, 2002; Grice et al., 2003). In particular, language processing, musical abilities, and face processing in WS are not par with normal performance (Karmiloff-Smith et al., 1998, 2004).

Overall, this is fascinating work, not least because it's a welcome corrective to the simplistic interepretations that are sometimes given to the relative sparing of linguistic abilities in this syndrome.

Think on, think off

Almost two weeks after Geoff announced the end of his public radio station's pledge drive, I'm still suffering through mine. This morning, I heard this wonderful attempt to break up an idiom (paraphrasing slightly; I didn't record the exact quote):

We know you've been thinking about becoming a member off and on during our pledge drive. This morning, we want you to think about it on.

[ Comments? ]

Save those scraps

A big posthumous payday for Norman Mailer's mom.

Better a spectacular blunder than a hint of unseemliness

In the April 25 New Yorker, pages 2 and 3 are a spread for the "all-new Infiniti M". The right-hand page shows a driver's view of the high-tech cockpit in glowing beige and brown. Above the picture, a few words of normal-looking text tell us about the Lane Departure Warning System, the Bose Studio Surround Sound, the Bluetooth Wireless Technology, and the exhilarating 335 horsepower.

On the left-hand page, the cockpit photo fades elegantly into a warm brownish blackness, against which enormous glowing off-white letters are laid out as if on a surface slanted away from us toward the center of the spread -- an open driver's door? -- with textual perspective lines leading us back into the picture to the right:

Designed to think the way you do, the technology is smart, simple and invisible. A fresh new contemporary space that takes luxury into the wireless modern world it belongs.

Uh, like, "to"? Or "in"?

Unless I'm being really dense, or missing some language change in progress here*, that second sentence is ungrammatical. Not non-standard-English ungrammatical, not made-up strunkadelic pseudo-rule ungrammatical, but just plain everybody-knows-it's-wrong inco-freaking-rrect.

What's the story here? This two-page ad must have cost Nissan North America about $200,000 to run, and Lord knows how much to design, so we can assume that the copy was proofread once or twice. Surely this is not a typo.

Well, I have a theory.

Although "to" or "in" would fit the lay-out easily, the other obvious alternative wordings wouldn't: "the wireless modern world where it belongs"; "the wireless modern world to which it belongs"; "the wireless modern world in which it belongs". For any of these, you'd have to change the font sizes and redo all the line divisions. That would be hard, since the existing lines are only 15 or 16 characters long. To add the five characters of "where" or the eight characters of "to which" would take some big changes, spoiling the whole feel of the lay-out.

So here's what I think happened. The copy started out as "...the wireless modern world it belongs in", or "... the wireless modern world it belongs to". Then at the last minute, someone at Nissan North America looked at the ad and said "Wait a minute, that sentence ends with a preposition. What will people think?"

The ad agency team (from TBWA\Chiat\Day, according to BrandWeek) trotted out the usage books that say stranded prepositions are OK, and even the fake Churchill quote. But the auto execs weren't having it: "This is a luxury car, you can't use that tacky syntax!" What to do? There was no room for "where" or "to which", and no time to re-do the whole thing. Other local substitutions raised other troubling associations: "the wireless modern world it controls"? "... deserves?" "... inhabits"? "... inherits"? "... traverses"? In desperation, they decided to leave the preposition out, hoping that most people wouldn't notice. Better a genuinely mistaken sentence than the social anxiety associated with violating an absurd "rule" that was invented out of thin air by John Dryden in 1672 and has been scorned by every competent expert since.

This is all just a theory, mind you. I'll let you know if I hear another story from anyone in a position to know.

* To be fair, it's not totally out of the question that some people might be moving in the direction of using "belong" with a location as direct object. There's a model in relative clauses with the place as the head:

Lay out all the cards and the drawings and work with your child to match each machine with the place it belongs.

The place that I belong right now is home.

However, other words of similar meaning don't work for me in the same construction:

???...match each machine with the location it belongs.

???The location that I belong right now is home.

...though Google finds a few people who think this sort of thing is fine:

...copy the new directory into the location it belongs.

...returning anything out-of-place to the location it belongs.

Either send it to the location that it belongs or send it to Susan Fanning and ask that she forward it to the proper person.

Even place doesn't work for me other than in such relative clauses:

*This machine belongs that place.

and in this case, Google doesn't seem to find any native speakers who disagree with me. I think this is something about place, not something about belong. All these internet examples (with place as head and other verbs in the relative clause) are fine for me:

Check out the place that we're going, Burke's Canoe Trips,

All the places I've looked just have it up for sale without listing what the

DVD contains.

Congress needs a crash course in Internet technology followed by a swift kick

in the place it sits.

even though all the non-relative-clause versions strike me as hopeless or at least questionable even with place, and worse with other noun phrases for locations:

*We're going a place on the river.

*We're going Burke's Canoe Trips.

?I've looked many places.

*I've looked many music stores.

*He's sitting a place halfway between his shoulder blades and his knees.

*He's sitting his rear end doing nothing.

The string "the world that it belongs" occurs 40 times in Google's index, and none of them have the structure required by the Infiniti ad. The string "the world it belongs" occurs 1,940 times, mostly irrelevantly:

Before Him, individual distinctiveness belongs to the 'nothingness' of being in the world. It belongs on a basis that is not God...

And the world it belongs to me...

But world music is still something that belongs to the world. It belongs to the people.

There are too many for me to want to check them all, but after looking at the first couple of hundred hits, I don't think we're going to find anything like the structure used in the Infiniti ad. If there's a change in that direction, it's way too early to use it in a luxury car ad.

[Update 4/29/2005: Neal Whitman emails:

I've noticed the kind of missing preposition that you noticed in the Infiniti ad, too. Sometimes I think the situation is what you hypothesize. In fact, I think your analysis of this ad is on the money, since it really does sound bad. Other times, though, deletion of the preposition can be gotten away with:

1. It works with antecedent-contained deletion. For example, someone giving me advice on exiting a tight parking space said, "Go out at the angle you came in." Not "...at the angle you came in AT." But the key is that the 'at' already appears earlier in the sentence. I'm not sure of the exact conditions when this can happen, but I'm pretty sure the name for it is "antecedent-contained deletion." In this case, the preposition omission is almost obligatory, since (to my ear) the repeated 'at' sounds funny, even though it parses out right. In fact, maybe the 'into'/'to' repetition was close enough to activate the ACD rule in the ad-writers' grammar, but just not in yours or mine.

2. Or, as you note, the noun heading the adverbial relative clause might be a special one such as 'place,' which allows the omission of a needed preposition. These have been written about by Richard Larson in a couple of LI papers in the 1980s, and by McCawley. And by yours truly, in a 2002 issue of Journal of Linguistics (where full bibliographic info on the other sources is listed).

That's Whitman, N. (2002) " A categorial treatment of adverbial nouns." Journal of Linguistics 38.521-597]

[Update 5/1/2005: Andrew Palumbo observes that I could use negative conditions like -"belongs there" to eliminate spurious matches (along perhaps with some real ones) from the Google search for other examples of phrases like "into the world it belongs". The search {"into the world it belongs" -"belongs there" -"belongs to" -"belongs in"} returns nothing at all; {"into the * world it belongs" -"belongs there" -"belongs to" -"belongs in"} returns one spurious hit; {"into the * * world it belongs" -"belongs there" -"belongs to" -"belongs in"} returns only this very page itself!

We can combine negative conditions with a wildcard "*" {"into the * it belongs" -"belongs there" -"belongs to" -"belongs in" -"the place it -"the places it"} to find 94 possible examples of this construction with head words other than place or places, such as

Either move in behind it, or pass it, giving it opportunity to move back into the lane it belongs.

As you continue to evaluate, improve, and adjust it will bring your marriage back into the arena it belongs.

...you have to make your trail map narrow to fit say 400 or 450 pixels wide to get that map back into the area it belongs...

Ask the priest to go kick some other church's backside into the spot it belongs.

The ABRA's goal is not to take over the barrel racing industry, but rather to take the barrel racing industry back into the Hands it belongs.

The title of Chapter 18 puts oral sex into the context it belongs...

Album reviews, like most other reviews, should either give the album kudos, or knock it into the shitcan it belongs.

All of these strike me as pretty bad, but after I've read 50 or 60 of them in a row, they're beginning to move out of the WTF category. ]

Habemus or abemus?

I only just noticed, when NPR played back a selection of "voices of the week" this morning, that what Cardinal Estevez actually said as he announced the choice of Cardinal Ratzinger was (in phonetic transcription) [a'bemus 'papam]. No [h] on the first word. According to the St. Louis Review, the weekly newspaper of the archdiocese of St. Louis, "At 6:40 p.m., Chilean Cardinal Jorge Medina Estevez, the senior cardinal in the order of deacons, appeared at the basilica balcony and intoned to the crowd in Latin: "Dear brothers and sisters, I announce to you a great joy. We have a pope." Well, I'm sure it was supposed to be in Latin, but unless I am much mistaken, Latin would have had that [h]. Hence the spelling. Of course, I am not philologist enough to know the exact century when the [h] disappeared (as it certainly did: there is no [h] in Spanish or French or Italian, and I can't name any modern Romance language that has preserved it; philologist acquaintances, please correct me if I'm wrong), so the Cardinal could perhaps be defended on the grounds that he using the Latin of some later period when the [h] as already gone. But my money would be on the simpler hypothesis that he speaks Latin with a Chilean Spanish accent you could cut with a knife.

[Added later: Actually, just about everything in this post is wrong except that Cardinal Estevez may indeed come from Chile and may have spoken at roughly twenty to seven. Many philologist acquaintances and even total strangers have rebuked me on Latin pronunciation issues, some very sternly indeed. Click here awful details of my rank ignorance. It's going to be a long time before I get invited to any classics parties or Catholic church events, that's for damn sure.]

April 24, 2005

The King of Linguistics

Thanks to Mark Liberman's having pointed us to the amaztype zeitgeist site, I can now report that the title of King of Linguistics has been taken, by one Andrew Laidlaw, a young white UK hip hop artist who performs under the name MC (or M.C.) Unique. The title is, presumably, a boast about his facility with the English language.

How did I find this out? Well, first, zeitgeist informed me, a few minutes ago, that LINGUISTICS had now pushed PHP out of the #10 slot in the rankings of words recently requested by users of amaztype (which spells out words using thumbnails of titles, from the amazon.com database, with those words in them). (Meanwhile, LANGUAGE is holding on at its recently achieved #3 position, behind SEX and FUCK.) So I went to the amaztype homepage and checked on LINGUISTICS in book titles; there are, no surprise, a great many such titles. No dvd or video titles with LINGUISTICS in them, however. And only one music title with LINGUISTICS in it: yes, MC Unique's "The King of Linguistics", named after one of the raps on the cd.

While I was playing with the software, I checked out LINGUIST. No music, but there's a series of dvds entitled "X 101 (Learn to Speak X wiith the Travel Linguist)", where X is French, German, Italian, (Brazilian) Portuguese, or Spanish.

But it's shocking that linguistics and linguists haven't been celebrated in the titles of music and films. "Lay, Linguist, Lay". "The Lilt of Linguistics". "Let Me Call You Linguist". "The Lady from Linguistics". "Lassie Saves the Linguists". "The Last Linguist". So many possibilities, not one of them yet exploited.

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

Tho Fan

Here's a welcome contrast with the shabby treatment of Said el-Gheithy, the inventor of Ku (= "Ch'toboku").

When Stephen Totilo wrote on 4/19/2005 in the NYT about the language Tho Fan, invented for an X-Box game called Jade Empire, linguist Wolf Wikeley is front and center. With a picture and everything.

Here's a welcome contrast with the shabby treatment of Said el-Gheithy, the inventor of Ku (= "Ch'toboku").

When Stephen Totilo wrote on 4/19/2005 in the NYT about the language Tho Fan, invented for an X-Box game called Jade Empire, linguist Wolf Wikeley is front and center. With a picture and everything.

Now we need to work on those linguists' consulting fees. The NYT article says that that BioWare paid Wolf "just over $2,000" for four months of work. Unless he gets big-time residuals, that must be way under minimum wage, even if it was US dollars rather than Canadian ones. (And the University of Alberta Linguistics Department web site suggests that he had to take a leave to do it.) I'm sure BioWare can't get programmers or graphic artists to work for wages like that.

Wikely says he had fun ("This was really a dream job because as a hobby I write and as a profession I work with languages so to combine those, working creatively and scientifically, was a blast"), but all the more reason to give him a proper payday, says I.

[The University of Alberta press release is here.]

Rampant malaprops, companionable

Not all substitutions of one word for another are eggcorns: some are typos, some are misspellings, some are mishearings, and some are plain old malapropisms, not involving any sort of reinterpretation or reanalysis. Of the malaprops, a few have become rampant, usually because the words in question are similar both semantically and phonologically: militate/mitigate, flout/flaunt, and flounder/founder are familiar examples (and the first two are discussed in the eggcorn database).

New to me, though probably not to more experienced collectors of these things, is eccentric/eclectic, as in the following:

Some of the most fascinating passages of the book are anecdotes in the first chapter about Bouissac's adventures with lions and bears. To dream of running off to join a circus is clichéd; to actually do so is eclectic. (Ken Schellenberg, review of The Pleasures of Time: Two Men, A Life by Stephen Harold Riggins, Lambda Book Report, Jan.-March 2005, p. 25)

I really can't see how running off to join a circus is an eclectic action, in the sense that it combines diverse elements of something or other. But eclecticism is both odd and conspicuous, so you can see how thinking about eccentricity might lead you to eclecticism. Especially when the words eccentric and eclectic are so similar phonologically (and morphologically). If you reach for a fancy word that has the meaning you want, eclectic is likely to be close to hand.