July 31, 2006

Automatic asterisking

My mail box overflows with information about taboo language in the world of rock music, including several suggestions that the odd awarding of asterisks in iTunes music store listings is the result of a script that does the asterisking automatically, and therefore can't block words that have significant non-taboo uses. I resisted this idea at first -- it seemed so, well, stupid, scarcely an effective way of protecting young minds from dangerous content -- but some research shows that this is almost surely so. Here's the system, as it was working today:

1. The search software accepts a taboo word as input, and finds everything with that word in it (yes, there are some occurrences that escape asterisking, as I'll demonstrate below), AND everything with the asterisked version of the word in it. So a search on cock pulls up occurrences of "cock" and also "c**k". The search ignores case ("dick" and "Dick" are the same word), apostrophes, and hyphens. And deals only with whole words, so fuck or fucks won't get you the band The Crucifucks. (Joe Salmons and Monica Macaulay, in their 1988/89 Maledicta piece "Offensive rock band names: A linguistic taxonomy", awarded the prize to Crucifucks. The band is still in print, I see.)

2. Asterisking preserves the number of letters in the word, and the first and last letters. So:

3. Asterisking affects the song titles and the album titles, and with (so far as I can tell) perfect consistency -- but, bizarrely, NEVER affects the name of the artist(s). So we get:

Artist: Anal Cunt. Artist: Mary's Cunt. Their song: "Mary's C**t -- Pitbull Pete".

Artist: Holy Fuck. Album by them: "Holy F**k".

Artist: Crazy Penis. Artist: Penis Flytrap. Song by them: "P***s Flytrap | Wait".

Artist: The Piss Drunks. Artist: Piss Ant. Album by them: "P**s Off".

Artist: Nashville Pussy. Album by them: "Let Them Eat P***y".

Artist: Suck It To Ya. Album by Boris the Sprinkler: "S**k". Song by Dude Offline: "You S**k, You Drank My Beer!"

No human intelligence is applied in any of this. "Piss" is asterisked even when it doesn't refer to urine or urinating. Non-fellatial "suck" is asterisked. "Balls" is not asterisked, even in the song title "Blue Balls".

4. The obvious miscreants (and their variants) are asterisked; these words count, in some people's minds anyway, as taboo vocabulary across the board:

On the other hand, words that have significant non-sexual uses aren't asterisked:

Nor are a few words that must have seemed to the iTunes folks to be technical or medical:

There's a fine line here between these words that make it through the filter and "masturbate", "penis", and "vagina", which don't. (Another bit of oddness is the fact that "rape" escapes the iTunes filter.)

One wonderful result of all of this is Lil' Kim's track listed in iTunes as "S**k My Dick".

[Final disclaimer: I make no claim to completeness in these lists. Update 8/1/06: Though still scratching my head about a world in which "masturbate" is a dirty word, but "rape" is not, I've checked out some more vocabulary. A nice minimal pair: "blow job" is ok, because each word on its own is ok, but "blowjob" turns into "b*****b". "Bullshit" is, of course, out. "Turd" is out, but "crap", "poop", and "fart" are ok. And "fag" and "faggot" are out, but "gay". "queer", "homo", and "dyke" are ok.]

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

Virtues, pleasures and myths

Geoff Pullum's note on F.A.N.B.O.Y.S. — a mnemonic acronym for the (alleged) English "coordinating conjunctions" for, and, nor, but, or, yet, & so — reminded me of the list at the end of the Ladies' and Gentlemen's Guide to Modern English Usage by James Thurber:

You might say: "There is, then, no hard and fast rule?" ("was then" would be better, since "then" refers to what is past). You might better say (or have said): "There was then (or is now) no hard and fast rule?" Only this, that it is better to use "whom" when in doubt, and even better to re-word the statement, and leave out all the relative pronouns, except ad, ante, con, in , inter, ob, post, prae, pro, sub, and super.

I expect that most people who learned Latin the old-fashioned way will recognize that list, and may even remember what it's a list of. (It's prepositions, not relative pronouns -- and similarly, the FANBOYS list is a mixed bag of central coordinators, unusual coordinators, marginal coordinators, and adverbs commonly used as connective adjuncts.). Here's the source of Thurber's list, in Allen & Greenough's New Latin Grammar for Schools and Colleges chapter 370:

370. Many verbs compounded with ad, ante, con, in, inter, ob, post, prae, prō, sub, super, and some with circum, admit the Dative of the indirect object:—

1. “neque enim adsentior eīs ” (Lael. 13) , for I do not agree with them.

2. “quantum nātūra hominis pecudibus antecēdit ” (Off. 1.105) , so far as man's nature is superior to brutes.

3. sī sibi ipse cōnsentit (id. 1.5), if he is in accord with himself.

4. “virtūtēs semper voluptātibus inhaerent ” (Fin. 1.68) , virtues are always connected with pleasures.

5. omnibus negōtiīs nōn interfuit sōlum sed praefuit (id. 1.6), he not only had a hand in all matters, but took the lead in them.

6.“ tempestātī obsequī artis est ” (Fam. 1.9.21) , it is a point of skill to yield to the weather.

7.“nec umquam succumbet inimīcīs ” (Deiot. 36) , and he will never yield to his foes.

8.“cum et Brūtus cuilibet ducum praeferendus vidērētur et Vatīnius nūllī nōn esset postferendus ” (Vell. 2.69) , since Brutus seemed worthy of being put before any of the generals and Vatinius deserved to be put after all of them.

... and so on. (Emphasis added.)

I remember this list because James Thurber and I were taught Latin by methods that rewarded us for memorizing such things. Thurber seems to have had mixed emotions about the experience, and so do I.

Here's how it worked. For each class meeting, we were expected to prepare the next chunk of Caesar, Cicero, Virgil, Tacitus or whatever we happened to be struggling through. Then students would be chosen at the teacher's whim, one after another, to read the passage, sentence by sentence, and translate it. After the translation of each sentence came a grammatical interrogation.

For example, if we were reading the part of Cicero's De Finibus Bonorum et Malorum where the business about virtues being connected with pleasures comes from, someone would have to stand up to recite and construe I.68:

Quocirca eodem modo sapiens erit affectus erga amicum, quo in se ipsum, quosque labores propter suam voluptatem susciperet, eosdem suscipiet propter amici voluptatem. quaeque de virtutibus dicta sunt, quem ad modum eae semper voluptatibus inhaererent, eadem de amicitia dicenda sunt. praeclare enim Epicurus his paene verbis: 'Eadem', inquit, 'scientia confirmavit animum, ne quod aut sempiternum aut diuturnum timeret malum, quae perspexit in hoc ipso vitae spatio amicitiae praesidium esse firmissimum.'

Hence the wise will feel the same way about their friends as they do about themselves. They would undertake the same effort to secure their friends' pleasure as to secure their own. And what has been said about the inextricable link between the virtues and pleasure is equally applicable to friendship and pleasure. Epicurus famously put it in pretty much the following words: "The same doctrine that gave our hearts the strength to have no fear of ever-lasting or long-lasting evil, also identified friendship as our firmest protector in the short span of our life. [Translation by Raphael Woolf, published as ("On Moral Ends", 2004]

Usually, the teacher would not directly criticize the English version, which the more diligent and less facile students might have memorized from one of the forbidden interlinear translations that we called "trots". (In the UK, I understand that these were called "cribs".) Instead, the teacher would probe the student's understanding of the structure.

For example, he might ask you to "tell us about inhaererent." In response, he'd want the principal parts (inhaereo, inhaesi, inhaesum) and the form in this instance (imperfect subjunctive active 3rd person plural). Then he might ask "why should it be in the subjunctive?", "what is its subject?", etc. Eventually he'd get to voluptatibus. It's the plural ablative or dative of voluptas, sir. Well, make up your mind, which one is it? Um, ablative, I guess. Really? Can you tell us why? Um, uh, ablative of specification, sir. Nice to see that you've finally learned some grammatical terminology, Liberman, but that's not the answer we're looking for here. Anyone else?

And some obnoxious swot who has memorized the whole grammar book (I won't name names) pipes up smugly from the back row: "Sir, verbs compounded with ad, ante, con, in, inter, ob, post, prae, pro, sub, and super admit the Dative of the indirect object." Dative of the indirect weenie, if you ask me.

Now the trick here is that Latin noun forms in -ibus are generally ambiguous between the dative plural and the ablative plural. So to name the case, in any given example, you need to decide what the construction is, and deduce from that whether the dative or the ablative would have been used, if a word had been chosen where you could tell the difference.

The result is an elaborate functional taxonomy of the Latin case system -- the Datives of Agency, of Reference, of Purpose or End, of Service, of Fitness, the Ethical Dative, etc. -- which gave me endless trouble when I was a student. For a long time, I thought this was because I skipped first-year Latin, and was thrust directly into construing Caesar's Gallic Wars, sink or swim. (Similarly, my father, who was color blind, thought for years that he must have been out sick when they taught about colors in school.) And when I tried to memorize the terminology, I always got distracted by the examples. (Did Cicero really say that virtues are always connected with pleasures? No, alas, it turns out that he puts these words into the mouth of Torquatus, and argues against them. Cicero was no Epicurean.)

Content aside, many of the examples struck me as subject to more than one interpretation, falling in the cracks between the case-taxonomy categories. And in fact, the role of voluptatibus in the line adapted from Cicero, virtutes semper voluptatibus inhaerent, is a case (so to speak) in point. Allen & Greenough might cite it as an example of how "verbs compounded with ad, ante, con, in, ... admit the Dative of the indirect object", and Lewis & Short's entry for inhaereo might quote the same (modified) quote in a list of examples of inhaereo with the dative. But Allen & Greenough add that:

In these cases the dative depends not on the preposition, but on the compound verb in its acquired meaning. ... The construction of § 370 is not different in its nature from that of §§ 362, 366, and 367; but the compound verbs make a convenient group.

Convenient for them, maybe. Tracking down the cross-references, we learn that:

362. The Dative of the Indirect Object with the Accusative of the Direct may be used with any transitive verb whose meaning allows (see § 274).

366. The Dative of the Indirect Object may be used with any Intransitive verb whose meaning allows.

367. Many verbs signifying to favor, help, please, trust, and their contraries; also to believe, persuade, command, obey, serve, resist, envy, threaten, pardon, and spare, take the Dative.

It's not clear to me whether inhaerent in this phrase is really an example of an intransitive verb whose "meaning allows" the Dative of the indirect object -- there's no (literal or metaphorical) transfer of substance from virtues to pleasures, for instance. And Lewis & Short start the entry for inhaereo with a bunch of examples where it takes the ablative case:

I.(a). With abl.: sidera suis sedibus inhaerent, Cic. Univ. 10 : animi, qui corporibus non inhaerent, id. Div. 1, 50, 114 : visceribus, id. Tusc. 2, 8, 20 : constantior quam nova collibus arbor, Hor. Epod. 12, 20 : occupati regni finibus, Vell. 2, 129, 3 : prioribus vestigiis, i. e. continues in his former path, Col. 9, 8, 10 : cervice, Ov. M. 11, 403 .

Their second example of inhaereo taking the ablative (animi, qui corporibus non inhaerent = "souls which aren't connected with bodies") strikes me as similar in meaning to the example we started with (virtutes semper voluptatibus inhaerent = "virtues are always connected with pleasures").

Well, if I'd brought all this up in Latin class, Mr. Mansur would have accused me of being a Philadelphia lawyer, and told me to get on with Cicero or sit down. And you're no doubt reacting in a similar way.

I do have a point, though. Brett Reynolds' post on FANBOYS observes that lists and hierarchies of this kind are "myths" that "[give] the faithful a comfortingly simple handhold in a confusing world". I'm sure that this is true -- but such myths can be confusing and even disturbing, not comforting, for those who think about them too seriously. In secondary-school Latin, I was torn between believing that the whole grammatical apparatus was a well-founded logical structure that I might grasp some day, if I applied myself, and seeing it as a mass of half-digested confusion, as the grammarians themselves sometimes seemed to admit:

As the Romans had no such categories as we make, it is impossible to classify all uses of the ablative. The ablative of specification (originally instrumental) is closely akin to that of manner, and shows some resemblance to means and cause. [Allen & Greenough, 418.a.]

It came as a breath of fresh air when I took a linguistics course in college, and learned that modern grammarians offer systematic arguments for their assumptions, categories and analyses, and that they sometimes admit that they are wrong. Well, they more often admit that their colleagues are wrong, but collectively it comes to the same thing.

July 30, 2006

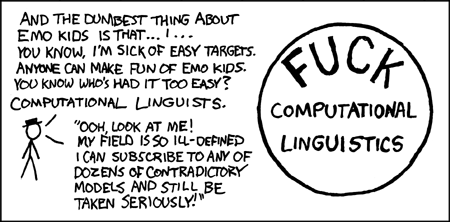

On the taboo watch: The rock report

We're staying on the alert here at Language Log Plaza for the way taboo vocabulary is deployed, or avoided, in various settings, from the prim pages of the New York Times to the maximally immodest covers of gay porn magazines. Today we're enjoying a musical interlude, a brief look at taboo language in rock music.

Language issues come up in four places: in lyrics, in song titles, in album titles, and in band names. Song titles, album titles, and band names present some of the same problems as porn magazine covers, since they will be displayed in public, on album covers and on play lists. (All four are on display at concerts, of course). Rock music is sturdily defiant, so you see people pushing the language line pretty hard in all four places, and eventually in visual materials as well (most famously, with the poster for the Dead Kennedys' album "Frankenchrist").

I'm hoping that somebody's done a more thorough study of taboo topics and language in popular music, because there's a whole lot there and I'm just giving a tiny sample here. [Update 7/31/06: Greg Stump points us to the Sonic Breakdown entry for fuck, where the section "Notable fuck bands" gives a capsule history of this particular word in music.] There's a long pre-rock history of suggestive lyrics: "It ain't the meat, it's the motion", "She got pinched in the As / tor Bar", all those versions of Cole Porter's "Let's Do It", and much much more. Eventually the fuck hits the rock fan, obscenity laws are challenged, ratings systems are proposed, and Tipper Gore enters the arena. Rap/hip-hop has been a scene of obscenity contention for twenty years now, with 2 Live Crew as the most famous early offenders.

Along the way we have people choosing band names that are right up against the line -- the Butthole Surfers -- and then over it, as with this Toronto band, as described by a fan:

[Thanks to Tom Limoncelli for the pointer to the band.] You'll note the initialism "H.Y.F.Y." -- usually given as "HYFY" -- which provides a way to refer to the band without being officially obscene. [Update 7/31/06: A number of correspondents have now nominated the band Anal Cunt for the Bad Taste Palm.]

Album titles follow the same arc, with Gene Simmons's 2004 "Asshole" a recent entrant in the deliberate-offense sweepstakes. (Well, it's Gene Fuckin' Simmons.)

Then there are the song titles. Sometimes songs with taboo lyrics are given neutral titles: Nine Inch Nails's "Closer" and Pansy Division's "Anthem", for instance. This works for public display, but fans often refer to these two songs via their central lines anyway, as "I want to fuck you like an animal" and "We're the buttfuckers of rock and roll", respectively, from:

I want to feel you from the inside

We're the buttfuckers of rock and roll

We wanna sock it to your hole

Pansy Division has also been known to take the route of avoidance by initialism, as in their song "C.S.F.", a gay male re-working of the defiant anthem "Colored Spade" from Hair, which begins:

A fuck bunny, fruitcake, cum superdeli, homo

But mostly Pansy Division just puts those words right out there in the song titles: -- "Fuck Buddy", "Cocksucker Club", "Political Asshole", "He Whipped My Ass in Tennis, Then I Fucked His Ass in Bed" -- and prints them on their albums, presenting a problem for Apple's modest iTunes music store. The iTunes store asterisks out the usual suspects: "The C********r Club" (yes, eight asterisks, all in a row), "Political A*****e", "...F****d His...". Remarkably, iTunes also avoids "ass" ("Two Way A*s" and "He Whipped My A*s in Tennis...") and even "slut" ("I'm Gonna Be a S**t"). You can see that their asterisking is systematic: preserve only the first and last letters. But their choice of words to asterisk is puzzling; "ass" and "slut" are out, but "dick" gets by (in "Dick of Death"), and so does "jack off" (in Prince's "Jack U Off", covered by Pansy Division). Once again, "dick" and "cock" seem to be on different sides of the offense boundary.

As for the words, sometimes they seem to be there primarily as a gesture of defiance (as in "C.S.F.") or insult [Update 7/31/06: A Bad Taste Palm to Jimi Lalumia and the Psychotic Frogs, for their thoroughly nasty cover of "Eleanor Rigby", with the refrain line "All you fuckin' people".], but in some cases they're pretty much intrinsic to the content. A lot of rap/hip-hop is about sex, and virtually all of Pansy Division's energetic and cheery songs are, and both naturally use everyday vocabulary for talking about sex. HYFY.

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

US Continues to Fire Gay Language Specialists

The US military continues to fire badly needed language specialists, including specialists in Arabic, because they are gay. The latest case, described in this news report, indicates that they are actually becoming more agressive and not abiding by their stated policy of "don't ask, don't tell". Arabic specialist Bleu Copas was dismissed after an eight month investigation triggered by anonymous emails. Apparently the "War on Terror" justifies patently illegal warrantless wiretapping but not easing up on the war on homosexuals in order to retain people with badly needed skills.

July 29, 2006

Summer homes and strawberry rhubarb pie

An article about Art Buchwald in the garden section (of all places) of the New York Times (here) descrbes his love for his "summer home." The rich and famous in large Eastern cities seem to have one of these homes to use as a retreat from work and the hustle-bustle of urban life. It's also a place where friends and relatives can visit. Even though he's now 80 and dying, Buchwald loves getting company. People like Walter Cronkite, Dave Barry and Carly Simon drop by regularly. He chose this summer home as the place to spend the waning days of his life. And he's still writing his syndicated columns. The article made me think a bout the "summer homes" of linguists and other academics.

Sometimes our salaries don't allow us the luxury of even one home, much

less two. But we can use our summer break time to give lectures or

teach courses in other places, attend conferences, and mostly do our

research and writing--because we love what we do. Some pick nice places

to do their research, like the mountains of Montana, where my fellow

Language Logger, Sally Thomason, researches the Salish language in the

Flathead. Before I moved to Montana I used to spend parts of my summers

here, my wife's home state, and I fell in love with this place. When I

retired from teaching at Georgetown, we moved here and, like Buchwald,

we made it our permanent "summer home." I now do my writing and

research here, far from the madding crowd (and any loose gerunds that happen

to be running around).

But it was the last quote in this article about Buchwald that hit me

between the eyes. His housekeeper broke into his conversation with the

interviewer and asked if he'd like some strawberry rhubarb pie:

He was where he wanted to be, doing what he wanted to do. How many people can say this? But that's what loving your work and doing it in the place you love can do for you. From all I can tell, most linguists dearly love their work and even do it in their spare time. They may not always love living where their jobs are, but they can usually find "summer homes" of sorts to help take care of that need. And they can move to those places when they retire, getting the best out of both work and home. When this happens, like Buchwald, they can be so happy that they can't do anything different. And they can have their strawberry rhubarb pie whenever they want it.

Roses of Mohammad for breakfast, elastic loaves for lunch...

Back in January, the edict came down in Tehran that Danish pastries (shirini danmarki) should henceforth be called "roses of Mohammad" (gul-e-muhammadi). At the time, this seemed to be a specific reaction to the Danish cartoon controversy; but it seems that the Farhangestan -- Iran's equivalent of the Academie Française -- has a much longer hit list, including pizza (now to become "elastic loaf") and helicopter (now to be "rotating wing"), and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad has decreed that the changes should be mandatory for official documents, schoolbooks and newspapers. The Reuters article observes that "[t]he words created by the Farhangestan as replacements to European loan words often sound cumbersome or comic to Iranians". None of the English-language news articles so far give the recommended Persian (or if you prefer, Farsi) circumlocutions.

My favorite example of this genre is the attempt some years ago, by one of the Francophone language-policing bodies, to replace "bulldozer" with "tracteur à lame horizontale" (= "horizontal-bladed tractor"). This was so completely unsuccessful that the proposed replacement now has a Google count of zero.

[Hat tip: Gwynn Dujardin.]

[Update -- Abnu at Wordlab pointed me to a paper by Ebrahim Monajemi, "Can ethnic and minority languages survive in the context of global development?", which gives some further details about the Farhangestan organization:

One of the academic cultural centers which tries to keep the Persian language free of alien words is the Academic Center of Persian language and literature or the department of Farhangestan-e-Zaban Va Adab Farsi. This organization has the duty to coin or adapt new words for the non-Persian ones. It consists of 25 Persian language experts and professors who are the final decision-makers. There are several specialized sub-departments such as Engineering, Medicine, Agriculture, Transportation, Military, Economic, and so on, that cooperate with the Center.

Farhangestan-e-Zaban VA Adab Farsi is responsible for coining the new Persian words against New Latin ones using by people or may be used in future. This organization follows the below procedures to coin or adapt appropriate words for the Latin ones. Its main policy is as follows (Farhangestan-e- Zaban-2001):

1. In coining and choosing a new word, Persian phonetic rules and learned speakers’ way of talking and Islamic points of views should be regarded as criterion.

2. Phonetic rules should be obeyed according the Persian way of talking.

3. New words that are found or created should follow the Persian grammatical rules for coining nouns, adjectives, verbs and so on.

4. New words should be chosen or coined out of the most common or frequent words that have been used since 250 AD.

5. New words can be chosen from among the most frequent and common Arabic words, as they are used in Persian.

6. New words can be chosen out of the middle and Old Persian languages

7. There should be only one equivalent in Persian for any of the Latin ones, particularly for technical words.

8. It is not so much necessary to adapt or create new Persian words for those Latin words which have been used internationally and globally.

It's not clear to me why "pizza" wouldn't count as one of "those Latin words which have been used internationally and globally".

Anyhow, searching for {Farhangestan Zaban} turns up quite a bit of other interesting information, including http://www.persianacademy.ir. ]

They sure is

Family get-togethers can be tough for little ones -- they want to stay up and have fun with everybody else, but the adults keep trying to calm them down and get them to go to bed. Last night we set up sleeping spots for our niece (2 1/2) and nephew (6 1/2) in the living room, turned down the lights and put a movie on to keep them entertained. Their father says to them: "Lie down and watch the movie." To which my niece replies: "We're am!"

[ Comments? ]

F A N B O Y S ?

Brett Reynolds in the inaugural post of his new blog comments on something that baffled him when he first began college teaching: FANBOYS. I hadn't heard of this before either. FANBOYS is nothing to do with fangirls. Says Brett:

The first time I walked into our writing centre, I noticed that FANBOYS was pasted in large letters across one wall. While many readers may be familiar with FANBOYS, I'd never heard of them, but according to many freshman writing textbooks, FANBOYS is a mnemonic for the co-ordinating conjunctions in English (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, & so).

This is supposed to be a list of words that pattern alike. (Check it out. They do not.) Much of what traditional grammar says about the purported "co-ordinating conjunctions" is a mess, like what it says about the pseudo-class of "conjunctions" generally; The Cambridge Grammar tries to straighten this out. Brett explains some of the more complex reality very nicely, and he also understands what makes an easily memorized oversimplification so seductive: "it gives the faithful a comfortingly simple handhold in a confusing world." It does indeed. A lot of style and grammar guide authors must look at a list of desiderata such as (1) simple, (2) memorizable, and (3) accurate, and think to themselves, two out of three isn't bad.

James J. Kilpatrick, grammarian

A couple of weeks ago, James J. Kilpatrick opened his column with an astonishing piece of linguistic misanalysis (July 16, 2006, "Even a little ambiguity"):

This was a headline in USA Today on April 28: “Mass Transit Not an Option for All Drivers.”

Did you wince? Roll your eyes? Did you groan? Then you have the soul of a grammarian, and will go to heaven when you die…. There you will lecture the seraphim on the distinction between “all” and “not all,” and you will explain to them that if mass transit is not an option for “all” drivers, it cannot be an option for even one driver.

Neal Whitman at Literal Minded ("If It’s Not for Everyone, It’s Not for Anyone" 7/21/2006) called Kilpatrick to account. As any linguist would, Neal explained the offending ambiguity in terms of the relative semantic scope of the negative not and the quantifier all -- in heavy English rather than predicate calculus, it's the difference between "it's not the case that mass transit is an option for all drivers" and "for all drivers, it's not the case that mass transit is an option."

And as any sensible speaker of English would, Neal observed that Kilpatrick is full of it when he asserts that "if mass transit is not an option for 'all' drivers, it cannot be an option for even one driver".

Neal's evidence was his own linguistic intuition:

[I]n Mass transit [is] not an option for everyone, the most natural reading for me ... is the one the headline writer intended, the one with the wide-scoping negation...

My intuition agrees with Neal's, and we could cite evidence from published studies to the effect that most native speakers of English agree with the two of us rather than with Kilpatrick. But instead, since Kilpatrick is an authoritarian conservative who cares little for the opinion of the vulgar mob, I'll invoke the authority of respected authors over the centuries. When Kilpatrick starts giving his grammar lessons in the streets of paradise, there are going to be a lot of giggles from the better-informed pedestrians.

Anthony Trollope, The Last Chronicle of Barset, vol II, chap. LXXI:

The solution of the mystery was not known to all,---was known on that night only to the very select portion of the aristocracy of Silverbridge to whom it was communicated by Mary Walker or Miss Anne Prettyman.

= it was not the case that the solution of the mystery was known to all

≠ the solution of the mystery was unknown to allHerman Melville Mardi and a Voyage Thither vol. 1 chap. LXXXIV

But the imperial Marzilla was not for all; gods only could partake; the Kings and demigods of the isles; excluding left-handed descendants of sad rakes of immortals, in old times breaking heads and hearts in Mardi, bequeathing bars-sinister to many mortals, who now in vain might urge a claim to a cup-full of right regal Marzilla.

Joseph Glover Baldwin: The Flush Times of Alabama and Mississippi (1853), "Ovid Bolus, Esq., Attorney at Law and Solicitor in Chancery":

He did not confine himself to mere lingual lying: one tongue was not enough for all the business he had on hand. He acted lies as well. Indeed, sometimes his very silence was a lie.

William Shakespeare, As you like it, Act 3, scene 5; Rosalind says to Phebe:

But Mistris, know your selfe, downe on your knees

And thanke heauen, fasting, for a good mans loue;

For I must tell you friendly in your eare,

Sell when you can, you are not for all markets:

Cry the man mercy, loue him, take his offer,

Foule is most foule, being foule to be a scoffer.T.S. Eliot, Choruses from 'The Rock' VI:

24 But the man that is will shadow

25 The man that pretends to be.

26 And the Son of Man was not crucified once for all,

27 The blood of the martyrs not shed once for all,

28 The lives of the Saints not given once for all:

29 But the Son of Man is crucified always

30 And there shall be Martyrs and Saints.

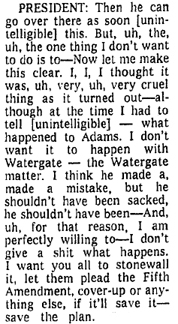

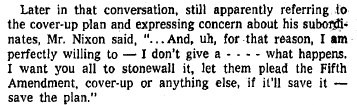

Since Kilpatrick may regard Shakespeare as out of date, and Melville as an untrustworthy Massachusetts liberal, I'll cite an example from a recent source with politically appropriate credentials:

In a sign of the difficulties Mr. Gingrich could face from other Republicans, however, Representative Tom DeLay, the House Majority Whip, immediately denounced the fund. ''Giving the I.M.F. more money is not a panacea for all the troubles that bedevil the Asian economy,'' he said. ''In fact, in many instances, the I.M.F is the problem, not the solution.'' [NYT, "Gingrich Clarifies G.O.P. Stands on Trade", by Alison Mitchell, June 26, 1998]

Or if The Hammer's recent corruption problems retrospectively disqualify him, how about the commissioner of baseball?

"There's no sense kidding ourselves about the ballparks,'' Selig said. "They've been great for the game, but they're not a panacea for all our ills.'' [Houston Chronicle, "Baseball attendance flagging for several reasons", by Richard Justice, 4/16/2003]

Or if politial outlook doesn't matter, let's move a few degrees to the left for a quote from Clyde Prestowitz:

Clyde Prestowitz, whose 1988 book, "Trading Places,'' predicted that Japan's government-business partnership would allow it to dominate high technology at America's expense, now declares that "the Japanese model was a fantastic catch-up model, but it was not a model for all seasons.'' He has taken to denouncing crony capitalism and sternly lecturing Japan on the need for fundamental reform. [Paul Krugman, [NYT, "Predicting doom in Asia's 'miracle' economies", by Paul Krugman, 5/5/1998]

In fact, after a modest amount of searching, I haven't come across a single published example where a competent writer of English follows Kilpatrick's theory of semantic interpretation. There must be some out there -- if you can find one, please let me know.

What led Kilpatrick to open his column so confidently with such a spectacularly wrong assertion about how the English language works? I won't speculate about his psychology, and I don't know about possible precursors in the prescriptivist literature for this particular piece of weird semantics. But my impression is that artificial rules about usage often start when a half-educated commentator with more self-confidence than insight, and with no respect for either demotic or elite traditions, decides that some common practice is inefficient or illogical. Why such pronouncements occasionally gain widespread acceptance is a question that could be the subject of several dissertations in intellectual history or social psychology. My own guess, FWIW, is that more insight will come from the natural history of religion than from rational choice theory.

This puzzle goes beyond the distinction that Eugene Volokh pointed out several years ago ("The Language Police", 1/26/2003):

Language defined by changing usage is what some call a "grown order" -- a judgment formed by millions of people, based on their senses of what is convenient and comfortable for them. (Free market economic decisions are another classic example of something that's mostly a grown order.) Linguistic prescriptivism (dictionarymakers recording what they think should be the usage, not what is the usage), is a "made order" -- a judgment of a small group of people selected for the purpose of rendering their judgment. Made orders are sometimes useful, for instance in the setting of technical standards. But as to language, I think the grown order approach is far more likely to yield a language that is genuinely responsive to users' needs than the made order approach.

In the first place, we're not talking about changing patterns of usage here -- as far as I can tell, Kilpatrick is not only wrong about contemporary English, he's wrong about Shakespeare and everyone in between. Nor does he claim that he's talking about a change that should be resisted. And in the second place, this is nothing like an ISO committee setting up a technical standard, it's one isolated individual, with no particular standing, laying down the law about how things ought to be, while pretending that his irrational prejudice is a foundational principle of grammar. In commentary on Eugene Volokh's post Neal Whitman's brother Glen observed that

The linguistic prescriptivists are analogous to the managers of a firm who, upon observing a new competitor that claims to make a better mousetrap, stubbornly insist that the old-fashioned mousetrap is superior. And maybe they’re right; the real test is in the mousetrap-buying choices of consumers. Likewise, in language, the test of the prescriptivists’ prescriptions is their staying power.

But presciptivists -- like Kilpatrick in this case -- often claim the support of logic rather than tradition. In this context, most linguists are not really either "prescriptive" or "descriptive" -- we try to evaluate claims about tradition, contemporary usage and logic in an honest and realistic way. We often wind up debunking the false claims of those peddling dubious linguistic prescriptions, but we're just as happy to debunk false descriptive claims. And of course we're happiest to join in advancing the understanding of how (and why) speech and language work, rather than the essentially negative enterprise of debunking nonsense of any sort.

I can't resist ending with a small personal note. Neal observes that the only way he can get Kilpatrick's favored reading for "Mass transit [is] not an option for all drivers" is to imagine saying it "with a seriously high pitch on all drivers". I believe that this is a reference to a phenomenon that Ivan Sag and I discussed, under the name of the "contradiction contour", in one of my first published linguistics papers: Mark Liberman and Ivan Sag, "Prosodic form and discourse function", CLS 10, 416-27 (1974). The version of this work that we presented at the annual meeting of the Chicago Linguistics Society may well have been the first scholarly paper ever performed with kazoo accompaniment -- in order to show how effective pitch contours can sometimes be in conveying meaning in English, we acted out some little skits in which Ivan's side of the conversation was performed on the kazoo. And we didn't debunk anything, though we did respectfully disagree with Ray Jackendoff about how to explain the effects of intonation on semantic scope. But all that belongs in another post.

[I should also mention that Eugene Volokh was mistaken about how most dictionary-makers see their role, when he wrote that they "[record] what they think should be the usage, not what is the usage". While lexicographers try to distinguish older usage from recent usage, and standard usage from dialect usage, and formal usage from informal usage, they're definitely in the business of describing rather than legislating. As a result, Robert Hartwell Fiske, in his screed The Dictionary of Disagreeable English, calls them "laxicographers". ]

July 28, 2006

X as the Y of Z

Recently, a reader alerted us to an incipient snowclone in the speeches and writings of Rees Lloyd:

(link) "The ACLU has lost all moorings and common sense and rationality and proportionality," he said. "It's become the Taliban of American liberal secularism.

(link) “Today, I am literally ashamed, ashamed that [the ACLU] has become the Taliban of American liberal secularism, wiping our history clean."

(link) "... the ACLU, which I believe has become, by its fanaticism, the Taliban of American secular totalitarianism.”

(link) ... the ACLU is now so fanatic and loosed from common sense that it has become the Taliban of liberal secularism ...

The idea of X as the Taliban of Y has been more widely used:

(link) "The Taliban of Modern Market Capitalism: Fear the accountants as much as the terrorists"

(link) I heard my denomination, the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod, described as "The Taliban of American Christianity" the other day.

(link) "If allowed to, Hezbollah could easily become the Taliban of Lebanon."

And sometimes the group compared to the Taliban are put in the of-phrase:

(link) Michael Moore and Al Franken are very proud that you and the taliban of liberal loonies are out making fools of themselves.

(link) In jumping into the Schiavo case, the Republicans are simply once again engaging in crass pandering to the Taliban of the religious right...

But the Taliban metaphor is not yet all that frequent, and in any case, it's a particular instantiation of a more general and much commoner meta-snowclone, which starts from a correspondence of the form A:B::C:D, where A and B are famous and evocative of some desired properties and relationships, and then transfers those properties and relationships to C in the context D, with a phrase like "C is the A of D". One of the commonest of these correspondences sets up George Washington and the establishment of the United States of America as the A:B pattern --

(link) In meetings, Deputy Undersecretary of Defense William Luti described him [Ahmed Chalabi] as the "George Washington of Iraq."

(link) Ali Al-Sistani: The George Washington of Iraq?

(link) He is called El Liberator (The Liberator) and the "George Washington of South America."

(link) ...it is probably only Nelson Mandela whose charisma, role, and accomplishments give him some claim to be the George Washington of his country

(link) The files contain an array of his edgy political positions, including his statement in Philadelphia that "Ho Chi Minh is the George Washington of Vietnam."

(link) Well, it happened, though, to the George Washington of Chile, Augusto Pinochet, the man who kicked the Reds out of Chile.

Similar phrases involving other founding (or at least epitomizing) fathers and mothers are common:

Price is truly "the Charles Darwin of nutrition".

Andrew Leonard is the Charles Darwin of bots...

Loch Eggers is the Charles Darwin of surfing.

...[Stilgoe] is the Charles Darwin of real estate, utility and transportation development...

Geoffrey Moore is both the Carl Linnaeus and the Charles Darwin of business and markets.

One writer referred to Breathnach as the "Isaac Newton of the Simplicity Movement."

A professor of philosophy from the University of Texas says, "William Dembski is the Isaac Newton of information theory."

Griffith, for good reason, is considered the Isaac Newton of filmmaking...

Arguably the most brilliant thinker of ancient China, and certainly the most systematic, he [Xunzi] has been called "The Aristotle of the East."

Scott McCloud, known as the "Aristotle of comics", writes that ...

Could Kerry be the 'Hitler of the Unborn'?

Saddam Hussein is the Adolf Hitler of the 1990's.

Elijah Muhammad is the Adolf Hitler of the black man.

Tila Tequila is the Adolf Hitler of culture.

Nancy G. Brinker calls herself ''the Carrie Nation of breast cancer.''

And the revolutionary was a woman oft hailed as a pioneer for women’s rights, the Carrie Nation of contraception, Margaret Sanger.

Ishimoto Shizue: the Margaret Sanger of Japan.

Marie Stopes, by the way, was the Margaret Sanger of England...

And there can be correspondences that don't involve people at all:

(link) Patents have become the nuclear stockpiling of the software industry.

[Update -- James Callan wrote in with links to his posts on "X is the Saudia Arabia of Y" ("I've discovered a snowclone", 7/13/2006), and "X is the Seattle of Y" ("The Things We Learn from Google", 7/20/2006).

And Benjamin Zimmer wrote:

This reminds me of an essay by Douglas Hofstadter, "Analogies and Roles in Human and Machine Thinking" (Sci. Am., Sep. 1981, reprinted in Metamagical Themas, 1985), where he considers what it means to call Denis Thatcher "the First Lady of Britain" or "the Nancy Reagan of Britain".

Searchable Metamagical Themas links:

http://www.amazon.com/gp/reader/0465045669/

http://books.google.com/books?id=o8jzWF7rD6oC

]

July 27, 2006

Stupid self-defeating warning label nonsense

I have been, for many years, a student of the language found in the stupid warning labels that grace increasing numbers of products in this increasingly litigious society. I have written before about the ultimate arch-warning that said "Do not misuse." But that one is rather like the sign Mark was once asked to make, saying that those who are not authorized are not authorized, or the "Do not use in the shower" label on Susanne Goldmann's hair dryer, or the warning that Peter-Arno Coppen saw quoted from a bike manual (in the excellent Dutch language magazine Onze Taal) to the effect that "Removing the wheel can influence the performance of the bicycle", or the astonishing sign that Barbara Phillips Long saw in an elementary school in Ithaca, N.Y., that said "Do not use elevator when no one is in building": cases like this may seem intuitively unnecessary, but ithey certainly imply directives that absolutely everyone is well advised, even obliged, to agree with and obey. However, I have recently been noticing warning labels that are impossible to obey without ruining the usefulness either of the label or of what it is attached to.

Just yesterday I received from some music club a sheet of stick-on security labels saying "This CD is the property of Geoffrey K. Pullum", and the sheet also carried a warning: "Do not affix directly to CD." Think about that. They have made me some free labels to mark my CDs as my personal property and warned me not to put them on them. (Yes, I know I could put them on the boxes. It would be great to be confident that those empty boxes would always be returned to me.)

And today, as I approached an automatic sliding door at an Office Max store that opened in response to a motion detector set to activate fairly close in, I noticed a bold sign on it saying, "Automatic door — Keep clear." Are people actually thinking about the sentences they put on such things? Or do they just (unlike Mark) make whatever signs they are told to make, no matter how ridiculous the assignment?

Just two more things about warning labels and then I promise I'll shut up. I know you want me to, but just two things. They aren't anything to do with the theme of this post, about language that clearly and necessarily defeats its own purpose (like "I am not moving my lips"); I just want to say these things and then that'll be that, OK?

1. Just once, I would love to use a stepladder that did not bear a label warning me not to treat its top step as a step. Just make the thing robust and leave it to me how high I want to go.

2. I still think the all-time most insane warning message I ever saw on anything anywhere was the message on a windshield-size folding cardboard sunscreen that I bought. (Let me just explain to residents of the Falkland Islands that the idea is to block out the rays of the sun from the front of your car while it is parked, so you don't burn your fingers on the steering wheel when you come back after a few hours in the hot California sunshine and try to drive off. You must understand that — while the weather is gorgeous in Santa Cruz — earlier this week in the town of Bradley, an hour or two to the south of here, the temperature hit 120°F in the shade.) On the rear (inside) surface of the opaque cardboard it said: Do not drive with shield in place.

Unlike no other

The Marketplace radio show yesterday ("Faith Nights get the call", 7/26/2006) interviewed Brent High, CEO of Third Coast Sports, a company that produces "Faith Nights" at baseball games and other sporting events, and recorded him saying

"It is an opportunity -- unlike no other -- to introduce people to the church in an environment that is not churchy."

This seems to a clear example of overnegation, like "No head injury is too trivial to ignore", or "This is sure to be a killer tournament, don't fail to miss it!" It's obvious what Mr. High meant, but what he said seems literally to mean the opposite. If this opportunity were "like no other (opportunity)", or "unlike any other (opportunity)", it would be a uniquely good (or perhaps uniquely bad) opportunity. But if this opportunity is "unlike no other (opportunity)", then all opportunities are the same, and you might as well pass out tracts on a random streetcorner as set up a Faith Night at Turner Field. At least, that's how it works if two negatives make a positive.

Barbara Wallraff considered this expression in her Word Court feature back in 2003. Her judgment, rendered in response to a reader who found the expression confusing, was:

I looked for examples of “unlike no other” in print and, to my surprise, found them. “Unlike no other” is a double negative. If that’s what people are saying, you’re not confused—they are.

Barbara may be right that some of these are examples of negative concord, the "It ain't no cat can't get in no coop" construction persisting in the vernacular from the old grammar of negation in English, before our linguistic ancestors got mixed up by those French invaders. The wikipedia entry on double negatives quotes a song lyric

- Well, I ain't never done nothing to nobody.

- I ain't never got nothing from nobody, no time.

- And, until I get something from somebody sometime,

- I don't intend to do nothing for nobody, no time.

and the dialect expression "I am not never going to do nowt no more for thee." Linguists generally treat these multiple negations as a form of agreement or feature spreading, which is obligatory in the standard versions of many languages. Examples from the wikipedia article include Serbian:

Niko nikada nigde ništa nije uradio, literally Nobody never nowhere nothing did not do, meaning "Nobody ever did anything anywhere."

Czech:

Nikdo nic nevyhrál, literally Nobody didn't win nothing, meaning "Nobody won anything."

Hungarian:

Soha sehol ne mondj el semmit senkinek, literally Never nowhere don't tell no one about nothing, meaning "Don't ever, anywhere tell anyone about anything."

Classical Greek:

μὴ θορυβήσῃ μηδείς, literally Do not let no one raise an uproar, meaning "Let no one raise an uproar."

Afrikaans:

Dis (=Dit is) nie so moeilik om Afrikaans te leer nie, literally It's not so difficult to not learn Afrikaans, meaning "It's not so difficult to learn Afrikaans."

(There are a lot of interesting issues about how far various sorts of negation spread or don't spread in different languages, but that's a matter for another post.)

Some of the "unlike no other" examples in English might be related to the vernacular pattern of negative concord. Here's a possible case from an AP story about NASCAR ("Busch Turns the Corner with a Surge of Success", 7/16/2006):

Roush said: “Well, it’s been a great ride with Mark Martin for 600 starts now. He’s brought intensity, enthusiasm, great driving ability and integrity to the driver’s seat, unlike no other driver that I can recall.”

I've got no idea how Jack Roush talks when he gets comfortable, but it's possible that he's fine with saying things like "he ain't like no other driver", and in that case, the extra "no" in his quote might just be negative concord. But there are other examples, in more formal contexts, that I'm pretty sure are just ordinary overnegation, where people have just gotten confused about how many negatives are really needed to make their point. Here's an example from the presumably well-edited O'Reilly Safari site for David A. Karp's "eBay Hacks, 2nd Edition":

Unlike no other book, eBay Hacks, 2nd Edition also provides insight into the social aspects of the eBay community, with diplomatic tools to help to get what you want with the least hassle and risk of negative feedback.

That's not a dialect form or an idiom, it's just a mistake. Or is it? Could (some) overnegations in English be a formal residue of a stubborn hankering for negative concord? On this view, confusion about the semantic complexities of multiple negation plays the role of a sleepy gatekeeper, allowing vernacular impulses to sneak into the standard language.

July 26, 2006

The Perils of Transliteration

Just now on Jeopardy the question was "Who is Park Chung-Hee?", the President of South Korea from 1961 until his assassination in 1979. Alex Trebek pronounced it incorrectly, with an r, like the English word "park". Actually, the family name of 朴正熙 (박정희) is pronounced [pak], roughly like English "bock". In the current official South Korean romanization it is rendered Bak. Trebek's error is as much Park's fault for choosing a non-standard romanization as Trebek's. I suspect that the romanization with an r, which is pretty common, was based on an r-less dialect of English, probably British, and was meant to prevent it from being interpreted as [æ], as in "back" and "Mac".

The moan of the dunes

Who you gonna believe, the NYT science section or your own lyin' ears? Reporting on some very interesting work by Stéphane Douady and others on the physics of "singing sands", Kenneth Chang ( "Secrets of the Singing Sand Dunes", July 25, 2006) can't resist a musical lede:

Who you gonna believe, the NYT science section or your own lyin' ears? Reporting on some very interesting work by Stéphane Douady and others on the physics of "singing sands", Kenneth Chang ( "Secrets of the Singing Sand Dunes", July 25, 2006) can't resist a musical lede:

The dunes at Sand Mountain in Nevada sing a note of low C, two octaves below middle C. In the desert of Mar de Dunas in Chile, the dunes sing slightly higher, an F, while the sands of Ghord Lahmar in Morocco are higher yet, a G sharp.

Unfortunately for Chang's credibility, he (or more likely one of his editors) chose to accompany the article by a lovely video clip (identified as being "sounds .. 'played' on a singing dune located in the Atacama Desert in Chile") providing singing-sand sounds that are more like moans than sung notes, each sound clearly spanning a fairly wide range of pitches.

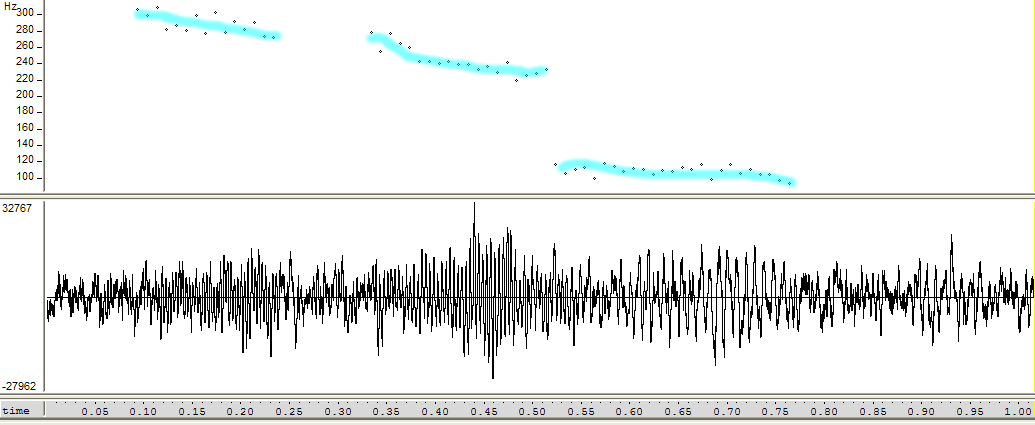

Here's a graphical representation of one example [audio clip], with an automatically-generated pitch track on which I've manually sketched some trend lines for clarity:

This particular sound sequence, produced by one sweep of the dune-player's hand, has an initial segment that falls from about 308 Hz (a bit below the D# just above middle C) to about 226 Hz (half-way between A and A# below middle C), followed by a period-doubling (i.e. pitch halving) and a somewhat more level-pitched segment ending around 103 Hz (just below G#, in terms of musical pitch-classes relative to A=440).

In other words, this moan of the dunes starts just above middle C, falls by a tritone (six semitones), and then drops by an octave to end about an octave and a fifth lower.

Even if you have perfect pitch (and I certainly don't), you probably can't hear the intervals involved accurately, since people with perfect pitch don't perceive the pitch of such glissandi very clearly -- or at least that's what a couple of them have told me. However, anybody with normal hearing and pitch perception can tell by listening to this clip that the dune's sound, in this case, is not well characterized as a "note", but rather is a falling glissando spanning a considerable range.

This is a small nit to pick, in an interesting and well-written article about a nice piece of research. I've posted about it not because I like to play "gotcha" with journalists -- in fact I don't enjoy it at all -- but because this is such a clear example of such a common problem. More often than not, the popular presentations of scientific or technological results are strikingly at variance with features of the results themselves, features that are obvious to anyone who knows anything about the subject or who looks at the primary sources with a bit of common sense. Sometimes this is entirely the fault of the scientists and engineers, and their PR representatives often contribute as well, but in the end, the largest share of guilt belongs to the reporter and editor, whether they juice up the story themselves or credulously accept the juice from another source. And in this internet age, it's increasingly easy for readers to check things out, and to blog what they find.

There's not a lot of extra "juice" in this case -- just Chang's choice to lead with a comparison of deserts as if they were organ pipes. We're not talking about a flat-out fabrication, like the stuff about how email lowers IQ more than pot and men are emotional children, or a preposterous exaggeration, like the idea that Germans are grumpy because of umlauts. In this case, it's just an attempt to grap the reader's interest with the cute idea that deserts have characteristic pitches, before getting to the physics part. And Chang's lede is not totally invented, anyhow, since Douady's article suggests that the pitch of the dune sounds depends on the statistics of grain sizes (which may be different for different deserts), and offers some lab results citing different pitches for sand samples from different locations. However, the video clip accompanying the article makes it clear that at least some of the dune sounds, in their natural state, are not stable pitches at all. So Chang's lead, though attractive, is directly contradicted by the evidence in his sidebar video.

Well, actually, Chang compounds the problem when he tries to explain, later in the opening paragraph, that

While the songs are steady in frequency, the dunes do not have perfect pitch. At Sand Mountain, for example, dunes can sing slightly different notes at different times, from B to C sharp. [emphasis added]

Um, Kenneth, your own video sidebar makes it clear that the "songs" are NOT necessarily "steady in frequency". Isn't that a little embarrassing?

[The scientific paper is S. Douady, A. Manning, P. Hersen, H. Elbelrhiti, S. Protiere, A. Daerr, B. Kabbachi, "The song of the dunes as a self-synchronized instrument", unpublished ms. 12/2004, revised 1/2006, to appear in Physical Review Letters (?). More info about moaning dunes is available on Douady's web site.]

[There is no truth to the rumor this story is the oneiric source of the question famously asked by Dan Rather's assailant in 1986. It's for that reason that I resisted the temptation to title this post "What's the frequency, Kenneth?"]

[Update -- Kenneth Chang emailed:

Geez, if you're going to pose questions/insults, you really should provide some straightfoward way for someone to reply.

From the abstract of the paper: "Since Marco Polo (1) it has been known that some sand dunes have the peculiar ability of emitting a loud sound with a well defined frequency, sometimes for several minutes."

The notes are taken from Table 1, which I hope I didn't mess up.

The discrepancy arises, I believe (from reading the paper), because you can generate different notes by changing the speed you push the sand, like in the video (and Table 2). There are also overtones. In naturally occurring avalanches, there is one characteristic speed and hence one characteristic note.

So... we should have put a better explanation accompanying the Web video, It's unfortunately impossible to include all these nuances in a 300-word article.

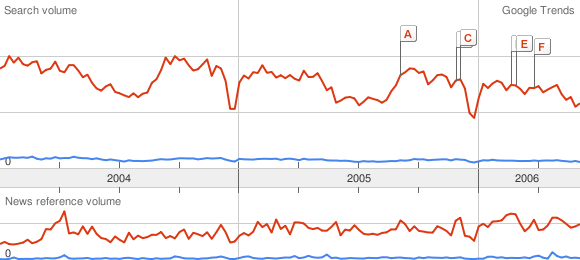

It's absolutely true that the abstract of the Douady et al. paper suggests that the pitches are typically level, and that the information about the particular association between deserts and pitches comes from Table 1 in the Douady et al. paper:

This is what I meant by alluding in a general way to the source of the idea in the cited paper, but I should have been more precise. I could quibble a tiny bit with Chang's translation from Hz to musical pitch-classes, but what's a semi-tone or so among friends? And the plain fact is that the implication of a fixed connection with between deserts and pitches via characteristic sand-grain sizes is suggested by this part of the paper that Chang is reporting on. It's also very plausible that naturally-occurring avalanches usually involve stable velocities and therefore stable pitches.

On this basis, I owe Chang an apology for any implication that he was responsible for the idea of deserts being musically tuned: it comes pretty directly from the Douady paper.

The figure that helps explain why the sounds in the video clip are not steady pitches is reproduced below:

This (their Figure 2) shows "Frequency emitted by pushed (sheared) sand, measured in laboratory experiment, as a function of two laboratory control parameters, height of mass of sand, H, and velocity of pushing blade, V." See the paper for further details -- but the figure clearly shows the same sand, from the same desert, emitting a range of frequencies spanning more than three octaves. Presumably, as Chang suggests in his note, the velocity of the dune-player's hand in the video is standing in for the velocity of the blade, and the velocity contour of his gestures is produces a corresponding pitch contour.

So Douady and his co-authors are to arguably to blame for publishing a misleading Table 1, without a clear explanation of the fact that the implied close connection among deserts, grain sizes and (level) pitches is not generally true in the laboratory, and may be true in the field only under certain circumstances, and in particular isn't true in some of their own field examples. We can't blame Kenneth Chang (who is clearly an excellent science writer in general, and to be commended for bringing an interesting piece of work to general attention) for anything worse than a minor failure to read (and listen) critically -- and it's plausible in fact that he understood the whole situation from the beginning, but simply couldn't fit the whole discussion within the rigid article-length limit that he had to work with.

I'm glad I'm a blogger! It's a lot easier to write more than to write less. ]

July 25, 2006

English under siege in Pennsylvania

More than a third of all Pennsylvanians are native speakers of a language other than English -- and many of them have not even tried to learn English since immigrating, or at least prefer to carry out their daily lives in another language, living together in neighborhoods where their native language dominates. Some people worry that the majority status of English is critically endangered. 25 years ago, a major political figure warned that these "aliens ... will never adopt our language or customs, any more than they can acquire our complexion", and so far, his prediction seems to be right on the money. But wait -- the date is 1776, not 2006, and the language contending with English is not Spanish, it's German, and the major political figure who warned about the "aliens" who "swarm into our Settlements, and by herding together establish their Language and Manners to the Exclusion of ours" is Benjamin Franklin.

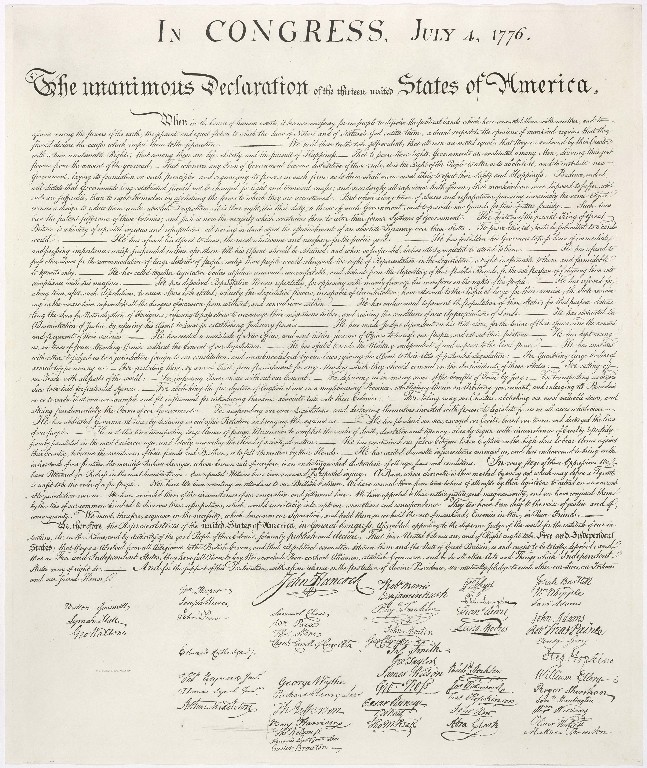

The first newspaper announcement of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence was published in German, on Friday, July 5, 1776, in the Pennsylvanischer Staatsbote. On Tuesday, July 9, the same paper devoted its front page to a German translation of the declaration. The picture below is from a web exhibit by the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin:

Linguistic sweetness and light didn't always prevail among the founding fathers. As I mentioned, in 1751 Benjamin Franklin said some things about German immigrants that would put him on the ethnocentric fringe of today's debate. Curiously, in 1732 Franklin had published a German-language newspaper -- though it only lasted for two issues, perhaps because he didn't have a Fraktur typeface, and so had to print his German material in his usual roman-letter Caslon Antiqua. In 1735, Christopher Sauer began publishing in German with the familiar Fraktur letters, and had considerable success with a German-language almanac that had a circulation as high as 10,000, and thus was in implicit linguistic competition with Franklin's English one. Today's readers may be interested to know that Sauer and his newspaper, published since 1739 in Germantown, were socially and religiously conservative supporters of the Penn family, and thus "a thorn in the flesh of any progressive politician in the colonies", especially Franklin.

In 1762 Heinrich Miller (who had earlier worked for Franklin) began publishing the Wöchentliche Philadelphische Staatsbote. Miller's politics were much more to Franklin's taste:

It is Henrich Miller, who gave the German population of the Middle Colonies the opportunity to learn about and to participate in the various political controversies that would gradually lead to independence. He printed in German Jonathan Dickinson's and Joseph Galloway's speeches in Assembly on the change of government in Pennsylvania in 1764, he printed a German version of Benjamin Franklin's interview before the House of Commons concerning the Repeal of the Stamp Act in 1766, and from 1774 on he practically served as official German printer for the First Continental Congress by repeatedly publishing its minutes and votes in German. ... Christopher Sauer in his "Germantowner Zeitung" had taken side against Britain during the Stamp-Act Crisis, but when the course of events led more and more towards armed revolution he had to make amends to the pacifistic convictions of the Brethren and to stay free from radical positions in his publications. This led later to Sauer's being accused as a loyalist and Congress put him under orders to abstain from printing and his whole property was confiscated and put up for auction for the public benefit. His successor, Christopher Sauer III, then actually joined the British side and served as printer to the occupation army in Philadelphia and New York.

In 1776, the difference in political allegation between the two established German presses became evident: while Sauer printed a decisive call for peace and to abstain from armed resistance issued by the Quaker community, Miller printed a pro-congressional pamphlet directed at the German inhabitants under the title "Der Alarm", the Minutes of the Constitutional Convention of Pennsylvania and the Regulations for the Pennsylvania Militia in German.

A number of earlier Language Log posts have focused on America's varied linguistic landscape during its first couple of hundred years. This was never a linguistic garden of Eden -- whatever you think prelapsarian social norms should be like -- but viewed in the light of history, the current anxiety over linguistic identity seems exaggerated. By most measures, English in America seems to be stronger than it's ever been.

"The world is upside down" (2/24/2004)

"When smart people get really stupid ideas" (5/2/2204)

"Palatine Boors and their Maryland descendents" (5/14/2004)

"Mere knowledge of the German language cannot reasonably be considered harmful" (5/21/2004)

"Nativism clings to life at 100 or 101" (6/24/2004)

"The secret Netherlanders among us" (7/2/2004)

"The multilingual anthem" (4/29/2006)

And you may be interested in this essay by Dennis Baron on "The legendary English-only vote of 1795". More on the same topic is found in a chapter "German or English?", from "The German Americans: An Ethnic Experience, by Willi Paul Adams (originally Die Deutschen im Schmelztiegel der USA: Erfahrungen im grössten Einwanderungsland der Europäer).

PowerGenitalia and PenisLand

Concerning those ambiguously analyzable web site names mentioned this weekend on NPR's "Wait Wait Don't Tell Me" (and I know you were waiting for Language Log to comment on this clearly linguistic story), it does appear to be the case that there is an Italian battery company called Powergen Italia (no relation to the British company called Powergen), and it seems they really did once set up a website with the URL www.powergenitalia.com.

It was taken down some years ago (the company now uses www.batterychargerpowergen.it), but the WayBack Machine keeps an archived copy in this location (just click Cancel if it asks for a password). It's not just a hoax site, as claimed at this page (the commenter below seems to be correct). And they actually spell their name as "Powergenitalia s.r.l."

The story seems to be a thoroughly old one; the above snapshot of the days of PowerGenItalia.com is from 2001. No word yet on why it suddenly resurfaced this week on Wait Wait.

And the other case, Pen Island really is a company selling customized pens, and really does have a current web site called www.penisland.com. They claim to have had at least a certain amount of trouble with rude spam sent in their name, and with people setting up sites with similar names for rather more penis-related purposes. See this page for some further discussion.

Don't forget, concatenation of letter strings can get you into things you didn't want to get into: sometimes x(yz) and (xy)z are non-equivalent but both yield xyz when the spaces or brackets are erased. Always get your proposed URL analyzed for double entendres by fully qualified linguists before setting up your site. Just call the main switchboard at Language Log Plaza and ask for the Uniform Resource Locator Morphological Analysis Division.

Thanks to Brendan McGuigan and Stephen K. Benjamin for research assistance.

July 24, 2006

Two languages short of bilingual

OK, I'm not quite so speechless anymore after reading Bill Poser and Mark Liberman on the Bogota iced coffee ad shock horror scandal probe. Apostrophe use in English is tough, I admit that; learning it takes a bit of work. But public servants speaking out on language issues — especially those who think that Spanish-speaking immigrants have a duty to learn English before turning up for work at the factory or the farm — should be the first to tackle that work. How about a campaign to ensure that politicians who try and soak up right-wing and anti-immigrant votes by participating in language bigotry should at least get their apostrophe placements right? ‘E-Mail me,’ says Mayor Steve Lonegan, the man organizing a McDonald's boycott (or "McDonalds boycott" as he would say) in his "Mayors Message": ‘Email me at mayor@bogotaonline.org’. So let's do that (or "lets do that", as the Mayor would say). Let's all email him with a brief summary of the rules for use of the apostrophe in genitive singulars and genitive plurals. And perhaps subject-verb agreement as well; Fernando Pereira (a Portuguese-speaking immigrant, but he works hard and learned English before turning up to work at the University of Pennsylvania) has pointed out to me that the Star-Ledger story quotes Lonegan as saying: ‘The true things that bind us together as neighbors and community is our belief in the American flag and our common language.’ This man needs language assistance. Especially given his job. Being monolingually literate in Standard English is the normal baseline for politicians. Lonegan falls below this; he's two languages short of being bilingual.

As Mark Liberman reminds me, our president's stirring words should be our guide here:

We need to challenge the soft bigotry of low expectations. If you have low expectations, you're going to get lousy results. [Applause.] We must not tolerate a system that gives up on people."

Language Log does not give up on people. Not even politicians. Our credo is no politician left behind.

Mensaje de los alcaldes [sic]

Because Geoff Pullum and Bill Poser were preoccupied with the problem of characterizing Steve Lonegan, the mayor of Bogota, NJ, who has led the recent objections to Spanish-language McDonald's ads, they failed to tell you something important about the Borough of Bogota's web site. I don't mean the weekend truck rental service, though that is way cool. I'm referring to the helpful little BabelFish panel in the lower left corner of every borough web page. This includes the "Mayors Message" [sic], which is therefore available in (a reasonable approximation to) Chinese, German, Japanese, Korean, French, Italian, Portuguese, and (last but not least) Spanish. (The order is a bit odd -- at first I thought it was alphabetic, but French and Italian are out of sequence.)

As a result, the Borough's own web site is far more complicit than the contested McDonald's billboard in helping furriners to get by without learning English. The McDonald's billboard only informs linguist miscreants that "Un frente helado se aproxima. Nuevo café helado." When they actually get in line for that café helado, they're going to have to figure out that it's on the menu as "iced coffee". But with one click on the eBogota web site, we learn that "¡Si usted vive en Bogotá, Nuevo-Jersey usted es vivo en una ciudad que sepa que una parte grande del futuro está haciendo vida conveniente y fácil! Somos re-engineering la manera que nuestra ciudad hace negocio, estamos haciendo un esfuerzo de tener Bogotá en línea y abierto para el negocio 24 x 7." You can already "pre-register" your gato or perro -- and apparently soon you'll be able to transact all your business with the borough on line, in convenient Spanish translation!

Anyhow, there's another small linguistic point here. Because Mayor Lonegan left the apostrophe out of his title, the Fish dutifully renders it as "Mensaje de los alcaldes" -- "Message of the mayors". I could care less about apostrophes, myself, but given the importance of setting a good example for immigrants, I'm tempted to turn this one over to Lynne Truss.

[Update -- Steve from Language Hat writes:Did you notice that the Spanish version of the Bogota website calls it "Bogotá"? That's pretty funny, because the pronunciation of the NJ town is stressed on the penultimate syllable (as a MetaFilter commenter put it, it rhymes with Abe Vigoda). Furthermore, according to Kelsie Harder's Illustrated Dictionary of Place Names, the town name has nothing to do with the Colombian city but is "from the name of a Dutch family of early settlers, Bogert." (Oddly, the extremely detailed historical section of the Bogota website -- http://www.bogota.nj.us/history/default.asp -- doesn't explain this, saying only "It was at this time that 'Bogota' was beginning to be used as the name of our area of Ridgefield rather than 'Winckelman,'" but the Bogert family does feature prominently in the history.)

Curiouser and curiouser. It's typical of those sly and stubborn Dutch immigrants to try to disguise their linguistic atavisms as Spanish! ]

Another Jackass of the Week

Since Geoff is tongue-tied, I'll help him out. Mayor Steve Lonegan of Bogota, New Jersey is our new Jackass of the Week. He thinks that an ad for iced coffee in Spanish sends the message that Spanish-speaking immigrants don't need to learn English. Hunh? People surrounded by English-language media, who for the most part need to use English at work, at school, and in business, including when they work or eat at McDonalds, are going to conclude that they needn't bother learning English because the occasional ad is in Spanish? And how is advertising in Spanish "divisive"? Surely whining about other people's languages is what is divisive. Warren Meyer has aptly named the phenomenon whereby some people turn into blithering idiots on hearing Spanish Spanish Derangement Syndrome.

I think I'll stop by my local McDonalds tomorrow. Incidentally, according to this article, Bogota doesn't even have a McDonalds.

July 23, 2006

Iced coffee ad for Hispanics outrage

The mayor of Bogota, New Jersey, authorized by a 4 to 2 vote of the council, wrote to McDonald's to protest a billboard on which iced coffee was advertised in Spanish. He urges a boycott if McDonald's won't take the sign down (see story here). I ought to have an informed comment on this, but words fail me. I simply do not believe the excesses of the language bigots in this country sometimes.

Will Shortz sets impossible puzzle on NPR

Will Shortz's word puzzle for last week (on NPR's Weekend Edition Sunday) was to find a name from classical mythology that was, in spelling, a concatenation of English pronouns. And the problem was probably impossible. What's for sure is that the answer he gave was not correct.

The answer was supposed to be Theseus, the name being a concatenation of these and us. The latter for is indeed the accusative form of the pronoun lexeme we. But the former, these, is not a pronoun.

I'll be using the terminology of The Cambridge Grammar in explaining why, but this isn't some sort of terminological quibble: there really are pronouns in English, and they share certain very clear, sharp properties. And the word these is not one of them, no matter which system of terminology you prefer. The thing is that there are syntactic differences in behavior between the two classes of words.

These is the plural inflected form of the lexeme this, which is a determinative, specifically a member of the demonstrative subclass of determinatives (another subclass is the articles, the definite article the and the indefinite article in its two shapes an and a).

The lexeme this is one of the special determinatives (like some and most, but not the articles) that are permitted to function as simultaneously determiner and head of a noun phrase. (There are some subtleties to the argument; but see page 422 of The Cambridge Grammar for some crucial discussion.) So that's why a form of this can occur on its own where a noun phrase can occur (which is perhaps the root of the confusion): This is typical has a subject noun phrase consisting of only one word, which is both determiner and head of the subject noun phrase.

Here, very briefly, are four lines of evidence for arguing that these is a determinative, not a pronoun. The last one is particularly telling, I think.

1. Third-person pronouns do not co-occur in a noun phrase with a common noun the way determinatives do: the book is a (singular) noun phrase (and the is a determinative); *it book is not a noun phrase (and it is not a determinative). [It must be noted here that the pronouns we and you are special in that they have additional uses as determinatives, in phrases like we linguists or you boys; see page 374 of The Cambridge Grammar for discussion. But this is special to just those two lexemes. None of the 3rd person pronouns have second lives as determinatives in Standard English (notice, these is 3rd person); and none of the singular ones do; and none of the reflexive ones like yourself do; and so on. Don't be misled by How 'bout them apples? or them bones, them bones gonna walk around; those are from non-standard dialects where the shape of some items is different, and those dialects have a determinative with the form of them and the meaning of those. Tricky, isn't it?]

2. Pronouns do not in general allow modification by preceding quantifiers: *every it, *all they, etc., are not grammatical noun phrases.

3. Pronouns occur before the particle in verb-particle idioms, not after it: Don't even bring it up in conversation (with the pronoun before the particle up) is grammatical but *Don't even bring up it in conversation (with the pronoun following) is not.

4. A particularly salient point is that pronouns occur in what are known as confirmatory tags: compare Susan is clever, isn't she? (grammatical) with *Susan is clever, isn't Susan? (not grammatical).

Now, by all four of the tests these facts make available, these is a determinative, not a pronoun!

First, these books is a grammatical noun phrase (confirmation of determinative status).

Second, all this and all these are grammatical (disconfirmation of pronoun status).