December 31, 2006

Busy tongues

The latest instance of "Everyone already knows this" commentary on The Female Brain comes from Cinnamon Stillwell in the SF Examiner, 12/29/2006, under the headline "Experts Discover Men And Women Are Different!":

When it was revealed that scientific studies published in the new book "The Female Brain" demonstrate that women talk more than men, many of us responded with a collective shrug. Anyone who has ever been in a relationship with a member of the opposite sex -- whether romantic, familial or friendly -- knows that women talk more than men. A lot more.

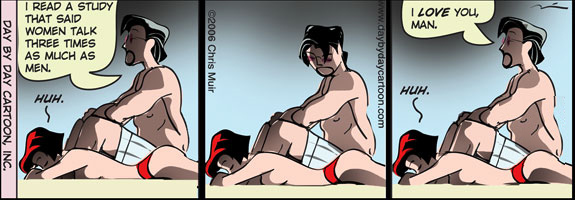

"The Female Brain" indicates that not only do women talk three times as much as men, but they also get a chemical rush in their brains from hearing their own voices. This may explain why women describe "feeling better" after talking about problems or issues in their lives, beyond the mere relief of getting it off their chest.

The "revelation" behind the hyperlink is the Daily Mail article that I discussed around Thanksgiving ("Regression to the mean in British journalism", 11/28/2006). Brief recap: Louann Brizendine neither did nor cited any "scientific studies" about sex and talkativeness, but just invented some numbers out of thin air -- or maybe quoted someone else who invented the numbers. She's semi-retracted the claim. And the "chemical rush" business is apparently just as bogus -- see the links collected here for some discussion.

But let's light a scientific candle instead of cursing the journalistic darkness.

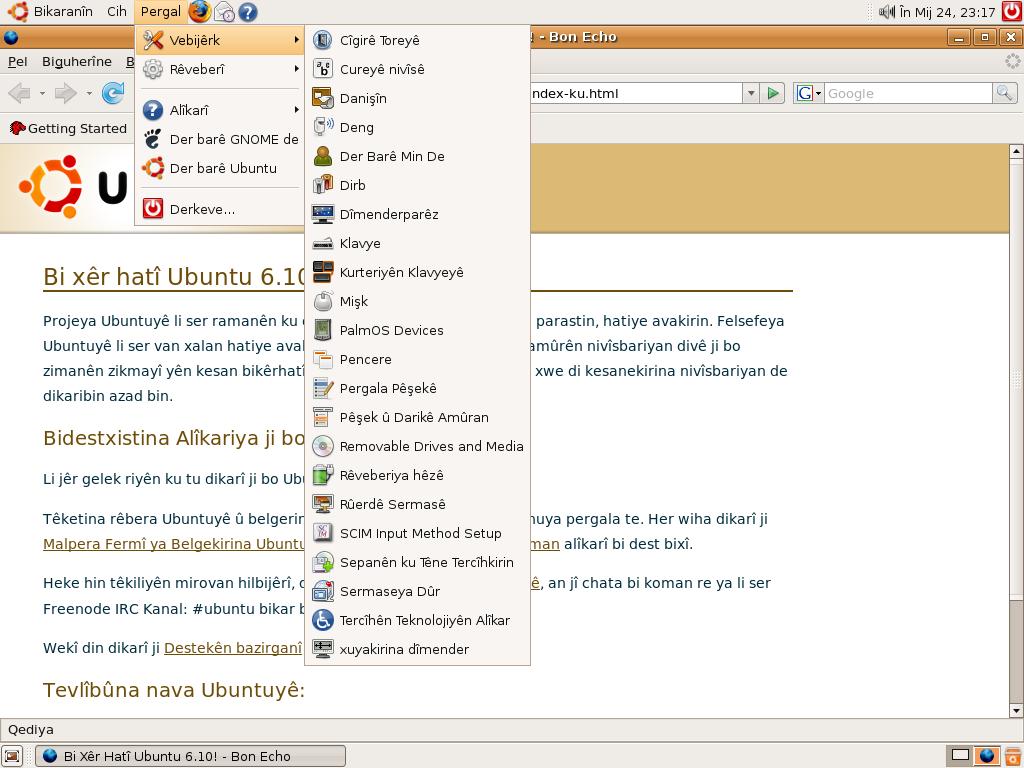

In an earlier post ("Gabby guys: the effect size", 9/23/2006), I discussed some data from the Fisher English Corpus Part 1 (FECP1), a collection of 5,850 telephone conversations lasting up to 10 minutes each, recorded in 2003. 10,950 of 11,700 conversational sides involved native speakers of American English for whom information about sex, age and years of education is available, I've posted a summary of data from those calls here. Each line presents information about one conversational side, laid out like this:

sex no. of turns no. of words total time words per min. ID age years of edu m 149 773 208.5 222.446 2602 34 16 f 138 876 212.26 247.621 1790 24 16

One simple thing we can do with this data is to fit a linear regression model. A script for the free software statistics package R, which will read in the data and fit such a model, is here. Type the R expression

summary(M1 <- lm(words ~ sex + age + edu + sex:age + sex:edu - 1))

(it's in the script as well) and you'll learn:

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

sexf 731.1017 21.7214 33.658 < 2e-16 ***

sexm 808.0448 26.2205 30.817 < 2e-16 ***

age 2.5811 0.2945 8.765 < 2e-16 ***

edu 4.3731 1.2402 3.526 0.000424 ***

sexm:age -0.2608 0.4285 -0.609 0.542853

sexm:edu -1.6424 2.0538 -0.800 0.423915

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 288.2 on 10944 degrees of freedom Multiple R-Squared: 0.909, Adjusted R-squared: 0.909 F-statistic: 1.822e+04 on 6 and 10944 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

The effects of sex, age and education were highly "significant" in the technical statistical sense. Whether these effects were significant in the ordinary language sense, you can judge for yourself. The sex-age and sex-education interactions were not significant.

Your basic modeled male put out about 77 more words per conversation than your basic modeled female did -- 808 vs. 731, or about 10% more. And independent of sex, each additional year of age was worth about 2.6 additional words per conversation, while each additional year of formal education was worth about 4.4 additional words. A light-hearted way to put this would be that being male is worth about 30 years of experience (76.9/2.58 = 29.8) or 18 years of formal education (76.9/4.37 = 17.6 ). In terms of word count in a 10-minute phone conversation, that is... [Emily Bender has written to warn me that irony is dangerous, and I risk having my numbers quoted by the BBC or the AP, along the lines of "From the point of view of verbal facility, being male is worth 30 years of practice or 18 years of formal education, according to research published this month". We'll see...]

Once again, young men talk like old women. But we already knew that, right?

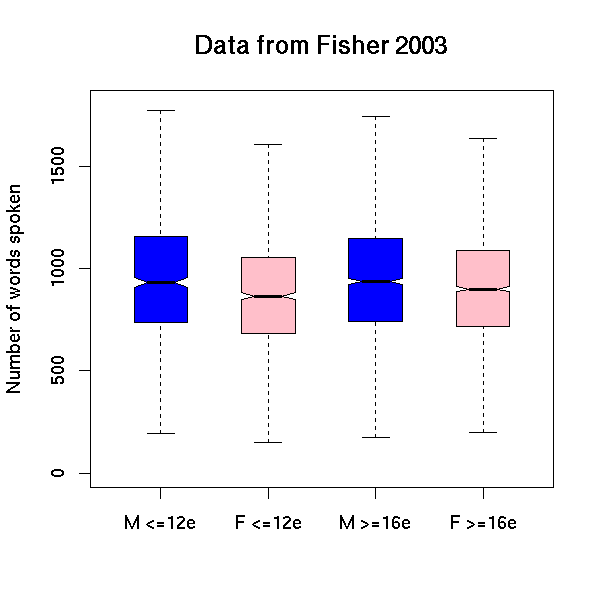

Here's a boxplot to help you judge the size of the sex and education effects. The top and bottom of the box are the 75th and 25th percentiles; the whiskers extend out to the edges of the range, once some statistical outliers have been trimmed. The four boxes show males and females over the age of 25 with a high school education or less, vs. with a college degree or more. (The script also includes the code to generate this plot -- you can make your own plot for the sex and age effects...)

[Update -- several people, including Geoff Pullum, have copied me on email sent to Cinnamon Stillwell, clueing her in to the non-existence of the "science" confirming what she thinks everyone "knows", and to the contrary results of such studies as do actually exist. She hasn't responded yet, but in fact Steven Colbert has already scripted the response that I expect:

And on this show, on this show your voice will be heard... in the form of my voice. 'Cause you're looking at a straight-shooter, America. I tell it like it is. I calls 'em like I sees 'em. I will speak to you in plain simple English.And that brings us to tonight's word: truthiness.

Now I'm sure some of the Word Police, the wordanistas over at Webster's, are gonna say, "Hey, that's not a word." Well, anybody who knows me knows that I'm no fan of dictionaries or reference books. They're elitist. Constantly telling us what is or isn't true, or what did or didn't happen. Who's Britannica to tell me the Panama Canal was finished in 1914? If I wanna say it happened in 1941, that's my right. I don't trust books. They're all fact, no heart.

And in their hearts, everybody knows that "women talk more than men. A lot more." And blacks are lazy, jews are avaricious, celts are drunks, southerners are stupid... You can't fight truthiness -- or the pop psychology books that promote it. Don't be fooled by the long list of scientific-looking references -- The Female Brain and its ilk might be books that invoke the authority of science, but they're all heart, no fact.]

December 30, 2006

Cool Hwip: the culture of a cluster

Family Guy is contending with The Simpsons as a source of materials for linguistics instruction. Last time the subject was uptalk ("Satirical cartoon uptalk is not HRT either") -- this time it's [h] before semivowels:

The classic reference on this topic is Raven McDavid Jr. and Virginia Glen McDavid, "H before Semivowels in the Eastern United States", Language 28(1) 41-62 (1952):

Although the pronunciation of /h-/ before vowels does not constitute a social shibboleth in the United States, there is evidence that the presence or absence of /h-/ in words like whip and humor is often considered a test of social acceptability. Thus when Thomas Pyles recently remarked that in his dialect (of Frederick, Maryland) the cluster /hw-/ does not occur, despite the efforts of well-meaning schoolteachers to impose it on generations of students, a reader immediately commented that nowhere had she observed a person of true culture who did not possess that cluster. Such responses are not confined to laymen. T. R. Lounsbury and William Dwight Whitney, and more recently C. K. Thomas and A. G. Kennedy, have insisted that there is a social stigma attached to those who do not pronounce /h-/ in words of these types. H. L. Mencken, on the other hand, considers the pronunciation of /h-/ in whip etc. an affectation.

I'm with Thomas Pyles and H. L. Mencken on this one -- "the baby whales" and "the baby wails" are homophonous in my speech. And at least some of Family Guy's target demographic is way beyond Mencken, considering [hw-] not affected but just plain hweird.

Here's McDavid & McDavid's hypothesis about the history:

By the time of the American Revolution neither the restoration of /h-/ in humor as a spelling-pronunciation nor the simplification of /hw-/ to /w-/ had been carried out in the cultured speech of southern England. Consequently it is easy to understand both the overwhelming preference of American speakers for humor with /j-/, and the fact that the areas with /w-/ in whip, wheelbarrow, whetstone, and whinny center around the ports, where contact with England was longest maintained by the mercantile class.

A (nonlinguist) guest brought /hw-/ up at dinner last night, and responses around the table made it clear that plenty of Americans still preserve this feature, hweird as it may sound to some.

[Hat tip: Vishy Venugopalan]

[For more on this, see Roger Shuy's post "Wut? Wen? Wich?", 9/17/2006.]

[Update -- Tiago Tresoldi writes:

a great post, but the video was cut and people who did not watch the show are probably not getting the "you are eating hair": in fact, Meg (the sister) had put some of her hair inside the pie. That is why Stewie (the baby) is eating "hair" and not "air".

The beginning is available here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uDH7ASzdQ7k

]

Phonics

We've never had a Swedish cartoon before. This Jan Stenmark example, sent in by Anastasia Nylund, didn't seem very funny at first, but it's been growing on me:

"Daddy, how do you spell 'steam train'?"

"The way it sounds."

"Choo-choo-choo?"

Francis Strand offers some advice about how to pronounce Swedish spelling. Sample:

G - same as English before an A, O, U or Å; but before an E, I, Y, Ä or Ö it is pronounced more or less like a y; it's like in English before consonants, except when at the end of words such as berg or borg, where it sort of disappears as you almost make a y sound but don't really; the other consonant exception is when it comes before an N, such as in barnvagn - baby carriage - the combination of gn becomes like ngn. Finally, it sometimes doesn't follow these rules at all.

Francis has been blogging since August, 2001, under the title "How to learn Swedish in 1000 difficult lessons", providing one Swedish word or phrase in each post.

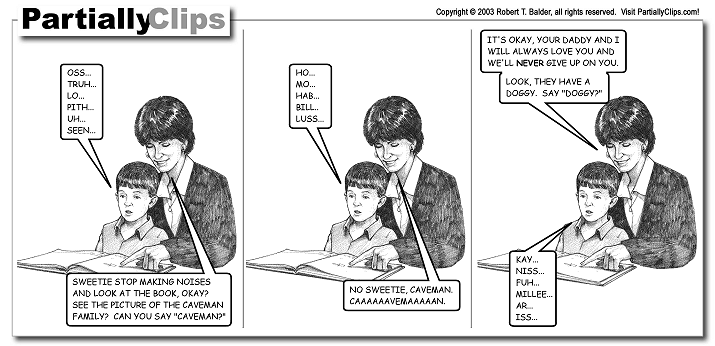

This might be our first Swedish cartoon, but it's not our first phonics cartoon, which was Rob Balder's' "Boy Reading" (from Partially Clips, 7/21/2202), and is worth posting again:

For some excellent (though unfortunately cartoon-free) background, read this.

Vocabulary size and country music

The Economist ("Middle America's soul", 23 December 2006, 45-47) quotes a contemptuous Bob Newhart joke about country music:

"I don't like country music, but I don't mean to denigrate those who do. And for the people who like country music, denigrate means ‘put down’."

Never mind the target of the joke (Newhart is probably satirizing the familiar blue-state bi-coastal snooty attitude toward c&w rather than endorsing it); let's think about its basis. Once again, it's vocabulary size as the measure of intelligence and wisdom and culture, isn't it?

Despite the fact that we have virtually no idea of how to measure vocabulary size rigorously and fairly (which is one thing differentiating vocabulary size from penis length), nobody cares: people are prepared (it would seem) to accept imaginary facts about how many words are known by groups of people about whom they know nothing (or about themselves, as with the Payack claims concerning English) as a reliable assay of intelligence level, or even the sophistication level of a whole language or culture, and to accept any kind raving nonsense anyone comes up with by way of vocabulary counting. The Reader's Digest word quiz is headed "It Pays to Increase Your Word Power": just sock those words away like cash in a bank. And Will Shortz's puzzles on NPR's Weekend Edition Sunday (how I hate that puzzle segment) are nearly always about rapid lexical access. It's the central stereotypical yardstick for how smart you are among ordinary people: how many words you have, and how quickly you can come up with the right one to name the right kind of snow or whatever. Newhart's joke reminded me again of how superficial lexicon size measurement is as a surrogate for intelligence, and how common it is to find journalists writing things (of either the many-words-for-X or the no-word-for-X variety) that suggest they accept it.

December 29, 2006

The silence of the men

The pseudo-scientific urban legends about sex differences in talkativeness are mutating slightly as they spread around the world. The most recent variants can be found in a 12/22/2006 article in Die Welt: Von Heike Stüvel, "Das Schweigen der Männer" ("The Silence of Men"):

Amerikanische Forscher haben herausgefunden: Männer sprechen im Durchschnitt ein Sechstel weniger als Frauen. Die einzige Ausnahme sind Telefonate mit dem Handy.

Frauen sprechen im Schnitt 30.000 Wörter am Tag, Männer 25 000. Nur ein Viertel redet über Sorgen und Probleme. Am Telefon werden Männer redseliger. Sie benutzen ihr Handy häufiger als Frauen und führen damit im Schnitt 88 Telefonate die Woche.

American researchers have discovered: Men speak on average a sixth less than women. The only exceptions are mobile telephone calls.

Women speak on average 30,000 words a day, men 25,000. Only a quarter [of men] disucss their concerns and problems. On the telephone, men become more talkative. They use their mobile phones more than women and make on average 88 calls a week.

The 30,000/25,000 is a pair of numbers that I haven't seen yet -- there are dozens of pairs (and ranges) of numbers out there among the replications of this meme, among them 20,000/7,000; 30,000/15,000; 7,000/2,000; 30,000/12,000; 50,000/25,000; 25,000/12,000. But I haven't seen 30,000/25,000 before.

Who are the "Amerikanische Forscher" I wonder, and where do the words-per-day and the cell phone counts come from, I wonder? This Swiss study supports the view that college-age males, at least, might make more cell phone calls:

The Die Welt article might not tell us where its words-per-day and cell-phone usage numbers come from, but a few paragraphs in, some familar names show up:

Männer und Frauen sind - was das Kommunizieren betrifft - komplett verschieden. Obwohl Frau und Mann häufig dieselben Worte verwenden, meinen Sie selten das Gleiche. Woher kommt das?

Die US-Neurologin Louann Brizendine fand heraus: Das weibliche Gehirn hat im Sprachzentrum elf Prozent mehr Nervenzellen als das männliche - besonders im Bereich, der für Gefühle und Erinnerungen zuständig ist. Warum Männer oft nicht zuhören, haben Forscher auch herausgefunden: "Frauenstimmen sind aufgrund der Stimmbänder und des Kehlkopfs komplexer und melodiöser als Männerstimmen", so Michael Hunter von der Universität Sheffield. [...]

Das Gehirn wird durch die verschiedenen Schallwellen stärker beansprucht - das fordert viel Konzentration und führt bei Männern zur Ermüdung.

Where communication is concerned, men and women are completely different. Although women and men often use the same words, they seldom mean the same thing. Why is that?

The American neurologist Louann Brizendine has discovered: The female brain has 11% more nerve cells in the language center than the male does -- especially in the area that is responsible for feelings and memories. Researchers have also discovered why men often do not hear: "Because of the vocal cords and the larynx, women's voices are more complex and more melodious than men's voices", says Michael Hunter of the University of Sheffield.

The brain is more strongly stressed by varying sound waves -- this demands concentration and makes men tired.

Right. The "11% more nerve cells" part is bogus, though again I'm not sure exactly where it comes from. For a discussion of some of the parts of Louann Brizendine's book about the language-related areas of the brain, see here and here. (Dr. Brizendine hasn't done any research of her own on this topic.) None of Michael Hunter's research, as far as I'm aware, establishes anything about degrees of concentration or men getting tired or (in fact) anything about differences in men's perception vs. women's perception. For a discussion of Michael Hunter's work on (men's) perception of different sorts of voices, see here and here.

The Die Welt article ends with familiar stuff about how women express feelings, and men express facts, and that's all because of the paleolithic division of labor, in which men were responsible for hunting bison and "Frauen waren eher für Kinder, Küche, Kirche... oops I mean Hege, Pflege und Gefühle" ("women were instead for nurturing, care and feelings").

I think of Die Welt as a serious, reponsible publication. Wikipedia calls it "the flagship publication, within the so-called quality newspaper market, of the Axel Springer empire". It's disconcerting to see such a paper spreading apparently fabricated numbers without any serious attempt at attribution or any fact-checking at all.

There's a lot of hand-wringing these days about the sinking fortunes of print media. It's usual to blame competition from new sources of information. But I wonder how much of the problem is epitomized in articles like this one. Maybe the public has more sense than the journalists do.

December 28, 2006

Two ways to look at the passive

Since we last looked at the injunction Avoid Passive in any detail (in a posting by Mark Liberman that has links back to a pile of earlier postings), I've looked at some more treatments of the passive in books of advice. Here I'm going to report on two extremes: at the low end, Toni Boyle and K.D. Sullivan, The Gremlins of Grammar: A Guide to Conquering the Mischievous Myths That Plague American English (2006), and at the very high end, Virginia Tufte, Artful Sentences: Syntax as Style (also 2006). The two books share a semantic characterization of the passive, but otherwise they could scarcely be more different.

I'm going to follow both of the books in talking about the "passive voice", though older writers on English grammar (especially in the 19th century) regularly object to this term, on the grounds that voice and tense and mood and aspect and the like are names of grammatical categories realized in inflectional morphology. Latin has a passive voice, these writers explain, because it has a system of inflected verb forms that are primarily devoted to use in constructions of a certain sort. English, on the other hand, has constructions of this sort, but no verb form primarily devoted to use in them; the English passive (as in This book was written by a friend of mine) uses the "past participle" (to give it its traditional, and very opaque, name), which is also used in perfect-aspect clauses (like Kim has written many books) and adjectivals (like Written instructions are better than oral ones and When we arrived, at 5, the door was closed and locked). To put things another way, the work that's done by inflectional morphology in Latin is done in English "analytically", or "periphrastically", that is, by syntactic constructions.

What is this work? Simplifying a lot, the passive provides a way to treat what is normally the direct object of a verb (or, occasionally, the object of a preposition) as a subject. Note that my characterization is framed entirely in syntactic terms: the syntactic category verb and the syntactic functions subject, direct object, and prepositional object. There is no talk of actions, actors, agents, performers of actions, or recipients of actions. (These semantic notions are not irrelevant, because they're tied, in very complex ways, to the syntactic notions of subject, direct object, etc. They're just not identical to them.)

English has a number of constructions that do this work. Among them are several that use the past participle form of the verb and optionally allow the expression of the normal subject in a prepositional phrase with by (in actual writing and speech, the by-phrase is much more often omitted than not). I will refer to all of these as "passive constructions". Among them are the "BE-passive" in (1) and the "GET-passive" in (2):

(2) Kim got attacked by wolves.

There's now a problem in using the technical term "active (voice)". It contrasts with "passive (voice)", but how? Is it narrowly contrasted, so that active VPs are only the ones that can have passive counterparts? If so, then enormous numbers of verbs are neither active nor passive: in particular, intransitives of several types, as in (3), and unpassivizable transitives of several types, as in (4).

(3b) Sandy disappeared.

(3c) Terry seemed unhappy.

(3d) Chris became a detective.

(3e) Three hours elapsed.

(3f) Terry screamed.

(4a) Kim resembles Sandy. (*Sandy is resembled by Terry.)

(4b) The play concerns poverty. (*Poverty is concerned by the play.)

(4c) I realized the answer. (*The answer was realized by me.)

(4d) These movies star Freddy the Pig. (*Freddy the Pig is starred by these movies.)

(4e) I have two houses. (*Two houses are had by me.)

Or is "active" broadly contrasted to "passive", so that anything that's not passive is active? If so, then intransitives and unpassivizable transitives are all active. In this case, we might as well abandon the misleading technical term "active" completely: VPs are either passive or not; the non-passive VPs don't necessarily have anything in common with one another, beyond not being passive.

This is all background. Now a word about the attitude we take at Language Log to the passive, which is that passive constructions have their uses and that a blanket injunction to avoid them, or even to avoid them as much as possible, is silly. Good writers, including Strunk and White themselves, use them with some frequency, as we have pointed out many times here on Language Log. In fact, most of Tufte's discussion of the passive (pp. 78-89) is devoted to its virtues, with many well-chosen examples.

(Quite often, people have written me to say that in their experience active clauses are usually, or even almost always, clearer than their passive counterparts. These are, of course, impressions, not the results of systematic studies of passive use; they are subject to the effects of selective attention and confirmation bias. When people have looked at polished writing to count passive clauses -- not an easy task, and subject to some judgment calls -- they find that 10-20% of the clauses are passive. And when you look at specific examples, very few of them would be improved by conversion to actives, and many would be changed for the worse.)

It is true that some writers seem to be overfond of the passive, and can use some encouragement to re-word. My impression, from working with students, is that the problem is rarely a simple fondness for passives, but usually involves a more complex set of difficulties in organizing discourses for an audience. The ineffective passives are just a symptom of a larger problem.

Now to the two books. Gremlins has a very brief treatment, less than a page (pp. 77-8). The section, titled "Verbs Have Voices", starts with an explanation of the voices of English:

(The usual confusion between expressions and the things they denote, between words and the world. Subjects of sentences are linguistic expressions, and expressions don't do actions; denotations of subjects might sometimes do actions, however. This usage is so widespread that it might seen churlish to complain about it. But I think it's useful for students to keep the distinction between form and meaning in mind; remember that this is a book for ordinary people, not professional linguists or philosophers. Once that's well established, there's no problem in using the looser locution, since things will be clear in context.)

Ok, Gremlins talks about "verbs", period, suggesting that they hold to the view that all verbs are either passive or not, and they use "active" to refer to the non-passive ones. That's just a terminological choice. Then they give a version of the standard semantic characterization, in which verbs denote actions and subjects of active verbs denote the agents in those actions, and one example. The example has four active VPs in coordination, sharing the subject the matador. The first two of these can be seen as denoting actions only by stretching the notion of "action" considerably; confronting something and staring something in the eye are not caused changes of state. It is, of course, easy to find much more extreme examples, of active VPs that transparently do not denote caused changes of state: many of those in (3) and (4) above, plus things like:

(5b) The tank holds 14 gallons.

(5c) Everyone appreciates fine wines.

(5d) Fine wines please everyone.

(5e) Picnics attract ants.

When you look at polished writing and ask how many clauses have verbs denoting actions and subjects denoting the agent of those actions -- again, not an easy task and subject to judgment calls -- the figures are once more in the 10-20% range. Action verbs with agentive subjects are certainly not in the majority.

I'm dwelling on these very familiar points because the characterization and the example appear in a book of advice; they're SUPPOSED TO BE HELPFUL to writers. I can't imagine how they could be. The semantic characterization is no more than recitation of a piece of a catechism, reproduced without understanding; a reader who takes it to be a claim about English (or languages in general) and tries to test it will quickly come upon examples like those above and conclude that the claim is false, while everyone else will just memorize it as a definition and pass on, no wiser. But why do semantic characterizations persist, in the face of such abundant counterevidence?

I suspect that the answer is in fact that they are treated as dogma. They are seen as being so fundamentally true that action and doer of the action have come to be understood as 'meaning of a verb' and 'meaning of a subject in an active clause', respectively. Plenty of people have responded to examples like those in (4) and (5) by patiently explaining to me that they do indeed describe actions, in some extended or metaphorical interpretation of the word action. For them, the semantic characterizations couldn't possibly be false. If so, then including them in an advice book is nothing more than instruction in the catechism.

In any case, Gremlins passes immediately to the passive, leading with:

A quibble: "some tense" should be "some form". Is written and was written have tensed forms of BE (present and past, respectively), but be written (base form), being written (present participle), and been written (past participle) do not, yet all of them are passive. A small point, true, but also another instance of the often shocking laxness in the use of standard grammatical terminology in popular writing ABOUT GRAMMAR.

More important, we've already seen that passive verbs don't always use some form of BE; there's also the GET-passive, as in (2). In fact, there's a whole lot more -- in particular, BE-less passives in various verb-complement constructions, as in (6), and in various free adjunct constructions, as in (7).

(6b) We saw Kim attacked by wolves.

(7a) Attacked by wolves, Kim fled.

(7b) With Kim attacked by wolves, everyone was terrified.

(7c) Once attacked by wolves, you'll never feel the same about the forest.

And there are many constructions with the verb BE in them that are also not passives -- the progressive, in (8), and an assortment of copular constructions, sampled in (9).

(9a) Terry is unhappy.

(9b) Superman is Clark Kent in disguise.

(9c) There are penguins on the porch.

I mention all this because Gremlins has, for some reason, taken the occurrence of a form of BE as criterial for passives, when in fact it is neither necessary nor sufficient.

Meanwhile, there are several constructions involving subjects that are understood as objects of verbs, but are in fact NOT passive constructions, for example the four illustrated in (10), in which the subjects are understood as object of the verbs read, skim, lift, and wash, respectively.

(10b) This book is easy to skim.

(10c) This box is too heavy to lift.

(10d) My shirt needs washing.

But all of these details are as nothing in the face of the fact that this section of the book is the first place in it where passives are mentioned, and the fact that the two short passages above (three sentences of text in all) are the whole of the book's treatment of the nature of active and passive voice. Obviously, no one could make any sense of this if they didn't already know how to recognize actives and passives, at least in the easy cases, so what is this section for?

The point is to trumpet Avoid Passive (which is what comes next); the stuff about be is there, I think, just as a demonstration that serious grammatical issues are somehow involved. The tactic here is one I've seen in a number of popular advice books (I hope to post on some other examples eventually): the goal of a section of the book is to proscribe some usage, but first there are some ornamental technicalities, which serve to suggest that the proscription is somehow grounded in Real Grammar and therefore should be taken seriously. The ornamental technicalities are, typically, one or more of the following: truncated (Gremlins on the passive might be a new record here); therefore desperately incomplete; inaccurate on factual details; illustrated by flawed examples; discussed with technical terms used inappropriately; and not entirely relevant to the proscription. Oh yes, and the examples are almost always invented and almost always given without context.

In any case, the punch line is:

Then there's the bad-mouthing of music in minor keys. Undeniably, minor scales and chords are popularly associated with melancholy, but there's plenty of minor music with other emotional tones (Beethoven's Fifth Symphony is in C minor, a key that many have seen as characteristically "stormy" and "heroic" for Beethoven), and most music of any length modulates between minor and major (sometimes shorter compositions do too; as Daniel Levitin notes in This Is Your Brain on Music, p.38, "Light My Fire" by the Doors has the verses in minor chords, but the chorus in major chords).

And then the analogy between passive syntax and minor music, which seems to turn on perceived associations between passivity, in the real world, and, on the one hand, passive syntax, and, on the other, minor keys -- in combination with a celebration of activity, energy, control, etc. in the real world, which are associated with active syntax and major keys. There's a lot to be said on the topic -- why, for example, is the contrast not between restiveness (bad) and placidity (good)? -- but, as far as I'm concerned, none of it belongs in a book like Gremlins. There might indeed be some metaphorical associations, between grammatical voice and extralinguistic matters, that have some psychological reality for at least some speakers, but they're likely to be subtle in their effects, much more subtle than other factors that I'll take up below.

Finally, a comment on "the subject of a passive voice never acts". For passivizable verbs with non-agentive subjects, the passives are just as (metaphorically) "active" as the corresponding actives, as is the case for (5c) and (5d) and their passives:

(5c - passive) Fine wines are appreciated by everyone.

(5d - active) Fine wines please everyone.

(5d - passive) Everyone is pleased by fine wines.

As far as I know, there are no verbs with agentive direct objects -- there is, after all, SOME significant connection between the syntactic functions in sentences and the participant roles in situations -- but you can concoct passives in which the subject denotes an agent, just not the agent of the verb that is passivized. What I have in mind are things like:

Here the impulse or inspiration is internal to the speaker of (11). The effect of the sentence is to assert that the speaker sang the national anthem -- performed an action -- and did so as a result of this internal impulse or inspiration.

Back to the Gremlins text. The activity connection is pursued further in its final part:

You want others to remember what you say and write, so keep it active. The exercise will do you good.

Taking it from the end: the activity connection is there in the pun on exercise; and the preceding sentence introduces a new (and unsubstantiated) claim, that active sentences are easier to remember than passive sentences. Now consider the passive example, (I). It is indeed awkward, but that's at least in part because the book that was written in four weeks is hard to contextualize. (It's only too easy to invent awkward examples, especially out of context.) If the referent of the book is given in the context (as it must be in (II)), then the following (which also makes the contrast explicit) is something of an improvement:

In (III), the restrictive relative clause (modifying the book) that makes the original hard to contextualize has been turned into the first conjunct of a coordination; the Gremlins rewriting, (II), does the same. That is, (II) is not a simple "turning around" of passives into actives; that would produce something like

in which, as in (I), the contrast between four weeks and four years is poorly expressed, because four weeks is inside a relative clause and four years is in the main clause. A minimal fix would put the two NPs in parallel positions:

(where X is some subject NP). Converting a passive with no by-phrase into an active requires supplying material not in the original; in this case, Gremlins supplies, without comment, a subject she.

But (V) implies (almost surely incorrectly) that the person who wrote the book also made the movie of it. Version (IV) shares this defect, but there's no such problem with (III), since (III) contains no NPs denoting the writer of the book or the maker of the movie. That's one of the virtues of the passive: it allows you to omit any expression of the subject of its active counterpart. In any case, fixing the problem with (V) requires you to supply different subjects for wrote and made:

The first lesson here is that rewriting to avoid some proscribed usage often requires rewording other parts of the sentence, sometimes substantially. Advice manuals almost always do this subsidiary rewriting without comment, though if readers need advice on using actives and passives they almost surely need help in the rewriting process.

Now look at the first conjuncts in (III) and (VI): the book was written in four weeks (passive) vs. X wrote the book in four weeks (active). These clauses are not interchangeable in discourse, because the passive version is about the book, while the active version is likely to be understood as being about X; in general, a subject is likely to be understood as denoting something that is both topical in the sentence (what the sentence is about) and topical in the discourse (what the discourse is about at this point). That's another of the virtues of the passive: it allows you convey that a certain discourse referent (denoted by the subject of the passive) is topical. Gremlins, like most advice on the choice between active and passive, fails to even hint at the enormous importance of topicality in this choice.

Next, look at the second conjunct in (VI) -- and Y made it into a movie in four years -- and compare it to the active Gremlins version, (II), and the improved passive version, (III). As I've already pointed out, (II) and (III) bring out the contrast between four weeks and four years by using but instead of and. This is another way in which rewriting can introduce material not explicit in the original. That's the second lesson here: advice manuals very often make alterations in the original that are not required by a straightforward undoing of the proscribed usage; they "improve" the original in other ways as well and so heighten the contrast between the "bad" original and its rewriting (almost always without comment or explanation, of course).

In fact, the second conjunct of the Gremlins version, (II) -- but it took four years to make the movie -- goes way beyond the minimal rewriting in (VI). Strikingly, (VI) has an action verb and an agentive subject in this conjunct, but (II) does not! The verb in (II), took, is indeed active voice, but in the sense here TAKE belongs with the verbs in (5) above, which don't even come close to denoting actions. In fact, in this sense, TAKE is unpassivizable (with either of the two available verbs):

(12b) *Four years were taken (by it) to make the movie.

(12c) *The movie was taken (by it) four years to make.

As for the subject, it's a "dummy" it, a place-holder with no denotation of its own (certainly not as an agent in an action); instead, in this construction to make the movie 'making the movie' is interpreted as the subject of took four years. The verb TAKE in related constructions, as in (13) and (14), is equally unpassivizable:

(13b) *Four years were taken (by making the movie).

(13c) Making the movie took Allen four years.

(13d) *Allen was taken (by making the movie) four years.

(14a) The movie took four years to make.

(14b) *Four years were taken (by the movie) to make.

(14c) The movie took Allen four years to make.

(14d) *Allen was taken (by the movie) four years to make.

What's happened here is that the Gremlins version of the second conjunct introduced an entirely new construction, not in the original (again, without comment or explanation). On top of that, the construction totally fails to fit the Gremlins characterization of active clauses, and indeed suppresses any mention of the maker(s) of the movie, just the way an agentless passive does. Goodness knows what readers are supposed to make of all this for practical purposes.

Now I'm not claiming that there's something wrong with the second conjunct of (II). In fact, I think it's pretty good. There are several variants or expansions of it that might also do:

(15b) ... it took four years for Y to make the movie. [with mention of the maker(s)]

(15c) ... it took four years to make the movie of it. [with explicit reference to the book]

(15d) ... it took four years for Y to make the movie of it. [combo of (b) and (c)]

(16a) ... making the movie took four years.

(16b) ... making the movie took Y four years.

(16c) ... making the movie of it took four years.

(16d) ... making the movie of it took Y four years.

No doubt you can imagine still other possibilities. What's good about all of these is that they bring out the two relevant contrasts, between the movie and the book and between four years and four months.

The problem with (II) is its first conjunct, specifically the subject of this clause. Version (II) treats the writer of the book as topical, and that's possible (if so, then (II) conveys a topic shift, away from the writer of the book to the book itself, in contrast to the movie), but it's likely, especially when the sentence is viewed out of context, that the book is topical, in which case we want the book to be the subject of this clause -- that is, we want a passive. The book's writer can then be downgraded in its discourse status (by being mentioned in a by-phrase), or you can suppress mention of the writer entirely, depending on your wider aims in the discourse:

(or with any of the other variants for the second clause, or with one of the constructions in (14) in the first clause). And if you want to treat X as topical, then there are further possibilities, with active verbs in both clauses, for instance:

To sum up: the Gremlins treatment of the passive is appalling, but in detailing just what is appalling about it I've tried to bring out some important points. What's especially disheartening, though, is that The Elements of Style (right back to the Strunk 1918 original) -- cited approvingly in the Gremlins reading list, by the way -- gets some of this right. In particular, Strunk appreciates the significance of topicality in choosing between active and passive. Here's his summary:

(Note the nominal of making a particular word... instead of the verbal to make a particular word... and the passive is to be used instead of the shorter and active to use. Strunk wasn't very good at following his own advice.)

Now we get to Virginia Tufte. Tufte just assumes her readers are acquainted with the concepts and terminology of traditional grammar; her aim is to show you what you can do with the resources of English. The section on "the passive verb" begins with the usual semantic characterization:

Oh dear. But then she jumps right into a discussion of discourse organization:

She also notes that "for good or ill" the passive allows you to omit this noun phrase entirely.

More generally,

There is no hymn to the energetic activity of the active, no castigation of the boring submissiveness of the passive. It's all about what you can do with the two voices.

If you don't know how to recognize a passive (at least in the easy cases), then you'll need some background before you can tackle Tufte. Don't, however, try to get it from Gremlins.

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

VPE on the edge

Our very own John McWhorter wrote the following yesterday:

No doubt John knew just what he was doing here: producing an instance of so-called Verb Phrase Ellipsis (VPE) -- in "one is ___" -- where the missing material is to be understood as "writing a whole paper on it" (a present participle VP), even though the antecedent is "write a whole paper on it" (a base-form VP). I think many readers would have a moment (up to a few centiseconds, maybe) of pause while they worked that one out, and possibly they would have had a small spike in their P600 ERP responses (but nothing special for N400), indicating that they were noting a syntactic surprise. He was playing with us, making us do a little bit of interpretive work and, maybe, giving us some enjoyment in the process.

[Added 12/29/06: Several readers note that part of the surprise effect is in the shift from truly generic one to the pseudo-generic one that refers to the speaker.]

Two things here: what counts as a legitimate VPE (some things are definitely on the edge); and how to draw the line between creative language use that stretches the boundaries of grammar a bit and plain unacceptability (again, there are things on the edge).

Background about VPE: this is an English construction in which the complement of an auxiliary verb (a modal, BE, or perfect HAVE, plus a few other things for some speakers) or infinitival TO is omitted:

(2) I'm not going, but Dmitri is ___.

(3) I was attacked by the wolves, but Dmitri wasn't ___.

(4) I'll be unhappy, and Dmitri will be ___, too.

(5) I've finished my work, and Dmitri has ___, too.

(6) I don't want to eat the sashimi, but Dmitri wants to ___.

(The "remainder" elements are bold-faced here, and the missing complements are indicated by underscores.)

Though the construction is usually known as Verb Phrase Ellipsis (sometimes Verb Phrase Deletion), the omitted phrase is not always a VP. In (4), it's an AdjP. "VPE" isn't a bad name, but it doesn't tell you everything. The slogan is: Labels Are Not Definitions.

VPE requires a linguistic antecedent -- it's not enough that the appropriate verbal semantics be "in the air" -- but it doesn't require that the omitted complement match the antecedent perfectly. Infinitival TO as remainder will have an omitted bare-form VP, but the antecedent can have a different non-finite form:

or a finite form:

(The head verbs in the antecedent phrases are italicized here.)

Various other mismatches between the omitted phrase and its antecedent are possible. But some mismatches are edgy, and John McWhorter's -- present participial omitted VP, base-form antecedent VP -- is one of them. Here's a parallel example that I copied into a file because I lingered over it for a slice of a moment:

It's not hard to collect even more extreme mismatches, which some people judge to be acceptable, while others do not. Here's one Ron Hardin reported on in the newsgroup sci.lang on 9/28/06, from an NYT editorial:

Here the antecedent is passive, while the omitted VP is active ("try and convict those men").

Even further out -- well over the line, for me -- is this one:

Here the antecedent VP isn't explicit, but is suggested by the prepositional phrase "with a sulfa side chain": "have a sulfa side chain".

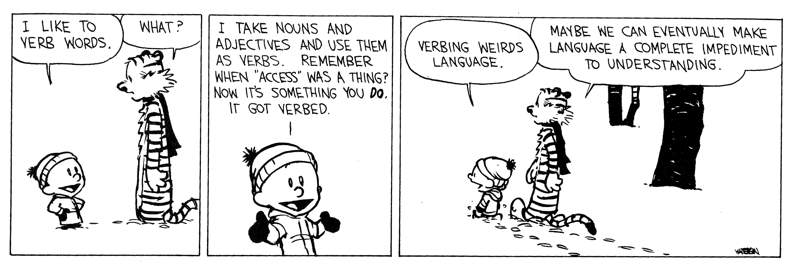

My response to most of the imperfectly matching VPE examples, however, is that they are either straightforwardly acceptable (and so escape notice unless I'm specifically looking for such examples) or edgy in their syntax but interpretable -- much like novel verbings:

I really gangbustered to get it [the project report] out. (Overheard by Tyler Schnoebelen, March 2005)

Updating my web site to reflect new movie scripts, DVDs and musical score CDs that the studios have freebied me with ... (Ken Rudolph on soc.motss, February 2002)

(plus an enormous number based on proper names: the verbs Bork, Winona, Martha Stewart, (James) Frey, Wal-Mart, etc.)

Novel verbings are all over the place; people invent them all the time. Some critics object to those that have become widespread, like access and dialogue, but as far as I can tell the objections are really about the tone of these words (they are administrativese or pretentious, or in the case of consequence 'punish', euphemistic) rather than about morphological conversion itself. Otherwise, verbings are just part of the artistry of everyday language, and like other artistry, require a bit of work by the audience. They frustrate the audience's expectation for a split second; resolving the surprise can then provide pleasure. (For the record, I found John McWhorter's VPE sentence satisfying.)

But: writing advice routinely counsels against surprising your audience, against making your readers work. Interpretation is supposed to be seamless and smooth. It is, of course, only too easy to find sentences that require far too much work, even in their context; we comment here fairly often on various sorts of ineptness that make the reader's task onerous. Still, there ought to be room for a certain amount of artistry in all sorts of writing; people shouldn't have to wait until they get their Fine Writer Certificate to play with some of the available effects.

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

On the trail of "the new black" (and "the navy blue")

In our occasional roundups of those phrasal formulae we call snowclones, one of the most fertile templates has been "X is the new Y" — most recently discussed in three posts by Arnold Zwicky (1, 2, 3), but extending back to the early days of snowclonology (1, 2, 3, 4; see also this pioneering post by Glen Whitman). The Wikipedia page on snowclones even gives "X is the new Y" as its very first example. Wikipedians and some other observers have suggested that the original model for this snowclone is the supposed fashion-industry motto, "Pink is the new black," which first got extended to "X is the new black" before becoming abstracted even further as "...the new Y."

So, to whom can we attribute what Arnold Zwicky calls "the ur-New-Y expression"? Turning again to Wikipedia:

The phrase is commonly attributed to Gloria Vanderbilt, who upon visiting India in the 1960s noted the prevalence of pink in the native garb. She declared that "Pink is the new black", meaning that the color pink seemed to be the foundation of the attire there, much like black was the base color of most ensembles in New York.

The attribution of "pink is the new black" to Vanderbilt has been dutifully repeated in a number of places in recent months, including The Ottawa Citizen, The Taipei Times, kottke.org, Eric Zorn's Chicago Tribune blog, and right here on Language Log. There's only one small problem with the Vanderbilt attribution: it's completely unsubstantiated. It looks like Diana Vreeland should get the credit instead, though she didn't quite say "pink is the new black" either.

[Update, 12/29: The Wikipedia entry for "the new black" has already been revised to give Vreeland credit rather than Vanderbilt. The uncorrected version is archived here.]

The attribution to Vreeland first popped up on the Wikipedia page for "the new black" in a revision on Sep. 13, 2005 by "DropDeadGorgias." The source for this information is uncredited, but some more digging finds that "DropDeadGorgias" wrote a post on Plastic.com on Jan. 22, 2004 mentioning a Guardian headline, "Gay is the new black." (The post was about early reports of the filming of Brokeback Mountain.) In the comments section, "HWheel" offered this explanation for the origin of "the new black":

In the swinging '60's, Gloria Vanderbilt visited India. Everybody was wearing wild colors, but there was lots of pink. She said "Pink is the new black." It's now a fashion cliche: "_________ is the new black," which changes every year.

I got this from the one-woman play, "Full Gallop," which was the wit and spirit of Ms. Vanderbilt.

So it looks like "DropDeadGorgias" took the commenter's word for it and amended the Wikipedia page for "the new black" to say that the expression is "commonly attributed to Gloria Vanderbilt." Unfortunately, this bit of information fails Wikipedia's usual standards of verifiability. Nobody else attributes "the new black" to Vanderbilt, except for people relying on the faulty Wikipedia entry.

A little more research zeroes in on the source of the misinformation. That one-woman play referred to by the Plastic.com commenter, "Full Gallop," is not about Gloria Vanderbilt — it's actually about Diana Vreeland. It's easy to see how one could get the two women confused: they're both chic fashion divas and high-society types with last names beginning with V. Vreeland, however, is the one who evidently deserves a place in the annals of snowclonology.

So what did Vreeland actually say? Turns out she didn't call pink "the new black," or even "the black of India," but rather "the navy blue of India." (Note also that calling pink "the navy blue of India" is actually more akin to snowclones of the "X is the Y of Z" model.) Vreeland's original wording is preserved in the script of "Full Gallop" by Mark Hampton and Mary Louise Wilson (published in 1997 but first performed in 1995 with Wilson in the role of Vreeland):

Actually, pale-pink salmon is the only color I cannot abide.

Although, naturally, I adore PINK. I love the pale Persian pinks of the little carnations of Provence, and Schiaparelli's pink, the pink of the Incas.

And, though it's so vieux jeu I can hardly bear to repeat it, pink is the navy blue of India.

This passage, like others in the script, is taken verbatim from Vreeland's 1984 memoirs, D.V. (p. 106 of the 1997 Da Capo Press edition, which incidentally has a foreword by Mary Louise Wilson). By that time, near the end of her life, she seemed quite bored with her famous catchphrase, considering it so vieux jeu (lit. 'old game') that she could barely stand repeating it. Indeed, a Nov. 28, 1980 profile of Vreeland in the Washington Post referred to "Pink is the navy blue of India" as "her most frequently quoted statement."

The quote had, in fact, been traveling with Vreeland ever since she burst into the public eye as the editor of Vogue in early 1962. In March of that year, Carrie Donovan wrote a long New York Times profile of Vreeland that included this anecdote:

A designer tells of the time he showed Mrs. Vreeland a swatch of bright pink silk of Eastern influence.

"I ADORE that pink!" she exclaimed. "It's the navy blue of India."

("Diana Vreeland, Dynamic Fashion Figure, Joins Vogue," New York Times, Mar. 28, 1962, p. 30)

In her 2002 biography Diana Vreeland, Eleanor Dwight identifies Donald Brooks as the designer who shared the story with the reporter. (Vogue photographer Norman Parkinson also recalls Vreeland's saying the line to him, as recounted in his 1983 book Fifty Years of Style and Fashion, reviewed here.) There must have been something particularly striking about Vreeland's bold formulation, since it would often be repeated in profiles of her — as in "The Vreeland Vogue," a Time Magazine piece from May 10, 1963.

Some claim that Vreeland's comment was inspired by a trip to India (as the Wikipedia entry claims was true of Vanderbilt), but I haven't found any evidence of this. I doubt this was the case, since in D.V. she writes that as a fashion editor she herself didn't travel, instead living vicariously through international fashion shoots: "I couldn't take off for a few weeks to see, say, a bit of India. But I could send groups of photographers, editors, and models, and they'd be there the next day." So I'd imagine that she came to the conclusion that "pink is the navy blue of India" based on one of these shoots that she arranged from the comfort of her New York office.

But when did "the new black" enter the picture? I have yet to find any usage before the 1980s, when various colors were anointed "the new black":

Colors are slated to be somber and muted, say most of the designers who previewed their collections for Fashion83. For example, Ferre says gray is the new black. (Los Angeles Times, Mar. 4, 1983, p. V6)

"There is a tremendous range to the color brown," says [textile and color specialist Elaine] Flowers, who expects brown to look updated because of the way it is paired with other colors, and used in varied textures. "It is the new black." (Washington Post, Mar. 15, 1984, p. D9)

Navy is the new black in Paris; in London and Milan, brown is the preferred alternative. (Washington Post, Apr. 3, 1984, p. C6)

"We're very strongly navy for the season," he [sc. merchandising agent Joseph Martinez] said. "Navy is the new black." (Los Angeles Times, Oct. 26, 1984, p. IV15)

Nearly 4,000 fashion professionals filled the New York Hilton's ballroom for two runway shows spotlighting fall trends: trumpet skirts, swing dresses, styles the moderator said were ''for the woman whose bank account is equal to her self-assurance,'' belts (''the accessory of the year''), velvet, gray (''the new black''), boots and big coats. (New York Times, May 27, 1986, p. C12)

Diana Vreeland is not mentioned in any of these early cites, and her use of navy blue as a standard fashion color had been replaced by black (thanks to Donna Karan and other designers of the day). It's hard to know exactly what influence Vreeland had on the "new black" pronouncements of the '80s, but perhaps for fashionistas of the era the old line about pink being "the navy blue of India" was such common knowledge that it was easy to mold into the "X is the new black" template. Or perhaps there are still some missing steps between the Vreelandism and the later snowclones. Either way, it doesn't look like Gloria Vanderbilt had anything to do with it.

[Update: Barry Popik has tracked down an intermediary step on the way to "the new black" of the '80s — "the new neutral":

Colors are the new neutrals. Find a color you like and wear it with everything. (New York Times, Sep. 16, 1979, p. NJ16)

Pearl gray is the new neutral, navy and black are everywhere, alone or with anything. (Chicago Tribune, Nov. 12, 1979, p. B3)

Lila Schneider, another New York designer, said, "Pink is the new neutral — a change from the stark white of the last few years." (Chicago Tribune, Oct. 19, 1980, p. 13-1)

No one knew how to interpret all this color experimentation until one New York observer finally blurted: "It looks like red is the new neutral." (Toronto Globe & Mail, Nov. 24, 1981, p. F6) ]

Onomastic malice

I don't have a clue about what my parents were thinking when they gave me my middle name, Wellington. Since childhood, I've tried to bury it by using only an initial, W, and I've been even more diligent now that W has taken on a, well, more pejorative meaning. But think for a minute about the public relations problem Barack Obama has these days with his own middle name, Hussein. Or, for that matter, with his family name, Obama. And Barack may not be so helpful either. David Wallis (note the omission of his middle name, Robin, or even his initial) writes about this in a recent Slate article.

Wellington is some sort of national hero in England, at least, but not for a working class kid growing up in industrial northeastern Ohio, where it signified only uppity stuffiness and pretense. It even served as a mocking insult when I missed a crucial shot in an important high school basketball game and my classmates in the stands shouted out, "Wellington," to show their disapproval--one of those memories that I want to erase but can't quite purge.

Already Republican strategist Ed Rogers and right wing screeder Rush Limbaugh have started a political and bigoted onomastic attack on Obama. So far, at least, Obama has tried to use only his first and last names, not even suggesting that there is an H lurking there some place. But middle initials are said to sound presidential, like John F. Kennedy, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Gerald R. Ford, or Richard M. Nixon, and I wonder if Obama eventually will need to admit that he's forever stuck with an H there. Like my (sigh) W.

Not-so-worrisome details

The BBC may still be peddling its nonsense about cow dialects, but at least one comic strip character has rightly decided not to worry about this factitious factoid.

Here's today's "Sylvia":

Good instincts, Woman Who Worries About Everything!

(Hat tip Joel Berson.)

Factoids of the Year

Today the BBC News "Magazine Monitor" posted "100 things we didn't know last year", introduced like this:

Each week, the Magazine chronicles interesting and sometimes downright unexpected facts from the news, through its strand 10 things we didn't know last week. Here, to round off the year, are some of the best from the past 12 months.

One of the featured items was very familiar:

45. Cows can have regional accents, says a professor of phonetics, after studying cattle in Somerset

Truly, they have no shame -- see "It's always silly season in the (BBC) science section" (8/26/2006) for the hilarious details.

One of the "10 things" in this week's "strand" will also be familiar to our readers:

1. Just 20 words make up a third of teenagers' everyday speech.

What fraction of the other 100 "interesting and ... downright unexpected facts" do you suppose are equally bogus? I'm not sure, but I'll bet at least that the presentation by BBC News is careless and misleading. Let's check another factoid with linguistic connections:

57. The word "time" is the most common noun in the English language, according to the latest Oxford dictionary.

This is a reference to a news item from June 22, "The popularity of 'time' unveiled", which is basically a re-write of an item from the "English Uncovered" supplement to the Concise Oxford Dictionary. "The hundred commonest English words" was posted on the AskOxford.com site on January 6, 2006, so there was plenty of time for research.

And the BBC got the main point right: the commonest noun in the BBC's billion-word corpus was indeed listed as time. But the story does manage to botch the background reasoning:

OUP project manager Angus Stevenson said much of the frequency of the use of words such as "time" and "man" could be put down to the English love of phrases, such as "time waits for no man."

I doubt very much that Angus Stevenson uttered any such preposterous violation of common sense. A quick Google search suggests that "time waits for no man" contributes only 67,800 hits towards the 2.23 billion pages containing time, and the 1.04 billion pages containing man. What the "English Uncovered" supplement actually says about this is:

Another reason for a word's high position on the list is that it forms part of many common phrases: most of the frequency of time, for example, comes from adverbial phrases like on time, in time, last time, next time, this time, etc.

Indeed, this version of the assertion is intuitively plausible, and Google counts for the listed phrases -- 59.9m, 192m, 45.4m, 71.7m, 267m respectively -- confirm the intuition. We're not asking for higher mathematics here -- just a bit of common sense, basic logic, and elementary care for the facts.

Here's a recent fact that I didn't know ("BBC loses license fee battle", 12/27/2006):

In what amounts to a major blow to the credibility of BBC director general Mark Thompson, the government has reportedly decided to go ahead with a far lower license fee settlement than called for by the BBC.

According to sources close to the settlement, Treasury Secretary Gordon Brown has settled on a 3% increase in the BBC's £3.3 billion ($6.5 billion) per year license fee in 2007, followed by an increase of 2% per year over the following three years.

The figures fall far short of the BBC's call for a 5.7% increase each year through 2012, a figure it said would take account the rate of inflation, currently running at 3.9%.

The news was broken by Channel 4 News and widely picked up by news organizations here.

When the BBC made its original license fee bid at the start of the year, it called for a license fee hike amounting to 6.4% a year for seven years. This was later revised downward to 5.7% after the government's independent auditors rejected the BBC's own financial analysis and cost projections.

I don't think that very much of that $6.5 billion per year goes to BBC News. But still, you'd think they spoke one of those languages without a word for accountability.

Like, a Christmas gift card

The Zits strip for Christmas Eve offered five gift cards a teenage boy can give his parents. All five are gifts of "communication", in a broad sense, and four of the five are specifically about language:

My favorite, of course, is the one that gets central billing in the

cartoon, about the word like.

I like that one [yes, that was intentional] because I'm part of the

Stanford ALL Project -- initiated by John Rickford and also involving

Isa Buchstaller, Elizabeth Traugott, Tom Wasow, and me, plus a

supporting cast of students, both undergraduate and graduate -- which

looks at innovative uses of all

(in particular, intensifier all

and quotative all) and ends

up looking at quotative like

as well:

I'm like "Yeah," and she's all "no" [From

the song of the same name by the Mr. T Experience]

(Look for Rickford, Buchstaller, Wasow, and Zwicky on all, to appear soon in American Speech. Manuscript

available here.)

Now, the thing about like

is that, even if you exclude the verb like,

it has so very many uses -- at least: as a preposition, a subordinator,

a discourse particle, a quotative, and a sentence-introducing element,

in an ironic assertional use:

Like I care about what you think.

'I don't care what you think'

And there are subtypes of the prepositional, subordinator, and

discourse particle uses. We've looked at a number of these, in an

unsystematic way, here on Language Log. Back in May 2005, Mark

Liberman assembled a list

of postings up to that point, with pointers to another blog and to

Muffy Siegel's 2002 paper on like

as a discourse particle (which includes references to the earlier

literature on the subject).

In any case, teenagers have been fond of discourse-particle uses of like for quite some time, at least

50 years; some people now in their 50s and 60s still use like this way. Meanwhile,

quotative like has risen in

25 or 30 years to become the dominant quotative in the speech of young

people (and some older speakers use it too). The result is that

some young people are indeed heavy users of like in functions that some of

their elders do not use it in. And many of these older speakers

are annoyed as hell about that.

This strongly negative response deserves some attention and

analysis. Here I'm just going to open up the issues a bit.

When people complain to me about discourse-particle and quotative like,

I ask them why they dislike it so, and they usually say that kids are

just sprinkling a meaningless word (discourse-particle like) all over their sentences and

are inexplicably choosing to use a preposition (quotative (be) like) instead of the perfectly good

verb say. They

characterize these uses as "bad habits"; they are very resistant to the

idea that people who use like

as a discourse particle or quotative are actually DOING THINGS

by their linguistic choices (though the functions of these choices are

what linguists have mostly been interested in); and they are offended

by teenagers' rejection of older standard usages in favor of

innovations. That is, they make no attempt to figure out what

people who use a somewhat different variety from their own are

conveying (they are uncooperative in their interpretation of other

people's speech), and they refuse permission to other people to have

varieties of their own (they demand conformity).

Uncooperativeness and demands for conformity attend responses to

other inter-group linguistic differences, of course, especially when

the groups differ socially, in power or prestige. I have met

people who simply REFUSE to understand "double

negation" (I didn't see no dogs

'I didn't see any dogs') in non-standard varieties, for example.

But young people seem to suffer especially from these responses.

No doubt that's because they are, after all, OUR

children (for some sense of our)

and we are distressed that they refuse to be just like us.

Note that discourse-particle and quotative like have both linguistic value

(they can be used to convey nuances of meaning) and social value

(they're part of the way personas and social-group memberships are

projected). I'm not denying that there are fashions in these

things; a major part of the Stanford ALL Project's recent work, in

fact, has treated changes over time (some of them huge) in the details

of the way people use all and

its competitors. When I talk to those who object so strongly to

"innovative" uses of like, I

try to hit both the linguistic and the social points: the kids are

doing things with these usages, and they're also following fashion (and

there's nothing intrinsically wrong with that, especially if you're

15). And: nobody is saying that YOU should be

talking that way.

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

A little more of The New Y

I don't intend to post new sightings of the snowclone The New Y as they come in -- there are just too many of them -- but I've recently come across two examples that strike me as of more than routine interest.

Meanwhile, as New Year's Day approaches, I've been hoping to unearth instances of "X is the new year": the decade is the new year, decades are the new years, the month is the new year, months are the new years, etc. No luck so far.

New sighting 1: "Pink is the new gold." This cleverness from Peggy Orenstein in a New York Times Magazine piece "What's wrong with Cinderella?" (12/24/06, p. 36). The story is about the "princess" trend for little girls, with everything in the color pink, a trend that is making huge profits (the gold) for Disney, Mattel, and others. This one echoes the ur-New-Y expression "Pink is the new black" in having pink as the subject and (what can be used as) a color word, gold, in the predicate, while punning on that word. Anyone unfamiliar with the snowclone would probably have a lot of trouble interpreting the sentence.

New sighting 2: "Doubt is the new religion, but does doubt doubt itself?" In a letter to the New York Times (12/26/06, p. A26) from Peter McFadden, writing about a recent upsurge in commentary critical of religious belief. This one is interesting because it can be read literally, parallel to "Doubt is the new trend" and understood as conveying 'Doubt is a new religion', or as an instance of the snowclone, conveying something stronger, roughly 'Doubt has replaced religion'. My first guess was that McFadden intended the latter, but then I'm disposed to see snowclones everywhere.

zwicky at-sign csli period stanford period edu

An apology to our readers

This morning, I was suddenly seized by the compulsion to correct an injustice. Geoff Pullum and I were the perpetrators, and our motives were pure. The victim was the BBC News organization, which amply deserved what we did, and worse. But an injustice it was nonetheless: we used an unfair and misleading argument.

The BBC's reporters and editors might be lazy and credulous, scientifically illiterate, bereft of common sense, dishonest, and given to promoting dubious products, but they deserve to be confronted with sound arguments based on solid facts. (A bit of humor is OK as well -- they're an easy target --but that's not the point here.) More important, our readers expect and deserve sound arguments and solid facts from us. But when Geoff and I took the BBC to task for their 12/12/2006 story "UK's Vicky Pollards 'left behind'", we used an invalid argument. It may have cited genuine facts and reasoned to a correct conclusion, but a step in between was, well, fudged.

I felt a little bad about it, but the general outlines of the argument were right, and I didn't have time to do a better job. My conscience has been nagging at me, though, and so this morning I'm going to set the record straight. Or at least, I'll set it as straight as I can. I'm handicapped by the fact that the the particular batch of nonsense that the BBC was serving up on December 12 was based on their misinterpretation of an unpublished, proprietary report, prepared by Tony McEnery for the conglomerate Tesco.

So I can't do the calculations that would allow a fair version of the argument. I'll do what I can for now, and I'll ask Tony if he'll do the corresponding calculations on the data that's unavailable to me. In any case, there's some conceptual value in the discussion, I think, even if we never learn the whole truth about this particular case.

The thing that set it off was the second sentence of the BBC story:

Britain's teenagers risk becoming a nation of "Vicky Pollards" held back by poor verbal skills, research suggests.

And like the Little Britain character the top 20 words used, including yeah, no, but and like, account for around a third of all words, the study says. [emphasis added]

Arnold Zwicky, who still likes to think of the BBC as run by sensible and honest people, commented in passing ("Eggcorn alarm from 2004", 12/14/2006):

[T]his could merely be a report on the frequency of the most frequent words in English, in general. If you look at the Brown Corpus word frequencies and add up the corpus percentages for the top 20 words (listed below), they account for 31% of the words in the corpus. But that would be ridiculous, and it wouldn't distinguish teenagers from the rest of us, so what would be the point?

The point, I figured, was to pander to their readers' stereotype of lexically impoverished teens. To help readers understand this, I made the same general argument that Arnold did, at greater length and with some different numbers ("Britain's scientists risk becoming hypocritical laughing-stocks, research suggests" 12/16/2006):

The Zipf's-law distribution of words, whether in speech or in writing, whether produced by teens or the elderly or anyone in between, means that the commonest few words will account for a substantial fraction of the total number of word-uses. And in modern English, the fraction accounted for by the commonest 20 orthographical word-forms is in the range of 25-40%, with the 33% claimed for the British teens being towards the low side of the observed range.

For example, in the Switchboard corpus -- about 3 million words of conversational English collected from mostly middle-aged Americans in 1990-91 -- the top 20 words account for 38% of all word-uses. In the Brown corpus, about a million words of all sorts of English texts collected in 1960, the top 20 words account for 32.5% of all word-uses. In a collection of around 120 million words from the Wall Street Journal in the years around 1990, the commonest 20 words account for 27.5% of all word-uses.

I should have pointed out that the exact percentage will depend not only on the word-usage patterns of the material examined, but also on

- the details of the text processing (the treatment of digit strings and upper case letters makes a big difference, as does the frequency of typographical errors);

- the size of the corpus -- larger collections will generally yield smaller numbers;

- the topical diversity of the corpus -- new topics bring new words.

(The first factor, by the way, explains why Arnold got 31% and I got 32.5% for the Brown corpus.)

Without controlling carefully for those factors, citing the percent of all words accounted for by the 20 commonest words is almost entirely meaningless. That was the BBC's second mistake. Their first mistake was to imply that a result like 33% is in itself indicative of an impoverished vocabulary.

And in my desire to demonstrate in a punchy way the stupidity of this implication, I did something unfair -- I cited the comparable proportion for the 1190-word biographical sketch on Tony McEnery's web site:

And in Tony McEnery's autobiographical sketch, the commonest 20 words account for 426 of 1190 word tokens, or 35.8% . . .

In fact, Tony used 521 distinct words in composing his 1190-word "Abstract of a bad autobiography"; and it only takes the 16 commonest ones to account for a third of what he wrote. News flash: "COMPUTATIONAL LINGUIST uses just 16 words for a third of everything he says." Does this mean that Tony is in even more dire need of vocabulary improvement than Britain's teens are?

Now, I knew perfectly well that this was an unfair comparison, since the BBC's number was derived by unknown text-processing methods applied to unknown volumes of text on an unknown range of topics. I considered going into all of that -- but decided not to, partly for lack of time, and partly because it weakened the point. So I decided to put forward my own little experimental control instead:

In comparison, the first chapter of Huckleberry Finn amounts to 1435 words, of which 439 are distinct -- so that Tony displayed his vocabulary at a substantially faster rate than Huck did. And Huck's commonest 20 words account for 587 of his first 1435 word-uses, or 40.9%. So Tony beats Huck, by a substantial margin, on both of the measures cited in the BBC story. (And just the 12 commonest words account for a third of Huck's first chapter: and, I, the, a, was, to it, she, me, that, in, and all.) We'll leave it for history to decide whose autobiography is communicatively more effective.

This evened the playing field, since Huck gets a higher 20-word proportion than Tony, for the same text-processing methods applied to a slightly larger text. And I thought it was a good way of underlining the point that Geoff made back on Dec. 8 ("Vocabulary size and penis length"):

Precision, richness, and eloquence don't spring from dictionary page count. They're a function not of how well you've been endowed by lexicographical history but of how well you use what you've got. People don't seem to understand that vocabulary-size counting is to language as penis-length measurement is to sexiness.

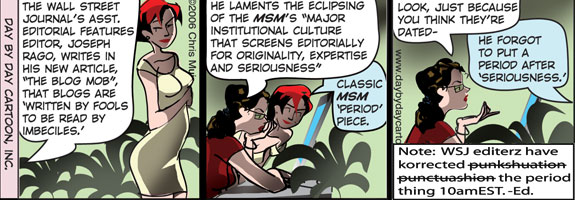

Geoff Pullum was then inspired to give the BBC a dose of their own medicine ("Only 20 words for a third of what they say: a replication"), and observed that in the 402-word "Vicky Pollard" story itself, the top 20 words account for 36% of all words used -- more than the 33% attributed to Britain's teens.

This is a great rhetorical move -- the BBC's collective face would be red, if they weren't too busy misleading their readers to pay attention to criticism. But at this point, in fact, Geoff and I may have misled our own readers.

I'll illustrate the problem with another little experiment.

A few days ago, I harvested a couple of million words of news text from the BBC's web site. I then wrote some little programs to pull the actual news text out of the html mark-up and other irrelevant stuff, to divide the text into words (splitting at hyphens and splitting off 's, but otherwise leaving words intact), removing punctuation, digits and other non-alphabetic material, and mapping everything to lower case. As luck would have it, the first sentence, 23 words long, happens to involve exactly 20 different words after processing by this method:

the

father

of

one

of

the

five

prostitutes

found

murdered

in

suffolk

has

appealed

for

the

public

to

help

police

catch

her

killer

This of course means that the 20 commonest word types -- all the words that there are -- account for 100% of the word tokens in the sample so far. If we add the second sentence, 19 additional word tokens for 42 in all, we find that there are now 36 different word types, and the 20 commonest word types occur 26 times, thus covering 26/36 = 72% of the words used. The third sentence adds 24 additional word tokens, for 66 in all; at this point, there 53 different word types, and the 20 commonest ones cover 33/66 = 50% of the words used. After four sentences, the 20 commonest words cover 35/75 = 47% of the words used; after five sentences, 48/105 = 46%.

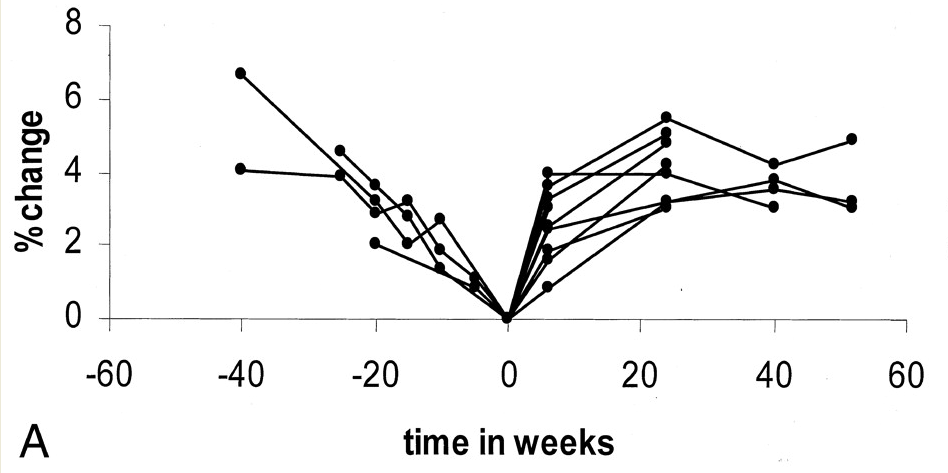

By now you're getting the picture -- 100%, 72%, 50%, 47%, 46% ... As we look at more and more text, the proportion of the word tokens covered by the 20 commonest word types is falling, though more and more gradually.

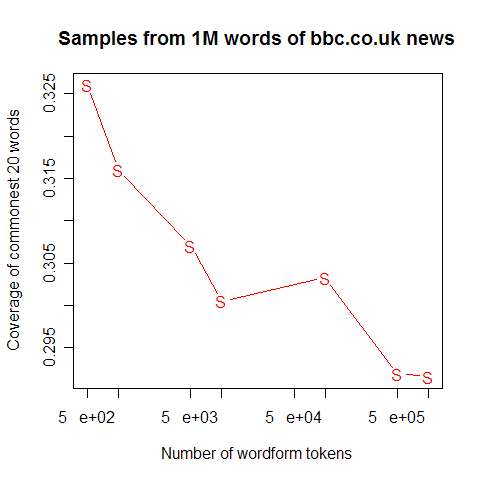

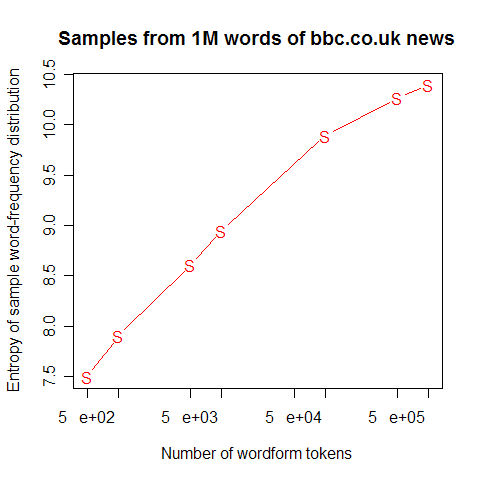

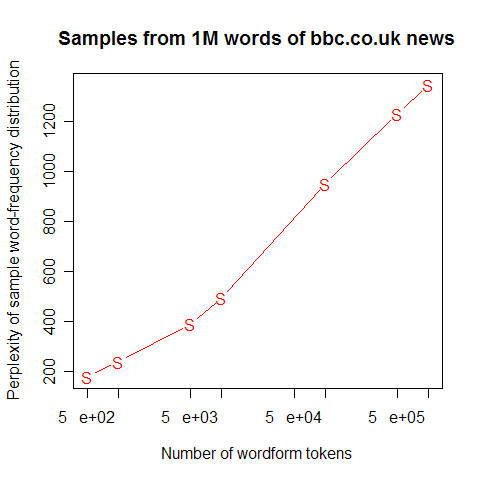

What happens as we increase the size of the sample? Well, the proportion continues to fall in the same sort of pattern. Here's a plot showing the values from 500, 1k, 5k, 10k, 100k, 500k and 1m words in this same sample of BBC text: