August 31, 2007

For glue the sex rubber mat

Would you buy a data switch whose assembly instructions include the phrase "For glue the sex rubber mat"? If your answer is "yes", [insert joke about Senate Republicans].

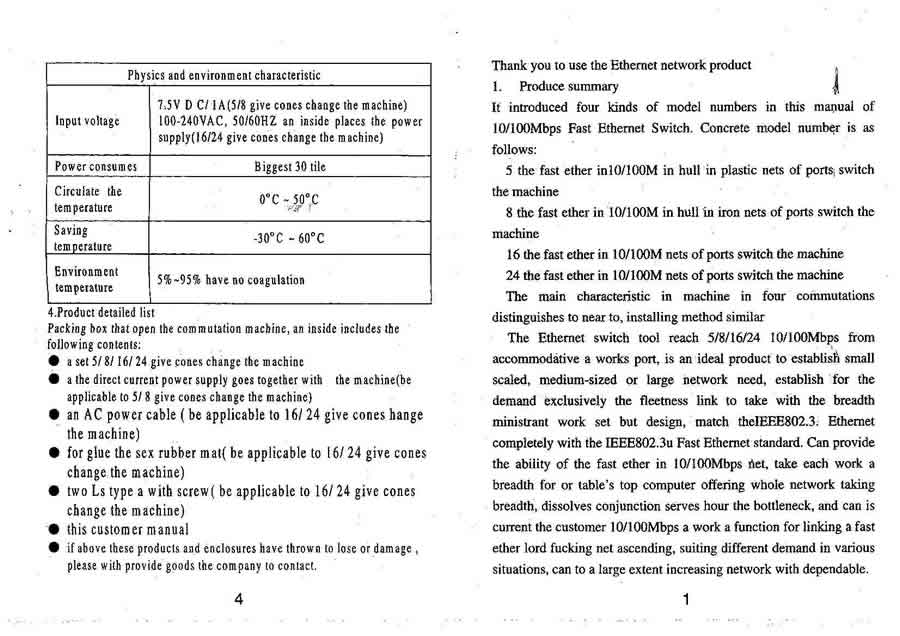

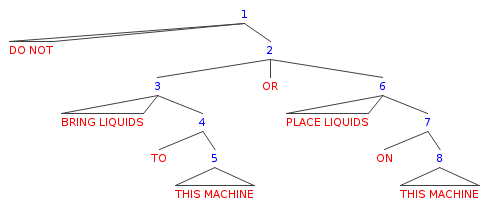

The datasheet that shipped with a Cisco switch, reported by Jake Vinson at Worse Than Failure, provides yet another example of translation from the Chinese by dictionary look-up. Some of the items are terms that might be English in some alternative universe, like "commutation machine" in place of "switch". Others are amusing mistakes that we've seen before, like "sex" in place of "type", which turned "one-time-type item" (i.e. "disposable item") into "a time sex thing" on an aisle sign at the Beijing Century Mart. Here it's "for glue the sex rubber mat", which I surmise might be a rubber-type pad to be attached in one of the machine's configurations:

(What do you suppose those "cones" are? "Modules", maybe?)

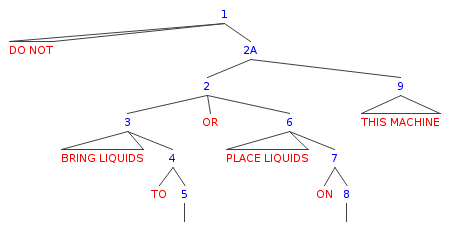

This next section features another old friend, in the phrase "a fast ether lord fucking net ascending". This learned discussion by Professor Victor Mair will give you a clue about how the f-word snuck in there -- and I suspect that the evocative "fast ether lord" is just a prosaic old "fast ethernet controller":

A larger sample of the datasheet is here:

Can it really be true that this is shipped with a Cisco product? It's understandable to see this kind of thing on a label or menu in a restaurant; it's more surprising to see it in the aisles of a hypermarket; but you'd think that a big-time multinational technology company would pay a little more attention. Richard Eng needs to point his Murciélago northwards, right away!

If you happen to have a copy of the Chinese original of this data sheet (unfortunately Jake Vinson's post doesn't specify the model number), please let me know.

[Update -- a google search for "give cones change the machine" turns up a number of things, including this. But "glue the sex rubber mat" comes up empty.]

[Update #2 -- Mel Wilson has a better idea about those "give cones":

It seems as though the product is one of a family of ethernet hubs or switches, with variants having 5, 8, 16 or 24 ports; so

5/ 8/ 16/ 24 give cones change the machine

would refer to the switch with the appropriate number of ports. 'Change' might have meant something like 'version', and 'give cones' somehow comes from 'sockets' or 'ports'.

I imagine the product comes with a sheet of pre-punched adhesive rubber feet to stick on the bottom.

Yes, but only for 16/24 give cones change the machine...

Seriously, I'm sure that Mel is right -- "16/24 give cones change the machine" must mean "the 16/24-port version of the machine".

Florian Weimer adds another piece of evidence:

I think the phrase "16/24 give cones change the machine" means "16 or 24 Ethernet ports". The smaller models with just 5 or 8 ports have got external power supplies; only the larger ones need an AC power cable.

Indeed -- add the insight that "change" means "version (of)" and the found poetry becomes a sensible and prosaic observation. ]

[Update #3 -- Brent Eades tries a clever experiment:

Use Google Translate, translate 'For glue the sex rubber mat' into Chinese (Simplified.)

Take the Chinese characters returned, then translate them back into English.

We get: "For adhesion of the rubber pad"

As for "give cones change the machine", repeating the above steps gives us "To change the tube machine". This is surprising; I would have thought Cisco had discovered semiconductors by now.

Finally, "fast ether lord fucking net ascending" gives us "Fast Ethernet main net or hell". Also surprising. And worrisome.

]

[Update 1/10/2008 - Lewis Jardine writes:

I think you've misread something: DailyWTF describes it as a 'Crisco switch' - i.e. a cheap generic one (Crisco being a brand of cooking oil). The same joke as when Homer goes to buy a 'Panaphonics' TV.

Maybe so -- in any case it has always bothered me that the scans did not include any brand indication. But just for the record, Crisco was basically and originally a brand of solid vegetable shortening, a lard substitute made by hydrogenating vegetable oil.]

Own, pone, poon, pun, pwone, whatever

Christopher Rhoads ("What Did U $@y? Online Language Finds Its Voice", WSJ, 8/23/2007) describes the the straw in the wind that broke the camel's back. Or is it the finger in the dike, for want of which the shoe was lost?

The central question is how to pronounce the characteristic typographical quirks of leetspeak:

Jarett Cale, the 29-year-old star of an Internet video series called "Pure Pwnage," enunciates the title "pure own-age." This is correct since "pwn" was originally a typo, he argues, and sounds "a lot cooler." But many of the show's fans, which he estimates at around three million, prefer to say pone-age, he acknowledges. Others pronounce it poon, puh-own, pun or pwone.

"I think we're probably losing the war," says Mr. Cale, whose character on the show, Jeremy, likes to wear a black T-shirt with the inscription, "I pwn n00bs." (That, for the uninitiated, means "I own newbies," or amateurs.)

Robert Hartwell Fiske is wheeled out for his traditional cameo, guarding the moon from wolves:

"There used to be a time when people cared about how they spoke and wrote," laments Robert Hartwell Fiske, who has written or edited several books on proper English usage, including one on overused words titled "The Dimwit's Dictionary."

But dude! Jarrett cares! And he's losing the war for the traditional pronunciation of "pwnage", while you mutter to yourself on the sidelines...

In fact, the article offers several examples of the strength of social norms, even if they're not exactly the norms that Fiske prefers:

"I pone you, you're going down dude, lawl!" is how Johnathan Wendel says he likes to taunt opponents in person at online gaming tournaments. Pone is how he pronounces "pwn," and lawl is how "LOL" usually sounds when spoken. Mr. Wendel, 26 years old, has earned more than $500,000 in recent years by winning championships in Internet games like Quake 3 and Alien vs. Predator 2. His screen name is Fatal1ty.

[...]

Mr. Wendel ... says he makes a point of using proper capitalization and punctuation in his online missives during competition. "It's always a last resort," says Mr. Wendel. "If you lose you can say, 'At least I can spell.'"

I'm hoping that he's expressing disdain for noobs who write "pone" instead of "pwn", and so on. I mean, a society is generally as lax as its language. A typical symptom of degeneracy is Roads' WSJ article itself, which includes quite a bit of dubious sound-influenced spelling:

In an episode of the animated TV show "South Park," one of the characters shouted during an online game, "Looks like you're about to get poned, yeah!" Another character later marveled, "That was such an uber-ponage."

From the point of view of substrantive linguistic description, my favorite part of the article deals with the evolving form, meaning and sound of "teh":

Those who utter the term "teh" are also split. A common online misspelling of "the," "teh" has come to mean "very" when placed in front of an adjective -- such as "tehcool" for "very cool." Some pronounce it tuh, others tay.

However, this seems to be incomplete and perhaps also partly false, at least according to the description in the wikipedia entry for "teh", which includes examples with verbs ("this is teh suck") and proper names ("teh Jeremy").

For more information about Pure Pwnage language and lifestyles, you might check out an episode.

[Update -- Alexis Grant writes:

I found your material on "teh" in "Own, pone, poon, pun, pwone, whatever" pretty interesting. One thing that stuck out at me was the quoted material 'such as "tehcool" for "very cool." ' No one I know would ever write "tehcool" without a space intentionally. (Actually, I don't know many people who use it at all anymore, but I used to. Now my friends make fun of me for sometimes using it.) So I wondered if that's a typo in LL, a typo in the article, or just a confusion of the author.

I was once referred to with the definite article in front of my name, and I took it as meaning that I was a notable and important instance of the name. I wouldn't say "teh cool" means "very cool", but something more like "an instance of cool that has high cool value". I wonder what units cool value has...

But I don't think Wikipedia has it right either: "that is best" and "that is the best" aren't related in the way that they seem to want them to be, and I don't think "teh [adjective]" really means that something is, e.g. the lamest, or that a person is the coolest (teh cool), but more "the essence of lame" or "the essence of cool".

Of course, it's hard for either Wikipedia or the WSJ to really pin down something that's still so much in flux, so I guess they should be excused for their confusions.

The string "tehcool" with no spaces is how it's rendered in the WSJ article. I don't know if that was a typo or Christopher Roads idea of how to spell it, but the WSJ is generally quite carefully edited, so I'd guess it was his choice. ]

August 30, 2007

Is Speaking Arabic Suspicious?

According to news reports, an American Airlines flight was delayed for several hours in San Diego Tuesday night when worried passengers overheard other passengers speaking Arabic. Ironically, the men speaking Arabic were returning to their homes in Detroit after training Marines at Camp Pendleton destined for Iraq. From a linguistic point of view, I guess the silver lining is that the worried passengers were able to identify Arabic.

This unfortunate incident reveals a common confusion of language, ethnicity, and religion. On the one hand, most speakers of Arabic are not terrorist material. On the other hand, potential Islamic terrorists speak many languages in addition to Arabic, including Urdu, Punjabi, Pashto, Persian, Indonesian, Malay, Turkish, Chechen, French, and English. A terrorist group with any intelligence will use people who do not attract attention to themselves.

It isn't surprising that hearing Arabic might make a passenger wonder, but you'd think that a moment's thought would overcome the impulse to notify the authorities in the absence of additional, more suspicious, behaviour. Indeed, insofar as the systems for detecting weapons and explosives work, there isn't really any reason not to allow people who actually do have terrorist sympathies to fly. As long as you know he has no weapons or explosives, you could let Osama bin Laden on the plane. I'd rather have him as a seatmate than many others - at least he doesn't drink.

Polysynthet-

This morning Mark posted a paragraph from Russell which read in part:

We are given to understand that a Patagonian can understand you if you say 'I am going to fish in the lake behind the western hill', but that he cannot understand the word 'fish' by itself. (This instance is imaginary, but it represents the sort of thing that is asserted.)I wonder if someone had been telling Russell about verb roots in polysynthetic languages, which often are what linguists call 'bound', i.e. cannot stand on their own as well-formed words. Rather, they must be inflected with one or more affixes to be well-formed utterances of the language.

Consider, for example, this description of Inuktitut verb stems from a translation of Elke Nowak's book Transforming the Images: Ergativity and Transitivity in Inuktitut, which allows a preview of itself to be nicely Googled up, hooray:

Inuktitut verbs can be formally described as nuclei that attain the status of a free-standing form by the addition of an inflectional ending containing information as to person, number, valence and mood. ...

(3) tukisi-paanga

. understand-3sS.1sO.tr.cond

. 'if s/he understood me'

The stem tukisi- means 'understand', all right, but it can't be uttered on its own; it's not a word. It might not be quite appropriate to say that an Inuktitut speaker wouldn't understand tukisi- on its own, but they certainly wouldn't take it as a meaningful utterance.

Even in English we have several roots with this property of needing an affix or two to make them independently utterable. In our case, they're mostly roots that came into English from a Romance language, but they're now a major subsystem in the vocabulary. Consider electr- for example. It shows up in electr-ic and electr-on and other words derived from those, but it is itself a unit of English morphology with a form and meaning. Or similarly the stem in anxi-ous and anxi-ety, or feroc-ious and feroc-ity, or frivol-ous and frivol-ity.

Those are just to give you the idea -- in some languages, all the roots and stems have this property of needing additional endings to make them possible utterances. The consequence is that, of course, you might not be able to say 'fish' by itself, without saying "my fish" or "I'm going fishing" or "Would you like to fish?"

Russell is right then to wonder what infants acquiring such languages do. In particular, do they invent uninflected forms of these bound roots to use as 'baby talk'? In fact, judging from this abstract, they don't. I don't have time to do any more investigating right now but I'd guess that the kids might use some frequent or default suffix as a generic way produce morphologically well-formed utterances until they've mastered the full complex system. I'll doublecheck on that and get back to you.

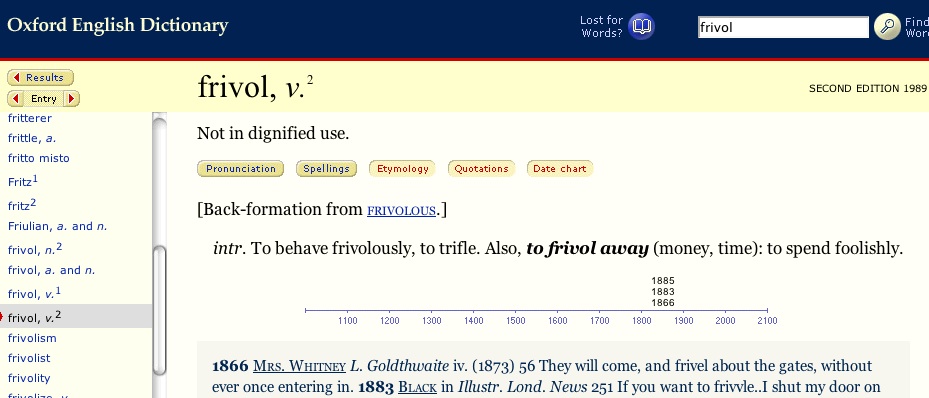

Update: Pursuant to a comment on the crosspost from Ricky, I went to check on frivol- -- I'd forgotten that it had a free use! It's a back-formation, though, so at least it used to be a bound root. Check out the OED's rather severe usage note:

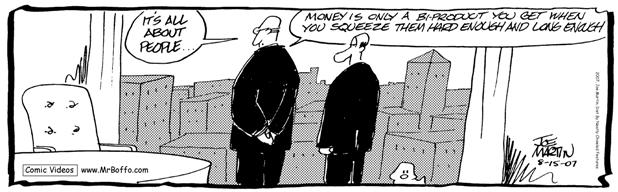

Memetic mutation and traumatic release

Today's Stone Soup deals with a case of linguistic abilities unlocked by trauma: Max has fallen out of a tree on his head, and he suddenly jumps from babytalk to hyper-formal adult sentences:

This reminds me of a story that I heard long ago, about Thomas Babington Macaulay. Robert Herrick and Lindsay Todd Damon, Composition and Rhetoric for Schools, 1905, give this version in a (sample passage titled) "Theme on Macaulay":

Even in his early childhood Macaulay showed evidences of his coming greatness. At the age of four he had learned to read, and at five he had read the entire Bible. As early as this, too, he began to use those long words which are so much in evidence in his writings. Illustrative of this fact is the following anecdote. While he was dining one day with his father and mother at the house of a neighbor the servant upset a cup of coffee on his legs. On his hostess's inquiry as to whether he was hurt, the young Thomas immediately replied: "Madam, the agony is somewhat abated."

The story is presented in a very different way in Randall Jarrell's 1954 novel Pictures from an Institution. Young Derek doesn't speak, but only growls, and his mother consults a specialist, who tells her that

... "talking is simply a matter of maturation," but advised, as a precauation, "a thorough physical check-up." He went on to say that Carlyle's first words, delivered at the age of three, had been what ails wee Jock? -- that Lord Macaulay's first words had not come until he was four; a lady had spilt hot tea on him at a party, and he had said, drawing back a little from her solicitous caress: Thank you, Madam, the agony is somewhat abated.

Dinner has become a party, and coffee has become (more stereotypically British) tea. And the quotation, no longer the rhetorical fruits of precocious Bible-reading, is now the first utterance of a late talker, who needed the stimulus of scalding to unlock his tongue.

Jarrell's version is the one that I heard at some point in my childhood. I recall that this story was brought out by adults in exactly the context described in Jarrell's novel, as a way of offering support and encouragement to parents of late talkers. I don't know whether I heard people repeating something they had read in Jarrell's novel, or whether Jarrell's novel reproduces a piece of pre-existing intellectual culture.

In any case, I doubt that scalding and concussion ever actually increase mental abilities, but there's something intuitively plausible about such stories, perhaps because of the analogy to awakening from sleep.

[Alejandro Satz writes:

I remembered that I had read the story of Carlyle's and Macualay's first words, almost in the exact words that you copy from Jarrell, in Bertrand Russell's book An Outline of Philosophy. I checked it finding the book in Google Books and making a search of "Carlyle"; the stories come up in page 40. I reckon Jarrell might have copied it from there, or else both him and Russell copied from the same source, because the two anecdotes are there and with very similar wording. Russell's book is from 1927.

In fact, the passage has some independent interest:

Certain philosophers who have a prejudice against analysis contend that the sentence comes first and the single word later. In this connection they always allude to the language of the Patagonians, which their opponents, of course, do not know. We are given to understand that a Patagonian can understand you if you say 'I am going to fish in the lake behind the western hill', but that he cannot understand the word 'fish' by itself. (This instance is imaginary, but it represents the sort of thing that is asserted.) Now it may be that Patagonians are peculiar -- in they must be, or they would not choose to live in Patagonia. But certainly infants in civilised countries do not behave in this way, with the exception of Thomas Carlyle and Lord Macaulay. The former never spoke before the age of three, when, hearing his younger brother cry, he said 'What ails wee Jock?' Lord Macaulay 'learned in suffering what he taught in song', for, having spilt a cup of hot tea over himself at a party, he began his career as a talker by saying to his hostess, after a time, 'Thank you, Madam, the agony is abated.' These, however, are facts about biographers, not about the beginnings of speech in infancy. In all children that have been carefully observed, sentences come much later than single words.

The wider context is a theory of meaning based on conditioned reflexes -- I had completely forgotten this aspect of Russell.

Anyhow, I like his observation that "These ... are facts about biographers, not about the beginnings of speech in infancy." And this leaves me wondering about the origin and progress of the biographical tidbit about Macauley's burn. ]

[Jan Freeman writes:

I dimly recall from college days that the "Stone Soup"/Carlyle storyline -- the hero who is mute as a toddler then suddenly acquires eloquence -- is a folktale motif as well as a later urban legend. Beowulf, maybe? (I'm on deadline, and recovering from a computer catastrophe, or I would do further research.)

But I clipped "Stone Soup" for another reason. The first dialogue balloon illustrates a common agreement problem that baffles many of my peeve-conscious correspondents.

"Max is one of those kids who doesn't talk much . . . but has it all in their heads."

Many people want "one" to govern the following verb, instead of "kids" -- and that makes the rest of the sentence difficult ("has it all in their heads"). But "one of those kids who don't talk much . . . but have it all in their heads," though grammatically correct and simpler, sounds wrong to many people. Can't remember if Language Log has covered this, but it drives my readers wild, whichever version they prefer.

See " One of those who" (6/7/2006) and " One of those people that care(s)" (11/21/2006). ]

[Ray Girvan observes that the Vietnamese hero Giong is a good example of the folktale motif of a mute toddler who suddenly acquires eloquence.]

[Jesse Sheidlower writes:

A favorite literary late-speaker is Charles Wallace Murry, the genius hero of Madeleine L'Engle's A Wrinkle in Time. We are told that he was completely silent until the age of four, when he began to speak in complete sentences, with "none of the usual baby preliminaries." (From memory, but I always found that line memorable.) Later he uses some hard word, is challenged on its meaning, and responds by quoting the definition in the Concise Oxford Dictionary (which definition he disparages). This at the age of five.

]

[Douglas Davidson writes:

A Carlyle/Macaulay-type anecdote is also told of Einstein, e.g. Reuben Hirsch et. al., The Mathematical Experience, p. 188 (footnote):

Otto Neugebauer told the writer the following legend about Einstein. It seems that when Einstein was a young boy he was a lake talker and naturally his parents were worried. Finally, one dat at supper, he broke into speech with the words "Die Suppe ist zu heiss." (The soup is too hot.) His parents were greatly relieved, but asked him why he hadn't spoken up to that time. The answer came back: "Bisher war Alles in Ordnung." (Until now everything was in order.)

Allan Wechsler sent in the same anecdote, and adds:

Without a decent research library I can't figure out how reliable the story is, nor who the real source is [...] Perhaps some young intern at Language Log Plaza could be detailed to ascertain the truth of this legend?

I knew there was something missing around here!]

[With respet to the Macaulay quotation "Madam, the agony is somewhat abated", Thomas Thurman writes:

I first encountered this anecdote in a book by the English writer Frank Muir, who added "I think the temptation to spill coffee on such a child must have been quite strong."

]

[8/31/2007 -- it looks like the thread is going to go on for a while:

]

[Kathleen Burt writes:

It may be that words always precede sentences, but the child may practice in secret as it were. My second daughter's first noticed speech was the sentence "Here comes Joe on his motorcycle." And sure enough here he came. On his motorcycle in fact. My daughter was under a year old, and could not stand up unaided. We are pretty sure she didn't know she was overheard, and was practicing speech. In later years we knew her as a child who insisted on learning everything by herself, with as little input from her elders as possible.

Max's newfound eloquence didn't entirely surprise me, and I have heard the other examples before. I have to say that the example involving Carlyle strikes me as better founded, because "What ails wee Jock?" is the sort of household utterance that would be heard by people who were well-positioned to hear the child's first speech. Something said at a dinner party might be widely reported by people who had no real idea how well the child was able to speak, and family comments that it wasn't really the first thing he'd ever said might not be heard by those who were spreading the story.

In some cases, an infant may be treating a phrase in a holistic way. At a time when my oldest son was using only single words, and not all that many of them, he came out with the phrase "what's going on here?" It was in an entirely appropriate context, but I've always assumed that he'd learned this phrase as a unit, glossed as an expression of disapproving amazement. But I admit that "Here comes Joe on his motorcycle" is a less plausible candidate for that sort of interpretation.

Another ]

Posted by Mark Liberman at 07:52 AM

If you're a fan of cute headlines

Here's your daily dose: "Love triangle kidnap pampernaut preps wingnut defence", The Register, 8/29/2007.

But "wingnut" usually has a political dimension that's missing here -- the story makes it clear that Nowak's defense team is contemplating a plea of temporary insanity, not temporary Republicanism. (Though the way things have been going recently...)

Is frequent use bleaching the politics out of the term wingnut in general, or was The Register's editor just seduced by the "kidnap pampernaut"/"wingnut defense" chiasmus? In any case, the wordplay inspired by the other recent national adult-diaper story has been spiritless in comparison.

[hat tip to David Donnell]

[Askash Mehendale thinks it was the Atlantic ocean that did the bleaching:

I would suggest a third explanation: that over on this side of the pond (as I am, and the Reg staff mostly are), 'wingnut' means only one of:

- a particular type of nut (as in nut-and-bolt), with protruding wings that make it easier to turn

- a person with protruding ears (by association with the above)

- an insane or merely strange personIn my experience, the last arrived from AmE (if that's where it came from) without any political connotation.

One piece of evidence for this spin on the word is the Microsoft/Peter Jackson joint venture Wingnut Interactive, located in New Zealand (and thus subject to an even larger dose of salt-water bleaching). Certainly there's no evidence that Jackson has right-wing politics that he feels strongly enough about to put into his games-studio name.

However, I don't see a lot of other evidence of wingnut used simply to mean "insane or strange". ]

[Boyd D. Garrett Sr. writes:

During my tenure in the Navy from the mid-70s through the mid-90s, I worked quite a bit with colleagues from the Air Force. We frequently referred to them as "wingnuts," roughly meaning "those insane or strange people who are often organized into Wings" (a major organizational division used by the US Air Force: see the Wikipedia entry). I seem to recall the term being used generically outside any military reference, but I can't provide any citations, unfortunately.

I don't know when this term came to be popularly applied to "right-wingers," but I don't recall hearing it used that way until this century.

]

[George Amis writes (from Santa Cruz):

There's a famous Santa Cruz surfer called Wingnut (his real name is Robert Weaver). He appeared in a surfing film called Endless Summer II. I'd be surprised if he has much interest in politics. The Wingnut apparently refers to his wild and crazed behavior on and off the waves.

]

"UAT Instructor Creates Cuneiform and Hieroglyphic Translator"

An announcement at Marketwire claims that Joe McCormack, an instructor at the University of Advancing Technology (warning: awful Flash website with unreadable text and high buzzword density), has created a program that translates English into ancient Egyptian, Akkadian, and Sumerian. The story has made it to Slashdot, and the Marketwire story reports that McCormack is "talking with museums and institutions to garner further exposure".

Let's nip this one in the bud, before the BBC picks it up, and before any ill-informed museums or schools start using this thing. It doesn't work. I don't know much Akkadian or Sumerian, but I do have a fair knowledge of Egyptian, enough to test this translator. If you enter single words, it will often return a reasonable result, though in a number of cases the result is not what I would consider the usual word or spelling. The system doesn't seem to have a very large vocabulary. Quite a few of the words I tried were missing, including both ordinary words like "silent" and names of major Egyptian gods. If, however, you enter sentences, the result is invariably gibberish. This system has no knowledge of Egyptian grammar. The word order is all wrong. The verbs are not inflected. For possessed forms of nouns, which are formed with suffixes in Egyptian, some of the affixes are wrong, and in all cases that I tested they are in the wrong position.

This system is not a translator. It is a crude lexical lookup system, basically just a dictionary. It is probably fun to play with if you don't know the languages, but it is way over-hyped, and if used by schools and museums will be terribly misleading to people who would actually like to learn about these ancient languages.

August 29, 2007

Intelligence analysis: football vs. law

I was impressed by a Washington Post article that describes the painstaking labor facing today's college football coaches. The University of Maryland's coach, for example, refers to tapes as his "textbooks." Coaches fill their off-field time analyzing tapes. A new industry of videotaping practice sessions and games has created jobs called "video coordinator" and at least big-time teams are now cooperating with each other by sharing their tapes with opposing coaches. Football tape libraries are springing into existence. This is a far cry from the old days, when teams were forced to have scouts armed with clipboards gather useful intelligence for their upcoming games. But this is Language Log and there has to be a reason why I'm talking about football. So here it is. I see a relationship between between taping naturally occuring physical activity (football) and taping naturally occuring language, which may be even more fleeting and harder to capture for later analysis.

Sociolinguists who study language in its natural context know full well how difficult this task can be. We used to audiotape interviews and conversations with people (calling them 'subjects' sounds demeaning somehow). After we got the sample we wanted, we spent hours and hours doing serious analytical work on them. Every sound, morpheme, word, phrase, clause, pause, and false start were potentially important indicators of information about such things as a speaker's regional background, social status, education, race, gender, age, and attitude. As technology developed, we turned to videotapes because they provided even more information, such as the distance between speakers, non-verbal signals, and other things.

Taking advantage of the same technology, law enforcement began using audiotapes in undercover sting operations in the late seventies and continued to do so for the decades following, finding that this practice provided more convincing evidence of the willingness (sometimes unwillingness) of suspects to commit language crimes. As the technology advanced, these agencies also began to use videotapes. They too found that this was a lot of work. But their main problem was less in gathering intelligence than in analyzing it.

Football coaches have a distinct advantage over law enforcement officers and lawyers. Like linguists, coaches are trained to be experts in their jobs and they are willing to spend night and day analyzing their own and their opponents' skills and strategies. The big difference between analyzing football tapes and analyzing law enforcement tapes is that the police and prosecutors are not trained experts in the very language that the tapes provide them. But linguists are the real experts in this kind of intelligence analysis, explaining why more and more of them are being called upon to analyze the language evidence in criminal and civil cases.

What she should have said

The question: "Recent polls have shown, a fifth of Americans can't locate the U.S. on a world map. Why do you think this is?"

The (famous) answer:

I personally believe

that

U.S. Americans are unable to do so

because uh some uh

people out there in our nation don't *have* maps

and uh I believe that our ed- education like such as in

South Africa and uh the- the Iraq everywhere like such as and

I believe that they should uh

our education over here in the U.S. should help the U.S. or- or- should help South Africa

and should help the Iraq and the Asian countries

so we will be able to build up our future

((for our children))

But what she should have said was:

That sounds like an urban legend to me --I don't believe that my fellow Americans are so ignorant. According to the Final Report of the National Geographic-Roper Public Affairs 2006 Geographic Literacy Study, "Nearly all (94%) young Americans can find the United States on the world map".

The last time I checked, 100% minus 94% was 6%, not 20%. So what's your source for the claim that 20% of us don't know where our country is on the map?

I don't know where the pageant organizers got "one fifth" from. My guess is that they just made it up -- or more charitably, one of the them dimly misremembered a number from one of the periodic hand-wringing "People are so ignorant of X" press releases distributed by the purveyors of X.

Let's note in passing that the National Geographic gave its study the same shocking-ignorance-is-rife spin in its press release, duly picked up by the press, e.g. "Study: Geography Greek to young Americans", CNN.com, 5/4/2006):

The National Geographic-Roper Public Affairs 2006 Geographic Literacy Study paints a dismal picture of the geographic knowledge of the most recent graduates of the U.S. education system.

"Taken together, these results suggest that young people in the United States ... are unprepared for an increasingly global future," said the study's final report.

"Far too many lack even the most basic skills for navigating the international economy or understanding the relationships among people and places that provide critical context for world events."

Needless to say, the 94% number was not featured. In fact, the key paragraph of that news story is the last one:

The release of the 2006 study coincides with the launch of the National Geographic-led campaign called "My Wonderful World." A statement on the program said it was designed to "inspire parents and educators to give their kids the power of global knowledge."

In other words, it's designed to inspire parents and educators to give the National Geographic the power of their dollars.

(I hasten to add that geographical knowledge is a wonderful and important thing, and everyone needs more of it. But let's be clear about what's going on here...)

[Update -- Michael Kwun thinks this might be another example of inability to deal with simple proportions:

I don't know what really happened, but it could be that a question about geographic failings accidentally demonstrated an innumeracy problem.

If 94% can find the US on a map, that could easily be reported or remembered as 95%.

And that would mean 5% can't find the US on a map. Five percent can morph into 1/5 through a simple error in recollection... or because someone doesn't understand how to translate percentages into fractions.

Or you could turn 5% into 1 in 20... which could then similarly turn into 20%, and then 1/5.

]

It's whom

UBI Soft's Sprung for the Nintendo DS ("A Game Where Everyone Scores") is

... a dating simulation designed to challenge your thinking skills. What do you say to that cute stranger you've just met? Do you know what to say to make them laugh and smile? Will you mess up and make them angry at you?

The reviews on amazon suggest why this game has not been a hit:

I did enjoy this game enough to solve it with both a male and a female. It is quite fun to try to use items on different people to see what will happen, like spraying them with mace.

The concept seems kind of cool at first: you want to fall in love with the main character of the opposite sex. The problem is, everything in this game is completely impossible to predict. If you pick the seemingly best responses, you don't necessarily win.

I havent completed the game, But i intend to if i can get over the part where becky has to get conor to ask her out. If you know how to pass that part, PLEASE post the awnsers on here for the game. i cant even get past the part where brett is on a scavenger hunt, and has to get 2 things, 1. Womens underwear and 2. a pic of a dragon tattoo plz help me thanx

Apparently, as an alternative to spraying cute strangers with mace, you can get prescriptive with them:

(As James Thurber explained many years ago, "it is better to use 'whom' when in doubt, and even better to re-word the statement, and leave out all the relative pronouns, except ad, ante, con, in , inter, ob, post, prae, pro, sub, and super.")

It seems to me that Nintendo and Ubi Soft have missed an opportunity here. They should have hired some really interesting writers to create interactive modules for this game. You could select Alice Munro's version, or Dave Barry's -- or let the DS shift randomly among them.

If you want to explore Sprung further, this thread at Something Awful looks promising.

[hat tip to Caitlin Light]

August 28, 2007

Disarming the global road worrier

I thought that Pete Ianace had come up with a clever pun, but he seems to mean it.

I thought that Pete Ianace had come up with a clever pun, but he seems to mean it.

I used to be a global road worrier, myself, but then I realized that I can prepare classes, do research and answer email just as well in an airport in city X as in a hotel conference-room in city Y. In fact, the surroundings are usually less distracting, the network is usually less congested, and the situation is spiritually more fulfilling.

After all, "the way of the Tao is to act without thinking of acting, to taste without discerning any flavour, to consider what is small as great, and a few as many, and to react to injury by kindness." What better way to engage these truths than to be stranded in an airport?

Political semantics quiz

Rahm Emanuel, the sharp-tongued chair of the House Democratic Caucus, said this about our soon-to-be-ex attorney general: "Alberto Gonzales is the first attorney general who thought the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth were three different things".

Translate Emanuel's comment into higher-order predicate calculus. What is the minimum order of predicates that you need to quantify over?

Are these three phrases actually just different names for the same thing? If not, how do you explain the (redundant?) wording of the traditional oath? If the three phrases do name different concepts, give one example of each of the three categories from Gonzales' congressional testimony.

[ Tim Finin, who should be grading the quiz, offered an answer:

Here's my attempt at the first part. I'll leave it to others to others to see if AGAG followed the traditional oath, which I'll assume is something like: "AGAG promises to tell (1) the truth, (2) the whole truth and (3) nothing but the truth."

(1) If AGAG tells P, then P is true.

All(P) tell(AGAG,P) -> P.

(2) If AGAG tells P, then P is true and there is no sentence R that is not implied by P that is true.

All(P) tell(AGAG,P) -> P ^ ~ Exists(R) R ^ ~(P->R)

(3) Same as #1: If AGAG tells P, then P is true.

All(P) tell(AGAG,P) -> P.

I am assuming what I take to be a standard interpretation of what it means to "tell the truth", i.e., to make statements that are true and not to make any statements that are not true. Of course, the standard interpretation probably also involves saying things that you 'know' to be true, but I don't want to go there tonight.

So Tim thinks that the three phrases are only partly redundant, since the first and the third mean the same thing.

That's what I thought, too -- at first. But after a bit more thinking, I decided that it's not so clear. After all, if I promise to eat the pie, the whole pie, and nothing but the pie, all three clauses seem to be independent. ]

[Simon Cauchi brings a different semantic tradition to bear, according to which telling the truth is indeed like eating the pie:

"The truth" means just that. It's not qualified in any way.

"The whole truth" expressly disavows suppressio veri.

"Nothing but the truth" expressly disavows suggestio falsi.

]

[Barbara Partee comments:

Only time for a quick response: I think the best way to see them all as non-redundant (and to make the "whole truth" one fulfillable!) is to think of them all in the context of answering questions.

That limits the domain of potentially relevant propositions -- I'm not taking time to work this out carefully -- we're about to leave for a few days getaway -- but it narrows down the first one so that it's not about everything you say but about giving a true answer to the question. And 'whole truth' doesn't then mean that you have to give an answer that specifies all the true propositions about the whole actual world (which Tim's requires), but just a complete answer rather than a partial answer. And then the 'nothing but' is also no longer redundant, I guess, because it means you don't add on anything false.

Wait, or does it mean that you don't add anything irrelevant? You don't add anything that isn't implied by a complete true answer to the given question? Hmm, nothing irrelevant or just nothing that's both irrelevant and false? (A clever answerer can still make hay with implicatures -- I don't think the rule says anything about not implicating anything false, only about not actually saying anything false.)

]

[Rory Turnbull writes:

After reading your Language Log post on the semantics of "the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth", it struck me that it's really just an oath to obey Gricean conversational maxims.

The truth - maxim of quality

The whole truth - maxim of quantity

Nothing but the truth - maxim of relation

]

Syntax under pressure

According to the Doonesbury site's feature "Say What?" today, Lauren Caitlin Upton, the reigning Miss South Carolina, was recently asked on TV why so many Americans can't find their own country on a map, and her impromptu reply, dutifully transcribed by various sources (though not yet checked aganst the original recording by Language Log staff), was:

I personally believe that U.S. Americans are unable to do so because some people out there in our nation don't have maps, and I believe that our education like such as South Africa and the Iraq everywhere like such as, and I believe that they should... our education over here in the U.S should help the U.S or should help South Africa and should help the Iraq and the Asian countries so we will be able to build up our future.

Those who enjoy laughing at stereotypically pretty young women (yes, Miss Upton does appear to be blonde) for stereotypically lacking intelligence will get a few giggles out of this one. And they will probably not reflect on whether they themselves have ever sounded similarly stupid when speaking spontaneously under pressure and under lights, in response to an unexpected question under circumstances that made them feel they are expected to talk.

There can be no doubt that the young woman in question had no idea what she was going to say, except that she knew she should try to mention maps and name a country or two and sound sort of interested in foreign affairs and education. But I have a feeling I have occasionally blundered around in similar manner myself when faced after a conference presentation with a question I simply had no answer to.

Normally one can just say nothing, or "I have no idea", if one has no idea. But there are some circumstances in which all the attention is on you and you feel you have to provide some talk: being on TV, press conferences, classes where you're the teacher, prime minister's question time, job interviews, parole board hearings, question periods, and so on.

The one syntactic peculiarity (as opposed to the general fluency meltdown) that caught my eye was "the Iraq", which occurred twice. But this is a tricky topic (no wonder so many Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Russian speakers are utterly baffled over when to use the definite article and when not). What Miss Upton was struggling with was the question of whether Iraq is a strong or a weak proper name. Weak proper names need the definite article. Strong ones don't. You may be clear about the difference, but large numbers of people think that Language Log is a weak proper name (needing the), as we see from our mail every day. (It is not true. Language Log is a strong proper name: we do not prefix it with the definite article.)

The matter is not trivial or straightforward. As noted in The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language, pp. 517ff, there are a number of countries that have two different ways of being referred to, strong and weak, the weak forms being a bit more common in Britain and tending to be replaced by the strong forms:

| strong | weak | |

| (no article) | (with article) | |

| Argentina | the Argentine | |

| Ukraine | the Ukraine | |

| Yemen | the Yemen | |

| Lebanon | the Lebanon | |

| Holland | the Netherlands |

There are some generalizations, but also many exceptions. Cities, boroughs, and regions are usually strong (like Amsterdam or New York or North Africa or Antarctica) but a few are weak (like the Hague or the Bronx or the Maghreb or the Antarctic). And remarkably, to a rough approximation at least, numerical freeway names are weak proper names in Southern California ("Get on the 55") but strong proper names in Northern California ("Take 17 South").

Don't laugh too hard at poor Miss Upton until you've successfully answered a few geography quiz questions under TV lights, that's what I'm saying.

Addendum: For those interested in checking the text, this blog post has a link to the video (it's on YouTube of course), and offers the following slightly different transcript (slightly more disfluent; and it agrees on *the Iraq):

I personally believe that U.S. Americans are unable to do so because, uhmmm, some people out there in our nation don't have maps and uh, I believe that our, I, education like such as uh, South Africa, and uh, the Iraq, everywhere like such as, and I believe that they should, uhhh, our education over here in the US should help the US, uh, should help South Africa, it should help the Iraq and the Asian countries so we will be able to build up our future, for us.

Reuters says guilty of elliptical headlines

When the news hit the wires last Friday that Atlanta Falcons quarterback Michael Vick was pleading guilty to charges involving illegal dogfighting, the Reuters headline read:

Which of these three possible readings would you suppose is the one that the headline writer intended?

a) The verb say(s) functions as a more informal substitute for plead(s), since plead can be followed by the adjectival complement guilty to mean 'enter a guilty plea.'

b) The verb say(s) is quotative, with guilty as a direct quotation complement (or at least a partial one). This draws on our cultural understanding that saying "guilty" in court proceedings is elliptical for the declarative speech act "I am guilty" (i.e., "I am entering a guilty plea"). Such a reading would imply that the headline writer neglected to include quotation marks around the word guilty. (Compare the recent New York Post headline, "Cousin Vinny wiseguy says 'guilty' to go free.")

c) The verb say(s) is reportative, with guilty as an indirect quotation complement (or at least a partial one). In this type of ellipsis, "Vick says guilty" is journalistic shorthand not for "Vick says 'I am guilty'" but for "Vick says (that) he is guilty."

Attentive Language Log readers will recognize that the third reading is the most plausible one, given the source of the headline. As Arnold Zwicky explained a month ago, Reuters headlines are very often of the form "X say(s) C," where C is a complement clause missing a subject.

The headline that set the Language Log water cooler buzzing last month was: "Taliban say kill Korean hostage, set new deadline" (July 25). To help illuminate this construction, Barbara Partee and I dug up a large number of Reuters headlines taking the form "X say(s) find Y," as in "Scientists say find gene for child cancer syndrome" or "Statoil says found oil northwest of Shetlands." In such cases, the complement clause for say(s) is a finite VP with the subject omitted. If we were to restore the missing subject in each of these headlines, it would be a third-person pronoun coreferring with the antecedent X: "Scientists say (that) they find gene," "Statoil says (that) it found oil," and so forth.

Now it turns out that the predicates of these subjectless clauses don't necessarily have to take the form of a finite VP like "kill Korean hostage" or "find gene." Reuters headline writers are routinely writing headlines of the form Subject say(s) Predicative with the intended interpretation of Subject say(s) (that) Subject is/are Predicative. In ordinary English, such reported-speech constructions look like the following, with a predicate consisting of a finite form of be plus AP, PP, participial VP, or NP:

1. Joan says (that) she is enthusiastic about the team. (be + AP)

2. Joan says (that) she is on the board of directors. (be + PP)

3. Joan says (that) she is getting fed up with his shenanigans. (be + VP with V-ing head = Present Participle)

4. Joan says (that) she is protected against bankruptcy. (be + VP with V-ed/-en head = Passive Participle)

5. Joan says (that) she is a finalist for the big award. (be + NP)

In the peculiar register of Reuters headlinese, we would lose the subject of each complement clause (she) along with the copular verb be:

1a. Joan says enthusiastic about the team.

2a. Joan says on the board of directors.

3a. Joan says getting fed up with his shenanigans.

4a. Joan says protected against bankruptcy.

5a. Joan says a finalist for the big award.

Copula deletion is nothing unusual in elliptical headlinese, as in these recent examples from the Associated Press: "Gonzales a lesson in cronyism," "Wilson in good condition, hospital says," and "Idaho senator arrested in airport." To my eyes and ears, it's more than a little weird to lose the copula and the implied subject of the complement clause (even if the subject is just a pronominal placeholder). But that's just what the Reuters headline writers do on a regular basis. I went through the Reuters archive and collected five examples of each predicate type numbered above, beginning with the adjectival type exemplified by the Vick headline. Most of the types are easily adduced by looking at headlines for the month of August.

- AP

- Malaysia says well able to handle external shocks (Aug. 23)

- Automakers say open to sharing parts (Aug. 23)

- Premier Foods says set to cut 430 jobs in Britain (Aug. 22)

- UK says confident will be cleared of foot and mouth (Aug. 21)

- US parents say wary after China product recall (Aug. 15)

- PP

- Lufthansa says on course for 2007 profit boost (Aug. 23)

- Quest Software says not in compliance with Nasdaq (Aug. 21)

- Hamilton says not at war with team mate Alonso (Aug. 9)

- Al-Rajhi says on prowl for foreign expansion (Aug. 6)

- National Health says still in talks with "third parties" (Aug. 6)

- Pass Part

- French police say beaten in Guinea over immigrants (Aug. 23)

- Thai PM says not worried about large "No" vote (Aug. 22)

- US navy chief says reassured during China visit (Aug. 21)

- Alitalia says contacted by group of investors (Aug. 21)

- Casino operators say insulated from credit crisis (Aug. 16)

- Pres Part

- Bear rivals say courting prime broker clients (Aug. 24)

- Foot Locker says not providing EPS forecast (Aug. 23)

- Pride says working with Pemex to assess rigs in Dean (Aug. 22)

- Formosa Plastics says mulling China stainless mill (Aug. 22)

- Albertson's says recalling some green beans (Aug. 3)

- NP (These are the hardest to search for in the Reuters archive, so I had to dip into the Factiva database for older examples. I've also given the first sentence of each article so that the meaning of the headline is made clear.)

- Areva says a National Grid preferred partner (Oct. 24, 2006)

Areva, the world's biggest maker of nuclear reactors, said on Tuesday it had been selected with its alliance members as one of six preferred partners by Britain's National Grid for contracts worth over 4 billion euros. - United (UU.L) says a preferred pick for water deal (Jan. 31, 2003)

UK water and electricity provider United Utilities Plc said on Friday it had been named as a preferred bidder for a contract with state-owned Scottish Water for a 1.8 billion pound ($3 billion) investment scheme. - Edison says a long-term holder of Contact (Jan. 29, 2001)

Edison Mission remains a long-term investor in New Zealand's Contact Energy, Edison's nominee on the board, Bob Edgell, said on Tuesday. - National Foods says a buyer, not target (Nov. 14, 2000)

Australian dairy group National Foods Ltd said on Wednesday it was a buyer rather than a takeover target in the domestic industry's rationalisation. - Emulex says a victim of hoax press release (Aug. 25, 2000)

Emulex Corp. on Friday became the victim of one of the most far-reaching hoaxes to hit the U.S. stock market, causing the data networking equipment maker's stock to plummet more than 50 percent.

- Areva says a National Grid preferred partner (Oct. 24, 2006)

There's one additional type of predicate specific to headlinese: the infinitival "to VP," understood as a simple future or as shorthand for 'be ready/set/prepared to VP.' This construction is routinely used when reporting on corporations or other institutions that make projections for the future (earnings forecasts and the like). Not surprisingly, subjectless complements of this type abound in the Reuters archive, though whether these also involve copula deletion depends on how you interpret the tricky headline infinitival:

When I ran these Reuterisms past the keen eye of Arnold Zwicky, he wondered if it was possible for Reuters headlines to omit the subject in the complement clause for say without losing the copula. As Arnold notes, copula deletion is "customary in headlines, in fact, except when the head writer needs material to fill a line, but it isn't obligatory." As it turns out, copula deletion isn't obligatory even in the special Reuters case of Subject say(s) Predicative. Here are recent examples of the five predicate types with the copula intact but the subject missing:

- AP: ABN AMRO reports Q2, says is neutral on bids (July 30)

- PP: Abcam says is in talks with potential offerors (July 27)

- Pass Part: Arab-led Darfur rebels say are victimized too (Aug. 20)

- Pres Part: CIT says is looking at student loan stock deals (Apr. 5)

- NP: Hardliner Nikolic says is 'no danger to Serbia' (May 8)

Since the headline writers of newswires like Reuters are not concerned with the formal limitations of newspaper column widths, I doubt that the choice to keep or lose the copula is a matter of "filling a line." (It's generally not a concern for the online media outlets that reproduce the headlines, either.) Rather, it appears to be more of a stylistic choice, up to the judgment of a given headline writer or editor. And the Reuters practice of deleting the subject of the complement clause for say doesn't appear to be irrevocable "house style" either, since it's possible to find such headlines as "Bush, Karzai say they are aligned against Taliban" (Aug. 6) or "Freed Indian doctor says he is victim of conspiracy" (July 30). Still, the Subject say(s) Predicative flavor of ellipticality seems peculiar to the world of Reuterese. I wonder if it's enshrined in their style guides or if new staffers simply pick up this mannerism from their older colleagues.

All of this reminds me of another quirk of journalistic style: Time Magazine's much-maligned inverted syntax, famously ridiculed in 1936 by The New Yorker's Wolcott Gibbs: "Backward ran sentences until reeled the mind... Where it all will end, knows God!" Well, it did all end, just a few months ago. According to the New York Times, "the last remnants of Time’s signature syntax" were finally banished by editorial fiat in March, just 84 years after Henry Luce founded the magazine. Reuters, there's hope for you yet!

August 27, 2007

Prepositional cannibalism at Google

A nice sighting by Tim McKenzie:

I have recently started getting a trickle of spam to my previously safe gmail address. Google helpfully (and accurately) filters the spam for me, but I often check, just to make sure they got it right. Anyway, I got one today that Google apparently thought was a phishing scam, so they warned me "This message may not be from whom it claims to be. Beware of following any links in it or of providing the sender with any personal information." [emphasis added]

Fowler named this phenomenon "cannibalism" ("That words should devour their own kind is a sad fact"), as explained here.

As Tim pointed out, the impulse to omit the second preposition may be connected with the anxiety about prepositions in relative clauses that I discussed recently.

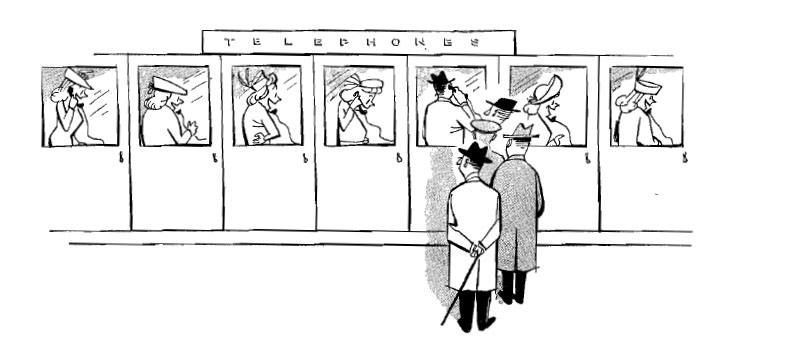

[Update -- Sridhar Ramesh contributed a link to this cartoon, with prepositional cannibalism at the bottom of the second panel:

]

Intimate IM

Zits continues to explore the effects of technology on human communication:

Somewhere, there's probably a clay tablet that makes a similar observation about the effects of cuneiform.

Spreading the brain-sex gospel

This letter from Charles Raymond arrived yesterday. I've posted it in its entirety, with his permission. He mentions some earlier Language Log posts on on Brizendine, Sax and Gurian: a list of links is here.

I am a teacher in an independent school near San Francisco, and an occasional reader of the Language Log. I want to draw your attention to the rapid spread of workshops and talks pushing the "sex-difference" gospel about brain development in the private school world.

I completely understand your effort to counter Brizendine, since the public impact of her bestseller is substantial. I noticed your discussions of Sax and Gurian, but I am very curious if you or anyone you know has followed JoAnn Deak, author of Girls Will Be Girls (her next title, according to her website, will be The Brain Matters). Her writing is in the "expert-advice" genre, rather than the pernicious popular-pseudo-science mode of Brizendine. Deak, however, has built a wide following on the speaker circuit for educators, and she spreads virtually the same line, and drapes herself with the same "backed-up-by-the-latest-science" mantle. She spoke for three hours at our opening faculty meeting, and the presentation was impressive.

Her connections run deep with the schools for girls, for whom she advocates on the basis that biologically determined brain differences are the bedrock reason why many girls need unisex educational settings (completely in line with Sax, the difference being that she has a much larger existing "market" for her services). But she has built her "educational advisor" credentials much more widely than that: she speaks at conferences attended by heads of schools, and apparently receives many invitations to speak at individual schools.

I won't go into the detail -- you are familiar with the pattern -- but I will say that I laughed out loud when I read your description of Deena Skolnick's study ("Distracted by the brain", 6/6/2007). Deak's presentation could be exhibit A for that phenomenon. She was very entertaining, but "neuro-speak" was the hammer in her hand. So much of what she had to say was good and true when it came to practical advice, but the assumed authority of her voice was explicitly her willingness to absorb and accept the NewTrue science, and then to digest and translate that for us as the new gospel of pedagogical practice. Her acceptance of the science ("undeniable facts") was, by the way, really posed as a very "manly" exercise, if I may say so, in putting aside what she would "rather" have believed about men and women. In order to be true to our kids, we need to be "hard-boiled" about our biology. That rhetorical approach was so incredibly disarming and yet also intellectually intimidating at the same time.

I will attach some links on this subject below, but please do let me know of any other communication you might have had about her. I am trying to put together some materials to counter this sort of thing in my professional community, but I'm afraid it's like fighting the tide. The very day after her talk, an email went around notifying us all about a talk by Brizendine at a local bookstore. The appetites were whetted, so why not go to the source?

I should add that I support the modest growth of unisex education, but not because I believe that the biologically determined differences in cognitive development or learning styles are so salient that we need to redesign our institutions and practices around them. There are sufficient cultural and psychological arguments for different school settings. It's too bad some people feel the need to appeal to false or exaggerated biological determinism, and in a way that I believe may ultimately harm the cause of gender equity.

Some links:

Deak's own website makes it clear that she is making the rounds of independent schools.

The National Coalition of Girls' Schools endorses a similar view in a booklet that prominently cites Deak.

And individual girls' schools feature her name in various ways.

Here is Brizendine herself giving a talk quite similar to Deak's at the 2006 NAPSG meeting (the National Association of Principals of Schools for Girls).

This Canadian article (Anne Marie Owens, "Boys' Brains are From Mars", National Post, 5/10/2003) pairs Deak with Sax, and it gives an excellent description of what her rap is like.

[Guest post by Charles Raymond]

[Comment by Mark Liberman -- I found one passage from that National Post article especially striking:

The brain maps are intriguing, but what is more compelling is the sea change that must have taken place to allow these experts to show such slides in benign cookie-cutter conference rooms, pointing out the differences with clinical detachment, without any hint of confrontation or controversy. Doesn't talk of brain differences conjure up images of Canada's own Philippe Rushton and his racial brain delineations? Substitute blacks for boys in these talks and surely these speakers would have been drummed out of such a respectable gathering.

But there is no hint of quackery here. Here's an Ohio feminist with A-list credentials, a female psychologist specializing in girls' empowerment, and she's using the gendered brain maps. Here's a Maryland pediatrician, whose articles have been published in leading academic journals and who is a known champion of advancing boys in school, and he is using the gendered brain maps, too.

These were the ideas that thousands of educators from North America's most elite private schools were talking about by the end of last month's conference of the National Association of Independent Schools: What should we make of the science-based differences between boys' and girls' brains? What are the practical implications for educating boys and educating girls? Do traditional single-sex schools need to reinvent themselves to take advantage of this new knowledge? Can co-ed schools continue to make the case for mixed-sex programming in the face of this scientific evidence?

This explicitly makes the connection to old-fashioned racist anthropology and physiology, and to the recent work on sociobiology of racial differences by Rushton and others. That work has been extremely controversial, and has made relatively little headway in the culture at large, as far as I can see. In particular, it's unimaginable that today's American educational elite would enthusiastically host a set of speakers promoting the view that biologically-determined differences between the races, in abilities and interests and learning style and even perceptual sensitivity, are so great that racially-segregated education is the only way to treat each group as it needs to be treated. "Scientific" support for this conclusion would be minutely examined and criticized, and independent of the science, the conclusion would be resisted on ethical and political grounds, and its proponents would be ignored if not shunned.

The amazing thing is how far the brain-sex movement has gotten while raising hardly any controversy at all, despite its generally shoddy, misinterpreted or even fabricated scientific foundations, and its affinities with 19th-century gender stereotypes. (If you're not clear about this, read the links here.) I believe that this is because the brain-sex movement has learned to make its pitch in ways that appeal to feminist prejudices as well as patriarchal ones.]

August 26, 2007

In awe of bologna and doritos

Eric Gorski, "Hispanic congregations adding English services to the mix", AP, 8/25/2007:

On Sundays at La Casa del Carpintero, or the Carpenter’s House, they’ve raised twin yellow banners for churchgoers that read “Welcome” and “Bienvenidos.”

As a complement to the regular 11:30 a.m. Spanish service at the independent Pentecostal church, where they’ve worshipped Papi for years, there’s now a 9:30 a.m. English one where the faithful praise God the Father.

While churches from every imaginable tradition have been adding Spanish services to meet the needs of new immigrants, an increasing number of Hispanic ethnic congregations are going the other way – starting English services.

It’s an effort to meet the demands of second- and third-generation Hispanics, keep families together and reach non-Latinos.

As Geoff Nunberg wrote, in an exchange about Samuel Huntington's Foreign Policy article "The Hispanic Challenge" ("Nativism clings to life at 100 or 101", 6/24/2004):

English is too useful and important to imagine that any immigrant group would be willing to turn its back on it in order to maintain a marginal, ghettoized existence.

Gorski's article makes this point explicitly:

... as the children of immigrants grow up, churches are recognizing that it’s either bolster Spanish with English or give up on the future.

and supports it with examples:

Walter Rubio was born and raised in Guatemala and moved to the United States when he was 12, in awe of bologna and Doritos. Now raising his own family, Rubio attends English services at the Carpenter’s House.

“It’s simple,” said the 35-year-old construction worker. “My son and my daughter, they lean more toward English. If they understand it better, they get a better blessing.”

One thing that seems a bit different from other immigrant communities whose language patterns over the generations I've observed:

Some second- and third-generation Latinos prefer Spanish as their language of worship. When a group of young adults lingered after the Spanish service at the Carpenter’s House, their small talk was in English, not Spanish.

“We grew up going to Spanish services,” said Abdiel Quiles, 28. “It just feels like home.”

[Karen Davis writes:

Might a preference for Spanish as "language of worship" be similar to the longing among some Catholics for Latin masses: a combination of "you're not supposed to understand" and "this is the way it was done when I was a child"? Old Church Slavonic isn't even a form of Russian, yet it's clung to in the Russian Orthodox Church out of tradition.

I had a similar thought. But apparently these people do understand the Spanish services, though they prefer English for their own use. A traditionalist impulse must be part of their motivation, though, as oddly as that seems to sit with the immediacy of pentecostal culture.]

August 25, 2007

Another year of taboo avoidance

It's been almost a year since I assembled an omnibus posting (10/9/06) on taboo avoidance, and the mail has been piling up alarmingly. And now that I've posted briefly on taboo avoidance and plain speaking in the New York Times, it's time to look at the rest of the media, blogs, and the like.

It's dangerous to try to discern general trends in these things, but my impression is that while we might be living in "the Golden Age of taboo avoidance" (as Ben Zimmer has put it to me), we're also seeing some publications guardedly moving towards somewhat greater openness. The result is, of course, confusion and inconsistency. And, in the case of automatic asterisking/bleeping programs, downright absurdity.

Here's a sampling of things that came to me over the past year that haven't been blogged on here. It doesn't pretend to be a complete survey of taboo avoidance (or use) during the year; it merely illustrates a variety of approaches to the problem. (The examples are grouped into rough categories for exposition; no serious analysis is intended by this categorization.)

At this point, after two years on the Taboo Desk at LLP, I would like to take a vacation from tracking taboo avoidance, so that I can attend to some other topics.

1. Approaches to use/avoidance.

Some publications generally go for avoidance. Some, like the Guardian, the New Yorker, and the Economist are on record as using words like cunt and fuck where they are newsworthy (almost always in quotations). So you get the Economist, back on 2.28/02, in reporting a minor transport-ministry scandal, publishing the revelatory quote:

Lane Greene, who relayed this to me on 7/4/06, noted that the Guardian used cunt considerably more often than one might have expected, sometimes in the writer's own voice, as in this column by Peter Tatchell:

2. Circumlocution, paraphrase, and allusion.

The Wall Street Journal (like the New York Times) generally avoids asterisks and the like, in favor of work-arounds, sometimes elaborate and coy ones, as in this article (of 8/18/06) about the movie Snakes on a Plane:

(Thanks to Jake Seliger. More Snakes on a Plane material from Ben Zimmer here.)

Even more tortured is Leah Garchik's

from her San Francisco Chronicle column of 10/17/06 (pointer from Ned Deily). Figuring this one out is a lot like solving a crossword puzzle -- and it doesn't really work in British English.

Indirect allusion can get too indirect. Here's Gawker's complaint (passed on by Matthew Hutson on 10/10/06) about advice from a Washington Post editor asking that writers on the paper find ways to avoid "the N-word", which the editor found "almost cutesy", recommending instead something like "a well-known racial epithet":

(Compare the Times's reporting in the Isaiah Washington affair, where the offending expression -- faggot -- was alluded to as "the remark" and "the slur".)

Equally indirect is the avoidance of jackass on Fox and Friends, as reported by Jon Lighter on ADS-L 8/8/07:

In his 10/18/06 "On Language" column in the Chicago Tribune, Nathan Bierma found himself trying to explain IM chat slang without crossing over the paper's language lines. It turned out that the people he interviewed didn't always get the message:

WTH: About half identified this as "what the [heck]?" though several said they prefer "WTF," ending with a different four-letter word.

Jane Acheson wrote on 10/24/06 to comment on the "hilariously circumspect" approach the Boston Globe takes to dubious vocabulary, citing sport stories with

The Yankees don't [inhale excessively].

in them (the second of which took her some time to interpret). I noted that you get rather a lot of hits for {"don't give a [care]"} and {"don't [inhale excessively]"}.

Even more obscure allusion: Jon Lighter reported on ADS-L 11/1/06 that Fox and Friends had just rebuked Barbra Streisand for using "the firetruck word" in public. Jon noted that Google has cites back to 1999. The expression goes back to the Turtle Club question, "What word begins with the letter F and ends with CK?"

Also on ADS-L, Barry Popik (11/9/06) quoted a 1960 Dallas Morning News article about a Texas stew known variously as "son-of-a-blankety-blank stew", "S.O.B. stew", and "Gentleman-from Odessa" or "Gent-from-Odessa stew". The writer, Frank X. Tolbert, explained that the first two of these names used "an unfriendly term in which it

is implied that the man receiving the insult has canine ancestry on the distaff side", and cited an informant explaining that the last two derived from the reputation of the town of Odessa:

3. Euphemisms and technical vocabulary.

Note Bierma's report of hell as "[heck]", above.

In a startling development, effing (originally a kind of euphemistic abbreviation) is now regarded in some quarters as intemperate language. From a 10/26/06 House of Commons debate (pointer from Dery Earnshaw)

Mr. Speaker: Order. Will the hon. Gentleman withdraw that remark? We must have temperate language in this House. I do not care what is said outside.

Mr. Osborne: I of course unreservedly withdraw the quote from the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions.

Assorted inventive euphemisms of the freakin' etc. type:

This is fargin war! (Scot LaFaive, ADS-L 2/24/07, from the movie Johnny Dangerously)

Technical terminology functions as a substitute in an AP story of 12/13/06 that Eric Jusino pointed me to in the Central Utah Daily Herald

... During the dispute, [Dan] Ryder said [John] Streamas, an assistant professor of comparative ethnic studies, called him a "white (solid waste)-bag."

College Republicans demanded that Streamas be fired. University President V. Lane Rawlins said Streamas would be reprimanded, but not fired.

The report also notes that the Pope is Catholic and bears defecate in the woods.

Then in February came the grerat hoohaa episode, in which this nursery word (or one of many variants: hoo-ha, hoo-hoo, ha-ha, etc.) is used to refer to the vagina. The appearance of "The Hoohaa Monologues" on the marquee of a Florida theater was noted in the NYT :

By LAWRENCE VAN GELDER

Published: February 12, 2007

Under ordinary circumstances, the opening of "The Hoohaa Monologues" on Thursday at the Atlantic Theaters in Atlantic Beach, Fla., near Jacksonville, would not attract much attention. But "The Hoohaa Monologues" by any other name is Eve Ensler's Obie Award-winning, internationally performed play, "The Vagina Monologues."

Last week, after a complaint from a passing driver who became upset because her niece had seen "vagina" on the theater marquee, Bryce Pfanenstiel of the Atlantic said, "We decided we would just use child slang for it," News4Jax.com reported. Down came "The Vagina Monologues." Up went "The Hoohaa Monologues."

But two days later, on Thursday, in response to a demand from the organizers of the production, the original title was restored. The organizers are a group of Florida Coastal School of Law students who insisted that the original title be displayed because they had rights to the play only if they refused any censorship.

"Vagina is the essence of a woman," said an organizer, Elissa Saavedra, "and if you're going to suppress the name, then you're suppressing us as women." All proceeds are to go to charity.

Ben Zimmer was the first to post this on ADS-L, and then other posters reported occurrences of one or another variant on the TV show Ellen; in the movie Boys on the Side; in the Pussycat Dolls' song "Beep"; on South Park; on Grey's Anatomy; and from their own childhoods. Eventually, people became to report other, non-vaginal, uses: the MAD Magazine interjection (of astonishment or triumph) hoo-hah, and the noun meaning 'fuss, to-do', in particular.

4. "[expletive]" and related locutions.

Beep seems to be in fashion these days. Susan Harrelson wrote me on 10/21/06 to report a competition between asterisking and (automatic) beep:

F**king = F**king

I know I was.

But bleep lives on, as in this Variety story of 10/26/06 (passed on by Victor Steinbok) about NBC vs. the Dixie Chicks:

And then there's the audio bleep, turning up in extraordinary places. Here's a report from the Telegraph of 1/27/07:

By Catherine Elsworth in Los Angeles

Last Updated: 2:05am GMT 27/01/2007

An over-zealous censor bleeped out all references to God when editing an in-flight version of the Oscar-nominated film The Queen.

The operator had been told to remove all profanities when preparing a version for several commercial airlines.

When one of the characters addresses the Queen, played by Helen Mirren, passengers aboard certain Delta and Air New Zealand flights heard: "(Bleep) bless you, ma'am" rather than "God".

Jeff Klein, president of Jaguar Distribution, which supplied the airlines, said the removal of God in seven instances was a mistake by an employee who had taken his instructions too literally. The films have been replaced with unedited copies.

(From Ben Zimmer; longer story here. Australian version of the story reported by Matthew Duggan.).

Automated BLEEP insertion (see the discussion of automated asterisking below) has reached new depths. As Ben Zimmer posted to the ADS-L on 8/11/07:

Earlier today there was a post about similar censorship on FoxSports.com, where "BLEEP" is inserted in place of offending words: (link)

Referencing censored bits here: (link)

"The San Francisco Giants trade pitchers Joe Nathan, Francisco Liriano, and BLEEP Bonser to Twins for A.J. Pierzynski." [censoring "Boof" Bonser]

"They were tradinBLEEP oung player who had put up some nice numbers, but wasn't projected to be a star..." [censoring the letters "g a y" in "tradinG A Young player"]

At the same time, we recognize that not everyone out there loves a potty mouth. So if there's an obvious bad word on a blog, story comment, or message board post, we'll try to censor it.

Feeling brave, mature, and adult-ish? Or just want to get in touch with your inner sailor? You can choose to have FOX Sports do nothing, and leave all those R-rated words alone. If you do, you may see some coarse language from time to time in the community. Don't say we didn't warn you!

*Would you like FOXSports.com to automatically censor content you view?*

Below this are two buttons. I clicked "No, don't censor" and now get the unbleeped pages.

Leaving aside the inane rules for censored strings, which are far from catching only "obvious bad words", even if you believe in such a thing, there are two remarkable things about this:

- They unapologetically call it "censorship"

- They offer "censorship" as a customer service feature

An extreme version of the "[expletive]" strategy is just to use empty square brackets, as in these excerpts from the redacted transcript of a taped conversation between Bob Woodward and Richard Armitage, in evidence at the Scooter Libby trial:

ARMITAGE: [ ] Scowcroft is looking into

the yellowcake thing.