August 31, 2006

Arabic T-Shirt Grammar

The grammatical controversy as to how to say "I am not a terrorist" in Arabic to which Ben Zimmer refers, is, I think, not so much about what the correct grammar is as what sort of Arabic to use. As I understand it (and Arabic is not exactly my best language), it is definitely the case that a noun such as "terrorist" should be in the accusative case when it is the predicate nominal in a negative predicate. This rule, however, is a rule of Classical Arabic: the modern colloquials do not have the three-way case distinction of Classical Arabic and therefore have no such rule. What the debate is really about, then, is whether T-shirt slogans should be in the classicizing "Modern Standard Arabic" or in a more colloquial variety.

Addendum: Readers with greater knowledge of Arabic than mine have explained that the issue of what is correct grammar and which variety of Arabic to use are intertwined because the verb lastu "I am not" is used only in Modern Standard Arabic. It is not found in any of the colloquial varieties. Therefore, if you use lastu you also need to put "terrorist" into the accusative case. If you don't use the accusative case of "terrorist", you must be writing in a colloquial variety of Arabic and will therefore use a different negative construction, one that does not use the verb form lastu.

Kahunas v. Cojones

The Editor at Blawg Review has noted an interesting usage on Kevin O'Keefe's blawg (or is it a meta-blawg?) Real Lawyers have Blogs. In a post under the title "New legal tabloid an idea long overdue", O'Keefe writes that:

It's going to take some big kahuna's to publish those cease and desist letters and demands for retractions. But they be some of the best posts.

O'Keefe probably meant to invoke the border-Spanish euphemism for manly assertiveness, "big cojones", rather than the surfing-derived term for boss or expert, "big kahuna". The Blawg Review suggests that this substitution is an eggcorn. It seems to me that the verdict is not clear -- perhaps O'Keefe is just confused about how to spell "cojones"; or maybe he's confused about what "kahuna" means; or maybe this was just a malapropism of the kind that afflicts all of us from time to time, when an unintended word comes out in place of one that sounds similar.

A brief Google search shows that O'Keefe is far from the first one to make the cojones → kahunas substitution:

You got some big kahunas taking on Pollux!

These guys must have some big kahunas to operate these trucks in these environments.

One of the areas is a very long uphill section where you have to have some big Kahunas to go all the way up over the hill (you can't see the other side) at full throttle and down into an off camber downhill left turn.

Took some big kahunas to actually go through with it, but it worked out well for them in the end.

The Roxio folks have some big kahunas calling it an "upgrade".

A big thankyou to WindWarrior cameraman Mark 'Willy' Williams who's got kahunas the size of coconuts to get out in the water with his camera and then get sailors to jump over him.

For some people, apparently, a Hawaiian word for "priest" has ended up as an English euphemism for "testicles".

Perhaps O'Keefe deserves to be memorialized in the eggcorn database. But what he really has to worry about is getting hacked up by Lynn Truss for that superfluous apostrophe.

[Update -- Ben Zimmer writes:

Note that since the 1980s "big kahuna" has meant, as HDAS defines it, "a large or important thing or person." I'd say there's at least some eggcornification going on here, since it's plausible to think that big kahunas are invested with big cojones.

kahuna n. [< Hawaiian 'priest or wise man']

1. a. Surfing. an expert surfer.—often constr. with big. [...]

b. Orig. Hawaii. an expert of any sort. [...]2. a large or important thing or person.—often constr. with big.

1987 E. Spencer Macho Man 177: I am a witness for those big Kahunas, the B-52's. 1991 N.Y. Newsday (Feb. 7) ("City Living") 83: To this big kahuna, all things tiki really are quite chic-y. 1993 Frasier (NBC-TV): This is for television! The big kahuna! 1996 L.A. Times (Nov. 4) A12: To surrender their critical thinking and personal autonomy to the will of the big kahuna.

]

[Update #2 -- Jim Gordon points out the blend {"big cahones"}. And then there's {"big kahones"}, {"big cohunas"}, {"big cujones"}, {}"big kohanes"}, and doubtless many others. ]

Cucumber cows

I've learned from Hugo Quené that late summer, which in English-language journalism is called the "silly season" and in German is called "Sommerloch" (= "summer hole"), is known as "komkommertijd" (= "cucumber time") in Dutch. That's the basis for the cucumber slices in this picture, which adorns an item on Noorderlog, the weblog of the Dutch science news site Noorderlicht, posted on August 29 under the title "Komkommerkoeien" (= "cucumber cows"). The cow part of the picture comes from Noorderlog's earlier post, "Koeiendialect" (= "Cow dialect"), which had credulously passed along the BBC's reproduction of a cheese company's press release.

I've learned from Hugo Quené that late summer, which in English-language journalism is called the "silly season" and in German is called "Sommerloch" (= "summer hole"), is known as "komkommertijd" (= "cucumber time") in Dutch. That's the basis for the cucumber slices in this picture, which adorns an item on Noorderlog, the weblog of the Dutch science news site Noorderlicht, posted on August 29 under the title "Komkommerkoeien" (= "cucumber cows"). The cow part of the picture comes from Noorderlog's earlier post, "Koeiendialect" (= "Cow dialect"), which had credulously passed along the BBC's reproduction of a cheese company's press release.

It seems that Hugo sent Noorderlicht a link to my post "It's always silly season in the (BBC) science section" (8/26/2006), and they found it persuasive enough to call in the staff photographer, slice up a cucumber and look around for a cow. (I like the visual reference to cucumber facials.) So far, the BBC has not updated its coverage of the cow dialect story, except to offer a link to a BBC Radio Five piece that compares and contrasts the moos of cows from Somerset, Essex, Norfolk, and the Midlands.

Memo to Ashley Highfield: ... oh, never mind.

[Update -- Jarek Weckwerth writes:

Re your post about the Dutch term for "silly season": in Polish, it's known as "sezon ogórkowy" ("cucumber season"). Just the other day, I was in a bar where they had a party to celebrate the end of the cucumber season, with heaps of cucumbers all over the place. Proved a good way to generate some interaction among the punters.

J

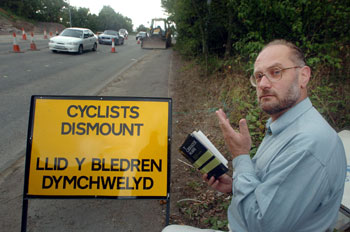

Arabic-ophobia

An addendum to Bill Poser's post about the fellow who couldn't fly out of JFK because he was wearing a T-shirt with an Arabic slogan... The wearer of the T-shirt was Raed Jarrar, the Iraqi Project Director for the human rights group Global Exchange, and the slogan in question was "We will not be silent" (لن نصمت), popular among opponents of U.S. policy in Iraq and elsewhere in the Middle East. There's a picture of Jarrar wearing the shirt here, and an image of a similar T-shirt accompanies this BBC report. Note that the shirt has both Arabic and English versions of the slogan on it, so it's not like the airline officials had no hints as to what the mysterious squiggles meant.

In protest of the incident, BoingBoing

reports, Tim

Murtaugh is selling a T-shirt that reads "I am not a terrorist" in

Arabic: انا لست إرهابي (ana lastu

irhaabi). There's been some nitpicking

over the grammar — some say it should properly be انا لست إرهابياً since irhaabi 'terrorist' ought to be in

the accusative after the verb lastu 'am not',

unless irhaabi is intended as an adjective ("I am not terroristic"?). A good effort, in

any case — Murtaugh even offers a female variant of the shirt.

In protest of the incident, BoingBoing

reports, Tim

Murtaugh is selling a T-shirt that reads "I am not a terrorist" in

Arabic: انا لست إرهابي (ana lastu

irhaabi). There's been some nitpicking

over the grammar — some say it should properly be انا لست إرهابياً since irhaabi 'terrorist' ought to be in

the accusative after the verb lastu 'am not',

unless irhaabi is intended as an adjective ("I am not terroristic"?). A good effort, in

any case — Murtaugh even offers a female variant of the shirt.

This all reminds me of another example of American anxiety in the presence of written Arabic, involving the Nobel Prize-winning Egyptian novelist Naguib Mahfouz, who died on Wednesday at the age of 94. As noted by Lameen Souag on his excellent blog Jabal al-Lughat, Edward Said tried to convince a New York publisher to put out English translations of Mahfouz's great Cairo Trilogy back in 1980 (before he won the Nobel). The publisher demurred, telling Said that "Arabic was a controversial language." Sadly, it remains controversial, at least at our nation's airports.

Terrorism and the magical power of words

According to press reports, a man wearing a T-shirt with an Arabic slogan on it was denied boarding on a flight out of Kennedy airport recently. One of the officials reportedly told him: "Going to an airport with a T-shirt in Arabic script is like going to a bank and wearing a T-shirt that says, `I'm a robber'". It isn't clear, apparently, whether the culprits were airline staff or TSA staff.

This raises concerns about freedom of speech, of course, and about the competence of the people in charge of airport security (hint: your better terrorists don't advertise their occupation), but there is also a linguistic curiosity here. What, exactly, did they think they were protecting against? The slogan was certainly not a weapon. If he were a terrorist, wearing the T-shirt would not have assisted him in his task. It's true that Arabs figure prominently in the terrorism game, so it may make sense to pay particular attention to Arabs, but if that were the point, they wouldn't have denied him boarding, they would just have selected him for extra scrutiny. It is remotely possible that they thought that he was so powerful and dangerous that even without any weapons he was a threat, but in that case they surely would not have allowed him to board once he covered up the T-shirt, which is what they did. Assuming that they weren't engaged in simple harassment, which is a possibility, the only sense that I can make of this is that the officials concerned attributed to the words some sort of magical power that could be contained by covering them up. There have been societies in which people held such beliefs, but I wasn't aware that the United States in the 21st century was among them.

August 30, 2006

Free books

Danny Sullivan at Search Engine Watch has an informative post about the new option to download pre-1923 (public-domain) books from Google Book Search.

Oh sleepies!

What do you call the crusts of dried mucus that you sometimes have to rub or wash out of the corners of your eyes when you wake up? The dialect map that Bert Vaux collected for this item shows the variants sleep, sleepers, sleepies, sleepy bugs, sleepy dust, sleepy seed, eye crud, and several others, without suggesting much in the way of geographical regularity. It looks like Americans have a lot of idiosyncratic and mostly childish names for this substance. But none of us, as far as I know, pronounce any of these names in order to express frustration, annoyance, exasperation or pain.

In Finnish, I've recently been told, the word for sleepies is rähmä, and when something fails in a frustrating way, you can exclaim "voi rähmä!", where voi is an exclamation similar in force to English oh. I should add that, according to my Finnish correspondent, this expression "is pretty strongly associated with a local long-time celebrity who tended to use it in a TV show". And an online Finnish-English dictionary offers somewhat more generic glosses for rähmä, like "discharge" and "secretion". Not that muttering "oh secretion!" seems a whole lot more satisfying, as a way to discharge frustration, than "oh sleepies!" is.

This came up because I was quoted a couple of days ago in a Philadelphia Inquirer column by Faye Flam ("Why are sex words our worst swearwords?", 8/28/2006) , repeating something that I'd been told a long time ago by another Finn, namely that Finnish cuss words have to do with religion rather than sex. Since my knowledge of such aspects of Finnish is limited to these rather casual memories, it's lucky that what Faye actually quoted me as saying is apparently not completely false:

You can't employ Finnish sexual words to swear, he says, since it would come out something like "Oh, intercourse!"

According to my anonymous Finnish correspondent:

This is pretty much true for words about sex or intercourse, but not about sexual organs. The hands down most common Finnish swear word vittu translates as "vagina", although the way it's used corresponds very well to English fuck. If something or someone is unpleasant, he or it is vittumainen, "vagina-like". If you run your mouth at someone, trying to provoke or embarass, the verb is vittuilla.

You can also call a person a mulkku, which translates as "penis". Kyrpä is also a rather uncivilized word for penis and it can be used to refer to an unpleasant person or when cursing out loud: "voi kyrpä!" (voi = oh). You can also blurt out "voi perse" (= "oh arse"). Someone who's an asshole in English would be vittupää (vagina-head) or kusipää (urine-head) in Finnish, etc. Then you have creative stuff like "voi vitun viikset" (= "oh vagina's moustache") and so on. If someone has "a penis on his forehead" ("kyrpä otsassa"), he's very disgruntled indeed.

The possible source for this misunderstanding is that apart from vittu, which many younger people use as a comma, most of the commonly used swear words in Finnish are indeed about devil, hell or similar religious affairs. So, there is a distinct register of strong swear words that are not sexual. Apparently the word vittu was originally about animistic magic and it was used to call up the magical power of women or the female genitalia. The idea of a male using it as a swear word was apparently rather ridiculous.

Not as ridiculous as cussing about sleepies, in my opinion. Of course, the whole cussing phenomenon is faintly ridiculous, when viewed in the light of reason. Anyhow, I feel that I got off easy in my role as a self-appointed expert on Finnish cussing, compared to Bill Bryson. My anonymous Finnish correspondent explained:

When talking about Finnish language with foreign people, you very often find out that for some weird reason someone in the group knows one or two Finnish swear words. This makes a certain legendary misunderstanding about Finnish swearing rather amusing. Some devious person fooled the author Bill Bryson to think that there's only one swear word in the Finnish language: ravintolassa, which means "in a restaurant".

Bill Bryson's gullibility and carelessness is on display in his book The Mother Tongue, about which one Amazon reviewer writes:

... as many others have pointed out, every page is just error after factual error. Bryson simply does not understand how languages work, and whatever his sources are are frequently wrong. My favorite mistake is when he claims that in Finnish, there is only one swear word, ravintolassa, meaning "in the restaurant" (page 214). Now, ravintolassa DOES mean "in the restaurant," but that's ALL it means. Finnish has plenty of native swear words (saatana, perkele, vittu, jumalauta, and more), and I still cannot imagine how Bryson came to the conclusion that, not only did it have only one, but that it was the word for "in the restaurant." It's truly mind-boggling.

[Of the four Finnish cuss words cited, three are religious: saatana = "satan", perkele = "traditional Finnish thunder god" (currently also a name for the devil), jumalauta = "God help". The wikipedia article on perkele asserts that

The term also has the role of realizing and strengthening the Finnish national identity. It is a typical Finnish masculine curse word, used to appeal to Finns as a rural attitude in which trouble is faced and conquered with determination and direct action. This has also inspired to the today quite commonly used (originally Swedish) expression "Management by perkele" to describe the often somewhat stern attitude among Finnish chief executives.

The following comment was removed from the same entry as being "stringly [strongly?] POV":

'Perkele Satan' is a common expression used to expres piss offedness. However, this is just a pure anger expression. I am finnish and knew nothing about thunder gods and swedish priests and crap adopting this and turning our wonderful gods into satanistic worshipping people. So, I don't quite see how you can put so much history and stuff into a simple word that is really only the finnish equal of 'God Damnit!!'. God damn the people who turned this fine finnish expression into the material of a dictionary.

This deserves to be preserved as an example of "lexicography by perkele". ]

I suspect that the spectacular "in a restaurant" blunder reveals something about Finnish deadpan humor as well as something about Bryson's scholarship, so perhaps we should reserve judgment about that whole "penis on his forehead" thing, pending further lexicographical research. But blindly trusting that that my anonymous Finnish correspondent is not a "devious person", we can continue with the Finnish cussing lessons:

... there are no words about sexual intercourse that correspond functionally with the English word fuck. There are several widely used vulgar expressions for sexual intercourse which are at least somewhat demeaning and impolite. They correspond with such English expressions as "screw", "bone" etc. Those kinds of expressions are not something you'd use in polite situation or around older people you don't know, but depending on the relationship, you can use them playfully with your girl or boyfriend or spouse. You can't really swear or curse with them, though. If you tried, you'd pretty much end up saying something weird like "oh, screwing", unless you got creative. Well - you can call a person a "wanker" in the same way as in English, if that counts.

And "oh sleepies" makes more sense when we realize that sleepies are basically dried mucus, and another way that Finns voice frustration is with "voi räkä", meaning "oh snot".

There's a theory about how all this stuff works, not only in Finnish but around the world. In fact, as you'd expect, there are several theories. More on that another time -- for now, here are some other Language Log posts on related topics:

"The FCC and the S word" (1/25/2004)

"The S-word and the F-word" (6/12/2004)

"You taught me language, and my profit on't/ it, I know how to curse" (7/17/2005)

"Curses!" (7/20/2005)

"Goram motherfrakker!" (6/7/2006)

"The history of typographical bleeping" (6/10/2006)

"The earliest typographically-bleeped F-word" (6/15/2006)

"Avoiding the other F-word" (7/4/2006)

"C*m sancto spiritu" (8/7/2006)

[And, courtesy of amazon.com, here's the passage on p. 214 of The Mother Tongue where Bill Bryson exhibits his gullibility and/or ignorance of Finnish:

Some cultures don't swear at all. The Japanese, Malayans, and most Polynesians and American Indians do not have native swear words. The Finns, lacking the sort of words you need to describe your feelings when you stub your toe getting up to answer a wrong number at 2:00 A.M., rather oddly adopted the word ravintolassa. It means "in the restaurant".

Given how badly Bryson got taken by the Finnish restaurant gag, it'd be smart not to trust his word on Japanese, Malay, or American Indian languages either. And indeed, a bit of web searching turns up plenty of information about cussing in all of these.]

August 29, 2006

Science is... a verb??

From an article in Salon last week about Michael Shermer of the Skeptics Society:

We've got to get past this idea that science is a thing. It isn't a thing like religion is a thing or a political party is a thing. It's true that scientists have clubs. They have banners and meetings and they drink beer together. But science is just a method, a way of answering questions. It's a verb not a noun.

And faith is a verb, and God is a verb, and fashion is a verb, and happiness is a verb... and so on and so on and so on.

It has become clear to me that there's no point in railing against this trope, or telling these people to get the dictionary out. They cannot conceivably think they are talking about the correct part-of-speech classification of words. They don't need or want a dictionary. When they say "is a verb" they clearly mean something like "is something that must be engaged in, or be engaged with, as an active practice".

And that would be fine, except that for grammarians such as me it is a sad reminder of how the unworkable old definitions of terms like "noun" and "verb" still hold sway, nothing having changed in a century, and not much in a millennium.

It absolutely is not the case that you can coherently define lexical categories this way — nouns as words that name things, verbs as words for actions, adjectives as words for qualities, prepositions as words for relations between things, and so on. It simply does not work. It part of an ancient theory of grammar that is not just sick but dead on arrival, like the phlogiston theory of combustion. Only grammar never had its chemical revolution as far as the general public is concerned. Some time in the future the prevailing nonsense about grammar, on which the "is a verb" snowclone is based, has to be replaced by one that works, and the non-linguistic public has to be convinced (if there is ever to be sensible public discourse about linguistic matters) that the revised view provides a more sensible and coherent theory. This is not going to be easy.

[Many thanks to Jonathan Lundell and Tam K for the tipoff.]

By any other name

Mark Liberman reports, once again, on misapprehensions of Gregory Pullman's Geoffrey Pullum's name. This after a week in which a blogger managed to get <Geoffrey K. Pullum> and <Roger Shuy> right (angle brackets enclose spellings) -- no small trick -- but stumbled some on <Mark Liberman> (just the usual <Lieberman>) and fell flat on his face with <Arnold Zwicky> (<Andrew Zwickey>). Both Geoff and I have large collections of manglings of our names, painstakingly (or pain-stakingly) assembled over many years, but this is the first time I've been called Andrew. <Zwickey>, thousands of times, but Andrew, no.

There's some linguistic interest, as well as entertainment, in where these misnamings come from.

First names first. Almost all these errors come from replacing the relatively rare first name Arnold with a more common one of similar form: in rough order of decreasing frequency, Ronald, Donald, Harold, Albert, Leonard, Howard.

What's similar here? Well, Arnold and the other six are all two-syllable names with accent on the first syllable. More impressively, they all fit the phonological template:

where C is any consonant, VLAX is a lax vowel (a, æ, or ɛ), S is a sonorant consonant (nasal n, liquid r or l, or glide w), and L is a liquid (r or l). Arnold manages to have TWO sonorants (r and n) in the middle. Also note that d and t are alveolar oral stops, differing only in voicing. Ronald is really VERY close to Arnold, differing only in the ordering of a and r, so it's no surprise it's by far the most common error.

In this context, Andrew is really pretty far off the mark, though (like Arnold) it starts with a lax vowel, and its consonants n, d, and r are all there in Arnold, but in the grossly different order r n d. So I'm not surprised it's never come up before.

In any case, the other first-name errors above -- of perception and/or memory -- show just how much speakers are sensitive to phonological properties and relationships.

The remaining errors on my first name are spelling mistakes, and are not very common: <Arnald> and <Aronold>. <Arnald> might involve a perseveration of the first vowel letter, but the effect is probably mostly the old problem of how to spell unaccented vowels in English: <a>, <e>, <i>, <o>, and <u> would all be possible, in principle, in the second syllable of my first name. (<Arnuld> occurs fairly often, but almost always with reference to the current governor of California, and never, so far in my experience, with reference to me.) In this case, <Ronald> and <Donald> probably tip things towards <a>. As for <Aronold>, this is surely an orthographic anticipation of the <o> in the second syllable of <Arnold> -- evidence that the writer is already thinking ahead to the second syllable at the end of the first.

Most of the misnaming action is in my family name. Some of it is phonological, a result of the fact that zw is a marginal initial cluster in English; it's "hard to pronounce" for English speakers, who try to improve on it in one of three ways:

(1) replacing the z by its voiceless counterpart s, to get a fine English initial cluster, sw: Swicky; this is probably the most common fix in writing (you can google up a bibliography in which a reference to Zwicky & Sadock 1975 on ambiguity tests gives <Swicky> as the first author), and it's pretty common in speech.

(2) breaking up the difficult zw cluster by inserting a schwa, which will appear in writing as <a>, <o>, or <e> (these choices of vowel probably facilitated by the fact that <Zawicky>, <Zowicky>, and <Zewicky>, and versions of these with initial <S>, and versions of these with final <ey>, are attested Slavic family names); this is probably the most common fix in speech -- even I regularly insert the schwa when I want to make my name clear to people, though that's inclined to lead them to this type of misspelling -- and it's not very frequent in writing.

(3) omitting one or the other of the two consonants in zw, to get Wicky or (occasionally) Zicky. More common in speech, where it probably results from mis-hearing, than in writing.

The most creative approach to my family name was taken by a data processing staffer at the Mitre Corporation, where I worked during the Cretaceous Era. Faced with that zw cluster, she apparently decided not to abandon the w, but to hold it off until there was a place for it. This would have produced something like Zickwi (yes, a fourth possible fix), but the staffer seemed to feel that this didn't do credit to what she saw as a Slavic name, so I became Mr. Zickwich. (I was so charmed by this that I didn't correct her. Anyway, I didn't want to get on her bad side, since she was the person who cared for all the punch cards for a gigantesque program I was working on.)

On to purely orthographic errors in my family name, most of which have to do with the ways of spelling final unaccented i. It's <y> (as in <sticky>) in my actual family name, but the system linking sounds with spellings in English orthography offers several competitors: in descending order of frequency, <ey> (as in <Mickey Mouse>), <i> (as in <Micki and Maude>, a 1984 movie), <ie> (as in <Mickie James>, the woman wrestler). There are also <ee>, as in <Mickee Faust> ("The Mickee Faust Club is Tallahassee Florida's tongue-in-cheek answer to a certain unctuous rodent living in Orlando"), and <ye>, as in <Mickye Adams> (an actress), but I have no attestations of <Zwickee> or <Zwickye>. <Arnold Zwickey> is on the web, in a Lavender Languages conference announcement from Bill Leap. So is <Arnold Zwicki>, in a comment on the eggcorn database. (And to be fair, the family tree includes some who have re-spelled the name to a more Swiss-German-looking <Zwicki>.)

Every so often I get <Zwiky>, without the <c> that signals a preceding lax vowel, so that it looks like it ought to pronounced like <Mikey> (most likely) or <tiki> (if it's a "foreign" word). But we now have <wiki>, with a lax first vowel, so even this version makes some sense.

At least one error probably results from people having trouble deciphering my handwriting: <Arnold Zuckey>, with a <u> for my written <wi> (plus our old friend, final <ey>). Maybe <Arnold Zwidry> belongs here too. <Professor Zwinky> doesn't, because the editor who addressed me this way had just typed my name correctly in the line above; she was, unfortunately, unable to reconstruct what had happened -- but it was certainly an inadvertent performance error.

You can see what happened in another inadvertent performance error: <Arnold Zwizky>, with the <z> persevering from the first syllable. And in the anticipatory example <Zrnold Zwicky>. And in the modestly frequent, though at first glance very surprising, <Zqicky> (the NAACP is determined to address me this way, and they're not alone); look at your keyboard. Even better, two in one blow: <Arjold M. Zqicky> (from Greenpeace, obviously having someone type address lists rather than using pre-printed address labels).

The errors can be compounded. I have, alas, no idea what led from <A. M. Zwicky> to the remarkable <A. H. Tricky>, but I can reconstruct the path from <Zwicky> to <Soicky>: <Zwicky> to <Swicky> (easy step), <Swicky> to <Sqicky> (the typing error just above), and then, wonderfully, <Sqicky> to <Soicky>, when some human being notices the impossible <Sqi> and assumes it's an error based on the visual similiarity of letters, so fixes the <q> to the visually similar (and orthographically possible) <o>; <p>, giving <Spicky>, would also have been possible, and I'm hoping to live long enough to see a <Spicky>.

Next, global foul-ups in mailing lists, where pieces of entries get transposed. This has produced mail (with the right street address) for Arnold Zweig (probably there was a Zweig just before me on this list) and for Arnold M. Osland (there is an Arnold Osland who's a Republican district chairman in North Dakota, but what mailing list would we have been on together? there are no Oslands in the local telephone directory, by the way).

Finally, my favorite category, the Vulcan Identity Meld, in which conjoined names are combined into a single name: Elizabeth Arnold (a delightful person in whom my daughter Elizabeth's best qualities are joined with mine), Jacques Trazwicky (making a true marital unit of my partner Jacques Transue and me), and, incredibly, Jacque Arnold Transuzwicky (an elaborate interleaved Vulcan Identity Meld, plus the annoyingly common misspelling of <Jacques> as <Jacque>, which has led many to assume Jacques was a woman whose name was pronounced like <Jackie>.)

soicky at-sing clsi peroid standford peroid edd

Language Log type size

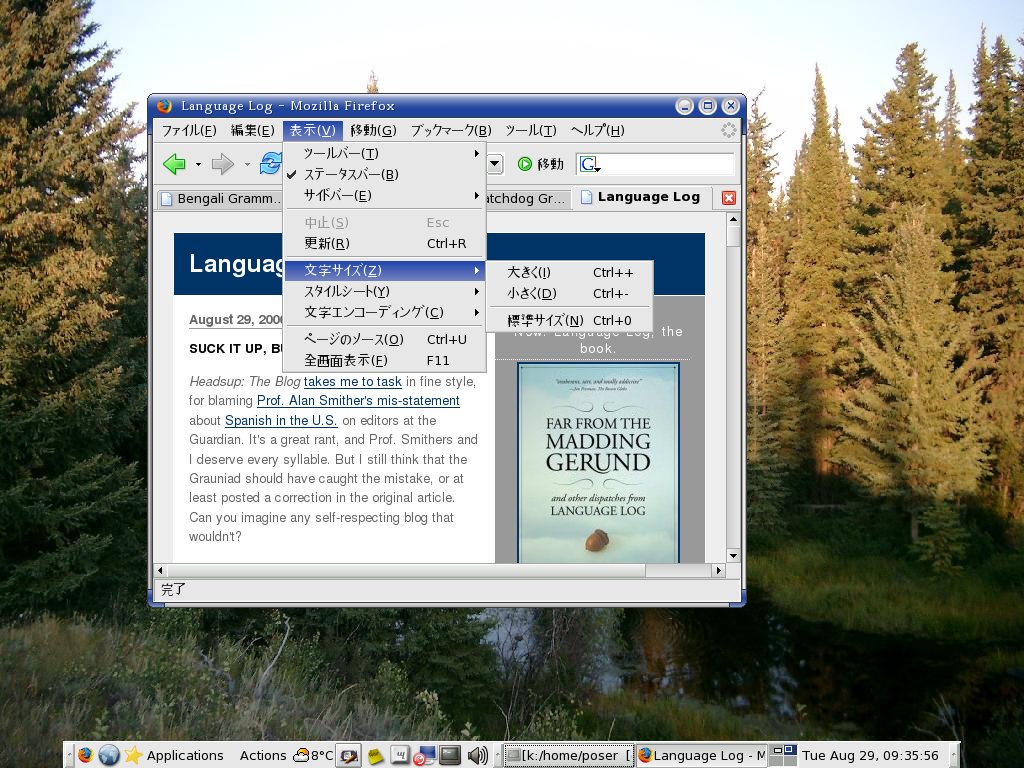

Some readers tell us that they have difficulty reading Language Log because the type is too small and faint. For me, the type in Language Log is fine, but I find the type on some other sites difficult to read. Type weight is a bit harder to control — perhaps we should change the stylesheet to use a heavier typeface — but fortunately, it is easy to enlarge the type in your browser, or to make it smaller if you prefer. Most if not all browsers have a type size control either right on the front panel or on an easily accessible menu. I'm currently using Mozilla Firefox most of the time. In Firefox, the control is on the View menu (the third from the left). The sixth item down, the first in the third group, is the character size submenu. Here's a screenshot:

Mark Liberman tells me that in Internet Explorer as well the View menu has a Text Size submenu.

All of the browsers that I have tried also respond to Control-+ to increase type size and Control-- to decrease it. Eric Bakovic reports from Macintosh-land that this is true of Safari as well except that one uses Command-+ and Command-- instead.

Suck it up, buttercup

Headsup: The Blog takes me to task in fine style, for blaming Prof. Alan Smither's mis-statement about Spanish in the U.S. on editors at the Guardian. It's a great rant, and Prof. Smithers and I deserve every syllable. But I still think that the Grauniad should have caught the mistake, or at least posted a correction in the original article. Can you imagine any self-respecting blog that wouldn't?

[Update -- Nicholas Lawrence writes:

For the record, the on-line version of [Smithers'] original article now says "pockets of".

]

A Geoffrey by any other name

In the Chicago Tribune a few days ago, Julia Keller took a stylistic look at Vice President Cheney ("Cheney's usage of 'if you will' is 'like' hedging", 8/24/2006), and cited Gregory "Grisha" Pullum's classic Language Log post "It's like, so unfair" (11/22/2003).

For the rest of us here at Language Log Plaza -- Arnold Zwickley, Boris Zimmer, Sally Thompson , and all -- references in the popular press are rare enough that we need to echo George M. Cohan's plea “I don’t care what you say about me, as long as you say something about me, and as long as you spell my name right.” (I expect that "Cohen" was a special problem for him.) But Jeff Pullman, whose names seem to be everywhere these days, has transcended mere nomenclature.

Bogosity

In response to Arnold Zwicky's post on Snickers morphology, several readers have written to reference the much-loved Jargon File entry for bogosity:

-

1. [orig. CMU, now very common] The degree to which something is bogus. Bogosity is measured with a bogometer; in a seminar, when a speaker says something bogus, a listener might raise his hand and say “My bogometer just triggered”. More extremely, “You just pinned my bogometer” means you just said or did something so outrageously bogus that it is off the scale, pinning the bogometer needle at the highest possible reading (one might also say “You just redlined my bogometer”). The agreed-upon unit of bogosity is the microLenat.

-

2. The potential field generated by a bogon flux; see quantum bogodynamics. See also bogon flux, bogon filter, bogus.

You should also consult the entries for bogotify, where the coinage autobogotiphobia is described as "a self-conscious joke in jargon about jargon", a phrase with some current relevance; and coefficient of X, where the subtle but important difference between "foo index" and "coefficient of foo" is exemplified as follows:

Foo index and coefficient of foo both tend to imply that foo is, if not strictly measurable, at least something that can be larger or smaller. Thus, you might refer to a paper or person as having a high bogosity index, whereas you would be less likely to speak of a high bogosity factor. Foo index suggests that foo is a condensation of many quantities, as in the mundane cost-of-living index; coefficient of foo suggests that foo is a fundamental quantity, as in a coefficient of friction. The choice between these terms is often one of personal preference; e.g., some people might feel that bogosity is a fundamental attribute and thus say coefficient of bogosity, whereas others might feel it is a combination of factors and thus say bogosity index.

I was always especially fond of the term microLenat:

-

The unit of bogosity. Abbreviated µL or mL in ASCII Consensus is that this is the largest unit practical for everyday use. The microLenat, originally invented by David Jefferson, was promulgated as an attack against noted computer scientist Doug Lenat by a tenured graduate student at CMU. Doug had failed the student on an important exam because the student gave only “AI is bogus” as his answer to the questions. The slur is generally considered unmerited, but it has become a running gag nevertheless. Some of Doug's friends argue that of course a microLenat is bogus, since it is only one millionth of a Lenat. Others have suggested that the unit should be redesignated after the grad student, as the microReid.

BOGOSITY n. The degree to which something is BOGUS (q.v.). At CMU, bogosity is measured with a bogometer; typical use: in a seminar, when a speaker says something bogus, a listener might raise his hand and say, "My bogometer just triggered." The agreed-upon unit of bogosity is the microLenat (uL).

I always thought that bogosity was formed by self-consciously false analogy to porous/porosity and other pairs of that type. Note that this element introduces the resonance of an adjectival form nougatous to the Snickers coinage. I also suspect that bogosity in turn influenced the coinage of travelocity, where the echo of velocity also comes into the picture, and this may also be one of the resonances of nougatocity.

[Update -- Ben Zimmer points out that:

Another form likely influenced by bogosity is bozosity/bozocity, as I noted in a comment on Double-Tongued Word Wrester.

By the way, Geoff Nunberg referred to "the administration's apparently bottomless bozosity" in a June 11 LA Times column.

]

[Update #2 -- Blake Stacey writes:

The closest I have seen to the "hackish" term "bogometer" entering a broader field of discourse is in the New York Times coverage of the

Bogdanov Affair, in which two television personalities managed to earn Ph.D.s by publishing artful nonsense. Quoting reporter George Johnson,This is where experts say that sincere or otherwise, the Bogdanovs' papers fall flat. Reading through an Internet debate between them and the physicist John Baez of the University of California at Riverside is like watching someone trying to nail Jell-O to a wall. It is as though the Bogdanovs, like twins one reads about in psychology experiments, have developed their own private language, one that impinges on the vocabulary of science only at the edges.

If so, then their argot was apparently good enough to get past the gatekeepers at the University of Bourgogne, where the brothers recently got their Ph.D.'s with dissertations their colleagues find as baffling as their papers. (Some scientists are amused that long before anyone outside France had heard of the Bogdanovs, the term "bogometer" had been used to describe an imaginary device that blinks frantically when confronted with a bogus claim.)The Wikipedia article on this affair has experienced some serious slings and arrows, mostly because people involved came along in person to slant its coverage they way they want to be seen (quite a "the map is not the territory" moment). However, now that the heyday is past, it's much more informative.

Johnson's parenthetical connection between Bogdanov and bogometer seems dangerously close to making fun of someone's name, which is generally considered to be an inappropriate form of argument. He's half-rescued in this case by the anonymous attribution to "some scientists".. ]

[Update -- Topher Cooper writes:

Found the posting on “bogosity” and the “microLenat” from the Jargon File interesting, largely because it doesn’t agree with my memory in a number of particulars. I was a part-time undergraduate working full-time for the AI department at C-MU during the period when the term was commonly in use.

The definitions are fully in accord with how I remember it being used – it’s the origin that seems a bit flakey. Mind you, my memory could be at fault.

From the proposed alternative unit – the microReid – I’m guessing that the grad student in question was Brian Reid. The problem with the whole story is that Doug Lenat was at the time a grad student at Stanford while Brian was a grad student at C-MU. Brian had previously been at the University of Maryland and worked in industry (yes, I checked his Wikipedia entry, but it is basically what I remembered). It doesn’t seem likely that he was ever a student of Lenat’s.

There were a bunch of people in the AI group at C-MU who had previously been at Stanford. My impression was that they introduced the use of the term to C-MU.

The explanation that I received for naming the unit of bogosity after him was that he was someone who would generate more ideas in five minutes than most people do in a week – sort of a comp sci Robin Williams. Of course, nearly all of those ideas were completely bogus. Every once in a while, though, one of those ideas was a true gem. That still left him with more good ideas a week than most people. Someone once suggested that the microLenat was an unusual unit of measurement because there were only 999,999 microLenats per Lenat – the one remainder measured something quite distinct from bogosity. I had met Lenat at conferences and attended some of his chaotic presentations so this explanation made a lot of sense to me.

Although I don’t remember any particular connection between Brian Reid and use of the term microLenat I could easily see where Lenat’s style -- which contrasted rather sharply with Brian’s – may have been grating to Brian. It is possible that he used the term with a bit more bite to it to someone outside of C-MU, giving rise to the sour grapes story.

]

August 28, 2006

Playing with your morphology

Advertisers like to play with language. People notice, and maybe, they'll then remember.

So we get the latest Snickers ad campaign, in which striking invented words appear (on billboards, sides of buses, etc.) in the characteristic Snickers font and colors, on a chocolate brown background that looks like a Snickers wrapper. The words:

hungerectomy

peanutopolis

nougatocity

substantialicious [see correction below]

satisfectellent

We here at LLP are not the first to comment on the phenomenon; google on "Snickers" plus one of the words (especially the last), and you'll find lots of discussion, ranging from admiration to annoyance to mockery. Most of the commentators see the words as combinations of two contributing existing words (combinations that Lewis Carroll called "portmanteau words"), but that's not quite right, and the Playful Morphology office at LLP (which produced "Plain morphology and expressive morphology" [Berkeley Linguistics Society 13.330-40] back in 1987) is here to tell you about it.

Start with hungerectomy. This combines a base hunger with the medical suffix -ectomy, referring to a surgical removal, as in appendectomy and tonsillectomy. The (vivid, perhaps over-vivid) imagery is of a candy bar that physically removes hunger from your body. Not really a portmanteau, but instead an extension of the noun bases eligible for combining with -ectomy, from medical ones to anything goes. There are plenty of other nonce formations on non-medical bases: truthectomy, funectomy, zitectomy, for instance. [Ben Jackson notes that the -rectom- piece of this word is homophonous with rectum -- not a good thing.]

Peanutopolis is similar.

The base is peanut, the

suffix -opolis, used for city

names (Greek polis 'city'

with a combining vowel -o-

for bases ending in a consonant, as in English metropolis and necropolis). So it conveys

Peanut City, which is pretty good. Once again, the base isn't of

the Greco-Latin sort that you'd expect, so it's noticeable. In

this case, there's a fairly long tradition of such combinations in

place names (based on nouns), often jocular: porkopolis,

cornopolis, cottonopolis, steelopolis, and more.

Nougatocity is several steps

more complicated. My guess is that the ad agency's impulse was to

combine nougat with the

Latinate suffix -ity, which

forms abstract nouns from adjectives, to get something conveying 'the

state or essence of being nougat'. This would be noticeable in

two ways: the base is from the wrong stratum of the vocabulary, and

it's of the wrong category (noun rather than adjective). Ok,

that's playful morphology for you.

But there's a phonological problem. The suffix -ity is one of those that requires accent on the syllable immediately preceding it, so the accent on the base will shift to accommodate this requirement (compare ACtive with acTIVity). But that obscures the identity of the base word, not a desirable outcome for the Snickers people, who would want nougat to stand out clearly: NOUgat, but nouGATity. Ugh. There's a fix for this: use another suffix in between the base and -ity, so that nougat can keep its accent, and the extra suffix will get the accent required by -ity. I'd expect -ic to be the intervening affix, as in multiple - multiplicity. That would give nougaticity.

The ad agency didn't go for nougaticity, maybe because the high front vowel in -icity sounds too small or precious (the symbolic values of vowels have long been known). Instead they went for a nice big back vowel in -ocity, despite the fact that the reasonably common words in -ocity (precocity, velocity, ferocity, reciprocity, atrocity) aren't likely to be ones they wanted to evoke.

[Update, 8/29: Suzanne Kemmer writes to supply a much simpler account. Since 1988 she's taught classes on English words, in which she collects student reports on neologisms. She says, "-ocity is one of the current favorite suffixes deriving nouns from adjectives (and now, from nouns too). It seems to have the flavor of a humorously faux-Latinate derivation. It is very widespread among college students." She suggests a connection to bogosity, a word that Mark Liberman has now posted on, and concludes, "The coiner on the ad campaign was probably young and knew the popular -ocity suffix; or found a test group of youths who suggested the word." Sounds good to me.]

Now, substantialicious. This looks like a portmanteau of substantial and delicious, and maybe that was what the writers were after. But there's also an evolving jocular suffix -alicious (also spelled -ilicious and occasionally -elicious), conveying a high degree of some desired property, as in the (fairly widely attested) crunchalicious, crispalicious, and yummalicious (and probably others; these are just the ones I've noticed), and that might be the analysis of substantialicious. [Turns out that the ads actually have the spelling substantialiscious, maybe to evoke luscious. Google sources have both spellings, and this is one I hadn't seen on the hoof, so I was misled. The ad strategy seems to have been to throw in as much as possible and hope that some of it sticks.]

[Further addenda, 8/29: Jason Parker-Burlingham and Jim Wilson write, separately, to say that the -alicious words remind them of the coining sacrilicious (a portmanteau of sacrilegious and delicious) on "The Simpsons" in 1994 (for the story, see the Wikipedia site on Simpsons neologisms). Wilson suggests, in fact, that the -alicious words are cloned from sacrilicious. I'm a bit dubious about this, since my impression is that crunchalicious, at least, pre-dates this Simpsons episode. But I don't have any actual evidence, so I'm keeping an open mind. As for echos and reminders, Jack Hamilton tells me the word reminds him of Mary Poppins: supercalifragilistic!]

(That 1987 BLS paper by Geoff Pullum and me looked at some evolving jocular suffixes that had already been discussed in the morphological literature: -orama/-rama/-ama and -eteria/-teria/-eria for shop names. A variety of suffixes created from pieces of existing words are now inventoried in Michael Quinion's Ologies and isms: Word beginnings and endings (Oxford Univ. Press, 2002).)

Substantialicious is merely not very compelling. But satisfectellent, apparently some sort of odd portmanteau of satisfaction (or satisfying) and excellent, is a real stinker. For a lot of people, this one evokes, not these words, but fecal and repellent, not a good thing in a word that appears on a brown background. [Addendum: you might hear an echo of infect in there as well, also an unfortunate effect. Further addendum, 8/29: J.D. Stephens suggests that you might hear the unpleasant feculent in there too, if you know the word.]

Just a reminder: these words are not to be found in dictionaries. That's the whole point; they should be ostentatiously novel, but still interpretable. They should be crunchalicious inventions.

[Thanks to Doug Kenter for encouraging me to post on the Snickers ads. They were, as he put it, carefully, driving him nuts.]

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

A bad week for the lord of the underworld

You'd think that Pluto had just lost a contract with Viacom. Everyone has been worrying about whether Pluto is a planet or not, thereby proving that planet or no planet, Pluto is still a star:

The Washington Post turned it around the other way, with "5 Things that Need a Downgrade like Pluto": Godfather III, Gluttony, Tour de France, Segways, and Tom Cruise.

Simon Beck in the Globe and Mail took a more conventional line with "A star and a dwarf crash in war of worlds":

This week was marked by two of the most famous pink slips in recent history, as Pluto lost its job in the solar system and Tom Cruise lost his corner office in the star system.

Bert Caldwell in Forbes used the same equation in the lead for an article about magazine rankings of this and that:

Astronomers disowning planets. Hollywood casting out stars. Washington ranked 41st among the 50 states for quality of life. Just what in the name of this cosmos is going on here?

And Matt Shurrie in the Woodstock Sentinel-Review really let it all hang out:

Yes, the elite eight have thrown their one-time sibling to the curb - simply because it doesn’t measure up.

How typical. How rude.

Sure, the astronomical union defended the move by expressing its deepest affection for Pluto - Jocelyn Bell Burnell, a specialist in neutron stars from Northern Ireland, even joked that some sort of new umbrella called ‘planet’ had been created, drawing laughter by waving a stuffed Pluto of Walt Disney fame beneath a real umbrella.

However, anyone could see right through those hollow feelings.

If our ninth planet - sorry, former planet - can be removed without much of a second thought, it makes one wonder what’s next.

If size has become such an astronomical issue, what about those of us back here on planet Earth that somehow don’t measure up?

Now that Pluto has been classified as a “dwarf planet” could those among us characterized by their “dwarf” size be next on the chopping block?

A quick look at the entertainment, music and professional sports industries reveals a number of potential candidates facing the axe. Dolly Parton, the five-foot country singer; Danny Devito, the five-foot actor/director and Theo Fleury, five-foot-six hockey player are only the tip of the iceberg.

There are plenty more including Michael J. Fox, Gary Coleman, Tom Cruise, Verne Troyer and rapper Ja Rule. Not even former quarterback Doug Flutie and former Toronto Maple Leafs captain Doug Gilmour could consider themselves safe.

What happened to a time and place where those smaller in stature were embraced - even celebrated - for who they are and not what society expects them to be? Has the interplanetary society really turned its back on that once proud tradition?

No, Matt, not as long as the gods still rule from Mt. Olympus.

Here's a small selection from the rest of the "Pluto as star gossip" stuff floating around in the media:

Tom Cruise, Pluto and Hollywood’s entrenched system for getting TV comedies on the air all took a beating this past week.

Tomorrow astronomers will vote whether Pluto retains its planet status. If Pluto loses, it will run as an independent.

We lost a planet from our solar system this week and it couldn’t get Jon Benet Ramsey off the front page. Talk about lack of respect for a celestial body!

Maybe the new rush of Pluto research will reveal a shocking truth: Cruise and Suozzi are actually visiting from the ninth planet - or the first ex-planet or whatever those indecisive telescope jockeys are calling Pluto now.

And even in these dog days of August, when Frank Quattrone shares the front page with Tom Cruise, JonBenet and the planet Pluto, there are serious opportunities for investors not at the beach.

'I don't care if Pluto's not a planet anymore. Pluto never did anything for me.'

While CNN's Breaking News alerts occasionally drift into the mundane — apparently Mel Gibson’s no contest drunken driving plea was urgent enough to warrant one — they are always reserved for headlines that will get people talking, like the foiled terrorist plot in Britain or the demotion of Pluto.

Now that Pluto's back in official planetary orbit, does Goofy need to hire a PR rep?

I have to think Thursday was a pretty sad day for stargazers -- and no, I'm not talking about Paramount Pictures punting Tom Clueless, er, Cruise.

Pluto was too small to be in the solar system. It will now be mounted on a ring and given to Mrs. Kobe Bryant.

Even some of the quotes elicited or chosed from people in the science biz have got a show-biz flavor:

"Pluto is a chunk of ice which controls nothing," says Michael Shara, curator of astrophysics at the Rose Center for Earth and Space at the Museum of Natural History. "Its orbit is a slave to Neptune's orbit."

All this suggests that the planets are still effectively personified, in a fuzzy sort of way. Would there be so much fuss, even in the silly season, over a decision that (say) tyrosine isn't really an amino acid after all? This is one of the many things that are left out of the kinds of "meaning" represented in traditional ontological taxonomies.

August 27, 2006

Generational style as "language"

Since we haven't had a cartoon in a couple of days:

Another Plutonian Casualty?

It's an irresistible story, right down to the quaint names of the dramatis personae. On March 14, 1930, Falconer Madan, the librarian of the Bodleian Library in Oxford, reads his 11-year-old granddaughter Venetia Burney the press story about the discovery of a new planet by the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff Arizona. She has been studying Greek and Roman mythology and tells her grandfather that the planet should be named Pluto, after the Roman god of the underworld. He relays the suggestion to the Oxford astronomer Herbert H. Turner, who in turn cables it to the Lowell Observatory. When the name is announced on May 1 by Vesto Slipher, the Observatory's director, Venetia is given due credit for her suggestion. After the story is popularized in a 1964 article in Sky and Telescope, "the girl who named Pluto" becomes a favorite topic in popular books about astronomy, and even in her 80's, Venetia is still the subject of news features and interviews.

As long as people are raining on 75-year-old planetary parades, maybe this one is worth some cold-eyed reconsideration as well.

The story has developed some elaborations over the years --some accounts, for example, have Venetia winning a contest to name the new planet. But there's no reason to doubt most of the details as they were originally given. There's no question that Turner forwarded Venetia's suggestion to Slipher, who acknowledged her as the first person to suggest the name in a May 1 observation circular (the formal announcement came later). (See William Graves Hoyt's article "W. H. Pickering's Planetary Predictions and the Discovery of Pluto," Isis 67,4, December, 1976.)

But it's hard to credit that Venetia was actually the first to bring up Pluto as a potential name. In a BBC interview published on January 13, 2006, Venetia Burney Phair herself reported that when her grandfather first went looking for Turner, he turned out to be at a meeting of the Royal Astromical Society in London, where people were naturally speculating on the name of the new planet.

"None of them came up with Pluto. That was another stroke of luck," says Mrs Phair. When Mr Madan eventually caught up with Herbert Hall Turner, the astronomer agreed Pluto was an excellent choice.

No doubt that's what her grandfather or Turner told the 11-year-old -- anyway, it's what I would have told my daughter in similar circumstances. But it's virtually certain that "Pluto" was already being bruited about by the members of the RAS and by astronomers elsewhere, including those at the Lowell Observatory. Inasmuch as the planets were conventionally named after Roman gods, it's hard to think of a choice more obvious than the name of "the god of the regions of darkness where Planet X holds sway," as Roger Lowell Putnam, a trustee of the Lowell Observatory, said on May 25, 1930 in announcing the choice of the new name that would be submitted to the American Astronomical Society and the RAS ("Pluto Picked as the Name for New Planet X Because He Was God of Dark Distant Regions," as the New York Times zeugmatically titled its 5/26/1930 article on the announcement). And the name was all the more appropriate, as Putnam noted, because Pluto was the brother of Neptune and Jupiter (as well as being the son of Saturn, he might have added). But Putnam made no mention of Venetia in the public announcement. And given that astronomers were rifling through the lists of Roman gods from the moment of the new planet's discovery -- and indeed, from well before that date, in anticipation -- it's not credible that Slipher would have opened the telegram containing Venetia's suggestion and said, "Pluto! Now why didn't we think of that one?"

In fact the name Pluto had occurred to other people, and some were already using it. A story in the New York Times on March 25, 1930, two months before Putnam's announcement, reported that the Italian astronomers at the Breara [sic -- actually Brera] Observatory who had photographically corroborated the discovery of Planet X had provisionally given it the name Pluto "because that ancient divinity was related to others for whom planets are named," being "the son of Saturn and the brother of Jupiter and Neptune." (The same story was carried in a March 25 AP dispatch.) Slipher must have known about this well before the date of the stories, since the Lowell Observatory must have been in touch with Emilio Bianchi and the other astronomers who made the observations. And by March 28, the suggestion of Pluto as a name was already being criticized by the astronomer Hans Hoerbiger of Vienna (who argued that since the planet consisted cheifly of frozen water, a name relating to Neptune should have been used.) (NYT 3/29/1930).

But if the name Pluto was adopted from the Italians or was simply in the air, why would Slipher have credited Venetia for playing a decisive role in his May 1 circular? Perhaps he simply felt that the story added a charming note of human interest -- and after all, Venetia really had suggested the name, and crediting her with first discovery would have been seen as a gracious gesture to Turner (a former Astronomer Royal) and the English. Slipher may also have wanted to reserve credit for the name to the Anglo-American sphere, rather than acknowledging that the Italians had come up with it first.

Or perhaps there's an additional explanation. As Hoyt points out in his 1976 article, the name Pluto was also being used by the astronomer William Henry Pickering. A fecund predictor of hypothetical planets, Pickering had conjectured a trans-Neptunian "Planet O" between 1919 and 1928 on the basis of perturbations in the orbit of Neptune, a theoretical rival to Percival Lowell's Planet X, which the Lowell Observatory had set itself to find. Given the rivalry that had developed between Pickering and the Lowell Observatory staff, it's no wonder that Harlow Shapley, the director of the Harvard Observatory, would warn Putnam two days after the discovery was announced that "we shall soon be hearing from W. H. Pickering."And indeed, in an article published in 1930 in Popular Astronomy shortly after the discovery, Pickering identified the body found by the Lowell Observatory as his Planet O, and claimed priority of publication for the name Pluto, a name he later claimed to have been privately using for some time. When the observatory staff insisted that the body was identical with Lowell's Planet X, a dust-up ensued; in Janurary 1931, Pickering attacked Percival Lowell's work and the "surprising and reckless claims. . . put forth by his active adherents and administrators, backed by very extensive newspaper propaganda." And later, having decided that the object found by the observatory was not one of his hypothetical planets, he objected to the choice of "Pluto" as a usurpation: "Pluto should be named Loki, the god of thieves," he said. (See Hoyt, pp. 563-564.)

There is no way of knowing whether Slipher was aware of Pickering's use of "Pluto" prior to the appearance of Pickering's Popular Astronomy article. But he certainly knew of Pickering's claim before he gave pride of place to Venetia, and that may have given him another motive for crediting her with the suggestion, foreclosing speculation that the name was borrowed from Pickering. Whatever his motives, it isn't plausible that Venetia really was the first person to suggest the name of Pluto. Which is not to deny that she was a very clever young girl.

Spanish in the states

A few days ago, we looked into an article in the Guardian, which stated that "Spanish is fast rising in importance and there are now more Spanish speakers in the United States than English." I speculated that "the Guardian's entire editorial staff is on vacation, and has delegated its duties to the night office-cleaning crew, who are having a little competition among themselves to see who can slip the most extravagant falsehoods into print." But it turned out that it was simply a slip of the pen on the part of the article's author, Prof. Alan Smithers, who explained that "[t]he thought that was in my mind when I wrote that part of the sentence was `there are now more Spanish speakers in some of the United States than English'.

I was still skeptical about this modified statement. I wrote Prof. Smithers for clarification, and he was kind enough to reply.

Many thanks for keeping me posted.

The picture I had in mind was Figure 5 of the US Census 2000 Brief which shows large parts of the States bordering Mexico with 60 per cent or more, or 35.0 to 59.9 per cent, of people, five years and over, who spoke a language other than English at home. Table 4 of the same document lists the top ten areas for Spanish speakers all of which are above 50 per cent reaching as high as 91.9 per cent.

The figures are taken from the 2000 Census and are likely to have been under-estimates since they derive from a question about language spoken in the home rather than mother tongue, and the form could only have been sent to known households with reliance on an honest response. There has also been rapid growth in Hispanic migration since 2000, both legal and illegal.

I, therefore, felt justified in going for a dramatic statement. But since it has attracted attention out of all proportion to its importance in the article (which was about why we in England should not be too bothered by the decline in the learning of French and German in our schools given the increasing interest in Spanish and other languages), it should perhaps have been more qualified - though whether a more academic sentence would have survived the subbing is another matter.

Prof. Smithers is referring to census data like this:

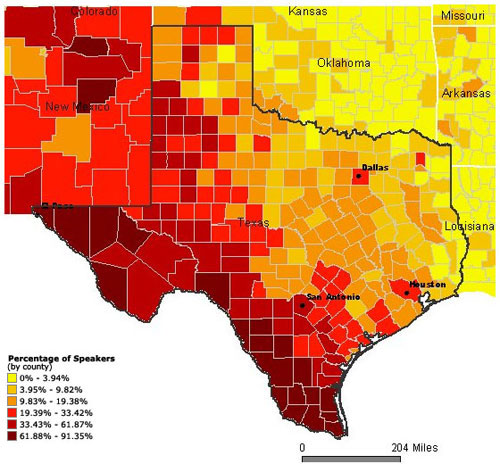

But there's a danger in generalizing too quickly from such maps, as Ben Zimmer pointed out a few months ago. Here's the same data -- proportions of Spanish speakers by county -- graphed for the state of Texas by the excellent MLA language mapping web site:

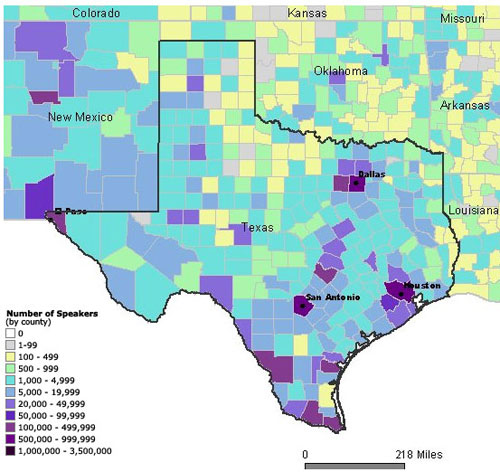

This certainly makes it look as if at least as many Texans speak Spanish as English. However, many of the counties with the highest percentages of Spanish speakers are thinly populated. If you look instead at a map by number of speakers, a different sort of picture emerges:

This helps explain why the overall population of Texas was found by the 2000 census to be only 25.5% "Hispanic". And as I understand it, this is an ethnic rather than linguistic statistic, and so the proportion of Spanish native speakers would be somewhat lower. Texas has the third-highest state-level "Hispanic" proportion, essentially tied with California at 25.8%, and behind New Mexico at 38.2%. In fourth place is Arizona with 18.8%. (According to estimates of current proportions of Spanish speakers on the MLA site, New Mexico is at 28.76%, Texas is at 27.00% and California is at 25.8%. Note also that the majority of these "Spanish speakers" also speak English "very well" or "well" -- e.g. in California, 5,593,955 out of 8,105,445.)

Prof. Smithers suggests two reasons why today's real proportions might be higher than this: census undercounting and continued immigration. Both are valid points, but I think they're unlikely to rescue his statement.

As for census undercounting, this was investigated carefully by Eugene Erickon, "An Evaluation of the 2000 Census". He estimates that Hispanics were undercounted by about 2.85%, non-Hispanic Blacks by 2.17%, and non-Hispanic Whites by 0.67%. Given these estimates and the state-level percentages given above, it's clear that not even New Mexico is going to get close to 50% Hispanic.

And as for on-going changes, the census bureau estimates that between 1990 and 2000,

The Hispanic population increased by 57.9 percent, from 22.4 million in 1990 to 35.3 million in 2000, compared with an increase of 13.2 percent for the total U.S. population [which was 281.4 in 2000].

If we project the same rates of growth forward for New Mexico and Texas, we'd predict that New Mexico would become 46.3% "Hispanic" by 2010, and Texas would become 32.3% "Hispanic". These proportions would be increased slightly by allowing for undercounting, but not as much as they would be decreased by removing the members of the "Hispanic" category whose native language is not Spanish -- according to the accounts that I've read, that would be many of the second generation and nearly all of the third. [See the 1987 movie Born in East L.A. for the (hilarious but fictional) story of Cheech Marin as a Chicano, born in the U.S. and speaking no Spanish, who is mistakenly deported to Mexico by the U.S. immigration authorities. And way back in 1969, one of my army buddies was a Hispanic guy from San Antonio whose Spanish was not very good, though his ethnic identity was strong.]

So I think it would still have been factually incorrect if Prof. Smithers had written that "there are now more Spanish speakers in some of the United States than English". It would be closer to correct to say that "several of the United States are more than 25% Spanish speaking". Whatever the exact proportions, it's certainly true that many U.S. residents speak Spanish -- which I guess was Prof. Smithers' main point.

[Update (August 28, 2006): I guess some of the Guardian's editorial staff have returned from vacation early, and so there is now a correction here, three days later and (of course) not linked from the original article, which remains in place, unchanged, to enlighten future readers... ]

Scottish dialect genetics

For some reason, the worldwide excitement over English cow dialects hasn't connected with the more localized excitement over Scottish crossbill dialects, which was also recently featured on the BBC News web site ("'Accent' confirms unique species", 8/15/2006):

Debate has raged for years among experts about whether the Scottish crossbill was unique, or a sub-species of the common crossbill.

[...]

DNA tests had shown the Scottish crossbill, common crossbill and parrot crossbill - which visits from Europe - to be genetically similar.

The results of long-running research has now found, according to the RSPB, that the Scottish variety is a distinct species of its own.

The society said it had a "Scottish accent", or call, which it uses to attract a mate from among other Scottish crossbills.

The logic here is puzzling. Cows, the BBC told us, learn their regionally distinctive moos from the farmers that tend them. (Now in fact, there's no evidence for -- or against -- regional variation in cow vocalizations. The whole thing was an empirically vacuous PR stunt. But we're talking about logic here, not evidence.) Part of the argument for the plausibility of the cow story was the well-known fact (it really is a fact) that many species of birds learn aspects of their songs, and sometimes thereby develop local song "dialects". But in this other story, separated by only a few days, the BBC tells us that Scottish crossbills, though "genetically similar" to their European cousins, are now to be treated as a separate species, because they have a "dialect":

RSPB Scotland's senior researcher Dr Ron Summers, who led the study, said: "The question of whether the Scottish crossbill is a distinct species, and therefore endemic to the UK, has vexed the ornithological world for many years and split the bird watching community.

"This research proves that the UK is lucky enough to have a unique bird species that occurs here and nowhere else - and this is our only one."

Well, maybe the crossbills are not among the bird species that exhibit vocal learning, but instead develop songs that are genetically programmed in every detail. That would rescue the logic of the story, but its author shows no sign of having considered the question one way or another, which is a little odd, since the word dialect suggests social construction rather than genetic determination. (In fact, crossbills -- a kind of finch -- do learn their songs. See below for some details.)

So I spent a few minutes finding and reading the press release at the site of RSPB Scotland. (That's the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.) This revealed where the BBC's take on the story came from -- as in the case of the regional cows, they were basically just repackaging the PR agent's press release (with a good deal of straight copying).

Quaintly, the RSPB has a picture caption that reads:

'Celtic' crossbills differ in bill size from other crossbill species found in Britain, and just like native Scots, they have also been found to have a distinct Scottish accent or call.

And it's well known that Scots (or Homo edinburgensis as scientists call them) are a distinct species. The RSPB press release has more about the three types of crossbills:

Scotland's conifer woods are home to three types of crossbill -

* the common crossbill (with a small bill best suited to extracting seeds from the cones of spruces)

* the parrot crossbill (with a large bill suited to extracting seeds from pine cones)

* and the Scottish crossbill (with an intermediate bill size used to extract seeds from several different conifers).

All three are similar in both size and plumage, and DNA tests have showed that the birds are genetically similar, casting some doubt on the Scottish crossbill's status as a distinct species.

In fact, you can't really tell the different kinds apart just by examining them:

Although the three species differ in average bill size, the actual differences are small and cannot be used reliably in the field by ornithologists to identify crossbills.

But wait:

The calls, though, can be distinguished by sonograms, or sound pictures, made up from recordings. Crucially, this provides the basis for a method to survey crossbills and, for the first time, gain a clear picture of their numbers and distribution in Scotland.

So the RSPB did a "long term field study" in which they captured 46 mated pairs of crossbills of various types, to learn "if the birds mate with those with a similar bill size and call, and whether young Scottish crossbills inherit their bill sizes from their parents".

Results showed that, of 46 pairs of different types of crossbills caught, almost all matched closely for bill size and calls. In other words, the different types of crossbills were behaving as distinct species.

The small number of 'mismatched' pairs was too few to suggest that the different types are not species, but enough to account for their genetic similarity. The fact too that young crossbills had bill sizes similar to their parents showed that they inherited their bill sizes, and also supports the species status of Scottish crossbills.

Gee, I bet you could use a similar technique to demonstrate that various ethnic groups in the U.S. are separate species.

The RSPB press release tells us that "Scottish crossbills (as identified by bill size) also have quite distinct flight and excitement calls from other crossbills", but unfortunately, neither the press release nor its replication at the BBC tells us what crossbills' calls are like in general, and how the Scottish-dialect version differs. The Scottish crossbill page on the RSPB website says that it has "[a] 'chup chup' call with a fluty quality", whereas the common crossbill has "[a] loud 'chip chip' call; a warbling, twittering song", whereas the parrot crossbill has "[v]ery similar calls to crossbills, but thought to give a distinctive deep ‘kop-kop’ and ‘choop choop’".

Since the RSPB has no equivalent of the International Phonetic Alphabet at its disposal, I'm puzzled about the difference between the Scottish crossbill's "chup chup" and the parrot crossbill's "choop choop". We want spectrograms and scatter plots! (There are audio samples on the RSPB site, but only one recording per "species". I presume that the RSPB's field study has been published somewhere, but I haven't tracked it down yet.)

The RSPB's "long term field study" now must be supplemented with a larger and longer field study:

The next steps in the Scottish crossbill study are to find out its population size and habitat requirements.

With the current estimate of 1,500 birds for its global population, being little better than a guess, a detailed survey is crucially important to put together the right conservation and management measures to protect and conserve it.

Dr Jeremy Wilson, head of research for RSPB Scotland said, 'Clarifying the status of the Scottish crossbill as a distinct species, and devising a survey method based on the bird's calls are exciting steps forward.

'We hope to carry out the first full survey of the numbers and distribution of Scottish crossbills in 2008, after which we will be better placed to understand how best to manage conifer woodlands in Scotland to secure the future of a bird found nowhere else in the world.'

Another, more cynical, argument for the RSPB's conclusion begins to suggest itself. Echoing Max Weinreich's observation that "a language is a dialect with an army and a navy", we might suggest that "a species is a phenotypic variant with a protected habitat". (Or take a look at the Wikipedia article on species for a sketch of the reasons why the concept "species", up close, is just about as contested as the concept "language".)

But if you ask me, the crossbills are getting their "accents" from those Scottish birders. At least, that's what the cow-dialect theory tells us.

[Hat tip: Edward Wilford.]

[Update: a few minutes with Google Scholar establishes that crossbills are indeed among the bird species that exhibit vocal learning. Thus P.C. Nundinger, "Call Learning in the Carduelinae", Systematic Zoology, 28:3 270-283 (1979). From the abstract:

Experiments and field observations document vocal imitation in six cardueline species representing four genera. Flight call learning was found in all birds studied; learning of many other call types was observed in two genera. Additional evidence extends call learning to other carduelines bringing to eight the total number of genera in which call learning has been observed. Call learning is perhaps characteristic of subfamily Carduelinae, and the taxonomist should consider the possibility that learning may affect the patterns of all adult cardueline vocalizations. The taxonomic value of cardueline calls in particular and passerine calls in general is re-examined in light of this extensive call learning.

[emphasis added]

From the body of the article, commenting on an experiment with call sharing in a pair of captured white-winged crossbills (Loxia leucoptera), who were mated by the experimenter's choice rather than their own:

I conclude that the call sharing exhibited by this pair of Loxia leucoptera is not due to chance but is the result of vocal imitation, and that vocal imitation affects most, or even all, of the call types in this species.

J.G. Groth ("Call matching and positive assortative mating in Red Crossbills", Auk, 1993) studied appalachian crossbills (Loxia curvirostra), and offers a plot of calls from members of 24 mated pairs:

Fig. 1 Audiospectrograms for call notes of 24 pairs (labelled A-X) of crossbills in Virginia. For each pair, call note of male illustrated on left and female on right. Short horizontal marks along vercial axes are at 2, 4, and 6 kilohertz, and width of each box represents 140 msec.

The overall conclusion of this paper is that

These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that distinctive forms of crossbill represent reproductively isolated groups (i.e. species).

However, his main evidence is there is a very wide range of body and bill sizes and shapes, and the shapes and sizes of mated pairs are highly correlated. The call types also match, but as he observes:

The Appalachian crossbills also showed a pattern of assortative pairing based on acoustic characters, but this observation is trivial because call matching was a prerequisite for identification of birds as mates. No information is available on the structure of the calls of these birds before they became associated with their mates.

Indeed, the very wide range of exactly-shared call types makes it seem unlikely that the call sharing is entirely genetic, though Groth's experience with captive crossbills was different from Nundinger's:

In two captive pairs with mates having intitially different call structures that produced nests and successfully fledged young, the mates never matched each other's flight calls.

(though this may have been because of the age at which the birds were captured). The role of genetics vs. vocal learning is left unclear:

The process by which crossbills choose their mates is not known. Bill size correlates with conifer preference in crossbills, and calls could function as signals giving information on morphology and, therefore, habitat preference, of individuals. A question that remains is whether vocalizations, visual assessment of morphology..., habitat preferences, or combinations of these and/or other cues provide the basis for mate choice in crossbills.