March 31, 2004

Convenience for the wealthy, virtue for the poor

Warning: this is a rant. I don't do it very often, but after editing a grant proposal for a few hours this morning, I felt like indulging in one. So bear with me, or move along to the next post. (Now that I think of it, I did indulge in a similar rant just ten days ago. Well, you've been warned...)

I was pleased to find, via Nephelokokkygia, this page by Nick Nicholas on Greek Unicode issues. In particular, he gives an excellent account, in a section entitled "Gaps in the System," of a serious and stubborn problem for applying Unicode to many of the world's languages. He sketches the consortium's philosophy of cross-linguistic generative typography, showing in detail how it applies to classical Greek, and explaining why certain specific combinations of characters and diacritics still don't (usually) work.

Given the choice between the difficult logic of generative typography and the convenient confusion of presentation forms, the Unicode consortium has consistently chosen to provide convenient if confusing code points for the economically powerful languages, but to refuse them systematically to weak ones. As a result, software providers have had little or no incentive to solve the difficult problems of complex rendering.

This reminds me of what Churchill said to Chamberlain after Munich: "You were given the choice between war and dishonor. You chose dishonor and you will have war." The problems of reliable searching, sorting and text analysis in Unicode remain very difficult, in all the ways that generative typography and cross-script equivalences are designed to avoid -- due to the many alternative precomposed characters (adopted for the convenient treatment of major European and some other scripts), and the spotty equivalencing of similar characters across languages and scripts (adopted for the same reason). At the same time, it's still difficult or impossible to encode many perfectly respectable languages in Unicode in a reliable and portable way -- due to the lack of complex rendering capabilities in most software, and the consortium's blanket refusal to accept pre-composed or other "extra" code points for cloutless cultures. I'm most familiar with the problems of Yoruba, where the issue is the combination of accents and underdots on various Latin letters, and of course IPA, where there are many diacritical issues, but Nicholas' discussion explains why similar problems afflict Serbian (because of letters that are equivalent to Russian cyrillic in plain but not italic forms) and Classical Greek (because of diacritic combinations again).

I'm in favor of Unicode -- to quote Churchill again, it's the worst system around "except all those other forms that have been tried from time to time." However, I think we have to recognize that the consortium's cynical position on character composition -- convenience for the wealthy, virtue for the poor -- has been very destructive to the development of digital culture in many languages.

There is a general issue here, about solving large-ish finite problems by "figuring it out" or by "looking it up." While in general I appreciate the elegance of "figure it out" approaches, my prejudice is always to start by asking how difficult the "look it up" approach would really be, especially with a bit of sensible figuring around the edges. My reasoning is that "looking it up" requires a finite amount of straightforward work, no piece of which really interacts with any other piece, while "figuring it out" suffers from all the classical difficulties of software development, in which an apparently logical move in one place may have unexpectedly disastrous consequences in a number of other places of arbitrary obscurity.

I first argued with Ken Whistler about this in 1991 at the Santa Cruz LSA linguistic institute. At the time, he asserted (as I recall the discussion) that software for complex rendering was already in progress and would be standard "within a few years". It's now almost 13 years later, and I'm not sure whether the goal is really in sight or not -- perhaps by the next time the periodical cicadas come around in 2117, the problems will have been solved. Meanwhile, memory and mass storage have gotten so much cheaper that in most applications, the storage requirements for text strings are of no consequence; and processors have gotten fast and cheap enough that sophisticated compression and decompression are routinely done in real time for storage and retrieval. So the (resource-based) arguments against (mostly) solving diacritic combination and language specificity by "look it up" methods have largely evaporated, as far as I can see, while the "figure it out" approach has still not actually succeeding in figuring things out in a general or portable way.

There are still arguments for full decomposition and generative typography based on the complexities of cross-alphabet mapping, searching problems, etc. But software systems are stuck with a complex, irrational and accidental subset of these problems anyhow, because the current system is far from being based on full decomposition.

In sum, I'm convinced that the Unicode designers blew it, way back when, by insisting on maximizing generative typography except when muscled by an economically important country. Either of the two extremes would probably have converged on an overall solution more quickly. But it's far too late to change now. So what are the prospects for eventually "figuring it out" for the large fraction of the world's orthographies whose cultures have not had enough clout to persuade the Unicoders to implement a "look it up" solution for them? As far as I can tell, Microsoft has done a better job of implementing complex rendering in its products than any of the other commercial players, though the results are still incomplete. And there is some hope that open-source projects such as Pango will allow programmers to intervene directly to solve the problems, at least partially, for the languages and orthographies that they care about. But this is a story that is far from over.

Bluffhead

In the April 2004 Scientific American, Dennis Shasha's Puzzling Adventures column discusses the game of Bluffhead. See this post for links to other entertaining discussions of dynamic and epistemic logic.

A natural boost to the immune system

Here is a medical footnote to Rosanne's researches on booger anaphora.

I feel the need to quote Dave Barry again:

Isn't modern technology amazing? A hundred years ago, if you had told people that some day there would be a giant network of incredibly sophisticated ''thinking machines'' that would allow virtually anybody, virtually anywhere on Earth, to hear a herring cut the cheese, they would have beaten you to death with sticks.

Just substitute "to read a Pakistani newspaper report about an Austrian doctor's speculation that eating snot is good for you" -- or some other amazing example of internet information transmission -- for the phrase in red. The original Ananova report is here, but the Pakistani version has a higher stick factor, in my view.

Chatnannies debunked

More bad science reporting, well exposed at waxy.org and Ray Girvan's blog. The over-credulous media this time included New Scientist, BBC News (again!), and Reuters, among others.

Postcard from Peking

Er, Beijing. Um, Peiping. Anyhow 北京.

Some people get to go to Las Vegas for business trips. Others of us (in this case me, Richard Sproat, and Chilin Shih) look elsewhere for our linguistic insights, specifically the Northern Capital of the Central Flowery Mountain. Which, now that I think about it, was also built by people with a lot of money and power at ridiculous expense in a location with really awful weather near a desert. Although the weather just now, thank you for asking, is really quite lovely, spring having arrived, all plum blossoms and willow buds and other Asian cliches.

I can tell you that the variety of food is much better now in Beijing than in my student days (my vague memories of that period seem to involve a lot of watermelon. Watermelon, cabbage, gruel, dumplings. And watermelon. And did I mention the gruel? Not to imply that I'm not fond of gruel, I am, very much, but in those days it was the really boring kind of gruel, not, say, the nice Hong Kong kind with the dried scallops and pig parts.) Anyhow, this isn't watermelon season, but I did get my fill of dumplings, which were quite excellent, I can especially recommend the fennel dumplings (hui xiang jiao zi 茴香饺子). In the last five years or so, it seems, Sichuan food has become very hip in the capital, and Richard and I ate (and saw signs everywhere else for) the well-known "shui zhu yu"水煮鱼, fish which is poached and then marinated and served in really astonishingly "numbing and hot" ("ma la" 麻辣) oil, numbing by means of massive quantities of Sichuan pepper ("huajiao", Xanthoxylum piperitum, fagara pepper), import of which has, I gather been recently banned in the United States, which makes replicating the recipe (especially the "massive quantity" part) difficult here in the States, and indeed, may cause the gastronomic semantics of "Sichuan restaurant" in the US to change wildly in the next decade.

There. I got the word "semantics" into that last sentence, which makes this a legitimate language log post. Besides, as further evidence of linguistics at work (albeit linguists at play) we visited some products of what might be called "Ming Dynasty Applied Speech Science"; the famous Echo Wall at the Temple of Heaven park, the Three Sounds Stone and the amplifying platform on the Round Altar, presumably all cases of architectural acoustics designed give a little magical extra to whatever it is that Emperors say upon ritual harvest occasions.

But what makes it even more legitimate is the following tidbit, which arises from a visit that Richard, Chilin, their daughter Lisa, and I made to what is now called Prince Gong's residence. (This is one of the very many estates that claim, in a sort of Chinese version of "George Washington Slept Here", the honor of inspiring what many, including yours truly, consider The Greatest Novel Ever Written, Cao Xue Qin's Story of the Stone. For those of you who have somehow managed to miss this, I recommend the really astonishingly unfaithful but nevertheless incomparably wonderful translation by David Hawkes and John Minford).

Where was I? Oh yes. In the Qing dynasty. Now as legend has it (and I checked this on the web, so it must be true), it came to pass when the great Kang Xi emperor 康熙 (1622ish) was only sixteen that his grandmother fell ill. Kang Xi thereupon got brush, ink, and paper, and drew a large (2-foot-ish high) character, the word 'Fu' 福 , "fortune, well-being", and sent it to her. This was no ordinary Fu 福. No, Kang Xi managed in the cursive Fu-swirls to build in the character for "long life" (shou) as well, and indeed later scholars have identified in its lovely brush-strokes the characters for "child" (zi), "long life" (shou), "fields" (tian), "money" (cai), "more" (duo), plus a dot (dian) hence carrying the hidden meaning "More children, more money, more land, more life, more Fu, and a little more". As soon as she received this magical Fu 福, Kangxi's grandmother's health improved, whereupon Kang Xi knew that his calligraphy had magical powers. He therefore commanded that a large stone be brought (note to confused readers: this stone has nothing to do with the Story of the Stone mentioned above), and that a copy of his "Fu" 福 calligraphy be carved into the stone. Kang Xi died, and the stone was forgotten for two generations, until He Kun, the evil prime minister of the Qianlong emperor, heard of the magical powers of the "Fu 福", and managed to steal the stone from the court. (yes, yes, the old "evil court minister with magical powers" story. But He Kun was specially evil, and may be the origin of many evil court ministers in a whole bunch of really excellent wuxia (武俠; swordsman/knight-errant/martial arts) novels, such as my favorite, Louis Cha's (Jin Yong) The Deer and the Cauldron (鹿鼎記), also translated by John Minford).

But we digress. To hide the magic Fu 福, He Kun built a special cave in his gardens at his estate north of the palace, and placed the stele there in this special cave. It is not known what magical use He Kun made of the Fu 福 but eventually he died, and his mansion and gardens passed on to other inhabitants, and to make a long story, well, still pretty long, He Kun's estate is none other than Prince Gong's residence, and thus you may guess that the stone has since been found and was seen in person by Richard, Chilin, Lisa, and yours truly.

Zhou Enlai, the premier of China, later called this Fu 福 "the greatest Fu福 in China". According to some souvenirs that Richard, Chilin and I bought, it's in fact "the greatest Fu 福 in the world (天下第一福)", but between you and me, I suspect that this may just be marketing hype.

Here's a really ugly gaudy velveteen souvenir scroll of Kang Xi's magical Fu (yes, yes, this is a picture of a souvenir I actually paid money for, but I promise the real Fu, which is just stone, is much more beautiful, but I couldn't find a picture on the web). If you look really carefully, you can see the "greatest Fu 福 in the world (天下第一福)" part on the right.

A final linguistic tidbit about Fu 福. As all you Chinese speakers out there know, Fu is the character that you often see around New Years, on doors throughout China and Hong Kong, upside down, like this. This is because the word "dao4" means both "upside-down" (written 倒) and "arrives" (written 到), so the visual image of an upside-down Fu would be described verbally as "Fu2 dao4" which would then mean both "upside down Fu" and "fortune arrives". A nice example of a visual-verbal bimodal pun.

p.s. Anyhow, as Richard points out, if nothing else, our trip and this post have together clearly raised the bar on fu.

March 30, 2004

The Huntington Challenge

Robin Arnette has a long, thoughtful response (on the AAAS's MiSciNet) to Samuel Huntington's "Hispanic Challenge" article from Foreign Affairs. MiSciNet also provides links to six other rebuttals: Daniel Drezner, James Joyner, David Adesnik, The Economist, eRiposte, and the L.A. Times. It's interesting that four of the six are weblogs, and that those four are generally more informative and interesting than the two standard media treatments. No list of pro-Huntington weblogs is provided, though Russell Arben Fox can be found dusting off Herder for the occasion over at Wäldchen vom Philosophenweg.

Alleged Hispanic resistance to learning English is one of Huntington's central claims. Arnette argues against this view, as do most of the other rebutters cited, but it would be nice to see someone take Huntington to task in more factual detail, especially in terms of the alleged contrast between today's Hispanic immigrants and earlier generations of immigrants (this is a hint to Geoff Nunberg, who has composed a post answering this description, but has not yet pulled the trigger...). [Update: his post is here.]

Last month, I cited the contrast between liberal Democrat Huntington and conservative Republican Brooks on this issue. This seems to be one of the many questions on which it's hard to predict views based on location in a one-dimensional political subspace.

Though some things are predictable: Arnette bolsters her argument against Huntington's claims about language with a link to a Boston Globe article hosted on freerepublic.com, despite the fact that the following comments section is a sort of sewer of national stereotypes, nativist prejudices and curious linguistic misconceptions, with a few sensible observations bobbing in the flood.

Sunday's Garfield doesn't count

It has occurred to me that people who are prepared to accept the legend from a Garfield cartoon as respectable printed prose (which is plausible enough) might send me Sunday's Garfield strip, which had the eponymous feline glutton saying (over several panels):

I'm so hungry I could eat and eat and eat and eat and eat and eat and eat and eat and eat and eat and eat and eat and eat and eat and eat... But why stop there?

That might appear to be 15 coordinates, a super example to submit in response to my earlier musings.

Unfortunately, this doesn't count. It isn't true coordination. This is coordinative reduplication. The meaning is intensificatory: notice that I could eat and I could eat is just a redundant way to say I could eat, but I could eat and eat means more than that, it means something like "I could eat a whole lot." So I can't count that one.

Hunting for multiple-coordinate coordination constructions

I'm working with Rodney Huddleston on a textbook-size introduction to English grammar, and I recently came to a passage where we make and illustrate the point that coordinate structures don't appear to have any grammatical limit on the number of coordinate subparts. You get not just two coordinates (Starsky and Hutch) or three (The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly), or four (Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice), but any number. The temptation here is to show this by simply inventing boring examples with larger numbers of examples: We invited Bob, Carol, Ted, Alice, and Bruce (5 coordinates), and so on, and we were on the point of doing that, but it seemed to me it would be much better to illustrate with real examples. And it didn't take long to find a source with some real beauties.

You must understand, I'm not leaning toward corpus fetishism, the perverted insistence on using only real examples from a corpus of texts for your illustrations, no matter how much space that might waste. I just thought it would be livelier here to have some real, over-the-top examples of four, five, or six coordinates. And it was not hard to find them. For some reason, remembering some rich, ripe use of the English language, I took down from myself Lawrence Levine's The Opening of the American Mind. A quote I saw there led me to take down the book next to it, the one Levine is responding to: Allan Bloom's long, gloomy, preposterous jeremiad on everything wrong with American students, The Closing of the American Mind (1987). I really hit paydirt there. The extended polemic against rock music turned out to be particularly rich. These examples are all from pages 74 to 78:

- There is room only for the intense, changing, crude and immediate. [4 coordinates]

- People of future civilizations will wonder at this and find it as incomprehensible as we do the caste system, witch-burning, harems, cannibalism, and gladiatorial combats. [5 coordinates]

- Nothing noble, sublime, profound, delicate, tasteful or even decent can find a place in such tableaux. [6 coordinates]

Great stuff. When Bloom gets going, he really loses it, the old fool. His excess of rhetoric is as masturbatory as the state he claims rock music gets young people into. How did his ridiculous book ever become a best-seller? I don't know. But I cherish it as a fund of examples.

I'm now wondering if I could find Bloom using a 7-coordinate example. And I'm wondering about what might be the largest number of coordinates ever recorded in an attested example from broadly respectable printed prose.

Gosh, if I muse aloud like this, people may start emailing them to me. All they have to do is realize that my login name is probably pullum and that I'm well known to be at UCSC.edu — not that I'd ever reveal that on the web for fear of spambots.

In memoriam Larry Trask

We are deeply saddened to report that Larry Trask, a distinguished historical linguist and student of Basque, has passed away after a long illness. He made a strong and positive impression, not merely intellectual but personal, even on those who knew him only through his writing and correspondence. His Basque Language page contains much information about this often misunderstood language, including an excellent section on Prehistory and connections with other languages.

Here is an obituary written by his colleague Richard Coates at the University of Sussex, and here is an obituary in the newspaper Euskadi en el Mundo. Here is an interview with him published last summer in The Guardian.

The first self-writing weblog

Check out R. Robot ("He's the only columnist I'll read" -- Ann Coulter), and then the many fine links (and ideas!) in Cosma Shalizi's post on the topic. While you're there, scroll down for Cosma's recipe for miwa naurozi to celebrate the Afghan new year.

I tried the interactive feature, supplying "Geoff Pullum" as the requested name, which yielded this post (though permalinks don't seem to work on the site), beginning "Just what was Geoff Pullum trying to say yesterday?" and ending "There's Geoff Pullum at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco, making such inexplicable and execrable claims as, "Maybe we could get Iraq straightened out first," as he put it last week, and suggesting (with the internecine insouciance and contemptibly vile treachery that is his trademark, wont and fashion) that George Bush's moral leadership is for the purpose of votes."

I also recommend Newt Gingrich's memo "Language: a Key Mechanism of Control", which R. Robot cites a a source of inspiration and word lists. The link on R. Robot's index page appears to be broken, and for some reason the only copies I could find on line are on anti-Republican sites, who seem to find the memo more inspirational that GOP partisans do. Or maybe they don't need it anymore, I don't know.

Ten leading results in 20th century linguistics?

Lauren Slater's new book "Opening Skinner's Box", as described in this review by Peter Singer, sounds interesting:

The idea behind Lauren Slater's book is simple but ingenious: pluck 10 leading experiments in 20th-century psychology from the pages of the scientific journals in which they were first published, dust off the painfully academic style in which they were written up, add some personal details about the experimenters and retell them as intellectual adventures that help us to understand who we are and what our minds are like.

Now, it's clear that there are some issues about the actual content here. Slater has been accused of misunderstanding or misrepresenting some of the research she discusses, as well as some of her interviews with psychologists. See this Guardian review for some discussion, and look here for letters of complaint to her publisher from several of the psychologists whose interviews she described in the book, and here for an extended critique of a recent Guardian piece by Slater presenting material from one of the book's chapters. And according to this story, Deborah Skinner is suing over the way her upbringing (by B.F. Skinner) and its consequences are depicted in the book, for reasons she discusses in a Guardian piece entitled "I was not a lab rat." It sounds like psychology is not more reliably depicted by its popularizers than linguistics is.

I'm also not wild about the overall slant of Slater's choice of experiments (as describe in the reviews -- I haven't read the book). She focuses on clinical issues, especially pyschological damage allegedly due to bad parents and other authority figures. I don't have any problem with her choices taken individually -- all are interesting at least in a sociological sense, and most are scientifically interesting too. But her interest in mental health problems excludes neat (though less fraught) stuff like Fitts' Law (relating time, distance and target size for aimed movements), or the Rescorla-Wagner model of classical conditioning. This is a matter of taste, and her tastes are no doubt more popular than mine would be.

Anyhow, I like the "ten great experiments" concept. Not the "top ten" -- it's silly to try to map everything onto a single dimension of evaluation -- just a limited set of especially interesting and important things. As I was walking back from class this morning, I spent a few minutes thinking about what I'd pick as ten leading pieces of work in 20th-century linguistics.

I had no trouble coming up with a list -- the biggest problem is to trim it to ten -- and I'll tell you what it is in a later post. I'd be curious to hear what other people's suggestions are as well, so feel free to send me your ideas by email.

[Update 4/13/2004: The NYT has noticed the fuss about Slater's veracity, after Peter Singer totally missed it in his 3/18/2004 review. It's odd that he did so, since he himself notices that "Slater makes some errors that made me wonder about her accuracy in areas with which I am not familiar." The information was easy to find on the web a month ago. I guess he may have written the review before Deborah Skinner's 3/12/2004 Guardian piece appeared, but was it before Ian Pitchford's 3/2/2004 posting on psychiatry-research, or the late-February weblog posts by folks like Rivka? As a professor at Princeton, Singer doubtless knows how to research a subject; as a best-selling author, I bet he has assistants who can do it for him; this is supposed to be an area of expertise for him; I found everything cited here just by idly googling "Laura Slater"; was this really "due diligence"?]

Cartoons of the day

A Gricean evergreen, Pirates vs. Philosophers, accent and identity, and lexical innovation from "HER! Girl vs. Pig".

Jeniffer afficionados

Continuing the discussion of English orthographic gemination, Bill Poser observes that he sometimes finds himself writing "Jeniffer". This is not an experience that rings a bell for me, but Bill is clearly in tune with the zeitgeist, or anyhow the Jennifergeist:

f |

ff |

|

n |

869,000 |

481,000 |

nn |

15,400,000 |

120,000 |

Keith Ivey emailed to point out that "[t]wo accepted variant spellings of words borrowed from Spanish provide examples of an added geminate and a lost one: afficionado [and] guerilla." And notice that the result in each case is consistent with the orthographic pattern seen in the contingency tables for Attila, Karttunen and Jennifer: a preference for a single consonant paired in an adjacent syllable with a double one, in either order.

Qov emailed to say that "The ones I have to watch for are parallel, accelerate

and tomorrow. I don't

quite understand how the numbers in the tables prove your thesis, but Google

finds many more tommorows than tomorows and many more paralells than paralels."

Indeed, and also consider the relative paucity of "tommorrows". Here is the contingency table for tomorrow, which shows basically the same pattern that we've seen before:

| r | rr | |

| m | 67,700 |

14,300,000 |

| mm | 228,000 |

189,000 |

The case of variants for "parallel" is somewhat different, because there are apparently three different consonants involved to some extent in the confusions, and two of them are L's:

FORM |

ghits |

| paralel | 162,000 |

| paralell | 65,700 |

| parallel | 13,800,000 |

| parallell | 94,500 |

| parralel | 8,700 |

| parralell | 2,200 |

| parrallel | 31,200 |

| parrallell | 475 |

The analysis here is a bit more complicated -- maybe later, I have a grant proposal to write. I'll also see if I can find another, more accessible way to come at the explanation of the statistical analysis of contingency tables, to supplement the one I provided here

Saskatoon

Writing about the activities of the University of Saskatchewan Library reminded me of a joke. Since Geoff hasn't posted any bad linguistics jokes in quite a while, and most of our readers probably don't get much exposure to Canadian humour, I thought I'd tell a Saskatchewan joke.

Two Canadians, sick of the rat race, went to a travel agent and asked her to book them to the remotest place she could get them to by commercial air. Twenty-four hours later, they staggered off a plane in Alice Springs, Australia. Tired and thirsty, they headed for the nearest pub. It was obvious to the locals that they had come from somewhere distant, which led to much speculation. Finally, one of the locals said: "Let's settle this. I'll go over and ask them". He went over to their table and asked: "Where are you folks from?". They answered, "Saskatoon, Saskatchewan". When the local returned to his table, the others asked him: "So where are they from?". He answered: "I couldn't find out. They don't speak English.".

March 29, 2004

The Kamloops Wawa

The University of Saskatchewan Library recently acquired a full run of the Kamloops Wawa, a newspaper published primarily in Chinook Jargon between 1891 and 1923 in Kamloops, British Columbia. The information about the exhibit that the library put on to celebrate the new acquisition contains images of several pages.

Chinook Jargon is a pidgin based primarily on Chinook and Nuuchanulth (Nootka) that served as a trade language throughout the Pacific Northwest. Very few settlers learned the native languages, such as Secwepmectsín (Shuswap), the native language of the area around Kamloops, so Chinook Jargon played a major role in communication between settlers and native people.

The Kamloops Wawa was published in a French shorthand known as the Duployé shorthand,

which the Oblates of Mary Immaculate had decided was the easiest way to write the various

native languages that they dealt with in Southern British Columbia. They used this writing

system not only for Chinook Jargon but for English, French, Latin,

Lillooet,

Secwepmectsín (Shuswap), and

Nlaka'pamux (Thompson).

Here is the first page of the Shushwap Manual or Prayers, Hymns and Catechism, in Shushwap

published at Kamloops in 1906.

Duployé shorthand was a good writing system for the languages whose sound systems it was designed for, such as English. Indeed, because it was easier to write English in Duployé shorthand, which had no arbitrary spellings, than in the usual English spelling with which we are still encumbered, the Oblates encouraged settlers to learn it as a stepping-stone to English literacy. It was a less than adequate way of writing the native languages since it did not provide enough letters for all of their sounds.

The perils of degemination

In response to my recent post on conservation of gemination, Stefano Taschini has sent a stunning message that weaves together the themes of phonology, art, religion and female genitalia.

The point of my original piece was that English speakers sometimes seem to remember that a word like Attila has a double consonant in it somewhere, but get confused about just where it is. Stefano gives several other examples of the same sort, observing for example that "the differential equation studied by Jacopo Francesco Riccati registers about a thousand Google hits as 'Ricatti equation' (which is particularly disturbing, considered that 'ricatti' is the Italian for 'blackmail')". He also brings up some unexpected intrusions of (orthographic) gemination, asking how it happened that "the italian word 'regata' entered English as 'regatta'", and noting that there are 12,900 Google hits for "Gallileo."

The truly shocking news (for those of us who don't know Venetian slang) is at the end of his note:

A case of its own is the famous painting by Leonardo da Vinci, allegedly portraying a certain Monna Lisa (where Monna is the contraction of Madonna, i.e. My Lady) and known in the English-speaking world as Mona Lisa. Now, in the whole north-east of Italy, including Venice, "mona" is a rather obscene word denoting female pudenda, and, not unlike similar words in English, can be used by synecdoche to denote a woman. Referring to "Mona Lisa" in Venice can attract rather amused (or shocked) looks.

The Italian Wikipedia page for Monna Lisa includes the geminate, but the Dutch, German, Swedish and Hebrew Wikipedia pages on the same topic have only one N (or equivalent letter). French and Romanian of course have La Joconde and Gioconda respectively.

This merits a closer look, I can see. More later.

[Update: as for regatta, the OED blames it on the Italians, giving the etymology [It. (Venetian) regatta (and regata) 'a strife or contention or struggling for the maistrie' (Florio): hence also F. régate.] The earliest citation is late 17th century: 1652 S. S. Secretaries Studie 265 The rarest [show] that ever I saw, was a costly and ostentatious triumph, called a Regatto, presented on the Grand-Canal.

It's true that there is no regatta in contemporary Italian; was the 17th-century borrowing Regatto just a mistake?

I should also note that some northern Italian varieties don't have phonological geminate consonants at all, as I understand it. But perhaps those are the northwestern dialects. ]

[Update 3/30/2004: Des Small emailed this additional information about geminates in Venice:

I went to Venice last year for a conference (and accordingly saw approximately none of its glorious patrimony) and I took the Lonely Planet Italian phrasebook with me, so I could buy bus tickets (which is slightly non-trivial, as they are sold only in tobacconists' shops and never on buses), and I seem to remember it saying that Venetian dialect had _no_ geminates.

Given that I knew then exactly enough Italian to buy bus tickets and know less now, and I am not by any means a phonologist, that's also what I heard on the Venetian streets.

But the Internet agrees with me;

http://www.netaxs.com/~salvucci/ITALdial.html says:"Double consonants are to some extent singularized in Venetian: el galo (il

gallo), el leto (il letto); note also the use of the masculine article el

(il)."

while http://www.veneto.org/language/index.asp says

"[...] Venetian (spoken in Venice, Mestre and other towns along the coast).

It has 24 phonemes, seven vowels and 17 consonants; original Latin

plosives are softened and voiced and often disappear entirely; no double

consonants can be found;"Maybe Venetians reverentally resort to deobscenifying diglossia in cases of artistic appreciation; it can surely hardly be that the Internet is wrong!

So if Stefano is correct that "[r]eferring to 'Mona Lisa' in Venice can attract rather amused (or shocked) looks" -- and surely he must know -- then perhaps the references in question are in writing; or perhaps Des is right about facultative diglossia for aesthetic purposes; or perhaps the Venetians would be just as amused (or shocked) by references to 'Monna Lisa', if they should happen to hear any.]

Perl dictionary hacking

There's an interesting-looking article at perl.com by Sean Burke on how to render a dictionary represented in Shoebox format. I think that Burke's introduction rather exaggerates the general cluelessness of field linguists, many of whom are capable programmers themselves, or have previously teamed up with programmers to do similar things; but the article (which I haven't had time to read carefully yet) looks like it offers a good tutorial on how to use HTML or RTF to render a simple dictionary database for printing or on-screen reading.

As some of the (many available) examples of prior (and perhaps better) art, take a look at Bill Poser's lecture notes on extracting fields from Shoebox dictionaries using AWK (which unlike Burke's program, handles the case where there are repeated tags within an entry), or his paper "Lexical Databases for Carrier", or his "Poor man's Web Dictionary", which provides a working example of a simple pure HTML (no CGI, no database) lexicon generated automatically from a Shoebox database, together with the code necessary to generate it. Although simple, it includes audio and images.

Google's print edition

If you have plenty of bookshelf space, you may be interested in Google's print edition .

The quantitative side of the ad is a bit under-researched, even for a joke. In particular, the claim that "Google's 36,795 volumes will be ten times larger than the unabridged Oxford English Dictionary" seems simultaneously to attribute far too few volumes to Google and far too many to the OED.

Conservation of (orthographic) gemination

Lauri Karttunen once remarked to me that Americans, who misspell his last name a lot, render it as "Kartunnen" more often than as "Kartunen". That is, rather than just omitting the doubled letter T, they substitute a doubled letter N instead. This is not a mistake that any native speaker of Finnish is likely to make,but non-Finns seem to remember that there's a double letter in there somewhere, even if they aren't very sure where it is.

I thought of this the other day, because in a post about Attila the Hun, in which the name "Attila" occurred a half a dozen times, I misspelled it once as "Atilla". I noticed the error and corrected it, even before Geoff Pullum did. But meanwhile, David Pesetsky had emailed me with important movie lore. He first copied my error, and then immediately correctly himself: "Did I really just spell Attila with one T and two L's? I do know better." Well, both of us do, but our pattern of typos still exhibited Lauri's hypothesized conversation of gemination.

Despite Lauri's many contributions, I feared that the name Karttunen would not occur often enough on the internet to check his intuition statistically. But Attila is another matter.

When I queried Google a few days ago, I got the following page counts:

String |

Ghits |

| "atila the hun" | 989 |

| "attila the hun" | 43,300 |

| "atilla the hun" | 9,400 |

| "attilla the hun" | 2,400 |

I didn't go any further with the issue then, but this evening I'm riding Amtrak

from Washington to Philly, and so I have a few minutes to play with the numbers.

Arranging the counts in a 2x2 table, and giving the row and column sums as well as the overall total, we get:

l |

ll |

||

t |

989 |

9,400 |

10,389 |

tt |

43,300 |

2.400 |

45,700 |

44,289 |

11,800 |

56,089 |

One sensible way to view this set of outcomes is as the results of two independent choices, made every time the word is spelled: whether or not to double the T, and whether or not to double the L. After all, every one of the four possible outcomes occurs fairly often. This is the kind of model of typographical divergences -- whether caused by slips of fingers, slips of the brain, or wrong beliefs about what the right pattern is -- that underlies most spelling-correction algorithms.

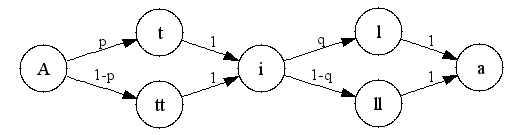

In the case of the four spellings of Attila, we can represent the options as a finite automaton, as shown below:

There are four possible paths from the start of this network (at the left) to the end (at the right). Leaving the initial "A", we can take the path with probability p that leads to a single "t", or the alternative path with probability 1-p that leads to a double "tt". There is another choice point after the "i", where we can head for the single "l" with probability q, or to the double "ll" with probability 1-q. In this simple model, the markovian (independence) assumption means that when we make the choice between "l" and "ll", we take no account at all of the choice that we previously made between "t" and "tt".

But are these two choices independent in fact? If Lauri was right about the "conservation of gemination", then the two choices are not being made independent of one another. Writers will be less likely to choose "ll" if they've chosen "tt", and more likely to choose "ll" if they've chosen "t".

There are several simple ways to get a sense of whether the independence assumption is working out. Maybe the easiest one is to note that in the model above, the predicted string probabilities for the four outcomes are

l |

ll |

|

t |

pq |

p(1-q) |

tt |

(1-p)q |

(1-p)(1-q) |

This makes it easy to see that (if the model holds) the column-wise ratios of counts should be constant. In other words, if we call the 2x2 table of counts C, then C(1,1)/C(2,1) (i.e. atila/attila) should be pq/((1-p)q) = p/(1-p), while C(1,2)/C(2,2) (i.e. atilla/attilla) should be (p(1-q))/((1-p)(1-q)) = p/(1-p) also. We can check this easily: atila/attila is 989/43,300 = .023,while atilla/attilla is 9,400/2,400 = 3.9.

The same sort of thing applies if we look at the ratios row-wise: C(1,1)/C(1,2) (i.e. atila/atilla) should be pq/((p(1-q)) = q/(1-q), while C(2,1)/C(2,2) (i.e. attila/attilla) should be ((1-p)q)/((1-p)(1-q)), or q/(1-q) also. Checking this empirically, we find that atila/atilla is 989/9,400 = .105, while attila/attilla is 43,300/2,400 = 18.0.

Well, .023 seems very different from 3.9, while .105 seems very different from 18.0. But are they different enough for us to conclude that the independence assumption is wrong? or could these divergences plausibly have arisen by chance?

The exact test for this question is called "Fisher's Exact Test" (as discussed in mathworld, and in this course description for the 2x2 case). If we apply this test to the 2x2 table of "attila"-spelling data, it tells us that if the underlying process really involved two independent choices, the observed counts would be this far from the predictions with p = < 2.2e-16, or roughly 1 in 500 quadrillion times. In other words, the choices are not being made independently!

The direction of the deviations from the predictions also confirms Lauri's hypothesis -- writers have a strong tendency to prefer exactly one double letter in the sequence, even though zero and two do occur. Given that the two-independent-choices model is obviously wrong, there are other questions we'd like to ask about what is right. But with only four numbers to work with, there are too many hypotheses in this particular case, and not enough data to constrain them very tightly.

However, there's a lot of information out there on the net, in principle, about what kinds of spelling alternatives do occur, and what their co-occurrence patterns look like. The key problem is how to tell that a given string at a given point in a text is actually an attempt to spell some specified word-form. We've solved that problem here by looking for patterns like "a[t]+i[l]+a the hun" (not that Google will let us use a pattern like that directly, alas). In other cases, we would have to find some method for determining the intended lemma and morphological form for a given (possibly misspelled) string in context. This is not impossible but the general case is certainly not solved, or spelling correction programs would be much better than they are.

[Update: I was completely wrong about the possibility of checking this idea with web counts of the name Karttunen and its variants. We have

Karttunen 57,500

Kartunnen 3,330

Karttunnen 156

Kartunen 628

or in tabular form

n |

nn |

|

| t | 628 |

3,330 |

| tt | 57,500 |

156 |

There is a small problem: many of these are actually valid spellings of other people's names (even if historically derived from spelling errors at Ellis Island or wherever), rather than misspellings of Karttunen. Still, the result also supports Lauri's hypothesis, and I have no doubt that it would continue to do so if the data were cleaned up.]

March 28, 2004

Speech Accent Archive

The Speech Accent Archive at George Mason University is a neat idea. But it seems to be based on the premise of providing one exemplar of each place of origin -- for countries where there are multiple speakers, each one is identified as being from a unique city or town. This makes it less than optimally useful for studies of variable phenomena, for studies of things that depend on level of experience with English, and so on.

It'd also be nice to be able to get the audio in a convenient form, for further analysis. The quicktime .mov format in which they're stored is not among the more widely recognized formats, at least by audio analysis programs.

Bad named entity algorithms at the Gray Lady?

The first paragraph of a story in today's NYT by David Carr, entitled "Casting Reality TV becomes a Science", reads, in the online version, like this:

In a suite high above Columbus Circle, Rob LaPlante is looking for next season's breakout television star. There is no agent hovering nearby, no technical crew, just Mr. LaPlante, his assistant and a digital video camera, auditioning Laura Fluor, a car saleswoman from Monmouth County, N.J.

The hyperlink on Laura's last name "Fluor" leads to a page about the Fluor Corporation on the NYT business site, giving us the standard NYT "Company Research" treatment: share price and price history information, a thumbnail description of the company's business ("The Group's principal activities are to provide professional services on a global basis in the fields of engineering, procurement, construction and maintenance...") a list of the latest insider trades, and so on. A similar page is available for any company traded on the major stock exchanges.

There is absolutely nothing in the original Carr article to lead us to believe that Laura Fluor has anything at all to do with the Fluor Corporation. I can't imagine that the writer, an editor or even any human hyperlinker would think that this link was appropriate. So either someone is having a little joke, or the NYT's online site is running some company-name-recognition software that needs work. The state of the art for "entity tagging" is far from perfect, but it's better than this.

And yet.

How many times does a word or phrase need to be repeated in order to seem characteristic of a speaker or author? I think that the answer is "not very many times, maybe only once or twice, if the use in context is salient enough".

If this is true, then the kind of statistical stylistics that David Lodge worried about will not be adequate to uncover these associations. Raw frequencies certainly will not work, since these words or phrases may only be used a couple of times, or at least will only have been used a couple of times at the point where we start to associate them with the writer or speaker. Simple ratios of observed frequencies to general expectations will not work either, because at counts of two or so, such tests will pick out far too many words and phrases whose expected frequency over the span of text in question is nearly zero. As readers and listeners, we mostly ignore these cases, attributing them to the influence of topic or to random noise in the process. To model human reactions in such cases, we need to be able to discount the effects of topic, and perhaps also to understand better, in some other ways, what makes the use of a word or phrase stylistically striking or salient.

I recently came across an example of this phenomenon in the climactic scene of Jennifer Government, a satirical SF novel by Max Barry. This is the end of chapter 84, p. 313, where the book's eponymous heroine Jennifer Government arrests the arch-villain, her former lover John Nike:

... "John Nike, you are under arrest for the murder of Hayley McDonald's and up to fourteen other people."

"What? What?"

"You will be held by the Government until the victim's families can commence prosecution against you." She hauled him up and marched him towards the escalators. He was a pain to move. His legs kept slipping out from under him, as if he was drunk.

"You're arresting me? Are you serious? I don't belong in jail!"

"And yet," she said.

When I read this passage, I recognized that "and yet" -- as a phrase by itself, with the continuation left unspoken -- was an expression characteristic of the character "Jennifer". I couldn't remember any specific instances from earlier in the book where she had used the expression, though I did feel that one of them had been in a conversation with her four-year-old daughter Kate.

Courtesy of amazon.com's search function, I can easily find out how often the expression occurs elsewhere in the book. The answer is "twice". The first is indeed part of Jennifer's effort to get her daughter up in the morning, on p. 170:

Kate's eyes opened, then squeezed closed. "I'm tired..."

"It's time to get ready for school."

"I don't want to."

"And yet," she said.

The second instance is in the context of a government raid on General Motors' London headquarters (p. 195):

In a way, Jennifer felt bad, busting into such a nice place in full riot gear and scaring the crap out of everybody. But in another, more accurate way, she enjoyed it a lot. She collared a scared-looking receptionist and read out her list of target executives. "Where are they?"

"They're--different floors. Four, eight and nine."

"Three teams!" Jennifer said. "I'll take level nine. Meet back here."

"You can't go up there!" the receptionist said, horrified. "This is private property! You can't!"

"And yet," Jennifer said. She hit the stairs. She found her target by striding down the corridor and barking out his name: when a man popped his head out of an office, she cuffed him. It was much easier than she'd expected.

It seems fairly easy to explain post hoc why the phrase "and yet" as a sentence in itself should trigger our linguistic novelty detectors -- the words in this case are clearly free of topic-specific content, and the bigram "and yet" at the end of sentence, written without continuation dots, is much rarer than would be predicted given its overall frequency and the frequency of sentence-ends. However, I suspect that a scan for bigrams with quantitatively similar properties would turn up lots of unremarkable examples, and that other examples of passages evoking a similar psychological reaction might not yield as easily to simple frequentistic analysis, even post hoc.

This reminds me of Josh Tenenbaum's analysis of generalization from very small sets, down to sets of size one. It would be interesting to try an analogous approach here. A more strictly analogous problem would be inferring the 'sense' of a word or phrase from a single use in context. This is related to the point under discussion here, I think, since in many cases we seem to identify a speaker or writer's lexical habit from a couple of uses, in part by concluding that those uses constitute a novel (or at least unusual) sense.

I should point out that Max Barry (the author of Jennifer Government) tries to salt the mine, so to speak, by having the little girl in the first passage cited above respond "Mommy, I hate it when you say 'And yet.'", thus trying to clue us in overtly to his intentions. I don't think this is necessary or even effective -- I don't think it had any effect on my reactions in this case.

And yet.

No, the context isn't quite right for this to be a valid instance of Jennifer's little verbal tic, as established by the three examples in the novel. In fact, I think that any one of those examples would probably do as an adequate basis for lexicographic generalization, suggesting that my use in the preceding paragraph, though plausible enough, is not the same sense. In some sense.

Searching for Santa Cruz

A new

service

for searching language archives has just been set up on the

LDC website.

Enter a language name like Warlpiri, to find 41 results in

7 different language archives, ranging from a bunch of primary

resources in the

Australian

Studies Electronic Data Archive, to a paper in the

ACL Anthology

on "Parsing a Free-Word Order Language." If you use a variant or

incorrect spelling of the language name (e.g. Walbiri), the

service will direct you to the correct version, thanks to

Ethnologue's list of alternate

language names, approximate string matching, and various other tricks.

Enter a country name

to find resources for languages spoken in that country.

Search for Santa Cruz (a language of the Solomon Islands) and find

Voorhoeve and Wurm's recordings held in the

Pacific And Regional Archive for Digital Sources in Endangered Cultures.

Now try the same

search using Google, to discover a host of irrelevant sites (like the UCSC homepage) and realize the value of having this new service

which searches a union catalog

of major language archives. Visit LINGUIST List for

a more

fine-grained interface for searching within the same collection.

All this is made possible by OLAC, the

Open Language Archives Community...

A new

service

for searching language archives has just been set up on the

LDC website.

Enter a language name like Warlpiri, to find 41 results in

7 different language archives, ranging from a bunch of primary

resources in the

Australian

Studies Electronic Data Archive, to a paper in the

ACL Anthology

on "Parsing a Free-Word Order Language." If you use a variant or

incorrect spelling of the language name (e.g. Walbiri), the

service will direct you to the correct version, thanks to

Ethnologue's list of alternate

language names, approximate string matching, and various other tricks.

Enter a country name

to find resources for languages spoken in that country.

Search for Santa Cruz (a language of the Solomon Islands) and find

Voorhoeve and Wurm's recordings held in the

Pacific And Regional Archive for Digital Sources in Endangered Cultures.

Now try the same

search using Google, to discover a host of irrelevant sites (like the UCSC homepage) and realize the value of having this new service

which searches a union catalog

of major language archives. Visit LINGUIST List for

a more

fine-grained interface for searching within the same collection.

All this is made possible by OLAC, the

Open Language Archives Community...

Back in October Mark Liberman wrote: "One thing I'd like to understand better is the relationship to the Open Archives Initiative and the Open Language Archives Community. Steven?" (Another scientific revolution?). Later Mark gave OLAC some more air-time: "The OLAC Metadata set is a modest set of extensions to the Dublin Core, useful for cataloguing language-related archives of various types" (Borges on metadata). Let me take this as my cue to tell you some more about OLAC.

In December 2000, an NSF-funded Workshop on Web-Based Language Documentation and Description, held in Philadelphia, brought together a group of nearly 100 language software developers, linguists, and archivists responsible for creating language resources in North America, South America, Europe, Africa, the Middle East, Asia, and Australia. The outcome of the workshop was the founding of the Open Language Archives Community, with the following purpose:

OLAC, the Open Language Archives Community, is an international partnership of institutions and individuals who are creating a worldwide virtual library of language resources by: (i) developing consensus on best current practice for the digital archiving of language resources, and (ii) developing a network of interoperating repositories and services for housing and accessing such resources.

Today OLAC has over two dozen participating archives in seven countries, with 26,656 records describing language resource holdings. Anyone in the wider linguistics community can participate, not only by using the search facilities, but also by documenting their own resources (providing data), or by helping create and evaluate new best practice recommendations (sign up for OLAC mailing lists, starting with OLAC General).

OLAC is built on two frameworks developed within the digital libraries community by the Dublin Core Metadata Initiative and the Open Archives Initiative. The DCMI provides a way to represent metadata in electronic form, while the OAI provides a convenient method to aggregate metadata from multiple archives.

"Metadata" is structured data about data - descriptive information about a physical object or a digital resource. Library card catalogs are a well-established type of metadata, and they have served as collection management and resource discovery tools for decades. The OLAC Metadata standard defines the elements to be used in descriptions of language archive holdings, and how such descriptions are to be disseminated using XML descriptive markup for harvesting by service providers in the language resources community. The OLAC metadata set contains the 15 elements of the Dublin Core metadata set plus several refined elements that capture information of special interest to the language resources community. In order to improve recall and precision when searching for resources, the standard also defines controlled vocabularies for descriptor terms covering language identifiers, linguistic data types, discourse types, linguistic fields, and participant roles. You can see three of these vocabularies in use by searching for Pullum and picking the record for Pullum & Derbyshire's paper Object-initial languages.

I'm indebted to Gary Simons, along with dozens of institutions and individuals for helping to build and support OLAC.

March 27, 2004

Onion entropy

Just when I thought the Onion was getting predictable, we get this.

Slyly carrying on the joke, Classics in Contemporary Culture observes that "someone has the rudiments of Greek grammar, but doesn't know about final sigmas...", but one of the commenters suggests that "The text was probably created with Symbol, which IIRC doesn't include a final sigma."

X are from Mars, Y are from Venus

Back in November of 2003, this weblog post (by journalist Gavin Sheridan) accused author John Gray of exaggerating his educational credentials. Well, to be more precise, it called him a "fraud" for claiming a PhD from "Columbia Pacific University", which was shut down by the state of California in 2000 for "award[ing] excessive credit for prior experiential learning to many students; fail[ing] to employ duly qualified faculty; and fail[ing] to meet various requirements for issuing Ph.D. degrees." Gray apparently had some lawyers issue a threatening letter, which included the additional information that his B.A. and M.A. are from "Maharishi European Research University". The result has been to publicize the questions about Gray's credentials much more widely, since the story was picked up by Glen Reynolds (here and here) among others.

Gray is the author of the "Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus" series, popularizing a version of the "two cultures" (or in this case perhaps "two planets") theories about inter-gender communication, originated in an academically more serious form by Deborah Tannen and others. That's a topic for another post -- the only new thing that I've learned about it from reading the blog entries cited above is that Gray's own communications skills are apparently so finely tuned that he's been able to talk his way through eight marriages. Here I'm just registering another sign of his success as a communicator, namely the spread of the "X are from Mars, Y are from Venus" snowclone.

A bit of internet searching turns up X/Y pairs from many domains, including

suppliers/buyers

customers/suppliers

buyers/brokers

distributors/manufacturersmedia/scientists

scientists/journalists

students/teachers

teachers/pupils

scientists/educators

physical scientists/mathematicians

pathologists/clinicians

developers/testers

lawyers/doctors

directors/actorsRepublicans/Democrats

Americans/Europeans

Germans/Italians

Nikes/Reeboks

web searchers/ browsers

PCs/MacsDogs/Cats

mandrills/lemurs

bulls/cows

humans/monkeys

As far as I know, this formula is original to Gray (unless it was suggested by some anonymous editor or editorial lackey). I'm not convinced that theories of inter-cultural communication have significantly improved relationships between any of the X's and Y's in the list, but I could be wrong.

March 26, 2004

What that wooden stake is really for

Those who have been following the vampire language saga (here and here) on Prentiss Riddle's blog will want to take a look at this report from Walachia, south of Transylvania. Apparently in this culture, vampires only prey on their families:

"That's the problem with vampires," said Doru Morinescu, a 30-year-old shepherd who, like many in the village, has a family connection to the current case. "They'd be all right if you could set them after your enemies. But they only kill loved ones. I can understand why, but they have to be stopped."

The methods for dealing with vampires are also not quite as Bram Stoker depicted them.

"Before the burial, you can insert a long sewing needle, just into the bellybutton," he said. "That will stop them from becoming a vampire."

But once they've become vampires, all that's left is to dig them up, use a curved haying sickle to remove the heart, burn the heart to ashes on an iron plate, then have the ill relatives drink the ashes mixed with water.

"The heart of a vampire, while you burn it, will squeak like a mouse and try to escape," Balasa said. "It's best to take a wooden stake and pin it to the pan, so it won't get away."

I'm not sure that I see just how to pin something to an iron plate with a wooden stake. I can see why the reporter didn't ask more about this -- it's the sort of thing that easier to demonstrate than to describe effectively. Whatever the proper technique, it's illegal in Romania, where local authorities are threatening to file charges against the relatives of alleged vampire Toma Petre.

"What did we do?" pleaded Flora Marinescu, Petre's sister and the wife of the man accused of re-killing him. "If they're right, he was already dead. If we're right, we killed a vampire and saved three lives. ... Is that so wrong?"

[news tip from John Bell]

March 25, 2004

Diamond geezer?

Among the "over-used phrases" that the Plain English Campaign has cited as as "a barrier to communication" is diamond geezer. This one is so far from being over-used, at least in the circles that I inhabit, that the obstacle it poses to communication is that I've never heard of it and have no idea what it means.

A Google search turns up 23,000 pages, of which the first few include a weblog featuring London sitcoms, restaurant reviews, railway security and "street cries of old/new London;" a jewelry store "tirelessly scouring the world to match you with your perfect diamond"; a site that identifies the term diamond geezer with people who wear brightly-colored harlequin trousers in support of a rugby team; and a music promoter offering expertise in "2 Step, Bhangra, Bungati, Charts, Dance, Disco, Drum and Bass, Dub, Funk, Garage, Hard House, Hip Hop, House, Indie, Jungle, Live Music, Miami Base, Old Skool, Old Skool (Drum & Bass), R&B, Ragga, Reggae, Rock, Salsa/Latin, Soul, Swing, Techno, Trance".

At this point, my ability to form natural classes has been already been stretched beyond its limits. This phrase is not an irritatingly overused and tired cliché, it's a complete f***ing mystery. I see confirmation here for my original conjecture that the whole Plain English Campaign thing is an elaborate Pythonic joke. Can someone offer a clue?

[Update: many clues have been offered. Anders suggests that I "have a butcher's" at this page, which glosses diamond geezer as "A really wonderful man, helpful and reliable; a gem of a man. A commonly heard extension to 'diamond'. [Mainly London use]".

John Kozak explains that

It's East End slang. "geezer" = "man", in a "one-of-us" sort of way. Here, "diamond" is approbatory, so the overall sense is "a good sort". There's a slight overlay to all this in that most people's exposure to this term is via an interminable set of films sponsored by the public lottery about East End gangsters, so most would situate it more narrowly in that context.

John goes on to ask "In the US, 'geezer' = 'old person', doesn't it? Wonder how that came about? "

And Des Small writes that

This is Cockney/London slang for "great bloke". Since you obviously can't go around believing random stuff that people tell you, here's a link to a source:

http://www.LondonSlang.com/db/d/

"""

diamond geezer - - a good 'solid' reliable person.

"""

It's on the Internet, so it must be true!

Thanks to all!

]

[Update 2: The OED glosses geezer as "A term of derision applied esp. to men, usu. but not necessarily elderly; a chap, fellow. " Its first citation is from 1885. Of the ten citations, four (including the first) explicitly say "old" in association with geezer, and I think that all are British sources. One of the citations is "1893 Northumbld. Gloss., Geezer, a mummer; and hence any grotesque or queer character. " This suggests the equation grotesque = old as the source of the association with old age. In (my intuitions about) American usage, this association has become part of the core meaning of the word, and to use geezer for a child or youth would have to be a joke or other special effect.]

That queerest of all the queer things in this world

Last November, I suggested that ambient cell phone conversations are distracting and annoying not because they're loud, but because they're one-sided and therefore frustrating to try to follow. In 1880, Mark Twain wrote a "comic sketch" about the experience of listening to one side of a "telephonic conversation" in which he makes a similar point.

I handed the telephone to the applicant, and sat down. Then followed that queerest of all the queer things in this world—a conversation with only one end to it. You hear questions asked; you don’t hear the answer. You hear invitations given; you hear no thanks in return. You have listening pauses of dead silence, followed by apparently irrelevant and unjustifiable exclamations of glad surprise or sorrow or dismay. You can’t make head or tail of the talk, because you never hear anything that the person at the other end of the wire says.

He goes on to give a complete transcript of his end of this particular conversation. Some aspects of the piece are dated -- the interaction with the central office, the need to shout to be heard down an unamplified phone line, and Twain's casual display of sexist stereotypes, which today is permitted in our better publications only when directed at men. But the experience is basically1 the same today as it was 124 years ago.

1The Plain English Campaign thinks

that basically is "irritating". I think it's the right

word in this context, meaning (as the American Heritage Dictionary tells us)

"In a basic way; fundamentally or essentially".

Sapir-Whorf alert

The April Scientific American has a feature on Paul Kay, discussing his research before and after Basic Color Terms in 1969. An interesting quote:

"Two key questions must always be kept separate," Kay adds. "One is, do different languages give rise to different ways of thought? The other is, how different are languages?" It is possible, he says, that the respective answers are "yes" and "not very."

We've discussed related issues in the past (here and here, for example). A current controversies has to do with differences in spatial reference -- the relative role of cultural, linguistic and situational factors is debated, with different experiments pointing in different directions (so to speak). More on this soon.

More on the McGurk Effect

The McGurk effect to which Sally Thomason refers, whereby someone presented with a video of a person saying [ga] and simultaneous audio of someone saying [ba], perceives [da], is indeed interesting, and has been exploited in various ways to get at aspects of speech perception. You can find out more about it from this web page at Haskins Laboratories, which includes this link to a demonstration of the effect.

Irritating cliches? Get a life

The Plain English Campaign is not just an amiable bunch of British eccentrics, says Mark (here); they are humorless hypocrites, "short on judgment, common sense and consistency", and their pronouncements, themselves laden with clichés, are not to be taken seriously. I agree, of course. Don't just listen to me about the Campaign's indefensible citation of Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld for an allegedly confusing pronouncement; listen to The Economist , which loves to mock Americans and word-manglers, but agreed with me on this.)

The Campaign's list of the most irritating clichés in the English language does include some clichéd phrases that I can imagine people being irritated by. Their number one, the (largely British) phrase at the end of the day — which I understand to have a meaning somewhere in the same region as after all, all in all, the bottom line is, and when the chips are down — may shock people by its complete bleaching away of temporal meaning. As I understand it, users of this phrase would see nothing at all peculiar in a sentence like It's no good saving money on heating if it means having a cold bedroom, because at the end of the day, you've got to get up in the morning.

The second-ranked at this moment in time might annoy people by being a six-syllable substitute for the monosyllabic now — though this has happened before: Colonel Potter in the TV series MASH used to say WW2, a seven-syllable abbreviation for the three-syllable full-length version World War Two.

However, some of the other items on the list are surely just incorrectly classified: as I understand what a cliché is, many of these aren't clichés at all. They're just words some people have taken an irrational dislike to. That's very different. A few examples follow:

- The adverb absolutely.

- The adjective awesome.

- The adverb basically.

- The noun basis.

- The adverb literally.

- The adjective ongoing.

- The verb prioritize.

A cliché is a trite, hackneyed, stereotyped, or threadbare phrase or expression: spoiled from long familiarity, worn out from over-use, no longer fresh. But if the Plain English Campaign is going to claim the right to say that about individual words that its correspondents suddenly take a disfancy to, surely most of the words found in smaller dictionaries will have to go. Many of the words we use -- like every single one of the words in this sentence -- have been around and in constant use for several hundred years. What on earth is the Plain English Campaign suggesting we should do with its list of pet hates? Is it recommending word taboos on the basis of voting out, a kind of lexical Survivor?

And what is getting the poor loser words voted off the island? Why, for instance, should a persistent problem be permitted to persist while the ongoing use of an ongoing problem is condemned? Of the two, persistent is the older, hence presumably the staler.

But the Campaign can't really be worried about staleness. Another of their picks is just one of the half-dozen uses of like. The unpopular use is of course the one where it is a hedge meaning something like "this may not be exactly the right word but it gives the general impression." I discussed it here, and later discovered that it is actually used by God. An odd choice indeed as a cliché: the one thing everyone agrees on is that it is fairly new in the language. I figured that was why it was hated so much. What's supposed to be wrong with these condemned items: are they too old or too new?

I don't understand these wordgripers and phrase disparagers. If I may borrow a phrase that genuinely is hackneyed and familiar (immortalized in William Shatner's wonderful Saturday Night Live Trekkies sketch and none the worse for its frequent affectionate requotation): people, get a life.

Baba vs. Dada

Back in the days when I taught a Phonetics class (because I was in a department that had no genuine phonetician, the kind of person who is not a technophobe and can introduce students to the wonders of phonetics software), I used to give my students an emphatic warning: when you work on your term project, I told them, do tape-record your consultant pronouncing a 200-word Swadesh list of basic vocabulary, but don't use those tapes as a substitute for face-to-face elicitation and checking of data. The reason is that seeing your consultant pronounce the sounds helps you hear them better and identify them correctly. Yesterday I began to doubt the complete wisdom of this advice when my colleague Pam Beddor showed a video in which a lecturer illustrated the McGurk effect. Probably all my fellow bloggers already know about this remarkable demonstration, but I'll describe it anyway.

The speaker announced that she would pronounce a nonsense word, baba. She instructed her audience to close their eyes and listen. Sure enough, with your eyes closed, you could tell that she was saying baba. No surprise there. Then the audience was told to listen again with open eyes. This time the video showed the speaker apparently pronouncing dada -- no lip closure at all, though I couldn't actually see much of what was going on behind the teeth. And in fact I heard dada. No matter how hard I tried, knowing that she was actually saying baba, I could not hear baba. True, it sounded like a slightly odd version of dada, or at least I imagined that it sounded oddish, but I couldn't even imagine baba while watching her. Moral (?): in a clash between eyes and ears, the eyes have it.

[Update by Mark Liberman: Sally is right to be impressed by the McGurk effect -- it's a stunning demonstration of the power of "sensory fusion" in speech perception. However, her description of the details is a bit different from the way in which the standard effect is usually demonstrated. The standard McGurk effect involves seeing a video of [ga] while listening to a synchonized audio of [ba] and perceiving [da], unless you close your eyes. It feels like you're controlling the playback with your eyelids.

There's a excellent McGurk page

here.]

Bored of

A recent post on wordorigins discusses "bored of" as opposed to "bored with". This one strikes me just like "worried of" (discussed here and here) and "eligible of" (discussed here) -- in other words, ungrammatical.

However, Google gets 162,000 hits for "bored of". Lots are "Bored of the Rings" and such-like bad puns, but quite a few are things like "If you are bored of your computer, Desktop Studio can help you." The search also turned up a year-old article entitled "Unnatural Language Processing", by Michael Rundell, that treats this very topic. Rundell observes that

When the British National Corpus (BNC) was assembled in the early 1990s, there were 246 instances of 'bored with', but only 10 hits for 'bored of' -- and most of these came from recorded conversations rather than from written texts. The bored of variant would still, I suspect, be regarded as incorrect by most teachers, but a search on Google finds 112,000 instances of this pairing, as against 340,000 examples of bored with. It is always a bad idea to make predictions about language, but bored of seems to be catching up with bored with, and may well end up being recognized as an acceptable alternative.

It would be neat if this were true, though I'm afraid that Rundell may have been fooled by the "Bored of the Rings" and "Bored of Ed" jokes. It's not totally impossible, though -- "bored of it" now gets 25,400 ghits, whereas "bored with it" gets 48,500 , barely 1.9 times more. All the more reason to look carefully at verb/preposition associations across time, space and genre. Human Social Dynamics, yo.

[Update 3.29.2004: "bored of it" in a cartoon here.]

March 24, 2004

Big of a deal

Mary at eyes.puzzling.org asks "Is "big of a deal" as in 'it's not that big of a deal' a US usage, or am I just missing out on a trend?"

Kenneth Wilson discusses this in The Columbia Guide to Standard American English:

of a occurs more and more frequently in Nonstandard Common and Vulgar English in uses such as It’s not that big of a deal; She didn’t give too long of a talk; How hard of a job do you think it’ll be? All these are analogous to How much of a job will it be?, which is clearly idiomatic and Standard, at least in the spoken language where it most frequently occurs. It is possible, therefore, that the first three could achieve idiomatic status too before long, despite the objections of many commentators.

Another possible source is suggested by an observation attributed to Groucho Marx:

Outside of a dog, a man's best friend is a book. Inside of a dog, it's too dark to read.

It's interesting that Wilson's examples all involve positive-end scalar predicates: big, long, hard. The adjectives from the other ends of such scales show up less often in this construction, both absolutely and in proportion to the frequency of each particular adjective itself. The numbers below are Google hits (which are document counts rather than word or phrase counts, but they'll do):

| ADJ of a | ADJ | |

| big | 161,000 |

133M |

| small | 18,500 |

116M |

| hard | 10,300 |

89.5M |

| easy | 4,020 |

79.6M |

| far | 9,120 |

62.1M |

| near | 624 |

48.8M |

The case of long and short is a problem, because "short of a" has another meaning that is very common, as in "one can short of a six pack" or "just short of a miracle". We can avoid this by checking "too long of a" and "too short of a", which show the same effect, as do heavy and light:

| too ADJ of a | ADJ | |

| long | 12,400 |

152M |

| short | 5,830 |

69.2M |

| heavy | 1,540 |

27.5M |

| light | 690 |

77.2M |

Cuteness

Rachel Shallit posts here and here about an interesting new morphological fad: "X + ness = X, which I am trying to be funny or cute about". This has something to do with the cutesy snowclone "crunchy X goodness", as in "CSS, XSLT, XUL, HTML, XHTML, MathML, SVG, and lots of other crunchy XML goodness", or "Shoggoth.net is filled to the brim with crunchy Cthulhu goodness" or "Now with more crunchy sarcastic goodness in every bite", or "this week, I have nearly 300 pages of crunchy Economist goodness to read." For some crunchy goodness from nearly 30 years ago, look here.

Fed up with "fed up"?