April 30, 2007

LOL?

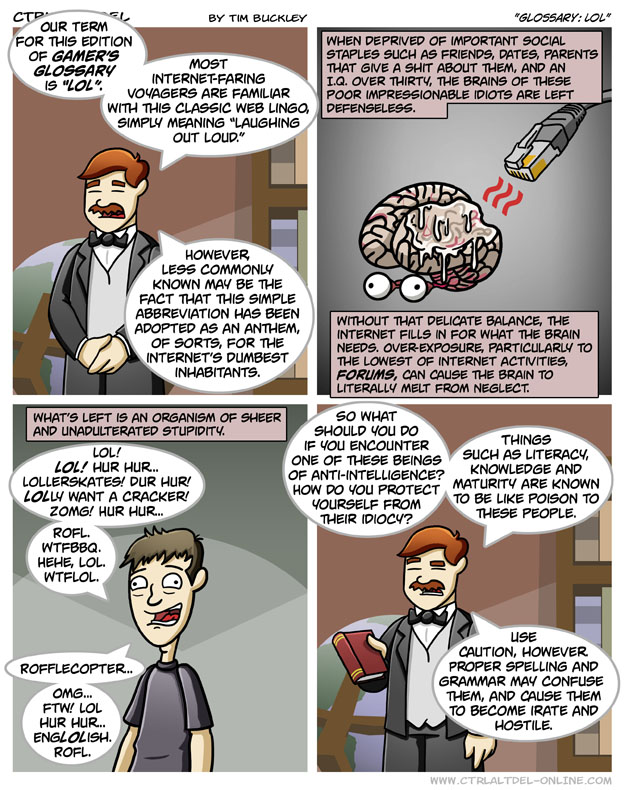

I'm afraid that I don't get it. Maybe the idea is that old-tyme slang involved new meanings for old words, like "cool", while "LOL" is an altogether new word? But there are plenty of antique terms made from initialisms, like AWOL or FUBAR. So it's not that, but what?

[Please, don't write to explain to me what LOL means, or how it's one of many recent initialisms associated with keyboarded communication, or even that this particular one originally comes from usenet if not before, rather than from the IM and texting cultures that have adopted it. I already know that. What I don't get is why someone would think that this is a new linguistic development, more like a new language than like just another example of the well-established phenomenon that gave us SNAFU and many others.]

[John Cowan wrote:

I think it's just the same old same old "degenerate youth" business. No special explanation needed.

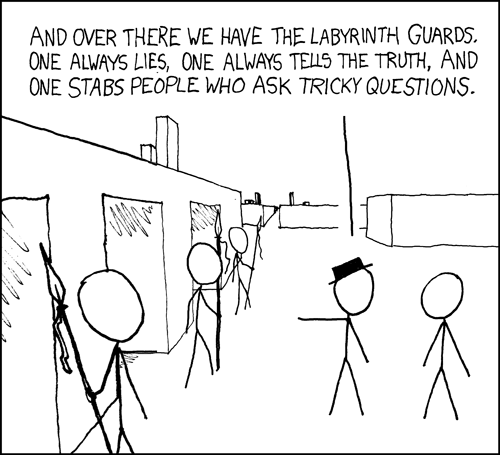

And by way of elaboration, John sent a link to this comic:

Well, I know that "No one ever went broke underestimating the intelligence of the American people", as H.L. Mencken said, but "unshelved" is a comic strip. An internet comic strip about librarians, for cripes sake, which I expect to be at least a bastion of common sense, if not a beacon of intellect. I'm disappointed.]

April 29, 2007

Narthex

I was doing some reading the other night. In this case the book was Hesiod's Theogony. Okay, I admit that I'd already finished my nightly crossword puzzle to help ward off Alzheimers, but Hesiod used a term that seemed really odd. I'm sure you're all familiar with Hesiod but this part had to do with Prometheus, who had just deceived his father, Zeus, by playing a trick on him. As Hessiod records the story, Prometheus:

Playing tricks on Zeus, such as stealing his private stash of fire, was a serious no-no in those days so Zeus decided to deal harshly with his naughty son (the obvious lesson: don't mess with God). So what was this punishment? He created woman. I suspect you already know that at this point in mythical history the world was populated entirely with males, so Zeus's punishment had serious implications for...well, we won't get into that. But the Genesis account of man's fall suggests pretty much the same thing.

My point here is that I always thought a narthex was the anteroom of a church and it seemed odd that Zeus would hide his fire in such a place. But according to the translator's notes, a "narthex is a giant fennel." I know that fennel is a herb of the carrot family that's cultivated for its foliage and aromatic seeds and that it's used in soups and salads for flavoring but, just the same, I checked my handy OED definition of "narthex." Lo and behold, the OED defines "narthex" as:

Sounds good so far but the OED went on to call a "narthex" a yellow flowered umbelliferous plant with leaves and stalks used in salads and soups with the seeds used as flavoring, derived from the Latin "feniculum," meaning hay.

So how did this word, dervived from Latin "feniculum," meaning hay, ever shift from being a hollow container with a hard and apprently fire-proof outer cover that was appropriate for Zeus to use to carry and conceal fire? I enjoy reading Hesiod and I'm perfectly willing to accept what he says about ancient mythology, but it still seems strange that a plant of the carrot family, or hay, or a small case used to hold unguents, or a herb used to flavor soups and salads, also could once have been a giant-sized, hollow, rock-hard, fire-containing structure. More interestingly perhaps, how did "narthex" then make that long and mysterious semantic journey, eventually becoming today's church vestibule?

Language is a truly wonderful thing. No wonder so many people study it.

[Update: Whenever I stick my neck out and express my ignorance, I can be sure that there is an alert Language Log reader out there to straighten me out. And sure enough, Greek scholar Craig Russell informs me that "narthex" is an Ancient Greek word for a giant fennel, different from a regular fennel. It has a long, straight and sturdy hollow stalk, perhaps like bamboo. It was used as a walking stick and was likely familiar to the people of that time. Since it was hollow, it could be used to store things. Russell tells me that Alexander the Great is said to have brought over the papyrus text of Homer inside a narthex stem. So other than the flammable properties of the plant, Hesiod must have been on to something. Russell opines that this hollow stalk could have been used for carrying small things, like powder or liquids and maybe even the unguents used in church ceremonies and it may be that unguents were stored in the church vestibule, leading us to the modern meaning. Thanks, Craig.]

Asterisking and other orthographic rituals

Kerim Friedman and Omri Ceren wrote to draw my attention to the proposal by David at Ironic Sans to "Uncensor the Internet with Greasemonkey" (4/27/2007) by removing certain cases of typographical bleeping:

Is there a way for us to avoid all this f****ng unnecessary self-censorship littering the internet?

There is now. I've created the "Uncensor the Internet" script for Greasemonkey (a Firefox plug-in that lets you add all sorts of useful functionality to your web browser, available here). If you're running Firefox with the Greasemonkey plug-in, just install this script, and see all the foul language that people are pretending they don't use.

But as David points out, those people aren't really "pretending they don't use" the words in question. Instead, they're performing a curious sort of ritual acknowledgment of a social consensus that the words are in some way dangerous, or at least problematic:

There's an article on-line from Money Magazine called "50 Bulls**t Jobs." That's right. Bulls**t. With those two asterisks in there. Come on. We know what word they mean. So why not just say it? If they think we're adult enough to be reminded of the word, why don't they think we're adult enough to see the actual word? (The article is based on a book by the same name, but without the asterisks)

Oh, I know. It's the kids. They might be reading. Sh*t. I didn't f*cking think of that. It would be terrible if they would see the word "Bulls**t" in print, but it's okay for them to see it with the asterisks, right? They'll have no idea what that means.

As David ironically demonstrates, all the writers and readers involved in this enterprise know exactly what words are being written. Are the asterisks just an attempt to obey the letter of a prohibition while violating its spirit? This is certainly true of the verbal gymnastics that the FCC requires on the radio, and it's also how I used to see the asterisks that David's script removes. But recently, I've come to the conclusion that they're really a kind of ritual orthographic gesture, which is often not required by any formal policy, but still serves a social purpose. When you put in an asterisk or two, while leaving the identity of the word obvious in context, you're using (or mentioning) the word, while at the same time saying to your readers "yes, I acknowledge that this word has a special status".

That's how I interpret the quoted remarks of Lisa Dale, the principal of Benson High School in Omaha, Nebraska, who got in trouble for green-lighting a section of the student paper that discussed usage of the word "nigger":

"I probably wouldn't, however, looking back -- we'd use the asterisk," Dale said of the paper's decision to spell out the N-word.

The whole point of the published discussion was that the word is problematic; but failing to asterisk or otherwise disguise the word itself still shocked or offended some readers. The offense seems to be a symbolic one, like failing to salute the flag, or to cover or uncover your head at certain times and places, or stand or sit at certain points in a ritual. Or, perhaps, this is like the risk of magical damage that some people believe is created by praising someone or remarking on good fortune, which then must be mitigated by the gesture of "knocking on wood" or making the mano cornuta. Many people who are not really superstitious, in any serious sense, may still perform these rituals half-ironically.

Taboo avoidance or mitigation comes in several other flavors as well . In between the notes from Kerim and the note from Omri came this compact and efficient communiqué from Justin Mansfield, under the Subject heading "Typographical bleeping":

2 things:

1) aposiopesis

2) gxddbov xxkxzt pg ifmk

Aposiopesis is the traditional name for "the rhetorical device by which the speaker or writer deliberately stops short and leaves something unexpressed, but yet obvious, to be supplied by the imagination, giving the impression that she is unwilling or unable to continue. It often portrays being overcome with passion (fear, anger, excitement) or modesty." The "something unexpressed" can be a more-or-less obvious obscene epithet -- "why, you son of a ..." -- and in such cases, the ellipsis can accomplish a sort of taboo avoidance.

A more complex and aesthetically satisfying type of taboo-avoiding aposiopesis is the Miss Susie/Lucy rhyme. Here the performer and the audience share knowledge of taboo words, which are contextually determined, sometimes even performed, and then transformed into harmless alternatives, generating much group glee on grade-school playgrounds:

Miss Lucy had a steamboat

The steamboat had a bell

Miss Lucy went to heaven

and the steamboat went to

Hello operator

Get me number nine

If you disconnect me

I will kick your fat

Behind the refrigerator ...

As for gxddbov xxkxzt pg ifmk, this famous phrase is discussed in the American Heritage Dictionary as follows:

The obscenity fuck is a very old word and has been considered shocking from the first, though it is seen in print much more often now than in the past. Its first known occurrence, in code because of its unacceptability, is in a poem composed in a mixture of Latin and English sometime before 1500. The poem, which satirizes the Carmelite friars of Cambridge, England, takes its title, "Flen flyys," from the first words of its opening line, "Flen, flyys, and freris," that is, "fleas, flies, and friars." The line that contains fuck reads "Non sunt in coeli, quia gxddbov xxkxzt pg ifmk." The Latin words "Non sunt in coeli, quia," mean "they [the friars] are not in heaven, since." The code "gxddbov xxkxzt pg ifmk" is easily broken by simply substituting the preceding letter in the alphabet, keeping in mind differences in the alphabet and in spelling between then and now: i was then used for both i and j; v was used for both u and v; and vv was used for w. This yields "fvccant [a fake Latin form] vvivys of heli." The whole thus reads in translation: "They are not in heaven because they fuck wives of Ely [a town near Cambridge]."

This is a sort of 15th-century version of the usenet-era rot13 convention. The idea in both cases seems to have been that the cipher is transparent and easy to decode -- many news readers used to have a rot13-function accessible via a single keystroke, as I recall, and "one letter back" is easy to calculate in your head -- but still, it isn't readable without a modest bit of explicit effort, so that no one can complain of having been offended unless they took the trouble to put themselves in the way of it to start with.

The typographical bleeping business (e.g. by substituted asterisks for one or two letters) is not like this, since recognition of the intended word is effortless and automatic. Instead, it seems to be a less elitist and more lexically-specific version of the practice described by Herbert Halpert in "Folklore and Obscenity: Definitions and Problems", The Journal of American Folklore, 75(297), 1962:

Earlier in this century when anthropologists were busy collecting American Indian myths and tales in text, they usually published them in a museum or university anthropological series, with English translations. Invariably, when you get to the lustful doings of Coyote or some other trickster figure, or to version of the toothed-vagina motif, the English translation suddenly lapses into Latin.

The practice is older than that, I think -- I've seen it in 19th-century documents as well. In any case, it doesn't actually hide the content of the passage from anyone likely to be reading it (though it has no doubt sent some teenagers to look things up in Lewis & Short). Among those who have learned what words like paedicare meant, using a shared alternative language is like adding asterisks: a ritual way of acknowledging that the material has a special status. The tradition of rendering phrases in Latin dealt mainly with taboo concepts, however, where merely switching to a more formal register or even using English euphemisms wouldn't be enough, while asterisking focuses on taboos associated with particular words.

[A list of other LL posts on vocabulary taboos is here.]

[Peter Sattler writes:

I, too, do not know when the "dirty stuff in Latin" technique began, but I did immediately recall some passages from William Bradford's "Of Plymouth Plantation." Take, for example, this 1642 discussion of criminal sexual activities:

Qest: What sodmiticall acts are to be punished with death, & what very facte (ipso facto) is worthy of death, or, if ye fact it selfe be not capitall, what circomstances concurring may make it capitall?

Ans: In ye judiciall law (ye moralitie wherof concerneth us) it is manyfest yt carnall knowledg of man, or lying wth man, as with woman, cum penetratione corporis, was sodomie, to be punished with death; what els can be understood by Levit: 18. 22. & 20. 13. & Gen: 19. 5? 2ly. It seems allso yt this foule sine might be capitall, though ther was not penitratio corporis, but only contactus & fricatio usq ad effusionem seminis....

Of course, this shift to Latin may have as much to do with the nature of legal discussions as sexual discussions.

A more amusing example emerges repeated in the diary of Samuel Pepys, who discusses his amorous adventures in an odd mishmash of Spanish, French, and Latin — yet in a fashion that seems just as determined to leave the "hidden" material clearly visible. Here are two examples from 1668, pulled off the Net:

[I] Dressed and had my head combed by my little girle, to whom I confess je sum demasiado kind, nuper ponendo saepe mes mains in sus dos choses de son breast. Mais il faut que je leave it lest it bring me to alguno major inconvenience.

[A]nd there she came into the coach to me, and yo did besar her and tocar her thing, but ella was against it and labored with much earnestness...at last did yo did make her tener mi cosa in her mano, while mi mano was sobra her pectus, and so did hazer with grand delight

I wish I had the Pepys here (I almost typed "in hand"), because I seem to remember that, in parts, the diarist would reserve Latin for the dirtiest passages. But these passages don't seem to support that memory.

]

[Andrew Gray comments:

What we read of Pepys is decoded *already* - he wrote in a cryptic shorthand to ensure privacy, and therefore he didn't really need to obfuscate anything to protect the casual reader. He "encoded" both normal English and the mishmashed passages alike, I believe. The mismash was probably just intended to confuse his wife if she stumbled across it - it's immediately apparent to an educated cosmopolitan reader (or, even, an educated Cosmopolitan reader), but quite possibly would have been meaningless to her. (Or perhaps she would have managed it perfectly well and he was just cocky about his cleverness - either is plausible!)

As to the Latin, Pepys has been reissued in about a dozen versions, each purporting to be "full" and each just omitting slightly less material than the previous one, as people grew a little more accepting of the dirty bits. (There's a good discussion of this in 'Dr Bowdler's Legacy', to digress slightly). It strikes me as entirely possible that one otherwise expunged edition kept a lot of the obfuscated Italian/French/Spanish bits, but just rewrote them in Latin in order to have the desired effect... and, of course, it would look perfectly normal when you encountered one of these Latinised passages.

]

[Another reader adds:

I am far, far, from a Pepys scholar. But what I understand from the preface to the Latham and Matthews edition of his diary is that he used one of the existing systems of shorthand in his day -- like writing in Gregg or Pitman in 1925: obscure to the common reader, but hardly a cipher.

Is there any indication whether the shorthand was merely a time- or effort-saving convenience, or was also used with the purpose of foiling casual readers? ]

Arabs and camel words: go ahead, just make stuff up

‘Saudi tribe holds camel beauty pageant’ says the headline over a Reuters news story by Andrew Hammond (filed Friday, April 27, 9:23 AM ET). It begins thus:

GUWEI'IYYA, Saudi Arabia (Reuters) - The legs are long, the eyes are big, the bodies curvaceous.

Contestants in this Saudi-style beauty pageant have all the features you might expect anywhere else in the world, but with one crucial difference — the competitors are camels.

And so attuned am I to the ways of the journalistic world and its snowclones that when Marilyn Martin sent me this story I found that I could actually predict the drift of what would come up in the following paragraph before I even looked. Sure enough — I never doubted it for one moment that it would be there (though I would not have been able to guess the number):

The camels are divided into four categories according to breed -- the black majaheem, white maghateer, dark brown shi'l and the sufur, which are beige with black shoulders. Arabic famously has over 40 terms for different types of camel.

Of course it does, of course it does. And I for my part have over 57 different words for lazy journalists who repeat snowclones about vocabulary size in languages they know absolutely nothing about and cite warrantless lexeme-count figures taken from sources they cannot name or even vaguely recall.

What gets up my nose is not so much that lexical traveler's tales of this sort are so often false. Some seem to be sort of true. At least for Somali (not too far away from where Arabs live) Mark Liberman actually listed 46 genuine camel words, earning only sarcasm from me, but winning the enormous gratitude of the blogosphere, which has joyously repeated the figure many times.

And it's not even that these unsubstantiated myths about lexical counts mostly float around without backing — unsourced and undefended because journalists know that no one (except me on Language Log) will call them on claims about languages, regardless of how ridiculous the claims are.

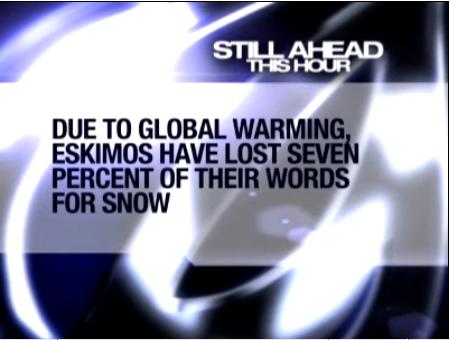

No, what gets me most about these lexeme-count claims is that they are presented as if they were profound and significant and clearly supportive of exoticizing claims about far-away nomadic peoples like Arabs and Eskimos, when in fact even if they were true they would be utterly unsurprising.

Think how many names for breeds of dogs you could list. Why? Because we (in the West) have been domesticating and breeding types of dog for thousands of years and they mean something to us. Think how many names of paint colors you've seen on paint shop color charts. Think how many makes and models of cars you could name. It is totally boring and obvious that one will have a variety of specialized terms for things that one's culture has taken a long-term interest in.

The difference is, your knowledge of 40 different words for automobile models is not passed around as a gem of wisdom about the English language and worldview. For the Arabs and their camel terms or the Eskimos and their snow words, things are very different: the lexical count becomes a putative nugget of insight into their mysterious nature as a people.

And with numbers made up entirely at random, that's the other thing that drives me up the wall. Among those appearing on the web before such phrases as "words for camel in Arabic" (as you can easily verify) are: 9; 20; 40; 160 (this one is quite common); 400; 1,000; 3,000; 5,000; "a gajillion"; and of course various different quantifiers like "several", "numerous", "many", and "a whole bunch".

One of the most strangely specific is by P. L. Heath in Philosophical Quarterly, 1955 (in a review of Ernst Cassirer's The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms, Volume 1, JSTOR link here). Heath says (and he may be paraphrasing Cassirer): "Arabic, for instance, has 5744 words for different kinds of camel and none for camels in general."

Of course it does, of course it does. Exactly five thousand seven hundred and forty-four. Or perhaps nine; or forty; or four hundred; or a thousand; whatever. Don't stop to figure out a defensible number, just babble on about it as if the random number you picked was important and well backed up by linguistic research.

Maybe if you write some kinds of stuff for Reuters they may want to do fact-checking; maybe some of what you write for Philosophical Quarterly will be subjected to refereeing; but not if it's about size of subsets of the nouns in a randomly chosen language spoken in an area of the world where they still have "tribes". On that topic you will never be queried; so go ahead, just make stuff up.

[Update: Lane Greene has pointed out to me that although one can imagine someone being unable to evaluate a claim he read somewhere about 5,744 words for camel in a language he could not read, it is easy to answer the question of whether there is a single general word for camel. Just pick up an etymological dictionary. German Kamel and English camel come from Arabic jamal and Hebrew gamal via Greek kamelos, meaning of course "camel". To encounter the 5,744 figure and swallow it may be regarded as a misfortune; to overlook the existence of jamal in Arabic looks like carelessness.

It could perhaps be argued that jamal only refers to male camels, so it isn't fully general. But in that case, what about ’ibil, which is general as regards sex (though it can only be used in the plural). For a more informed discussion of the story about camel words in Arabic, see Lameen Souag's excellent blog post on the topic, which makes the point that we shouldn't equate "Arab" with "highly expert Arab camel breeder who knows all the relevant technical vocabulary associated with that trade". That's what I feel people are so often doing when they tell these many-words-for-X tales.]

April 28, 2007

Singular they on Facebook

Greetings yet again from the Youth and Popular Culture desk at Language Log Plaza. The singular they phenomenon is usually Geoff Pullum's beat (his most recent report is here), but we've just come across another set of examples that we thought we'd report directly.

When you login to Facebook, you're presented with a "News Feed" that lets you know what your Facebook friends are up to: what groups they've joined, what they've got planned for the weekend, who else they've become friends with -- anything they want to let you know. Facebook users can leave their sex unspecified if they like, and if they do so, singular they is used to refer to that user. So, for example, a news item from a specified-male Facebook friend will show up on my news feed like this:

John Doe added "fried chicken" to his favorite foods.

An item from a specified-female Facebook friend will show up like this:

Jane Doe added "pizza" to her favorite foods.

And an item from an unspecified-sex Facebook friend will show up like this:

Kim Doe added "burgers" to their favorite foods.

[ Comments? ]

Everybody are doing it

Another example for the collective collection (verb agreement division) -- Alec Baldwin, as quoted by Alessandra Stanley, "Under Fire, an Actor Lashes Back With a Plan", NYT, 4/28/2007:

"Everybody who works in tabloid media are people who are filled with self-hatred and shame," he said. "And the way that they manage those feelings is that they destroy the lives of other people and reveal your secrets."

To complicate matters further, when he says "your" he means "my". It's the inclusive your. Or something like that.

[Update -- Peter Metcalfe writes:

He's referring to himself in the second person. My previous experience with this phenomenon was a politician who had a billboard with the legend "Your country needs you".

Nice, but not quite the pattern I had in mind, though I guess you could interpret it that way. What Baldwin did was to use the generic second person in order to make his own position more appealing, by putting the hearer, at least pronominally, into Baldwin's situation. The odd thing about this particular example is that the group that "your" refers to is the same as the group referred to by the immediately preceding phrase "other people" -- and both are really attempts to raise to generic status what Baldwin thinks happened to him.

Here's another recent (but more conventional) example of blame-shifting with generic "you". The quote is from a college student facing felony charges after he and some others allegedly forced their way into an apartment in order to avenge a friend who had been punched (Pete Bosak, "6 PSU players face felony charges; 20 more may face questioning", Centre Daily, 4/28/2007):

Dozens of teammates answered Scirrotto's call for help, according to court documents.

Hayes said the contingent of football players went to the Meridian II thinking they were going to Scirrotto's aid when, police said, his scuffle with the three victims had been over for almost 45 minutes.

"You got to do what you got to do," Hayes allegedly told police when asked whether they went to the apartment to seek revenge for Scirrotto being roughed up earlier. "We went down to protect."

Police said six of them forced their way into the apartment and at least two of them attacked Imle and anyone who tried to stop them. Almost 20 other football players were outside, police said.

]

Garfield's interpreter

The Garfield strip from 4/23/2007:

I wonder how lolcats has affected the Garfield industries? Does the competition lower sales, or is this a product like addictive drugs, where increased supply (I assume) just leads to increased demand?

April 27, 2007

Contingency-table literacy: no biomedical researcher left behind?

According to Anne Underwood, "It's Almost Too Good for Us to Believe", Newsweek, 4/26/2007

Prostate cancer is the second leading cancer killer among men, after lung cancer. The American Cancer Society projects that in 2007 there will be 219,000 new cases and 27,000 deaths. Yet detecting the disease early has always been problematic. The only blood test available now—a test for prostate-specific antigen (PSA)—is not good at distinguishing malignancies from benign prostate enlargement (BPH). And it's useless for separating aggressive cancers from others that are so slow-growing they will likely never cause problems.

But a new blood test, described this week in the journal Urology, could change all that. In a study of 385 men, the new test was able to distinguish BPH from prostate cancer, and it pinpointed men who were healthy, even when their PSA levels were higher than normal. It also did the reverse—singling out men with cancer, even when their PSA levels were low. It may also distinguish cancer confined to the prostate from cancer that has spread beyond the gland. And it has the potential to dramatically reduce the number of biopsies performed every year.

The body of this Newsweek article is an interview with Dr. Robert Getzenberg, the head of the lab at Johns Hopkins where the test was developed. As a guy entering the prostate-cancer time of life, I'm glad to see diagnostic progress. But as a teacher of pattern-classification algorithms, I was less happy to see a spectacular scientific misstatement in the interview as published:

How reliable is the test? Did you get any false positives?

About 3 percent of the time, when the test was positive, there was no prostate cancer there.

This was too good for me to believe. So I checked, and from Table 2 of the paper (Eddy S. Leman et al., "EPCA-2: A Highly Specific Serum Marker for Prostate Cancer", Urology 69(4), April 2007, Pages 714-720), I learned that the result was actually this: among 232 control samples from people without prostate cancer, 7 (or about 3%) tested positive. So a better way to answer the question would have been: "About 3 percent of the time, when there was no prostate cancer there, the test was positive".

Is this just a quibble, or does it matter? Well, a reasonable conclusion from Dr. Getzenberg's statement would be that a positive result from his group's test means that you have prostate cancer, 97 times out of 100. But as we'll see below, the true probability that you have prostate cancer given a positive test result (and assuming that the test's specificity really is 97%) is something more like 1.5%. (Given the 92% specificity actually claimed by the published paper, it would be about 0.6%).

The reason for that spectacular difference -- not 97%, but 1.5% or 0.6% or thereabouts -- is that the great majority of men don't have prostate cancer . Therefore, even a small false-positive rate will produce many more false positives than true positives. So a brutally honest answer to the interviewer's question might have been: "If our results hold up in larger trials, we anticipate that about 1.5% of men who test positive would actually have prostate cancer."

I guess it's possible that Dr. Getzenberg lost track of this elementary statistical point. It's also conceivable that Newsweek garbled his interview transcript. I'd hate to think that Dr. Getzenberg misspoke on purpose, influenced by the fact that "Johns Hopkins Hospital is working with Onconome Inc., a biomedical company based in Seattle, to bring the test to market within the next 18 months" ("Test improves prostate cancer diagnosis", Science Daily, 4/26/2007), and the royalties from a test that might be given every year to every man over 40 in the developed world would be stupendous.

Why was the published false positive rate really 8% rather than 3%?. Leman et al. (Table 2) give two different numbers for the "specificity in selected population[s]" of the new test. ["Specificity" is defined as TrueNegatives / (FalsePositives + TrueNegatives) -- if there are no false positives, then the specificity is 100%.]

The second of these "selected populations" is the set I just cited -- 232 people without prostate cancer, among whom there were 7 false positives, for a specificity of 225/232 = .9698. This set is described as "control groups that included normal women, as well as various benign and cancer serum samples". It's a bit odd to calculate the specifity of a prostate-cancer test on a sample including women, who don't have a prostate to start with. And so for a comparison to the traditional PSA test for prostate cancer, the "selected population" was different -- 98 men without prostate cancer, among whom there were 8 false positives, for a specificity of 90/98 = .9183.

This was still a lot better than the results of the PSA test, which gave 34 false positives in the same sample, for a specificity of 64/98 = .6531. But 92% isn't 97%, and 92% is the number that Dr. Getzenberg's group gives in the Urology paper:

Using a cutoff of 30 ng/mL, the EPCA-2.22 assay had a 92% specificity (95% confidence interval 85% to 96%) for healthy men and men with benign prostatic hyperplasia and 94% sensitivity (95% confidence interval [CI] 93% to 99%) for overall prostate cancer. The specificity for PSA in these selected groups of patients was 65% (95% CI 55% to 75%).

What's much more important is that the specificity (whether it's 97% or 92% or whatever) can be a very misleading number. It's the proportion of people without the disease who get a negative test result. But if you get a positive test result from your doctor, what you really want to know is the "positive predictive value", i.e. the proportion of people with positive test results who really have the disease. In this case, 97% specificity probably translates to a positive predictive value of 1.5%, whereas 92% specificity translates to a positive predictive value of about 0.58%.

In order to think about such things, people need to learn to analyze contingency tables. If I could wave a magic wand and change one thing about the American educational system, it might be this one.

Here's an example of a 2x2 contingency table for binary classification (adapted from the wikipedia article on "sensitivity"), set up to interpret the results of a medical test:

| The Truth | ||||

| Disease | No Disease | |||

| The Test Outcome |

Positive | True Positive | False Positive (Type I error) |

→ TP/(TP+FP) Positive predictive value |

| Negative | False Negative (Type II error) |

True Negative | → TN/(FN+TN) Negative predictive value |

|

| ↓ TP/(TP+FN) Sensitivity |

↓ TN/(FP+TN) Specificity |

|||

In filling out a table like this, it's not enough to know what the test does on selected samples -- we need to know what the overall frequency of the condition in the population is. Leman et al. dealt with a test sample of 100 men with prostate cancer, and two control samples without prostate cancer: one of 232 men and women, and another of 98 men. But those sample sizes were chosen for their convenience, to include roughly equal numbers of positive and negative instances. What would the numbers look like in a random sample of men?

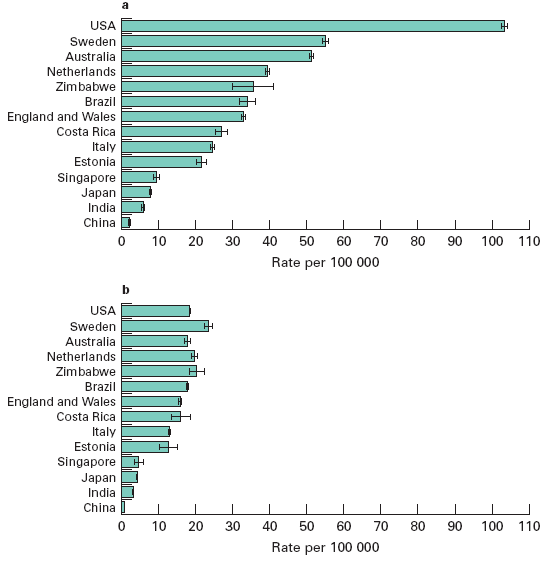

I'm not sure, but these plots from M. Quinn and P. Babb, "Patterns and trends in prostate cancer incidence, survival, prevalence and mortality. Part I: international comparisons", BJU International, 90 (2002), 162-174, suggests that the rate of prostate cancer is somewhere between 50 and 100 per 100,000:

[Plot a is prostate cancer incidence, and plot b is prostate cancer mortality, both "age-standardized using the World standard population". I assume that the large difference in incidence between the U.S. and the next three countries, with much smaller differences in mortality, suggests that either the U.S. over-diagnoses, or Sweden, Australia and the Netherlands under-diagnose, or both.]

Remembering that "sensitivity" is the proportion of the genuine disease cases that the test correctly identifies as positive, i.e. the ratio of true positives to the sum of true positives and false negatives; and "specificity" is the proportion of disease-free people that the test correctly identifies as negative, i.e. the ratio of true negatives to the sum of true negatives and false positives; then:

Given a disease rate of 50 per 100,000, and a test with sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 92%, out of a random sample of 100,000 men, we'll have

Men with the disease = TruePositives + FalseNegatives = 50

Men without the disease = TrueNegatives + FalsePositives = 99,950Sensitivity = TP/(TP+FN) = 0.94, so TP = 0.94*50 = 47

Specificity = TN/(FP+TN) = 0.92, so TN = 0.92*99,950 = 91,954FN = 50-47 = 3

FP = 99,950 - 91,954 = 7,996

Now we can fill the table out with counts and percentages:

| The Truth | ||||

| Disease | No Disease | |||

| The Test Outcome |

Positive | True Positive n=47 |

False Positive (Type I error) n=7,996 |

→ TP/(TP+FP) Positive predictive value =0.58% |

| Negative | False Negative (Type II error) n=3 |

True Negative n=91,954 |

→ TN/(FN+TN) Negative predictive value =99.99+% |

|

| ↓ TP/(TP+FN) Sensitivity=94% |

↓ TN/(FP+TN) Specificity=92% |

|||

Given these assumptions, if you get a positive test result, the probability that you actually have cancer (the "positive predictive value") is 47/(47+7996), or 0.005843591 , or a bit less than 6 chances in 1,000. If the background rate is 50 per 100,000, the fact that you're now at 584 chances per 100,000 is worth worrying about -- your odds are more than 10 times worse -- but it's not as bad as 92,000 or 97,000 chances per 100,000.

If you get a negative test result, the probability that you don't actually have cancer is 91954/(91954+3), or 0.9999674. That's comforting, but if you don't take the test at all, your chances of being cancer-free are 99950/100000 =0.9995.

(You can redo the analysis for yourself, assuming other population rates for the disease. For example, if the incidence is 100 per 100,000, then the positive predictive value of the test would be .94*100/(.94*100+.08*99900), or about 1.2%.)

Similar analyses of the similar contingency tables are come up in information retrieval (where "precision" is used in place of "positive predictive value", and "recall" is used in place of "sensitivity"), in signal detection theory (see also the discussion of ROC curves and DET curves), and in general, in all branches of modern pattern recognition, AI, computational linguistics, and other fields where algorithmic classification is an issue.

Algorithmic classification is playing a bigger and bigger role in our lives -- and medical tests, though important, are only part of the picture.There's spam detection. There's biometric identification, both for identity verification and in forensic or intelligence applications. There are those programs that flag suspicious financial transactions, or suspicious air travelers. There's the integration of "intelligent" safety features into cars and other machines. And many others.

Details aside, this process is essentially inevitable. It's driven by ubiquitous networked computers, cheap networked digital sensors, more and more storage of more and more digital data, and advances in -omic knowledge and analysis.

The science and technology behind algorithmic classification techniques are varied and complex, but in the end, interpreting the results always comes down to analyzing contingency tables. And some of the relevant mathematics can get complicated, but the basic analysis of error types and error rates doesn't require anything beyond 6th-grade math and a willingness to learn some jargon like "specificity". To make informed personal and political choices in the 21st century, you'll need at least that much.

It's pretty clear that the Newsweek editors aren't there yet, or they would have corrected this portion of the interview. If Dr. Getzenberg wasn't misquoted, his command of basic contingency-table concepts is also shaky. I can testify that this stuff is generally news to American undergraduates, and even to most graduate students entering programs in psychology, biology, linguistics and computer science.

I don't expect that any of our presidential candidates will make contingency-table literacy part of their campaign platform. But maybe they should.

[Fernando Pereira writes:

To add insult to injury, the bio community is divided on the meaning of the term "specificity". Biostats use the meaning you give, but in bioinformatics, especially in gene prediction, "specificity" = TP/(FP+TP)

In other words, exactly what others refer to as "precision" or "positive predictive value". All the more reason to be sure that readers are clear about what the proportions (and counts) in the contingency table are really like.]

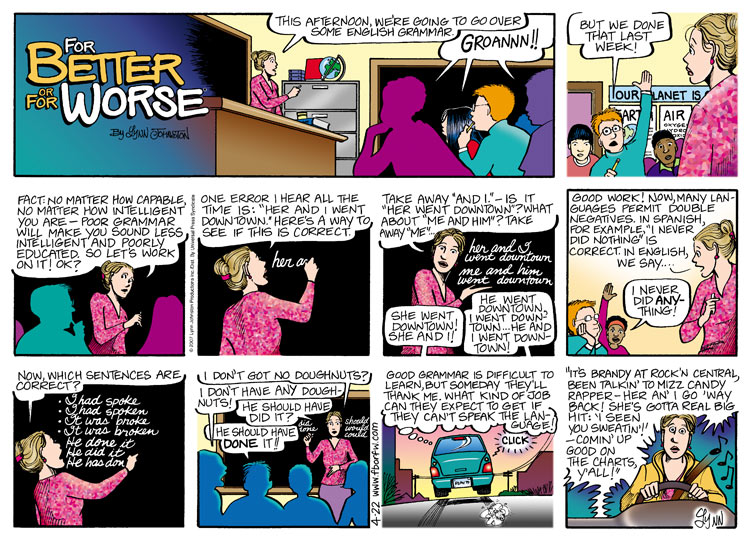

The Problem With Today's Youth

People are always going on about the problem with today's youth. The headline this morning in our local newspaper is "Bad Behaviour up in Schools". A hint is to be found in the same newspaper, which contains an advertising supplement from Canadian Tire, an institution which here in Canada may well rank above the Queen in public esteem. In 2006 it ranked first in reputation among Canadian companies (report.) On the front page is an advertisement for a mountain bike. The model? "The Hooligan". What a great message for the kids. Next I suppose we'll have "The Vandal", "The Looter", and "The Rapist". What planet do marketing people come from?

April 26, 2007

The N-Word in Omaha

Benson High School, a public high school founded in 1904, was recently designated by the Omaha [Nebraska] Public Schools as "a Magnet Center for Academic Research and Innovation". However, its first appearance in the national news didn't work out in a way that pleased OPS officials. The trigger was the March 2007 issue of the school newspaper, the Benson Gazette, which included a four-page section on The N-Word.

The issue was distributed on April 10, and higher-level school bureaucrats quickly intervened to denounce the newspaper, to withdraw it from distribution, and to put the school's principal on administrative leave (Lynn Safranek, "Students' frankness sets of OPS uproar", Omaha World-Herald, Saturday 4/14/2007):

The Omaha Public Schools on Friday condemned a four-page section in the Benson Gazette, distributed Tuesday, that tackled students' use of the word "nigger." The section presented the viewpoints of black and white students and staff, including the school's dean of students and athletic director.

The school's principal, Lisa Dale, was put on administrative leave Friday. OPS officials declined to say why.

Calls came into OPS offices this week expressing concerns about the content of the section, said Luanne Nelson, an OPS spokeswoman. Some staff members from throughout the district, plus some Benson community members and students, were offended, she said.

On Friday, the newspaper was removed from Benson High's Web site as OPS announced an investigation into the matter. The district will take "appropriate action" when the investigation is completed, according to a statement.

"The Omaha Public Schools has never condoned and cannot support the actions which recently resulted in the inappropriate articles published in the Benson High Gazette," the statement read. "Unacceptable decision-making by staff has violated the standards set forth by the Omaha Public Schools to appropriately guide and educate our students."Nelson said Dale's status is pending the results of an investigation by OPS's human resources department. Dale could not be reached for comment.

Benson students and parents reacted with shock and disappointment to the news that Dale had been placed on leave and that OPS disapproved of the articles.

I haven't seen the "standards set forth by the Omaha Public Schools to appropriately guide and educate our students", so it may well be true that permitting this newspaper to be published was a straightforward violation of those standards. If so, it seems to me that the standards ought to be modified, because the section strikes me as a responsible attempt to explore a difficult subject, one that clearly comes up many times every day at a school like Benson.

And I can't easily come up with a better short document to recommend for outsiders to read, to help them understand this curious aspect of the linguistic anthropology of contemporary America. Reading about the OPS reaction helps to understand other dimensions of the situation, which is why I've decided to post about it.

The World-Herald article continues:

The four-page section included news stories and a transcript of a round-table classroom discussion. An editorial and two editorial cartoons produced by the newspaper staff poked fun at the dual meanings of the word and criticized the ability of one race, but not others, to use the word without repercussion.

Nelson, the OPS spokeswoman, said, "There is no question that the students had a valid, spirited discussion regarding this topic." She said, however, that a high school newspaper may not be an appropriate forum, "because, as a printed piece, it can be misinterpreted."

Benson senior Sarah Swift, the paper's editor in chief, disagreed.

"I think a newspaper is the perfect forum," said Swift, who is white. "Why would we have newspapers at all? It may make people uncomfortable, but you can't talk about things that people are always OK with. We can't just ignore the bad things and hope they go away."

Perhaps because of the national attention ("Student paper's use of epithet sets off uproar", AP, reprinted in JournalStar of Lincoln, Nebraska), or perhaps because there wasn't really any violation of policies, it didn't take long for the school authorities to back off, at least with respect to the principal's job status (Susan Szalewski, "Principal reinstated at Benson after flap", Omaha World-Herald, Monday 4/16/2007):

Lisa Dale, the principal of Benson High School who was placed on administrative leave after the school's student newspaper published a racially charged special report, has been reinstated.

Dale will return to work today.

Reached at her home Sunday, Dale said Omaha Public Schools officials determined that she could better serve the school and community by returning to her post. She did not elaborate.

Whatever may have happened since, it's been going on below the journalistic radar. In possibly-related news, however, the Omaha Reader recently announced that

Declaring they’re fed up with concealed weapons laws and early bar closing times, Benson business owners have declared Benson its own nation-state with plans to secede from the larger Omaha metropolitan area. The group, armed with toy rifles, funny hats, musical instruments and loads of spirit have even set a date.

“We declare April 1 as Benson Independence Day,” said J. Asintheletter, whose family has been in Benson since before it was cool. “We want everyone to know that they can be themselves here.”

I infer that the rebels are against both concealed weapons and early bar closings -- the concealed-carry business apparently refers to passage of a new state law and repeal of a city ordinance, (Nancy Hicks, "Concealed weapons will be legal in Omaha", JournalStar, 7/18/2006); Nebraska's legal bar hours are 6:00 a.m. to 1:00 a.m., though perhaps Omaha has some local regulations as well.

There's nothing about alcohol in the March issue of the Benson Gazette, but an editorial on p. 8 discusses the fact that 52% of students don't feel safe in school, although the concealed-carry law doesn't apply there:

After being released from first block on the morning of Monday, March 5, students trudged on to their second class of the day - not quite ready to be back at school after a four day weekend. It was at approximately 9:27 a.m that a large gang related fight erupted in the east wing of Benson, stirring the curiosity of onlookers and preventing others from getting to class on time.

As if this was not enough ammunition for “water cooler” talk between students (and even staff), a student was suspended for bringing a gun to school. News stations covered the story, there was a brief moment of shock and awe which passed as fast as it came, but life went on as usual the next day.

The truth is, the student who brought the gun was not the first, nor was he the last person to enter Benson with a firearm. The only difference in this instance is that he was caught.

In general, both the school newspaper and the school's web site leave me very favorably impressed with the school and its students -- the OPS central office should be proud.

[Update -- Here is a report of a school board meeting about the issue: "School Board Meeting Packed With Opinions: 'N' Word At Center of Controversy", KETV-7, Wednesday 4/18/2007. And an earlier article ("Benson Principal Returns To Work", KETV-7, 4/16/2007) that ]

that indicates considerable support for Lisa Dale:

Students crowded around Dale at lunch on Monday. Student Nick George and fellow classmates said they were prepared to protest if Dale was fired. "It says, 'Support Ms. Dale. Free Press,'" said George, showing off a T-shirt that was made. "The back says, 'Ms D and newspaper are No. 1.'"

KETV.com's online discussion of the newspaper saw overwhelming support for the principal and the students, too.

In fact, as far as I can see, all of the 60 or so comments seem to support the students and the principal. The 4/16/2007 article quotes the principle as accepting responsibility"

Dale said on Monday it was a tumultuous few days for her.

"Not be here in the place that I love -- that, for me, is my heart and soul. The thought of that has been very difficult," Dale said. "The big question was: Did I see the articles before they went into print? And I did and so I take full responsibility."

but also as offering an interesting olive branch (fig leaf?) to the school board:

Dale said some good did come of the newspaper.

"It created conversations that allowed us to say, 'You know, even when it's casual, even when it's friendly, it's not appropriate,'" the principal said.

Dale said she learned a lesson.

"I probably wouldn't, however, looking back -- we'd use the asterick," Dale said of the paper's decision to spell out the N-word.

(I'm guessing that the non-standard spelling of asterisk was contributed by the reporter.)]

Virginia, who said they would come

Another remarkable singular they example collected by Nick Reynolds (he also collected this beautiful case). His yoga teacher was waiting for some students to show up for an informal jujitsu class, and so far only one, Steve, had shown up, so the teacher said to Steve:

Virginia isn't here, who said they would come; Chris isn't here, who said they would come; and Devin isn't here, who said they would come.

Virginia was the only female involved, and the teacher knew that. So the use of singular they (for it is singular: the teacher was not talking about Virginia having claimed that some group of other people would come) was not motivated by any possible lack of knowledge about gender, or by the neutrality of an indefinite antecedent like anyone. The speaker (going a bit beyond my usage — I don't find the above example fully grammatical) was using the supplementary relative clause who said they would comeas the way to express the property "x said x would come" regardless of the antecedent to which it is attached — even if that antecedent is a proper name (which I personally do not find grammatical, but keep in mind this kind of case, which seems different). Interesting further evidence of the aggressive spread of singular they in modern colloquial American English (and and English in other parts of the globe too, I'm told).

April 25, 2007

Kitty Pidgin and asymmetrical tail-wags

Anil Dash has a fun post arguing that "Cats Can Has Grammar" (4/23/2007). Surveying lolcats and related phenomena, he quickly passes over the snowclone "I'm in UR X Ying your Z" and the whole Invisible X phenomenon, and focuses on "the newly dominant lolcats, of the family 'I Can Has Cheezeburger?'". He observes that

Anil Dash has a fun post arguing that "Cats Can Has Grammar" (4/23/2007). Surveying lolcats and related phenomena, he quickly passes over the snowclone "I'm in UR X Ying your Z" and the whole Invisible X phenomenon, and focuses on "the newly dominant lolcats, of the family 'I Can Has Cheezeburger?'". He observes that

The rise of these new subspecies of lolcats are particularly interesting to me because "I can has cheezeburger?" has a fairly consistent grammar. I wasn't sure this was true until I realized that it's possible to get cat-speak wrong.

Incorrect kitty pidgin jumped to my attention the first time I saw a reference to Dune being used with a lolcat image. The caption on the linked version of the image, "The spice must flow." is fine, if not particularly cat-like. But the caption on the version I saw first was much more verbose: "I are dunecat. I controls the spice, I controls the universe." Besides being an awkward attempt at overexplaining the punchline (I've never read Dune or seen the film, but the joke is obvious) this was just all wrong. The fact that we can tell no cat would talk like this shows that kitty pidgin is actually quite consistent

I feel really out of it, having no experience with lolcat and no intuitions about its captional norms. After a bit of investigation, though, I've decided that I don't feel badly enough about this to undergo the lolcat immersion required to change it.

Anil continues:

... I suggested this consistent grammar for lolcats could be a "cweeole". Knowing a bit more about such things now, I realize this isn't a creole but more likely a pidgin language, used to help cats talk to humans. And since "pidgin" is already a cutesy spelling of a mispronunciation, there doesn't seem to be any really cute way to rename it to reflect its uniqueness. "Kitty pidgin" might be the closest thing we have to a name for this new language.

Isn't this more like kitty baby-talk, long used for cutesy interactions with cats and small dogs, most memorably by certain P.G. Wodehouse characters? This 1922 passage illustrates the same type of "idiosyncratic conjugation" that Anil has identified in lolcats (of course minus the 4chan and l33t-speak overlays):

Vincent Jopp flushed darkly. Even the strongest and most silent of us have our weaknesses, and my employer's was the rooted idea that he looked well in knickerbockers. It was not my place to try to dissuade him, but there was no doubt that they did not suit him. Nature, in bestowing upon him a massive head and a jutting chin, had forgotten to finish him off at the other end. Vincent Jopp's legs were skinny.

"You poor dear man!" went on Mrs. Jane Jukes Jopp. "What practical joker ever lured you into appearing in public in knickerbockers?"

"I don't object to the knickerbockers," said Mrs. Agnes Parsons Jopp, "but when he foolishly comes out in quite a strong east wind without his liver-pad----"

"Little Tinky-Ting don't need no liver-pad, he don't," said Mrs. Luella Mainprice Jopp, addressing the animal in her arms, "because he was his muzzer's pet, he was."

I was standing quite near to Vincent Jopp, and at this moment I saw a bead of perspiration spring out on his forehead, and into his steely eyes there came a positively hunted look. I could understand and sympathize. Napoleon himself would have wilted if he had found himself in the midst of a trio of females, one talking baby-talk, another fussing about his health, and the third making derogatory observations on his lower limbs. Vincent Jopp was becoming unstrung.

Meanwhile, over at the New York Times, Sandra Blakeslee reports on some research on the interpretability of tail wagging in dogs: "If You Want to Know if Spot Loves You, It's in His Tail", 4/24/2007. The message is not the old news that tail-wagging expresses feelings, or that more vigorous wagging expresses stronger feelings, but the new information that the feelings' nature determines which side of the dog gets more of the wag. This has been discovered by a team of Italian veterinarians, and reported in Giorgio Vallortigara et al., "Asymmetric tail-wagging responses by dogs to different emotive stimuli", Current Biology, 17(6), 20 March 2007, pp R199-R201. They found

... some unexpected and striking asymmetries in the control of tail movements by dogs: differential amplitudes of tail wagging to the left or to the right side associated with the type of visual stimulus the animals were looking at.

Here's a graphical summary of their results:

And their interpretation goes like this:

Davidson [3] suggested that the anterior regions of the left and right hemispheres are specialised for approach and withdrawal processes, respectively. Although Davidson's hypothesis was developed in the context of human neuropsychology, approach and withdrawal are fundamental motivational dimensions which may be found at any level of phylogeny [4].

In our experiment, stimuli that could be expected to elicit approach tendencies, such as seeing a dog's owner, were associated with higher amplitude of tail wagging movements to the right side (left brain activation) and stimuli that could be expected to elicit withdrawal tendencies, such as seeing a dominant unfamiliar dog, were associated with higher amplitude of tail wagging movements to the left side (right brain activation). (As to the cross-over of descending motor pathways, in dogs the rubrospinal tract is the predominantly volitional pathway from the brain to the spinal cord; the pathway decussates just caudal on the red nucleus and descends in the controlateral lateral funiculus; fibres of the rubrospinal tract terminate on interneurons at all levels of the spinal cord; see [5].)

Reference [3] is R.J. Davidson, Well-being and affective style: neural substrates and biobehavioural correlates, Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 359 (2004), pp. 1395–1411.

So if you really want to know what your dogs are feeling, anyhow on the approach/avoidance dimension, watch what side they wag on. Translation into babytalk is strictly optional, as far as I'm concerned. What I want to know it, do dogs themselves pay attention to this potentially-informative aspect of their fellows' signaling?

And, of course, how about cats' tail-lashing?

[Nancy Wright writes:

Yesterday, one of the regular inmates over at www.icanhascheezburger.com was posting a tutorial on how to speak it: "LOL-Kitteh as a Second Language".

Actually, now that I think of it, that may have been the investigation you did that made you decide you didn't want "to undergo the lolcat immersion required to change [your lack of experience]."

It was one of the steps on the path, certainly. Though I suspect the author may be the Pedro Carolino of the ICHC idiom.]

More Language Log posts on lolcats:

"Kitty Pidgin and asymmetrical tail-wags", 4/25/2007

"Lolbrarians", 5/5/2007

"L337 KATZ0RZ", 5/12/2007

"Linguist macros?", 5/18/2007

"Lol-lexicography", 5/18/2007

"Lol Vincit Omnia", 5/27/2007

"Loop until kthxbye", 5/30/2007

"Accelerando molto con micino", 5/31/2007

"Amplifying 'faint signals' from the alpha geeks who are creating the future", 6/2/2007

"Lolxicographers", 6/7/2007

]

April 24, 2007

They call it stormy Lundi

Among the funniest responses to the results of last weekend's French presidential election, this clever snowclone -- or perhaps we should say, o-clone -- comes from the cartoonist Barrigue, published by Le Matin in Lausanne:

Fabio Montermini, who sent in the link as a follow-up to my earlier post about "Political hypocoristics" (4/18/2007), explains that the expression "Métro, boulot, dodo", meaning "subway, work, sleep", is a common way for Parisians to express the tediousness of modern urban life. Presumably, "Métro Sarko Ségo" is a way of expressing disappointment that the centrist François Bayrou didn't make it to the second round; in any case, it frames the run-off as political same-old same-old, unimpressed by the fact that the winner this time will be the first French president born after WWII, etc., etc.

The response "Comme un lundi" means "Like a (typical) Monday".

1595 is available, but 1975 isn't

You can blame Thor Power Tool Company v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, or Kahle v. Gonzales, or Murphy v. Everybody. But whoever or whatever is responsible, it's bizarre.

In yesterday's post on Ezra Pound at PENNsound ("God's own Englishman with a tube up his nose", 4/23/2007), I mentioned Derek Attridge's 258-page monograph "Well-Weighed Syllables: Elizabethan Verse in Classical Metres", Cambridge University Press, 1975. I bought it for $22.50 in 1975, and remembered it well enough to cite it in my post. Looking it up on line, I discovered that it's out of print, but amazon.com offers us four used copies for between $175 and $179.98, while at alibris.com, there's one copy for $179.93. AbeBooks.com comes up with nothing.

Here's the dust-jacket blurb, copied by hand from my copy:

Sidney's statement in his Apology for Poetry that quantitative verse on the Latin model is more suitable than the accentual verse of the English tradition 'lively to expresss divers passions, by the low and lofty sound of the well-weighed syllable', is only one of numerous assertions of the superiority of classical over native metres made by English scholars and poets during the Renaissance, stretching from Roger Ascham some twenty years earlier to Ben Jonson some fifty years later. Yet this widely-held view appears to modern eyes a perverse eccentricity, and the substantial body of English verse in classical metres produced in this period by a host of writers has long baffled commentators by its apparent disregard of elementary metrical principles.

Dr. Attridge argues that the impulse to write vernacular poetry in classical metres was not an aberration, but a natural outcome of the way in which Latin was read and taught during the Renaissance, giving rise to a conception of metre very different from that which we take for granted today. This enables us to understand not only the low estimate of English accentual verse held by many educated Elizabethans, but also the particular forms which the experiments in English classical verse took.

Dr. Attridge also relates the quantitative movement to broader trends in Elizabethan taste (of which it is a particularly illuminating manifestation), and shows how the sudden decline of the movement was part of a more general change in sensibility at the end of the sixteenth century.

Apparently market forces don't apply to university presses. Given that the marketplace sets the value of used copies of this work at $175 or so, you'd think that Cambridge University Press would sell digital copies for some lesser sum, perhaps making their whole backlist available on a subscription basis to libraries, as EEBO does with works much longer out of print; or perhaps they could turn their out-of-print works over to a just-in-time publisher, as MIT Press has done.

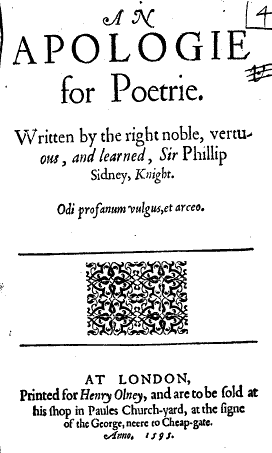

Ironically, Sir Philip Sidney's views on English metrics, originally published in 1595, are easily available to us via Early English Books Online:

And from the OCR'ed version we can even snarf the passage from which Attridge took his title:

Vndoubtedly, (at least to my opinion vndoubtedly,) I haue found in diuers smally learned Courtiers, a more sounde stile, then in some professors of learning: of which I can gesse no other cause, but that the Courtier following that which by practise hee findeth fittest to nature, therein, (though he know it not,) doth according to Art, though not by Art: where the other, vsing Art to shew Art, and not to hide Art, (as in these cases he should doe) flyeth from nature, and indeede abuseth Art.

But what? me thinks I deserue to be pounded, for straying from Poetry to Oratorie: but both haue such an affinity in this wordish consideration, that I thinke this digression, will make my meaning receiue the fuller vnderstanding: which is not to take vpon me to teach Poets hovve they should doe, but onely finding my selfe sick among the rest, to shewe some one or two spots of the common infection, growne among the most part of VVriters: that acknowledging our selues somwhat awry, we may bend to the right vse both of matter and manner; whereto our language gyueth vs great occasion, beeing indeed capable of any excellent exercising of it. I know, some will say it is a mingled language. And why not so much the better, taking the best of both the other? Another will say it wanteth Grammer. Nay truly, it hath that prayse, that it wanteth not Grammer: for Grammer it might haue, but it needes it not; beeing so easie of it selfe, & so voyd of those cumbersome differences of Cases, Genders, Moodes, and Tenses, which I thinke was a peece of the Tower of Babilons curse, that a man should be put to schoole to learne his mother-tongue. But for the vttering sweetly, and properly the conceits of the minde, which is the end of speech, that hath it equally with any other tongue in the world: and is particulerly happy, in compositions of two or three words together, neere the Greek, far beyond the Latine: which is one of the greatest beauties can be in a language.

Now, of versifying there are two sorts, the one Auncient, the other Moderne: the Auncient marked the quantitie of each silable, and according to that, framed his verse: the Moderne, obseruing onely number, (with some regarde of the accent,) the chiefe life of it, standeth in that lyke sounding of the words, which wee call Ryme. VVhether of these be the most excellent, would beare many speeches. The Auncient, (no doubt) more fit for Musick, both words and tune obseruing quantity, and more fit liuely to expresse diuers passions, by the low and lofty sounde of the well-weyed silable. The latter likewise, with hys Ryme, striketh a certaine musick to the eare: and in fine, sith it dooth delight, though by another way, it obtaines the same purpose: there beeing in eyther sweetnes, and wanting in neither maiestie. Truely the English, before any other vulgar language I know, is fit for both sorts: for, for the Ancient, the Italian is so full of Vowels, that it must euer be cumbred with Elisions. The Dutch, so of the other side with Consonants, that they cannot yeeld the svveet slyding, fit for a Verse. The French, in his whole language, hath not one word, that hath his accent in the last silable, sauing two, called Antepenultima, and little more hath the Spanish: and therefore, very gracelesly may they vse Dactiles. The English is subiect to none of these defects.

Too bad we can't resurrect Henry Olney and put him to work monetizing the CUP backlist. Or perhaps we need to resurrect Thomas Jefferson and put him to work refreshing the tree of liberty with the blood of copyright lawyers.

[It should go without saying that this would be purely intellectual blood, and no lawyers (who are as likely to be fine human beings as anyone else is) are to be harmed in the process.]

April 23, 2007

Stupid prophylactic public statement blather

I would just like to say that I deny any wrongdoing in this matter. Although I am sorry about what has occurred, and I am sorry that some people feel the way that they do, I continue to maintain that I have done nothing wrong. When all the relevant facts are fully disclosed, I believe my innocence will be clear. I fully believe that I can continue to be effective in this office, in which I am proud to serve. I am determined to fight these allegations and have no plans to resign. Those who for political reasons have sought to damage my reputation, and that of a blameless young woman with whom my relationship has at no time been improper, must bear responsibility for the hurt they have caused to me and my family. It would be inappropriate for me to comment further this time, as I have been advised me not to discuss this matter further in public until the facts can be fully presented. But I believe that ultimately I will be fully vindicated. We plan, at the proper time, to refute all of the disgraceful allegations about us that have been spread by the more irresponsible sectors of the media. In conclusion, let me just say that I am most grateful for the love and support of my family at this difficult time. Thank you.

Hurting people loved here

No, this isn't an example created by the Church Sign Generator -- it's the sign outside my neighborhood Baptist church (and polling place) in North Park.

No, this isn't an example created by the Church Sign Generator -- it's the sign outside my neighborhood Baptist church (and polling place) in North Park.

In introductory linguistics courses we linguists often use the tired old "visiting relatives can be tedious" (or "boring", or "a pain", or what have you) as an example of a certain kind of ambiguity: are we talking about visiting our relatives, or are we taking about the relatives who visit us? I like the example on this church sign better: do my neighborhood Baptists love people who experience pain, or do they love people who cause others to experience pain? (Or: do they love acts that cause others to experience pain?)

All of God's children are presumably loved equally, but I'm fairly certain that the ambiguity of this example was not intentional. If it were, I'd expect to find more about it on the church's website -- it would be too clever to pass up.

[ Comments? ]

Comments on "The Interpreter"

[Guest post by Vera da Silva Sinha and Chris Sinha]

Below is a letter sent to The New Yorker in response to an article entitled “The Interpreter” by John Colapinto which appeared in The New Yorker of April 16 2007. The article is a lengthy and interesting account of Dan Everett's work on the Pirahã language of Amazonia. Our letter draws on our own visit to the Pirahã and on our fieldwork with another Amazonian indigenous community. We do not know if, our how much of, the letter will be published, but we think readers of this site might be interested. The work on time in Amondawa discussed below is reported in an article which will imminently be submitted for publication.

We are an anthropologist and a psychologist who visited the Pirahã in January 2006, at the behest of FUNAI (the Brazilian Indian Agency) and the municipality of Humaitá, in the State of Amazonas (Brazil). We were asked to do so because (we were informed) the Pirahã community had requested the provision of schooling. Our visit (by boat) took place in the company of FUNAI, FUNASA (health agency) and municipal officials, and an interpreter. The request for our visit was issued because one of us (Vera) has experience of establishing an indigenous language school in another Amazonian community, the Amondawa, who speak a Tupi Kawahib language unrelated to Pirahã. We communicated with Dan Everett about our visit, and during our stay we experienced at first hand the cultural patterns described by John Colapinto, and by Everett in his article in Current Anthropology. Not having knowledge of the Pirahã language, and not being confident in attempting to understand it via an interpreter, we made no attempt to confirm or disconfirm Everett’s linguistic analysis. Everett’s data and arguments are compelling, and they are fully consistent with the activities, dwellings, speech, songs and dance that we observed. The Pirahã language and culture seemed very distinctive in comparison to other indigenous Amazonian communities of which we (notably Vera) had prior experience. Nevertheless, we question the extent to which the Pirahã are quite as spectacularly unique and “different” as is suggested in your article.

To begin with, there exists, as well as so far uncontacted indigenous groups in Rondônia State (Brazil), at least one other monolingual Amazonian community, the Zuruhuã, who resist interaction with strangers. Many other indigenous groups have older community members who are monolingual. Monolingual speakers of other Amazonian languages are reluctant in just the same way as the Pirahã to engage in culturally “alien” tasks designed by linguists and psychologists and administered by strangers. So the first point we would make is that Tecumseh Fitch’s experiments may well be intrinsically, and not merely circumstantially, inconclusive. This critical point regarding what psychologists call cultural and ecological validity is not new, and is not confined to Amazonian cultures, but it bears reiterating.

Secondly, several of the characteristics described for Pirahã are common to other Amazonian (and other) languages, in particular the fusion of color terms with substance terms, the absence of quantifiers, a highly restricted numeral system, and the absence of grammatical tense. The last of these is particularly instructive. As long ago as the 16th century, Father José de Anchieta noted the absence of verbal tense in the Tupi languages of South America (unrelated to Pirahã).We have been researching, together with our colleagues Dr Wany Sampaio of the Federal University of Rondônia and Dr Jörg Zinken of our Department, the linguistic organization of time concepts in Amondawa. Our conclusion, in brief, is that this is radically different from that displayed in the languages most studied by linguists. It is not just a matter of a restricted number of terms, or of a lack of grammatical marking, but of a system based not on countable units, but on social activity, kinship and ecological regularity, that does not permit conventional “time-reckoning”. This is all the more striking when seen against the fact that the Kawahib system for space and motion, which we have also analyzed, displays a high degree of complexity. Space and motion terms are often “recruited” by languages to organize time, but not, it seems, by Amondawa, and we would hypothesize the same to be the case for Pirahã, as well as other Amazonian languages and their speakers. This does not mean that speakers of such languages have no time awareness, or that they are unable to talk about events and activities occurring in time. But they do not talk about time, or frame relations between events in terms of a notion of time separate from the events and activities.

These findings are very much in line with Dan Everett’s proposal that cultural practices and cultural norms influence both language structure and conceptual organization * and with his rejection of a one-way, Whorfian direction of influence from language to cognition. Cultures, however, change over time, often as a consequence of contact with other cultures, and we noted a particularly interesting instance of such change in the Pirahã. We had been asked to evaluate the plausibility of establishing an indigenous language school, and we had noted that Everett had written that the Pirahã saw no point in, and therefore were unable to, engage in basic literacy practices such as practising the writing of alphabetical characters. During our visit, we provided young Pirahã men with the wherewithal to do this, and at their request instructed them in how to do it. They did so readily and with a high level of competence, and we have audio-video recordings of them doing so. This occurred only after extensive discussions amongst the community members about whether or not they wanted a school (we have recordings of these discussions too).

This should remind us that cultures are not fixed entities, but dynamically changing ways of living together in changing circumstances. We do not mean to suggest that similarities between Pirahã culture and other Amazonian cultures make the Pirahã merely one among an undifferentiated mass of indigenous groups. All human cultures are unique, even if we can discern common patterns holding across different groups, and even though they are all products of our common humanity. Still less do we wish to downplay the distinctiveness, carefully documented by Dan Everett, of the Pirahã language. But to view just one group as the epitome of an exotic “otherness” is to fail to do justice to all the dimensions of the variation which still, today, can be encountered in the languages and cultures of the world. As Franz Boas maintained, the study of language is part of the psychology of the peoples of the world, and through comparative linguistics we can make progress in understanding both variation, and the limits on variation, of the human mind. For this reason we would find it regrettable either to treat Pirahã as just an isolated case study, or to reduce the significance of comparative language studies to the single issue of recursion.

Despite our general sympathy for Everett’s cultural approach to linguistics, there remains, to our mind, a problematic aspect to his account of Pirahã language and culture, namely his wide-reaching attribution of “gaps” in the linguistic system to “absences” in the culture. Our research on Amondawa conceptualizations of time leads us to the speculative conclusion that the absence -- as true of this Kawahib group as for the Pirahã -- of a cultural norm of accumulation (of food, seeds, money and goods in general) is related to the Amondawa notion of time as embedded in activity, kinship and seasonality. This is not the same, however, as saying that there is no domain of common, collective imagination of a time extending “outside” the present that is psychologically real for members of the Amondawa culture.

Whether or not we choose to call them “creation myths”, the Amondawa have narratives which both relate them to other groups and lend their own community a history and an identity. These narratives link the present day Amondawa to a time before “contact”, and in turn to the narratives that were told in those times. Everett maintains that such narratives simply do not exist for the Pirahã, but it may be that, in focussing on language structure, he has not “heard” the narratives; or that, faced with the competing narratives of Christianity, the Pirahã have chosen not to recount their own narratives to him. The Pirahã, it seems, both from Everett’s account and from our own observations, place little value on artefacts, or on the cultural transmission of the making of artefacts. Their material culture is, indeed, of an extreme simplicity. Yet the Pirahã could not survive without reproducing their culture. Could it be that in their art, in their language, and in their cultural identity, the Pirahã place more value on performance than on product? If so, they would not be dramatically different from many other human groups, merely at an extreme end of a continuum from material production to performative mimesis. If this, admittedly speculative, hypothesis has any truth, it might lead us to the conclusion that Dan Everett’s cultural linguistic analysis is not as far removed from Keren Everett’s observations about practices of cultural learning and teaching as he himself seems to think.

Finally, we should not forget that the Pirahã, like most minority indigenous groups, are very poor, and almost completely powerless in relation to the encroaching outside world. During our visit the people were hungry. Not just their way of life, but its foundation in their natural environment, is threatened. It would be good if a renewed interest in what we can learn from peoples like the Pirahã about the human mind were to be accompanied by an equal concern for helping them to acquire the resources necessary not just for survival, but for shaping their own future.

Vera da Silva Sinha, MA, MSc

Chris Sinha, PhD

University of Portsmouth

Department of Psychology

God's own Englishman with a tube up his nose